Postoperative rhinoplasty deformities—such as displacement or distortion of anatomic structures, inadequate surgery resulting in under-resection of the nasal framework, or over-resection caused by overzealous surgery—require a secondary rhinoplasty. Success in secondary rhinoplasty, therefore, relies on an accurate clinical diagnosis and analysis of the nasal deformities, a thorough operative plan to address each abnormality, and a meticulous surgical technique. Septal cartilage is the grafting material of choice for rhinoplasty; however, auricular cartilage and rib cartilage are used in secondary rhinoplasty. This article discusses the steps involved in the external approach to secondary rhinoplasty.

Rhinoplasty is generally considered to be one of the most difficult procedures in cosmetic surgery, and the incidence of postoperative nasal deformities that require secondary rhinoplasty varies from 5% to 12%. Deformities arising from an earlier rhinoplasty can range in severity from mild asymmetry of the nasal tip or dorsum to severe distortion and collapse of the osseocartilaginous framework. Regardless of the severity, the causes of postoperative rhinoplasty deformities are most frequently related to: (1) displacement or distortion of anatomic structures, (2) inadequate surgery resulting in under-resection of the nasal framework, or (3) over-resection caused by overzealous surgery.

Success in secondary rhinoplasty, therefore, relies on an accurate clinical diagnosis and analysis of the nasal deformities, a thorough operative plan to address each abnormality, and a meticulous surgical technique. Reconstruction of the osseocartilaginous framework is the foundation for obtaining consistent aesthetic and functional results in secondary rhinoplasty. Septal cartilage is generally considered to be the preferred grafting material for most applications in rhinoplasty, but secondary rhinoplasty frequently necessitates alternative sources of grafting material when there are severe structural deformities of the nasal framework or when insufficient amounts of septal cartilage are available. In some cases, auricular cartilage may be suitable; however, rib cartilage provides the most abundant source of grafts and has proved to be the most reliable in the authors’ hands when addressing major secondary deformities.

Although adequate results may be obtained with the endonasal technique in certain circumstances, the limited dissection and exposure offered by the endonasal approach often does not permit accurate assessment, intraoperative diagnosis, and appropriate treatment of complex anatomic problems. The authors, therefore, prefer addressing most secondary rhinoplasty deformities by the external approach to help ensure consistent aesthetic and functional results.

Clinical analysis and operative planning

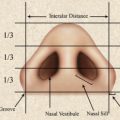

A thorough nasal analysis and precise anatomic diagnosis of each deformity ( Table 1 ) is a key step for achieving optimal results in secondary rhinoplasty. Preoperative evaluation begins by defining the deformity, which is accomplished by a detailed history, physical examination, and complete aesthetic, facial, and nasal analysis. The nose should be examined and analyzed from top to bottom. Starting superiorly, the height, the width, and the symmetry of the dorsum should be noted. The nasofrontal angle normally begins at the supratarsal crease and may be noted to be lower in patients with an over-resected dorsum. The contour of the dorsum should be assessed and any irregularity should be noted. The width of the bony pyramid and upper lateral cartilages should be inspected for asymmetry, collapse, and for the presence of an “inverted-V” deformity. The supratip area is evaluated for the presence of a “polly-beak” deformity or absence of an appropriate supratip break. The nasal tip is evaluated in terms of its projection and its rotation. The lower lateral cartilages are assessed for their symmetry, width, position, and symmetry of the tip-defining points. The alar rims are inspected for collapse or retraction. The columella is examined for increased or decreased show. The columellar-lobular and columellar-labial angles are evaluated to ascertain the desired angulation. The internal nasal examination evaluates patency of the nasal valves, position and integrity of the septum, and state of the turbinates.

| Dorsum | Tip |

|---|---|

| Over-resection | Asymmetry |

| Dorsal irregularity | Alar collapse |

| “Polly-beak” deformity | Alar retraction |

| “Inverted-V” deformity | Hanging columella |

| Saddle deformity | Retracted columellar-labial angle |

| Over-rotation of tip |

Another important aspect of the preoperative evaluation is the assessment of the patient’s psychological status and stability. It has been estimated that 5% of patients seeking cosmetic surgery have body dysmorphic disorder, which is a preoccupation with a slight or imagined defect with some aspect of their physical appearance that leads to significant disruption of daily functions. It is important to distinguish patients with a legitimate cosmetic or functional concern from patients who are hyperconcerned about minor imperfections of their nose.

After the patient has been deemed a good psychological candidate and the deformities defined, the goals of the surgery should be established and an operative plan formulated to address each abnormality. The operative goals are individualized for each patient according to the deformity. The goals may be to augment the dorsum, to straighten a dorsally deviated septum, to lower the supratip area, to correct tip asymmetry and alar collapse, to decrease columellar show, and so forth. If the existing osseocartilaginous framework is under-resected, the amount and location of further reduction are determined. If the nasal framework has been over-resected, the missing tissues and the need for augmentation are determined. Secondary surgery is usually deferred until 12 months after the previous rhinoplasty.

Assessment of grafting requirements

A key component of operative planning in secondary rhinoplasty includes assessment of the grafting requirements and determination of the potential source of grafting materials that will be required. Secondary rhinoplasty often necessitates significant numbers of grafts, such as spreader graft, lateral crural strut grafts, and dorsal onlay grafts when structural deformities result from previous procedures. The authors prefer autogenous cartilage for any nasal framework replacement. Successful use of irradiated homologous rib cartilage has been reported in the past, but problems with infection, absorption, and warping have limited its routine use in secondary rhinoplasty (Dingman RO, personal communication, 1980).

Septal cartilage is generally the preferred grafting material in primary and secondary rhinoplasty. The integrity of the nasal septum, and thus its availability for use as cartilage grafts, can be assessed during the office consultation and examination by gently palpating the septum with a cotton tip applicator. There are several advantages to using septal cartilage. A large amount of septal cartilage and septal bone can be harvested from the same operative field without the morbidity of an additional donor site. Compared with auricular cartilage, septal cartilage is more rigid, provides better support, and does not have convolutions. Septal cartilage is preferably used as a columellar strut, spreader grafts between the upper lateral cartilages and the septum, and lateral crural strut grafts to support or replace parts of the lower lateral cartilage complexes. When a sufficient quantity is available, it may also be used as a dorsal onlay graft for minimal amounts of dorsal augmentation.

Severe deformities or a paucity of available septal cartilage requires an alternative source of grafting material. The auricle can provide a modest amount of cartilage for nasal reconstruction. Using a postauricular approach, the amount of harvested conchal cartilage can be maximized without compromising ear protrusion by preserving sufficient cartilage in 3 key areas: (1) the inferior crus of the antihelix, (2) the root of the helix, and (3) the area where the concha cavum transitions into the posterior-inferior margin of the external auditory canal. A vertical incision is created on the posterior aspect of the auricle, and dissection is carried down through the perichondrium. A 27-gauge needle dipped in methylene blue is percutaneously placed every half centimeter along the inner aspect of the antihelical fold to tattoo the cartilage along the planned excision path to maximize the amount of harvested cartilage while ensuring that sufficient antihelical contour is maintained. Dissection proceeds along the anterior and the posterior surface of the conchal bowl, and a kidney-bean shaped piece of conchal cartilage is harvested while leaving sufficient cartilage at the aforementioned key areas for support.

Because of its flaccidity and convolutions, auricular cartilage is best used when these characteristics are desired. Auricular cartilage is usually used for reconstructing the lower lateral cartilage complex, for small onlay grafts, or for placement in the columella to provide tip support. However, it is a second choice to septal cartilage because of the inherent difficulty in obtaining and maintaining the desired shape and contour. While initial results of dorsal augmentation with auricular cartilage are often satisfactory, surface irregularities can become apparent with the passage of time. Furthermore, the irregular contour and the limited supply of auricular cartilage often preclude its use.

Autogenous rib cartilage provides the most abundant source of cartilage for graft fabrication and is the most reliable when structural support or augmentation is needed, and therefore has been the authors’ graft material of choice for secondary rhinoplasty when sufficient septal cartilage is not available.

Various types of alloplastic materials have been used in rhinoplasty, including: (1) solid silicone, (2) high-density porous polyethylene (Medpor, Porex Surgical Inc, College Park, GA, USA), and (3) expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-Tex, W.L. Gore Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA). Alloplastic materials have the advantages of being easy to use, readily available, and having an unlimited supply. Unfortunately, because of their permanent nature, many of these alloplastic materials are fraught with long-term complications, such as infection, migration, extrusion, and palpability. Thus, autogenous tissue continues to be the authors’ preferred source of grafts.

Assessment of grafting requirements

A key component of operative planning in secondary rhinoplasty includes assessment of the grafting requirements and determination of the potential source of grafting materials that will be required. Secondary rhinoplasty often necessitates significant numbers of grafts, such as spreader graft, lateral crural strut grafts, and dorsal onlay grafts when structural deformities result from previous procedures. The authors prefer autogenous cartilage for any nasal framework replacement. Successful use of irradiated homologous rib cartilage has been reported in the past, but problems with infection, absorption, and warping have limited its routine use in secondary rhinoplasty (Dingman RO, personal communication, 1980).

Septal cartilage is generally the preferred grafting material in primary and secondary rhinoplasty. The integrity of the nasal septum, and thus its availability for use as cartilage grafts, can be assessed during the office consultation and examination by gently palpating the septum with a cotton tip applicator. There are several advantages to using septal cartilage. A large amount of septal cartilage and septal bone can be harvested from the same operative field without the morbidity of an additional donor site. Compared with auricular cartilage, septal cartilage is more rigid, provides better support, and does not have convolutions. Septal cartilage is preferably used as a columellar strut, spreader grafts between the upper lateral cartilages and the septum, and lateral crural strut grafts to support or replace parts of the lower lateral cartilage complexes. When a sufficient quantity is available, it may also be used as a dorsal onlay graft for minimal amounts of dorsal augmentation.

Severe deformities or a paucity of available septal cartilage requires an alternative source of grafting material. The auricle can provide a modest amount of cartilage for nasal reconstruction. Using a postauricular approach, the amount of harvested conchal cartilage can be maximized without compromising ear protrusion by preserving sufficient cartilage in 3 key areas: (1) the inferior crus of the antihelix, (2) the root of the helix, and (3) the area where the concha cavum transitions into the posterior-inferior margin of the external auditory canal. A vertical incision is created on the posterior aspect of the auricle, and dissection is carried down through the perichondrium. A 27-gauge needle dipped in methylene blue is percutaneously placed every half centimeter along the inner aspect of the antihelical fold to tattoo the cartilage along the planned excision path to maximize the amount of harvested cartilage while ensuring that sufficient antihelical contour is maintained. Dissection proceeds along the anterior and the posterior surface of the conchal bowl, and a kidney-bean shaped piece of conchal cartilage is harvested while leaving sufficient cartilage at the aforementioned key areas for support.

Because of its flaccidity and convolutions, auricular cartilage is best used when these characteristics are desired. Auricular cartilage is usually used for reconstructing the lower lateral cartilage complex, for small onlay grafts, or for placement in the columella to provide tip support. However, it is a second choice to septal cartilage because of the inherent difficulty in obtaining and maintaining the desired shape and contour. While initial results of dorsal augmentation with auricular cartilage are often satisfactory, surface irregularities can become apparent with the passage of time. Furthermore, the irregular contour and the limited supply of auricular cartilage often preclude its use.

Autogenous rib cartilage provides the most abundant source of cartilage for graft fabrication and is the most reliable when structural support or augmentation is needed, and therefore has been the authors’ graft material of choice for secondary rhinoplasty when sufficient septal cartilage is not available.

Various types of alloplastic materials have been used in rhinoplasty, including: (1) solid silicone, (2) high-density porous polyethylene (Medpor, Porex Surgical Inc, College Park, GA, USA), and (3) expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-Tex, W.L. Gore Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA). Alloplastic materials have the advantages of being easy to use, readily available, and having an unlimited supply. Unfortunately, because of their permanent nature, many of these alloplastic materials are fraught with long-term complications, such as infection, migration, extrusion, and palpability. Thus, autogenous tissue continues to be the authors’ preferred source of grafts.

Harvesting rib cartilage

Rib cartilage is a versatile grafting material in secondary rhinoplasty. The grafting requirements and planned uses dictate the choice of the rib to be harvested. It is often possible to construct all required grafts from a single rib, and the surgeon should choose the cartilaginous portion of a rib that provides a straight segment. The authors prefer to harvest cartilage from the fifth, sixth, or seventh rib, depending on the rib that is the longest and straightest. If additional grafts are needed, a part or the entire cartilaginous portion of an adjacent rib may be harvested.

The rib cartilage graft may be harvested from either the patient’s left or right side; however, harvesting from the patient’s left side facilitates a 2-team approach. In female patients, the incision is marked several millimeters superior to the inframammary fold and measures 5 cm in length ( Fig. 1 ). In males, the incision is usually placed directly over the chosen rib to facilitate the dissection.

To decrease the chances of postoperative wound infections, the chest is prepared and draped separately from the nose, and separate surgical instruments are used to prevent cross-contamination. A 5-cm skin incision is created along the inframammary fold with a 15-blade scalpel, and the subcutaneous tissue is divided with electrocautery. Once the muscle fascia is reached, the surgeon palpates the underlying ribs and divides the muscle and fascia with electrocautery directly over the chosen rib. The dissection should be carried medially until the junction of the rib cartilage and sternum can be palpated. Identification of the lateral extent of dissection is facilitated by the subtle change in color of the rib at the bony-cartilaginous junction; the cartilaginous portion is generally off-white in color, whereas the bone demonstrates a distinct reddish-gray hue.

After the selected rib is exposed, the perichondrium is incised along the long axis of the rib. A Dingman elevator is used to elevate the perichondrium superiorly and inferiorly from the cartilaginous rib ( Fig. 2 ). Perpendicular cuts are also made in the perichondrium at the most medial and lateral aspects of the longitudinal incision to facilitate reflection of the perichondrium. If needed, a 1.5-cm by 5-cm strip of perichondrium can be harvested from the anterior surface of an adjacent rib for use as a camouflaging graft .