Simple Mastectomy

Elizabeth A. Shaughnessy

Before the advent of sentinel node biopsy in the assessment of the axilla, the simple or total mastectomy was a procedure performed primarily in the context of extensive ductal carcinoma in situ. The procedure is now much more frequently utilized in a variety of contexts. Women with a family history or carriers of a deleterious mutation in BRCA1, BRCA2, or PTEN, armed with the knowledge that they may carry a genetic predisposition to develop breast cancer, are pursuing prophylactic mastectomy in increasing numbers, often paired with immediate reconstruction. Young women exposed to breast radiation before the age of 19, in the setting of mantle radiation for Hodgkin lymphoma, survived their malignancy only to find themselves at increased risk for medial breast cancers 10 to 20 years later (1). Rather than deal with yet another malignancy, many of these women are seeking bilateral prophlylactic mastectomy or bilateral mastectomy (one side prophylactic) with the diagnosis of a breast cancer. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy following the initial diagnosis of a breast malignancy has significantly increased over the past 10 years (2,3), primarily due to patient preference, but also associated with the knowledge of increased risk with the above-mentioned genetic mutations.

Invasive carcinoma of the breast can be addressed by partial mastectomy or mastectomy if unifocal, usually with sentinel lymph node biopsy preceding it. In the presence of nodal involvement with breast cancer, surgical management of the breast may be paired with a full axillary lymph node dissection (see Chapter 12). Multicentricity would preclude partial mastectomy in the delivery of the standard of care. Multifocality may or may not allow for breast conservation, depending on the extent of disease. Although guidelines would suggest that resection of up to a quarter of the breast leaves an acceptable postoperative result, the perspective of the general public is one of increased expectations regarding the cosmetic end result. The use of breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in assessing the extent of disease in a patient with dense tissues diagnosed with breast cancer is thought to be linked to a greater number of suspicious lesions identified within the breast, suggestive of multicentricity or multifocality. Consequently, more women opt for mastectomy rather than pursue additional biopsies that add to their anxiety or to the delay in access to systemic treatment. The incidence of a synchronous contralateral breast cancer in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer is reported as 3% to 4% (4) and is supported by MRI (5). Whether the second breast cancer would become

clinically relevant in that woman’s lifetime remains to be seen. Doing a routine MRI then, outside the context of a dense breast on mammography in a patient with a family history, would not be considered the standard of care.

clinically relevant in that woman’s lifetime remains to be seen. Doing a routine MRI then, outside the context of a dense breast on mammography in a patient with a family history, would not be considered the standard of care.

In older patients with very large breasts, performance of a unilateral total mastectomy may be sufficient to throw off their sense of balance. Should a unifocal cancer need resection, strong consideration should be given to management with breast conservation to avoid the issue of imbalance. A multiplicity of medical problems may also serve to place the patient at high risk for complications from a general anesthetic; breast conservation would likely allow resection of a unifocal breast cancer under local anesthetic, with monitored anesthesia care. An absolute contraindication to total mastectomy as a method of managing the breast does not exist, except perhaps as an initial method of control with metastatic breast cancer or inflammatory breast cancer should the primary not require palliation. Generally speaking, mastectomy is done in the context of metastatic breast cancer for purposes of palliation. The data regarding whether to use it following an excellent response to chemotherapy for survival benefit is suggested by the data but not established firmly statistically (6,7,8).

Mastectomy is an option in the context of large breast sarcomas. In general, these can be managed using breast conservation, with attention to obtaining negative margins, unless recurrent or with the rare angiosarcoma, where margins of at least 3 cm are generally necessary and rarely obtained within the context of conservation (9).

Relative contraindications usually take the form of patients who present with inflammatory breast cancer, chest wall or skin involvement, and metastatic breast cancer. These patients generally would undergo chemotherapy initially as part of their therapy. A total mastectomy at a later date may or may not be indicated, depending on the response. Some patients cannot undergo a general anesthetic at the initial time of presentation, although there have been reports of use of the tumescent technique and performance of a total mastectomy undergoing local anesthesia. As patients live longer, we deal more frequently with patients who have had drug-eluting coronary artery stents placed, facing the contraindication to take the patient off clopidogrel out of concern that the stent could thrombose within the first 6 months. Patients have suffered myocardial infarction within a short time of receiving their diagnosis of breast cancer; a general anesthetic within the first few months will place that individual at increased risk of mortality under a general anesthetic. One can pursue treatment initially with systemic agents, in collaboration with a medical oncologist, with definitive resection to take place later.

Very rare issues of breast trauma under extenuating circumstances, with trauma incurred while taking aspirin, warfarin or clopidogrel, may require a mastectomy for full resection with negative margins.

Neoadjuvant therapy may enable the performance of a partial mastectomy when the patient presents with a large tumor relative to the size of the breast in approximately 25% to 30% of those who undergo chemotherapy first (10). Yet, the majority of these patients do not have a sufficiently complete response to allow breast conservation, which may not be evident before embarking on breast conservation. The clinician may be fooled into interpreting a greater response than is present, on the basis of physical findings. The mass present may be surrounded by small microscopic islands within the original tumor volume that will not yield negative margins upon full resection (nonconcentric response). The answer may not be known until the final pathology result returns. A completion total mastectomy may then be indicated.

In the context of the patient who will undergo immediate reconstruction at the time of mastectomy, the surgeon needs to consider whether a sentinel lymph node should be included in the operative plan. The performance of a sentinel node, including blue dye, can be somewhat distracting in the dissection of the tissue planes but more so for the plastic surgeon; however, this issue is surmountable with time and frequency of experience. Intraoperative assessment of the sentinel node by touch preparation or by frozen

section does not yield a positive result in all cases of metastatic disease to the sentinel nodes, sometimes the node may be too small to utilize for frozen section, and the final answer on permanent section takes several days. In anticipation of the reconstructive process, armed with the knowledge that a positive status for a sentinel node may not be known for several days, consider performance of the sentinel node in advance of the definitive extirpation. In that fashion, a completion axillary lymph node dissection can be performed at the time of mastectomy without concern for disruption of the reconstructed autologous tissue mound. Performance of an axillary lymph node dissection after tissue expander placement can be performed at a later date, especially if the approach was via muscle splitting as opposed to a lateral insertion approach. Yet the pectoralis muscles will be tighter, depending on the degree of expander fill, and may not allow as much abduction of the arm in positioning.

section does not yield a positive result in all cases of metastatic disease to the sentinel nodes, sometimes the node may be too small to utilize for frozen section, and the final answer on permanent section takes several days. In anticipation of the reconstructive process, armed with the knowledge that a positive status for a sentinel node may not be known for several days, consider performance of the sentinel node in advance of the definitive extirpation. In that fashion, a completion axillary lymph node dissection can be performed at the time of mastectomy without concern for disruption of the reconstructed autologous tissue mound. Performance of an axillary lymph node dissection after tissue expander placement can be performed at a later date, especially if the approach was via muscle splitting as opposed to a lateral insertion approach. Yet the pectoralis muscles will be tighter, depending on the degree of expander fill, and may not allow as much abduction of the arm in positioning.

Further preoperative considerations would include the possibility of coordination with physicians or surgeons in other disciplines. If immediate reconstruction will be arranged at the time of the extirpation, then the patient must be seen by the plastic surgeon and a coordinated plan for surgery on a mutually available date should be established. If the patient is to have neoadjuvant chemotherapy, then coordination with the medical oncologist for initiation of the treatment and coordinated communication to streamline the patient’s return for surgical planning. Should there be a question of postsurgical radiation, consultation with the radiation oncologist preoperatively should be considered before immediate reconstruction is pursued. Radiation can distort an autologous tissue flap; radiation of the chest wall in the presence of tissue expanders can often be done but is best planned with the radiation oncologist in light of any extenuating circumstances (11).

If a prophylactic mastectomy is planned, the breasts should be appropriately screened for an asymptomatic breast cancer, with a mammogram and possible breast MRI if appropriate. If done for breast cancer, a mammogram should be an integral part of the planning. A breast MRI may be considered if chest wall invasion or skin involvement is a concern, to delineate and potentially clinically stage the cancer.

In the immediate preoperative setting, prophylactic antibiotics, usually a cephalosporin administered approximately 30 minutes before incision, can reduce the rate of wound infection by 40% or more. In light of the fact that these surgeries are done under a general anesthetic, planning for deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis may include compression boots, an injection of subcutaneous heparin, or a single dose of low-molecular-weight heparin in the high-risk population.

The intent of the total mastectomy is to remove the breast, sparing the lymph nodes. In the past, the anatomical extent of the breast was probably less well understood as evidenced by studies such as the NSABP B-04 study (12). This trial, in which women underwent mastectomy with or without axillary lymph node dissection, demonstrated an average of six lymph nodes with the breast specimen among those patients randomized to mastectomy alone. Clearly, how to remove the breast but spare the lymph nodes is not always a clear issue, but it is possible.

Studies that have examined local recurrences following total mastectomy indicate the areas where breast tissue is most likely retained are inferiorly and laterally in the tail of Spence. Certainly, this becomes a sticky issue when attempting to maintain the connective tissue of the inframammary fold in place for reconstructive purposes.

Positioning

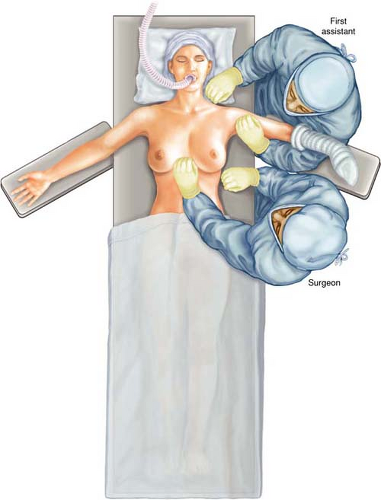

The patient is placed in the supine position with the ipsilateral upper extremity on an armboard level with the table. I discourage the use of a roll along the lateral thorax as it places the arm in extension and abduction, placing the patient at risk for brachial plexopathy. Surgeon and assistant are at either side of the armboard; they can exchange

position, if so desired (Fig. 18.1). If desired, the foot of the table can be angled slightly to the site opposite the side for surgery to allow greater space between the armboard and anesthesia staff. This is utilized only for a unilateral approach.

position, if so desired (Fig. 18.1). If desired, the foot of the table can be angled slightly to the site opposite the side for surgery to allow greater space between the armboard and anesthesia staff. This is utilized only for a unilateral approach.

Perioperative Management

Incision

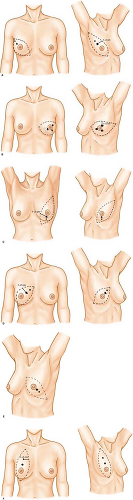

The upper anterior arm, breast, ipsilateral thorax, and lower neck are prepared and draped. The incision will vary, depending on whether skin-sparing is intended. If skin-sparing is not intended, an incision that allows for a flat closure against the chest wall will enable greater ease in wearing a breast prosthesis after healing. A variety of incisions have been described and are mentioned in Figure 18.2. Historically, the nipple and

areolar complex are included in the tissue excised, and the tumor generally lies deep to the skin excised. That stated, as long as the tumor is away from the skin, the surgeon typically utilizes an elliptical incision.

areolar complex are included in the tissue excised, and the tumor generally lies deep to the skin excised. That stated, as long as the tumor is away from the skin, the surgeon typically utilizes an elliptical incision.

Inspect the breast and note its shape in the supine position. I note the extent to which the breast extends into the axilla laterally (Fig. 18.3). Choose a point under the hair-bearing area, along the posterior axillary fold, and mark it on the skin (Fig. 18.3A). If a

line was drawn through this point and the nipple, going to the opposite side of the breast (the lower inner quadrant), draw another point at the most medial aspect of the breast or slightly beyond. At a right angle relative to this imaginary line, first pull the breast gently down, and draw a line between these two points (Fig. 18.3B). When released, the skin displays an arc. Similarly, lift the breast up at a right angle to the imaginary line formed by the original two points and draw a straight line between these points. Once released, this results in a drawn ellipse. Before incising, check to make sure that sufficient skin is available for closure by approximating the skin with hands; rarely must I readjust what was planned. Care should be taken to prevent closing under tension.

line was drawn through this point and the nipple, going to the opposite side of the breast (the lower inner quadrant), draw another point at the most medial aspect of the breast or slightly beyond. At a right angle relative to this imaginary line, first pull the breast gently down, and draw a line between these two points (Fig. 18.3B). When released, the skin displays an arc. Similarly, lift the breast up at a right angle to the imaginary line formed by the original two points and draw a straight line between these points. Once released, this results in a drawn ellipse. Before incising, check to make sure that sufficient skin is available for closure by approximating the skin with hands; rarely must I readjust what was planned. Care should be taken to prevent closing under tension.

If skin-sparing is intended, several choices are possible (Fig. 18.4). Since skin-sparing is usually applied only when immediate reconstruction is coordinated, the incision I utilize is chosen in conjunction with the plastic surgeon with whom I am operating. The essence is that at least part of the incision, if not all, is close to the areolar border.

Raising the Skin Flaps

In utilizing an incision that traverses the skin of the hemithorax, the surgeon has a choice of several different retractors that can be utilized successfully—Adair tenaculae,

skin rakes, or skin hooks. This usually reflects the surgeon’s training and preference. Retraction focuses on lifting the skin at a right angle to the skin surface, with the surgeon placing gentle tension down toward the chest wall (Fig. 18.5

skin rakes, or skin hooks. This usually reflects the surgeon’s training and preference. Retraction focuses on lifting the skin at a right angle to the skin surface, with the surgeon placing gentle tension down toward the chest wall (Fig. 18.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree