Secondary Reconstruction: Nipple–Areolar Reconstruction

Albert Losken

Introduction

Creation of the nipple–areolar complex often represents completion of postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Although this is considered a relatively minor procedure, its importance cannot be overstated. The nipple represents a natural break point in the breast and is a well-defined anatomic landmark contributing significantly to the final aesthetic outcome. Nipple reconstruction will often transform a nondescript mound into a breast, highlighting both shape and symmetry. Despite potential loss of projection and the fact that nipple function (erogenous sensation and lactation) is not preserved, the majority of women still choose to reconstruct the nipple–areolar complex, further emphasizing the importance of this procedure. Patients feel better with their breast reconstruction following completion of nipple reconstruction, and studies have demonstrated greater patient and partner satisfaction with nipple reconstruction (1,2,3). Many different options exist when it comes to technique that is probably testament to the fact that we are yet to identify the ideal method of nipple reconstruction. The technique chosen needs to be reliable, easy to perform, and versatile, with sufficient long-term projection.

Nipple reconstruction is essentially indicated whenever there is an absence of the nipple due to congenital reasons, or more commonly following mastectomy for the treatment of breast cancer. Since it is a minor procedure that can be performed under local anesthesia, there are really no absolute medical contraindications; however, it does require reconstruction of a breast mound with reasonable shape and symmetry with the opposite side before attempting to reconstruct the nipple. The main reason why nipple reconstruction would not be performed is related to patient choice. Some patients will chose to defer nipple reconstruction for various reasons.

Appropriate preoperative planning is crucial. Many variables need to be taken into consideration prior to reconstruction of the nipple. Incorrect placement of the new nipple no matter how good the actual nipple looks results in an unfavorable outcome. Patient desires and expectations need to be discussed. Important anatomic considerations include the position of the nipple on the breast, size, color, texture, and areola shape.

Timing

Immediate nipple reconstruction at the time of formal breast reconstruction is possible in select situations (4,5). Women with relatively small, nonptotic breast who undergo a skin-sparing or areola-sparing mastectomy and autologous reconstruction and do not require adjustment of the opposite breast are reasonable candidates for immediate nipple reconstruction. Other situations when immediate nipple reconstruction is reasonable include bilateral autologous breast reconstruction when nipple position is easily determined and reproduced at the time of reconstruction. However, since the position of the reconstructed breast mound is often unpredictable, the vast majority of nipples are reconstructed secondarily once the final shape has been established. This is often approximately 3 months following the reconstruction; however, it is delayed longer in the setting of adjuvant therapy. Another reason for performing nipple reconstruction at a secondary stage is that the patient is then able to participate in deciding on the most appropriate nipple position.

Additional Procedures

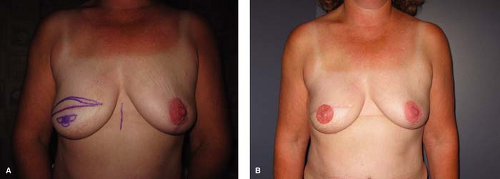

Nipple reconstruction is often performed once the final shape and symmetry has been achieved. It is reasonable to perform nipple reconstruction with minor adjustments in shape and size made to the reconstructed breast (Fig. 33.1). Minor adjustments to the contralateral breast also make it possible to predict desired nipple position on the reconstructed breast. However, whenever major revisions are required to improve symmetry and shape or when adjustments are required on both sides, it becomes preferable to defer nipple reconstruction.

Nipple Position

Although we often have little control over the potential for loss of nipple projection, appropriate positioning of the reconstructed nipple is arguably even more important

and is something that is completely within our control. A poorly positioned nipple, even if it has the best shape and projection, is considered a failure and significantly affects final shape and symmetry. Secondary correction of position is often difficult and with expander reconstruction essentially requires removal and reconstruction in a different location if possible. The nipple–areolar complex position can be adjusted primarily or secondarily similar to a mastopexy-type technique when a skin island is present following skin-sparing mastectomy (Fig. 33.2).

and is something that is completely within our control. A poorly positioned nipple, even if it has the best shape and projection, is considered a failure and significantly affects final shape and symmetry. Secondary correction of position is often difficult and with expander reconstruction essentially requires removal and reconstruction in a different location if possible. The nipple–areolar complex position can be adjusted primarily or secondarily similar to a mastopexy-type technique when a skin island is present following skin-sparing mastectomy (Fig. 33.2).

Anatomy

The normal nipple position is approximately 19 to 21 cm from the sternal notch or midclavicular line. Other measurements include approximately 9 to 11 cm from the midpoint of the sternum and 8 cm from the nipple to the inframammary fold. Areola diameter varies; however, it is typically in the range of 42 to 45 cm.

Marking

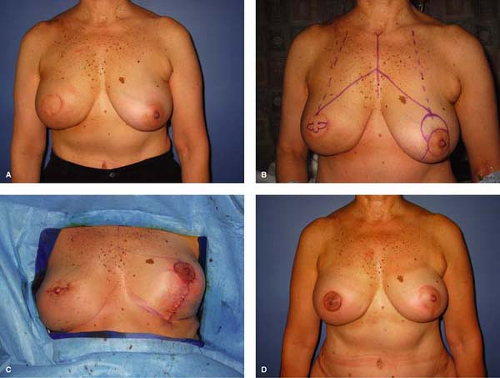

Nipple position is determined preoperatively with the patient in the standing position. When the skin island following skin-sparing mastectomy and autologous reconstructions is aesthetically located on the breast mound, the nipple position is typically marked in the center of the skin island. Implant reconstruction and delayed reconstruction will often require more measurements and calculation. Unilateral reconstruction requires matching the reconstructed nipple with the contralateral nipple position. This is easiest when the breast mounds are fairly symmetric and the opposite nipple is appropriately positioned on the breast mound. It is more challenging when adjustments to the contralateral breast mound are indicated and the new nipple position needs to be anticipated on the basis of the proposed position of the contralateral nipple following adjustment (Fig. 33.3). It is important to measure the position with two coordinates (Fig. 33.4). The midline of the chest is marked, and the distance from the contralateral nipple to the midline is measured and recreated on the reconstructed side. A second measurement from higher up on the midline or from the sternal notch to the nipple is also measured and confirmed on the opposite side before finalizing proposed position. A triangle is essentially created with two equal measurements on each side. The ideal nipple position following bilateral reconstructions is often determined on the basis of the shape of the breast mound and breast meridian. Placing the nipple too medial or too high is a mistake. Patient input is often helpful; round stickers can be placed temporarily and easily repositioned to determine appropriate position.

Figure 33.4 Nipple position is typically marked and measured on two axis points: one from the sternal notch and another from the midline at the level of the nipple. |

Once the nipple position has been determined and marked with a circle, the type of flap design is drawn out. The flap markings are adjusted depending on the size and shape of the contralateral nipple.

Technique

Although numerous techniques have been described, the two basic methods include local flaps and a composite graft.

Local Flaps

Local flaps are more popular since women are often hesitant to interfere with the opposite normal nipple. Local flaps are essentially all variants of the same principle, whereby random flaps are designed relying on the subdermal plexus, and wrapped in unique designs to create projection. Some of the techniques include the quadrapod flap, skate flap, dermal fat flap, double-opposing–tab flap, S flap, Anton–Hartrampf star flap, C-V flap, and the T and H flaps (6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14). Choice of technique is mainly determined by surgeon preference and comfort. Evidence-based comparisons in the literature are sparse, making claims of one techniques superiority to others difficult (15). One expected outcome that all local flap techniques have in common is loss of nipple projection. Although this is difficult to quantify, on average, a 50% reduction can be expected usually within the first few months. Modifications are continually being performed in an attempt to improve long-term projection.

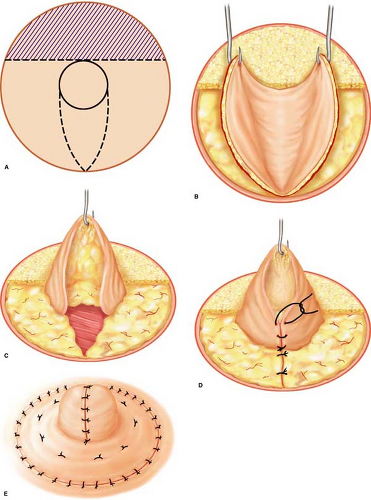

The skate flap is another local flap option that is designed on the future areola base leaving an area that typically requires a skin graft for coverage. Once nipple position is determined, the axis for the skate flap is designed by drawing a line tangential to the nipple base. This axis should be rotated to avoid including the mastectomy scar within the wings or body of the skate flap. The length of this base tangent is approximately three times the diameter of the nipple circle. The height of the body is approximately twice the height of the opposite nipple erect. Curved lines are then drawn between the ends of the base tangent to the apex of the flap. The ellipsoid margins are incised, raising the two wings starting thin and becoming thicker. The central third of the base tangent is not incised to maximize flap perfusion. The wings of the skate flap receive their blood supply from intradermal vessels and the central pedicle. When the base is reached, the remaining wedge of skin is elevated with underlying subcutaneous tissue equivalent to the nipple’s diameter. The central pedicle is raised and wrapped with the lateral wings to create the nipple. The pointed tip configuration can be avoided by amputating the tip distally and closing it primarily or in a purse-string manner. The donor site is either closed primarily or covered with a full-thickness skin graft harvested from the groin or other suitable area (Fig. 33.5).

The C-V flap is an evolution of the skate flap and is the author’s preferred technique. It is a simple technique that essentially involves one C-flap and two V-flaps. The position of the desired nipple is marked with a circle. Two horizontal lines are marked on either side of the circle (Fig. 33.6). These parallel lines are usually approximately a centimeter apart and would result in 1 cm of projection. The width of these flaps determines the projection. The upper line is longer to create the V-portion that allows primary closure without contour distortion. The C-flap is then marked inferiorly (if a superiorly based flap is chosen). The C-flap donor site creates a circular base for insetting the V-flaps. The diameter of the C-flap will be similar to that of the final nipple diameter. It is important not to make this half circle too wide or too large since this will flatten the nipple. The pedicle is kept approximately a centimeter wide. It is important to maximize the blood supply by preserving the subcutaneous tissues and subdermal plexus at the level of the pedicle. Adjustments are made to the markings depending on the size of the contralateral nipple. However, most of the time, the nipple is made as large as possible and twice as big as the opposite nipple to allow for anticipated loss of projection. The flaps are then infiltrated with lidocaine and epinephrine. The incisions are made full thickness with a 15C blade. The V-flaps are elevated with some subcutaneous fat. The C-flap is elevated and the flap is back-cut toward the pedicle only

as much as is required to lift the nipple up 90 degrees unrestricted. Since the dermis is often thicker following latissimus dorsi reconstruction, the skin flaps are kept thinner than usual. After minimal undermining if necessary, the V-flap donor site is closed with resorbable sutures. The tips of the V-flaps are then trimmed square to maintain the even 1-cm height. The flaps are wrapped around and sutured inferiorly at the 6 o’clock position to the middle of the C-flap donor site, which serves as a nipple defining stitch. The C-flap is then placed on top as a cap.

as much as is required to lift the nipple up 90 degrees unrestricted. Since the dermis is often thicker following latissimus dorsi reconstruction, the skin flaps are kept thinner than usual. After minimal undermining if necessary, the V-flap donor site is closed with resorbable sutures. The tips of the V-flaps are then trimmed square to maintain the even 1-cm height. The flaps are wrapped around and sutured inferiorly at the 6 o’clock position to the middle of the C-flap donor site, which serves as a nipple defining stitch. The C-flap is then placed on top as a cap.

Figure 33.5 Illustration of the skate flap being drawn and raised. A. Preoperative markings. B–C.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|