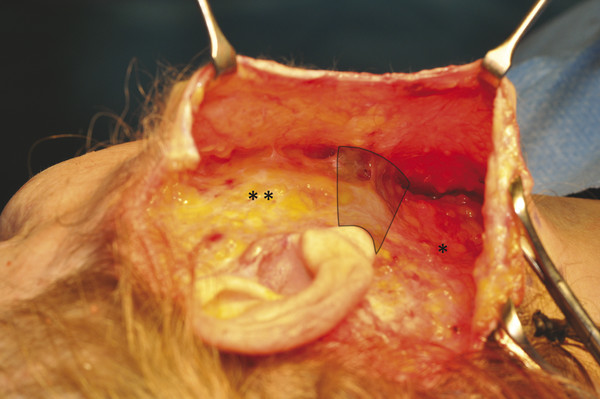

Historical Perspective Historically, simultaneous resurfacing and surgical undermining in rhytidectomy was advised against because of reported skin necrosis seen after treatments with deep chemical peels.3,4,5 Over the past few decades, isolated use of CO2 and various lasers for full-face ablative resurfacing has shown beneficial effects with wide acceptance in aesthetic practices. More recently with fractional ablative resurfacing platforms, patients have enjoyed skin rejuvenation with less downtime than traditional ablative resurfacing, and potentially fewer risks.6,7,8 Further details into the history, mechanisms, and the benefits of various laser therapies and systems are discussed throughout other chapters within this text. Due to advances in resurfacing platforms, as well as improvements and better understanding of rhytidectomy techniques, the outcomes of simultaneous flap elevation and skin exfoliation have shown excellent results without an increased risk to the undermined skin flaps.1,2 Different areas of the face often require varying levels of laser treatment, whether or not a simultaneous procedure is performed. The pertinent technical details are outlined to guide those physicians with a similar patient population wishing to implement this combined modality in their practice. Evaluation of the patient begins with a complete medical history with special attention to, and documentation of, medication use, skin sensitivities, and allergy history. Patients should be screened for conditions that may increase their risk of complications, or diseases that might prolong the postoperative healing time. These conditions include diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, collagen vascular diseases, and some autoimmune disorders that could compromise the microvasculature of the tissues.9 Another segment of patients who are very important to identify include patients who are actively smoking. Smoking greatly compromises the vascularity of the skin flap, increasing the likelihood of postoperative necrosis and sloughing with rhytidectomy alone. Therefore, the authors deem active tobacco use as a contraindication to simultaneous rhytidectomy with laser resurfacing. Pertinent medications include previous or current use of powerful retinoids such as isotretinoin (Accutane, Roche Pharmaceutical, Basel, Switzerland) that can lead to increased scarring in patients undergoing facial resurfacing.10,11 This medication can blunt regrowth of epithelial appendages that are essential for postoperative re-epithelialization.11 The authors recommend waiting 6 to 12 months after use of isotretinoin before undergoing any type of ablative resurfacing procedure. Patients with a history of head and neck radiation should also be approached cautiously when resurfacing because this subset of patients can have microvascular compromise even more severe than that of smokers. Radiation can decrease the blood supply as well as the number of pilosebaceous subunits, further delaying healing and potentially increasing the risk of scarring. Individuals who have active autoimmune diseases such as scleroderma, lupus, or Sjögren syndrome similarly carry a higher risk of skin flap compromise, and the decision to operate on these patients should be considered a relative contraindication. Discussions with a patient’s rheumatologist should be initiated given the poor and unpredictable healing that can occur, as well as the risks of reactive cutaneous flares that can occur in these disease processes with laser treatment. As always in the setting of aesthetic surgery, the motivations of the patient are of paramount importance. The surgeon should ensure the patient has realistic expectations and a firm understanding of the potential complications. This allows the patient and surgeon to choose the appropriate treatment and ensures that the patient understands the associated risks of combined modality treatment. The surgeon should not hesitate to defer treatment, and then schedule a second consultation to explore the patients’ motives and ensure their expectations are realistic and align with the proposed intervention. Considerations for psychological consultation should be raised in a patient who continues to have unrealistic expectations.9 Classification of the patient’s skin type is essential before proceeding with a resurfacing procedure. The Fitzpatrick classification uses the skin’s response to sun exposure and the person’s baseline skin color as a means of categorizing patients (▶ Table 5.1).12 Patients with darker complexions undergoing deep resurfacing procedures carry an increased risk of pigmentary changes, and therefore the ideal candidate for deep resurfacing would be a person of Celtic or northern European descent with Fitzpatrick skin type I or II.13 Glogau further classifies the skin according to the amount of clinical photodamage (▶ Table 10.1), which guides the physician in choosing the appropriate level of resurfacing.14 Most patients necessitating and undergoing CO2 or deep Er:YAG ablative procedures would fall into the higher groups, such as III or IV (▶ Fig. 10.1). Group I No wrinkles No keratoses 20s to late 30s Group II Wrinkles in motion Keratosis palpable but not visible Late 30s to 40s Group III Wrinkles at rest Obvious dyschromias, telangiectasias, and keratoses 50s and older Group IV Only wrinkles Actinic keratoses with or without skin cancers 70s and older (Adapted with permission from Glogau RG, Matarasso SL. Chemical face peeling: patient and peeling agent selection. Facial Plast Surg 1995; 11: 1–8.) Fig. 10.1 (a) A 69-year-old woman with preoperative facial aging and severe photodamage. (b) Results 12 months postoperative following simultaneous rhytidectomy, full-face laser resurfacing, endoscopic forehead lift, and upper and lower eyelid blepharoplasty. Preoperative topical therapies are used by most treating physicians with several preoperative skin treatment regimens available to help maximize resurfacing techniques.15,16 Tretinoin and glycolic acid are the most commonly used agents preoperatively, and are utilized for their exfoliative and rejuvenating effects to improve the skin’s response to ablative wounding. Additionally, a preoperative course of topical hydroquinone or hydroquinone mixtures (e.g., tretinoin, hydroquinone, and hydrocortisone) can help to reduce the risk of postoperative hyperpigmentation in those patients with darker complexions.15,17 The authors advocate for prophylactic treatment of all patients, with or without a known history of herpes labialis, with a regimen of acyclovir 800 mg orally three times a day. This course is started 2 days preoperatively and continued for 10 to 14 days after the resurfacing procedure, or until re-epithelialization is complete. Although rhytidectomy can be performed under local anesthetic, the addition of simultaneous laser resurfacing is advised against because many patients may still experience discomfort from areas that could not be fully anesthetized, as well as further discomfort from being supine for several hours while awake. Intravenous sedation in addition to a local anesthetic could be considered in the correct patient population; however, the authors prefer the use of a general anesthetic for patient comfort. Precautions should be taken with the use of lasers in the setting of an inhaled anesthetic or oxygen, given the known risk of airway fires. Rhytidectomy begins with proper incision placement and concludes with meticulous closure resulting in well-hidden scars without changes in hairline position. This is central to achieve long-term patient satisfaction, by giving patients the freedom to style their hair without concerns of their scars showing.9 The senior author’s technique for the extended superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS) rhytidectomy, including incision planning, has previously been described in detail, and relevant points are now highlighted.9 Utilizing a submental incision, the rhytidectomy begins by addressing the problematic areas within the neck. This may include submental, submandibular, and jowl liposuction, as well as anterior cervical platysma plication using the senior author’s previously described Kelly-Clamp technique.9 The neck skin is undermined completely in a subcutaneous plane using facelift scissors freeing the platysma from the overlying skin. Using a no. 15 scalpel blade, the postauricular incision is started at the earlobe and continued along the posterior surface of the concha (not in the postauricular sulcus). At the level of the helical insertion or eminence of the concha, the incision is continued posteriorly with a gentle curve into the hairline but not parallel to the hairline. The incision should be beveled in the hair-bearing region, and the posterior skin flap is partially elevated maintaining the plane of dissection in the hair-bearing region deep to the roots of the hair follicles and superficial to the fascia of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Postauricular skin flaps should then be elevated in the immediate subcutaneous plane and connected with the neck skin elevation. From a preauricular aspect, beginning at the level of the helical insertion, dissection is carried forward in the subcutaneous plane and continued into the malar region just above the zygomatic arch in the subcutaneous plane extending just inferior to the orbicularis oculi muscle. This allows the dermal ligamentous attachments to the malar eminence to be released. Subcutaneous dissection is continued approximately 4 to 6 cm medially in the preauricular region connecting down to the elevated neck and postauricular flap allowing visualization of the neck–face interface at or below the mandibular margin into the neck (▶ Fig. 10.2). Fig. 10.2 Demonstration of the neck–face interface (highlighted area), or junction of SMAS (**) with the platysma (*), following elevation and connection of facial and neck subcutaneous dissections. An incision is then made in the SMAS extending from the inferior border of the zygomatic arch at the malar eminence diagonally down to the level of the earlobe and then continuing inferiorly 1 cm in front of the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid. Dissection should then be carried out underneath the platysma muscle at approximately 3 to 4 cm. The first centimeter of SMAS elevation is performed with horizontal scissor dissection overlying the parotid gland. Further elevation of the SMAS is performed by spreading the scissors in a more vertical fashion, forming tunnels and bridges as the dissection is carried anteriorly.9 Just above the mandibular margin, dissection is continued anteriorly superficial to the masseter muscle over the premasseteric fascia in a deep sub-SMAS plane. The marginal mandibular nerve often is easily visualized in this transition from the neck up and over the mandibular inferior border. When indicated, elevation should then extend superficial to the level of the zygomaticus muscle into the midcheek region. At this point there is a significant amount of skin elevated in addition to the SMAS, creating two separate flaps for biplane vector suspension and redraping.9 The suspension of the midface and jowl tissues is accomplished by advancing the SMAS–subcutaneous skin unit in a posterior-superior fashion toward the helical insertion. The superior triangular portion of the SMAS is advanced, and the redundant preauricular portion excised. This is suspended with a buried 0 polyglactin 910 suture (Vicryl, Ethicon Inc., Somerville, New Jersey) at the level of the helical insertion and the postauricular mastoid fascia. Then 3–0 poliglecaprone 25 sutures (Monocryl, Ethicon) are used to reinforce the platysma-SMAS unit in the mastoid, infra-auricular, and preauricular areas. The skin is advanced in a more posterior vector with 2 to 3 cm of undermined skin in the preauricular region remaining. The skin from the neck is also advanced toward the posterior mastoid hairline, and rotated superiorly. A single suspension staple is then placed high in the postauricular incision. The hair-bearing portions are approximated with staples allowing maintenance of the postauricular hairline and avoiding step-off deformities. A drain attached to a closed suction bulb system is placed in the neck portion of the wound on either side. The skin in the preauricular and tragal region is trimmed judiciously, with care taken to ensure that the earlobe is supported in a superior fashion to avoid a Satyr’s ear deformity. The periauricular skin should be redraped and tailored so that there is no tension on incision line closure. Two simple interrupted 6–0 nylon sutures are used to reapproximate the ear lobule and remain in place for 10 days. The remaining incision lines are sutured with running interlocking 5–0 plain catgut sutures, and after 1 week, if they have not already dissolved, they are removed.9 Preoperatively all patients undergo facial cleansing and washes with Septisol (Sandent Co., Murfreesboro, Tennessee). The authors use a Lumenis Encore Ultrapulse 5000 (Coherent Inc., Palo Alto, California) for full-face CO2 laser resurfacing. The most commonly used settings by the senior author are depicted in ▶ Table 10.2 and ▶ Table 10.3. The first laser pass on the face, excluding the upper and lower eyelids and preauricular area, is performed at an energy of 80 mJ, fluence of 6.0 J/cm2, power of 48 W, and a density of 5, with a square pattern to move along the face expeditiously while maintaining control over the portions of the flap that are treated with the laser. Treatment areas Pulse energy (mJ) Fluence (J/cm2) Pulse width (Hz) Power (W) Density Initial pass Perioral, lips, chin 80 6.0 600 48 5 Cheeks 80 6.0 600 48 5 Forehead 80 6.0 600 48 5 Eyelids 70 5.3 600 42 4 Additional pass* Glabella, crow’s-feet 70 5.3 600 42 4 Perioral, lips, chin 70 5.3 600 42 4 Cheeks 70 5.3 600 42 4 Additional pass** Previously treated areas 60 4.5 600 36 4 Note: *Reserved for treatment of moderate to severe rhytids. **Reserved only for the most severe rhytids; rarely performed by the authors. Treatment areas Pulse energy (mJ) Fluence (J/cm2) Pulse width (Hz) Power (W) Density Initial pass Preauricular undermined skin 70 5.3 600 42 4 Inferior mandibular border 70 5.3 600 42 4 Additional pass* Preauricular undermined skin 60 4.5 600 36 4 Inferior mandibular border 60 4.5 600 36 4 Note: *Not routinely performed by the authors. Once the first pass is made, the surface char should be gently wiped and removed with wet and dry gauze. The second pass is directed to areas of deeper wrinkles, such as the glabella, crow’s-feet, and perioral region, and should be performed at an energy of 70 mJ, fluence of 5.3 J/cm2, power of 42 W, and a density of 4. Similarly, the first treatment of the eyelids and preauricular area should be at the same settings. This is performed with an appropriate rectangular pattern to address each anatomical area (e.g., smaller for the eyelids). A 2- to 3-cm area of preauricular skin is left untreated by the senior author; however, if desired the surgeon may “taper” over the area corresponding to the subcutaneous skin elevation (▶ Fig. 10.3). Tapering involves decreasing the density to 4, while decreasing the fluence from 70 mJ to 60 mJ, which allows the surgeon to safely go over the 2- to 3-cm area of undermined skin in the preauricular region and jawline for blending and feathering (▶ Table 10.3). Fig. 10.3 Patient intraoperatively following rhytidectomy and full-face resurfacing sparing 2 cm of preauricular undermined skin and along the inferior mandibular border (highlighted area).

10.2 Patient Selection

10.3 Preoperative Care

10.3.1 Anesthesia

10.4 Rhytidectomy Technique

10.5 Laser Resurfacing Technique

10.5.1 Carbon Dioxide Laser

Simultaneous Full-Face Laser Resurfacing in the Setting of Facelift Surgery

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree