Chapter 16 Primary Repair of the Flexor Pollicis Longus Tendon

Outline

The Problem of Flexor Pollicis Longus Retraction

It has been known that the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) tendon is more difficult to repair than the finger flexors for over 60 years. In 1937, Murphy identified this problem and highlighted the fact that retraction of the proximal end of the cut FPL tendon was almost always greater than that of the proximal ends of cut finger flexor tendons.1 Our clinical experience, and that of others more recently, would agree that the greater retraction of the cut FPL tendon is due to shortening of the FPL muscle as there is often considerable difficulty pulling the proximal tendon end out to length if FPL repair is attempted after even a short delay beyond 48 hours. It would seem likely that this increased tension is also the cause of the higher rupture rate in the repaired FPL tendon compared to that of finger flexor tendon repairs. More recently, the presence of a retracted proximal end of the FPL tendon at surgery has been shown to be detrimental to the outcome of the tendon repair.2 Whether all FPL repairs, or only those with visible retraction of the proximal tendon at surgery, are exposed to increased tension as a result of the greater retraction of the FPL muscle remains unknown. Murphy believed this problem to be due to the fact that the FPL tendon is completely separated from the other flexor tendons, making retraction easier than where a tendon is restrained by others. An alternative explanation may lie in the difference of muscle configuration between the FPL muscle and those of the finger flexors.

The Avascular Zone 2 Site of The FPL

Recently, we re-examined data from our earlier studies and found that the rate of rupture after repair in zone 2 is twice as common as after zone 1 FPL repairs.3 Zone 1 FPL repairs had a rate of rupture similar to that of primary finger flexor repairs.4 The increased rate of rupture of zone 2 repairs largely explains the higher rupture rate of the FPL tendon when compared with finger flexor repairs in zones 1 and 2. A lack of extrinsic vascular supply of the FPL tendon immediately palmar to the metacarpophalangeal joint was identified by Lundborg.5 Hergenroeder et al6 also found that there is a zone of relative avascularity of the tendon at the same point, and this was illustrated by Tubiana et al.7 This avascular point coincides with the zone 2 site of FPL repair and may explain the particular susceptibility of zone 2 repairs to rupture, contributing to the higher rupture rate of FPL tendon primary repairs.

Treatment of FPL Division Before 1989

Reports published in the 20 years after Murphy’s report, when many repairs would now be classified as delayed primary, or even secondary surgery, repeatedly highlighted the difficulty of direct repair of the FPL after any delay and many recommended that primary repair be avoided in most instances.8 To overcome this problem, most authors favored tendon reconnection by interposition grafting,1,9–19 although some reported direct repairs of the tendon, usually in cases seen within a few hours.1,11,14–18,20–29 Tendon lengthening, either in the muscle or in the tendon at the wrist, was also used by several authors as an alternative to interposition grafting.12,15,26,30,31 During this era, all cases were immobilized postoperatively. Mobilization started at varying intervals from surgery, in one instance as early as 12 days after operation but usually after a longer delay of between 3 and 5 weeks. The results reported were often impressive. Unfortunately, direct comparison with today is difficult, if not impossible, as the methods of assessment differ, not only between different reports but also from all of the methods of assessment in current use. Although a few very large studies were reported, many contained very small numbers of cases, many being part of much larger studies of treatment of finger flexor tendon divisions. Rupture rates were rarely mentioned. In 1973, Urbaniak and Goldner reported their own experience32 and Urbaniak subsequently reviewed the options of treatment.33 Like others before him, Urbaniak favored direct repair when possible and used the other techniques when the tendon gap was too wide. The results of tendon lengthening in his unit were better than those of interposition grafting in those cases in which direct repair was not possible.

Treatment of FPL Division 1989–1999

Between the advent of primary direct repair and early postoperative mobilization of flexor tendons in the late 1950s and the end of the 20th century, there were surprisingly few reports published on the effectiveness of primary repair of the FPL tendon in zones 1 and 2, this being the common site of division of this tendon.34–37 These studies tended to confirm the high rupture rate after primary repair compared to primary repair of finger flexors. Various other studies of primary repair and early mobilization of finger flexor tendons included repairs of the FPL but usually in such small numbers and/or with inclusion of divisions of the FPL in other zones, as to make useful interpretation of the data difficult.38–43 Few of the units that reported large series of primary direct repairs of finger flexor tendons in zone 2 followed by early mobilization by any method have published equivalent results for the FPL tendon. Three studies of primary repair of the FPL tendon34,35,37 mobilized the repairs postoperatively in variations of the Kleinert technique of active extension-passive flexion mobilization.44 The fourth compared this regimen with immobilization of the repair for 4 weeks after surgery.36 Although Percival and Sykes reported an 8% rupture rate of 50 repairs,36 we used the work of these authors as a gold standard against which we compared our results at that time because a variety of problems with data presentation in the few other reports made direct comparison with our work difficult.

FPL Repair With 8% Ruptures: St. Andrew’s 1994–1999

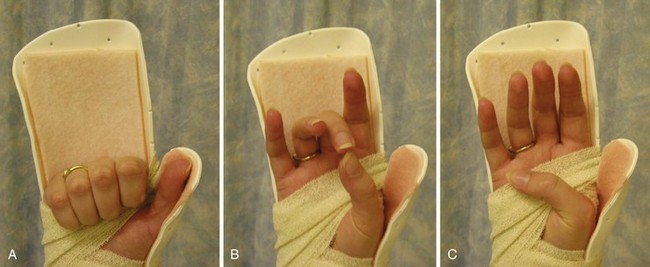

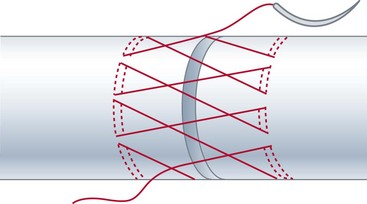

In an earlier report on primary repair of finger flexor tendons followed by early active mobilization, we included an assessment of 30 primary FPL repairs repaired with a two-strand modified Kessler suture and a simple running circumferential suture.45 These cases were mobilized in the manner used to mobilize finger flexor tendons but with the thumb only prevented from free movement and had a rupture rate of 17%. We recommended that early active mobilization using the technique we were using at that time was not appropriate to FPL tendon primary repair. Subsequently, we examined two additional groups of 39 and 49 patients with divided FPL tendons.8 In the first of these, the FPL tendons were repaired by the original method but mobilization was carried out in a modified splint, which included slight ulnar deviation of the wrist (intended to allow the FPL tendon a straighter “run” into the thumb) and inclusion of the fingers in the splint (Figure 16-1). The second group underwent a modified repair that included one of the more recent techniques of strengthening the circumferential repair46 (Figure 16-2) as well as mobilization in the modified splint. The changes in the splint alone made little difference to the rate of ruptures, only reducing the rupture rate to 15%. We retained the splint mainly because it included the fingers: power gripping with the fingers is almost automatically followed by movement of the thumb around the dorsum of the index and middle fingers, which brings the FPL into play and risks any primary FPL repair. Preventing normal finger activities remains part of our rehabilitation regimen. Despite achieving excellent and good results and a rupture rate equal to those in the Percival and Sykes study after addition of the stronger circumferential suture technique, the 8% rate of rupture in our study remained higher than the 4% to 5% reported from our unit for finger zone 1 and 2 primary flexor tendon repairs4 and was still a matter for concern. Although the drop of rupture rate from 17% to 8% was a definite improvement, the figures were not statistically significant; it would have required a study with 98 patients in each of the two groups for a reduction of this amount to attain a statistical significance of p <.05. This would have required a study period of 15 years, or longer. This presents a dilemma to clinicians reporting personal experiences in this field, even from busy units.

FPL Repair with No Ruptures: St. Andrew’s 1999–2004

The addition of a stronger core suture to the stronger epitendinous suture was the most obvious way of trying to further reduce the rupture rate of the FPL repair. In 2004, we reported another study in which a four-strand Kessler suture with a Silfverskiöld circumferential suture was used in the primary repair of 48 FPL tendons followed by early active mobilization.3 Two Kessler two-strand repairs in planes at 90° to each other were used (

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree