Chapter 27 Secondary Reconstruction of the Flexor Pollicis Longus Tendon

Outline

The technical execution of the various surgical maneuvers used in secondary reconstruction of the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) (Box 27-1) are relatively straight forward to any hand surgeon versed in the techniques of flexor tendon surgery. However, decision making as to what is done in any particular circumstance is complicated by various anatomical peculiarities of the FPL tendon compared to the flexor system of the finger, the timing of presentation, the plethora of treatment options, and, in some instances, by the differing flexion needs of the thumb in different individuals.

Primary Repair of Flexor Pollicis Longus by Preference

Recent practice (see Chapter 16) has established that primary repair of the FPL tendon is desirable where possible and 70% to 80% of the results will be within the excellent or good range, although it should be noted that “excellent” in our current classifications does not imply return to normal function. Nevertheless, these results are better than the 30° to 40° degrees of movement previously perceived as necessary to good function of the interphalangeal (IP) joint of the thumb.1,2 With various modern suturing techniques of primary repair, early mobilization can also be progressed safely to completion without rupture of the repair.3,4 Direct repair may be possible as late as 3 to 4 weeks after injury but, more frequently, in my experience, there is sufficient shortening of the muscle within a few days as to make direct primary repair without proximal tendon lengthening impossible without the IP being flexed to a degree from which it never recovers extension.

Primary Grafting of Zone 3 and 4 Injuries

The FPL is rarely divided in zone 3, within the thenar muscles, where it is deeply placed. However, surgical repair is difficult in zone 3 as access is past the digital nerves of the thumb and through the thenar muscles, with risk to the motor branches of the median nerve. That loss of thumb sensation or opposition are greater disabilities than loss of terminal flexion should be considered before extending an already extensive injury in this zone to repair the tendon directly.5 Any direct tendon repair in zone 3 will also be surrounded by edematous and swollen muscle during rehabilitation. Except where the injury is a small puncture wound of the thenar eminence and dissection to the site of division can be precise and small, there is justification for the approach recommended by Matev (1983) of replacing the tendon from the wrist to its distal attachment with a tendon graft, even if seen immediately.6 In these injuries, the proximal end of the tendon is frequently found retracted to the wrist. When presentation is even only slightly delayed, the distal end of the tendon may be adherent within the muscle tunnel and require careful release from adhesions through the digital exposure, if necessary leaving the end itself within the muscles by division of the tendon just proximal to the metacarpophalangeal joint.

Techniques to Extend Primary Repair

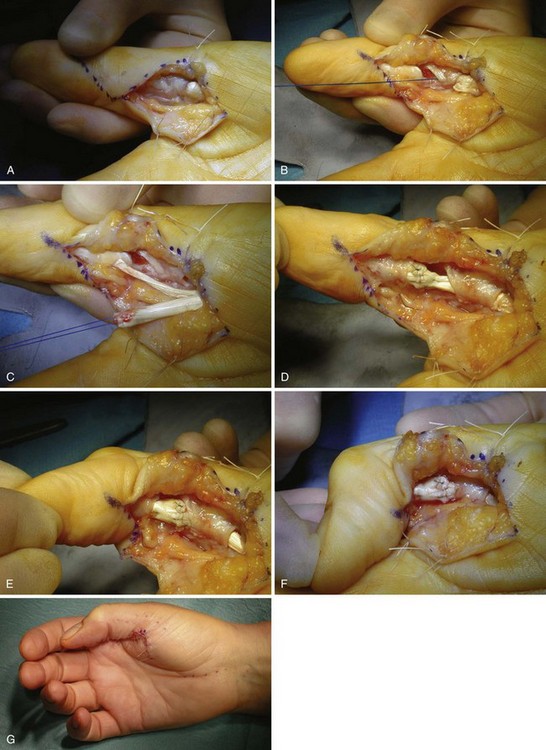

In general, the use of primary flexor surgery can be extended and secondary surgery avoided by (1) using techniques that allow one to do more primary repairs, such as undertaking delayed primary repairs, using proximal tendon lengthening, and using techniques such as splitting swollen tendons distally to allow their passage through the pulleys7; (2) by using techniques that reduce the failures of primary repair, such as improved rehabilitation; and (3) by re-repairing ruptures.8 Many of these techniques are applicable to the divided FPL tendon. Occasionally, the FPL may be too swollen to pass through the A1 and A2 pulleys. The technique of halving the distal end of the tendon that we described to pass a swollen flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendon through the A4 pulley7 can also be used in FPL surgery (Figure 27-1). However, the most significant problem preventing primary FPL repair is the propensity of the FPL muscle to contract after division of the tendon,9 and proximal tendon lengthening to deal with this eventuality can be considered an extension of primary repair or a technique of secondary reconstruction. This has been discussed in some detail in Chapter 16 but more from the point of view of avoiding a tightly flexed interphalangeal (IP) joint of the thumb and/or tendon rupture by primary suture under tension.

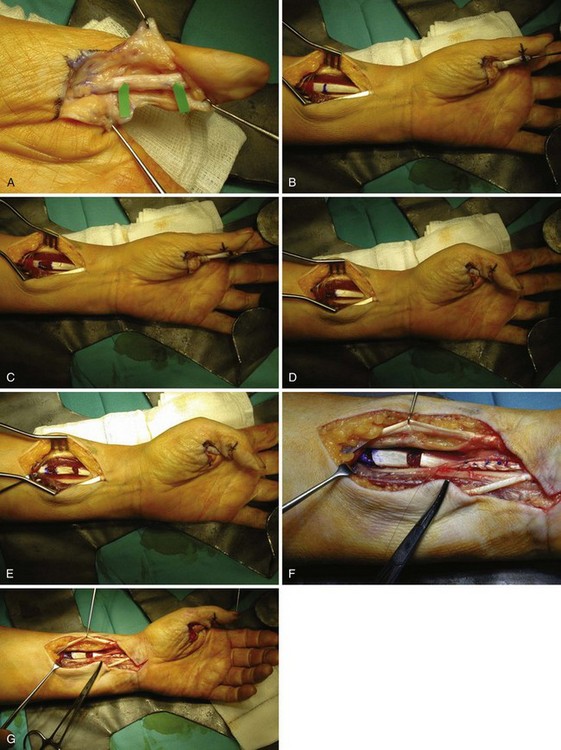

The considerable literature of the 1940–1960 period, when most presentations and repairs were delayed, presents a conflict of opinion as to whether the FPL should be repaired by interpositional grafting or by proximal tendon lengthening, either in the muscle or in the tendon at the wrist, with direct repair being entirely avoided by many authors, or exceptional, except after very early presentation for others. Urbaniak and Goldner favored direct repair when possible and used the other techniques when the tendon gap was too wide.10,11 They found the results of tendon lengthening in their unit to be better than those of interposition grafting in those cases in which direct repair was not possible. In their writings, others are more circumspect as to whether tendon lengthening gives better results than tendon grafting.5,6 This debate as to the relative merits of extending primary repair by proximal lengthening or moving on to grafting continued through the period after 1970 and remains in the literature with Schneider (1999), in Green’s Operative Hand Surgery, confessing to little experience with tendon lengthening,12 while Matev (1983) considered Z lengthening in the musculotendinous part of the tendon as a logical extension of primary suturing and preferable to grafting when the muscle has retracted but not undergone degeneration and fibrosis.6 Our experience has largely been after only slight delay of presentation, with muscle shortening sufficient for primary suture to be under tension, or significantly flex the IP joint, but before muscle degeneration. Proximal tendon lengthening within the muscle by the Le Viet technique13 has usually achieved the lengthening of up to 1 cm required in these circumstances. My experience of “Z” lengthening of the FPL tendon at the musculotendinous junction14,15 is limited and usually as an adjunct to lengthening within the muscle where this alone is not adequate (Figure 27-2). Pulvertaft (1966) wrote that a gap of  to 2 inches (3.8 to 5 cm) could be closed by this technique alone.5 The long length of FPL tendon—3 to 4 cm—at the wrist with no muscle fibers attached aids this degree of lengthening without impingement of the tendon sutures on the carpal ligament on full extension of the thumb with the wrist dorsiflexed, if the lengthening is carried out at the musculotendinous junction.10 The adjacent muscle can also be tacked around the lengthening to make it more smooth. I have no experience of Rouhier lengthening within muscle, still said to be used in France.16,17

to 2 inches (3.8 to 5 cm) could be closed by this technique alone.5 The long length of FPL tendon—3 to 4 cm—at the wrist with no muscle fibers attached aids this degree of lengthening without impingement of the tendon sutures on the carpal ligament on full extension of the thumb with the wrist dorsiflexed, if the lengthening is carried out at the musculotendinous junction.10 The adjacent muscle can also be tacked around the lengthening to make it more smooth. I have no experience of Rouhier lengthening within muscle, still said to be used in France.16,17

No FPL Repair

In respect of patients presenting after significant delay, management by doing nothing, particularly if the carpometacarpal (CMC) and metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints are functioning normally, is generally only suggested as suitable for the elderly.12 It has been my experience with several younger-than-elderly patients who have presented late with inability to flex the IP joint that they have been quite happy with the function of the thumb for their needs and, when the option of a complicated operation and a lengthy rehabilitation period is explained as the logical treatment of their problem, have declined any treatment (Figure 27-3). Doing nothing or a (relatively simple) distal fixation procedure to prevent hyperextension of the IP joint, if this is causing problems of pinching, is definitely an option to be discussed with all patients. As the variable hyperextension of this joint commonly seen, particularly in supple hands, appears to have no useful function,18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

to 1 cm in length, it is quite possible to insert a core suture into the distal end of the tendon. With divisions closer to the insertion than

to 1 cm in length, it is quite possible to insert a core suture into the distal end of the tendon. With divisions closer to the insertion than  cm, it is possible to leave the distal segment of tendon in place and anchor the suture into the distal phalanx by one of the various described techniques, after passage of the sutures through the distal segment of the tendon. While the small attached segment of tendon could be excised and any IP contracture subsequent to advancement of the proximal tendon corrected by lengthening of the proximal tendon, this seems a complicated way of achieving the same end.

cm, it is possible to leave the distal segment of tendon in place and anchor the suture into the distal phalanx by one of the various described techniques, after passage of the sutures through the distal segment of the tendon. While the small attached segment of tendon could be excised and any IP contracture subsequent to advancement of the proximal tendon corrected by lengthening of the proximal tendon, this seems a complicated way of achieving the same end.