29 Secondary deformities of the cleft lip, nose, and palate

Introduction

The etiology of secondary cleft deformities is multifactorial. The most influential factors leading to the development of a secondary deformity are the type and severity of the cleft, as well as the primary repair technique. Poor preoperative analysis and choice of technique will always lead to a secondary deformity. Matching the deformity to procedure takes a great deal of experience and flexibility by the surgeon. This experience and level of attention to detail can greatly affect results and the need for secondary correction. Tips and tricks learned by a single surgeon over a lifetime of performing cleft surgery can never truly be conveyed verbally or on paper. Lastly, because essentially all patients are operated on within the first year of life, the long period of dramatic growth and the resultant scar after the repair of the cleft structures both profoundly affect the end result. Delaying the definitive repair until a child has reached adolescence or adulthood may minimize the bony growth disturbance; however, early repair of the cleft deformity is mandatory for functional development and psychosocial benefit. Unrestrained growth of the cleft margins may result in even more severe secondary deformities, as the repaired structures guide growth in an anatomic fashion. It is ideal to allow the facial structures to develop in a normal relationship to one another in the intended “functional matrix.” Interestingly, this debate may become less important, as we learn more about whether these growth disturbances actually result from surgical insult or are simply sequelae of an intrinsic bony genetic defect. Correction of the unilateral cleft lip deformity was once thought to restrict the growth of the midface; however, based upon more recent animal studies, the hypoplasia may be secondary to an intrinsic growth deficit.1–3

Basic science/disease process

Wound healing and growth

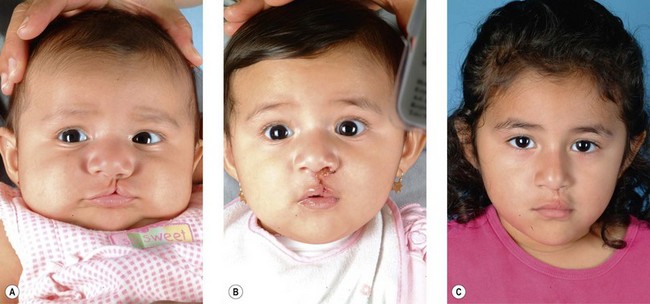

Secondary deformities occur for a number of reasons, including scarring, physical growth, and in some cases, technical error with the primary repair. Scarring affects individuals to varying degrees, and whether related to genetics or ethnic heritage, it can have profound results on aesthetic outcomes. The scar contraction can distort the fragile anatomic landmarks of the lip and nose, while excess scar tissue deposition can lead to unsightly irregularities in contour and color. Additionally, physical growth is often referred to as the “fourth dimension” in cleft lip and palate surgery. The growth of the osseocartilaginous skeleton and soft tissues of the face is difficult to predict, and can very visibly affect outcomes. The original cleft lip surgery occurs months after birth with careful approximation and alignment of landmarks and facial structures in three dimensions; however, the human face undergoes rapid periods of growth from birth to 5 years of age and also during puberty, with final osseocartilaginous facial growth in normal children ending with the cessation of puberty. The subsequent changes in aesthetic outcomes that this “fourth dimension” will have are difficult to predict. Finally, technical error or poor technique selection can play a role in outcomes. Together, these factors allow secondary deformities of the cleft lip and palate to be the rule, and not the exception (Figs 29.1, 29.2).

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Secondary deformity management is an integral part of treating the cleft lip and/or palate deformity. Patients with cleft lip and palate will undergo, on average, at least one nose and lip revision when followed into adolescence, with a significant number of individuals requiring multiple interventions.4–6

The reported incidence rates of palatal fistulas have varied greatly, with citations ranging from 0 to 76%; however, caution should be used when interpreting this data as definitions vary and asymptomatic fistulas are often excluded. Interestingly, over the past 5 years, reported palatal fistula rates have decreased. Using a variety of surgical techniques, authors report fistula rates between 0 and 12.9%, with 0–8.1% being symptomatic.7–19

Several studies have looked at the rates of fistula formation, and several strong factors have been identified. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated that surgeon experience is a major predictor of postoperative fistula rates.7,20,21 Murthy et al. reviewed one surgeon’s lifetime experience and noted that over 80% of his palatal fistulas occurred in the first 10 years of practice.7 Additionally, Cohen et al. reported on three independently functioning surgeons: two had performed over 45 cleft palate repairs each and had fistula rates of 15% and 18%, while the third surgeon performed only 19 cleft palate repairs, and reported fistula rates of 63%.21

Studies have also demonstrated that the width of the initial palatal defect, the width of the palatal shelves, and ratio of the cleft width to the posterior arch width were significant predictors of palatal fistulas postoperatively.21 Finally, other risk factors continue to be debated, including initial Veau classification of the defect, type of closure, age at repair, and gender.

Fistulas, regardless of size, represent a complex problem, as they are indicative of a significant scarring along a tense palatal closure. This is demonstrated by relatively high recurrence rates reported historically following fistula repair (25–100%)11,21,22–31; however, more recent data have demonstrated that fistula recurrence rates of 0–25%7,11,23–25 are now being achieved.

Underlying each cleft lip and/or palate is a variable degree of skeletal deformity and hypoplasia. In a portion of these cases, the deficiency is mild and can be treated with orthodontics alone. On the other hand, for unilateral clefts, the reported incidence of orthognathic surgery varies between 26% and 48.5%, and for bilateral clefts is 24–76.5%.21,26,27 The need ultimately varies based on threshold for performing orthognathic surgery.

Cleft lip

Normal lip anatomy

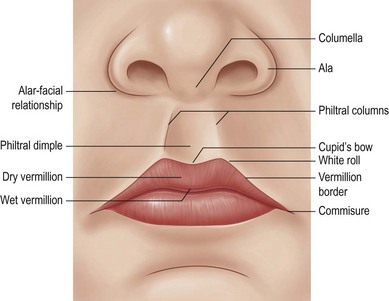

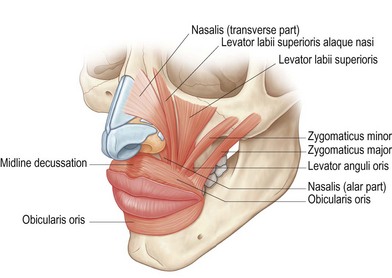

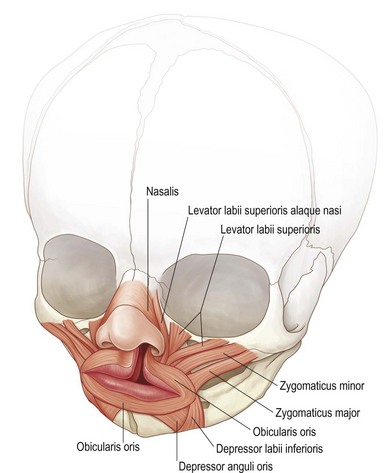

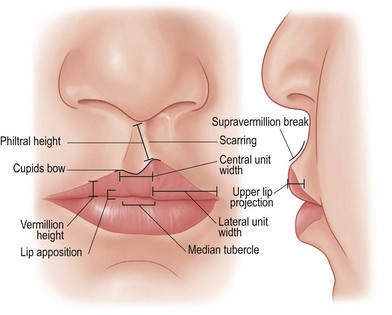

The lips’ surface can be divided into three portions: cutaneous, dry vermillion, and wet vermillion (Fig. 29.3). Immediately underlying these superficial layers is a thin layer of connective tissue and fat, followed by a group of muscles which give the upper lip many of its structural and functional features (Fig. 29.4). Other important aesthetic features include the contour and volume of the lips, provided by soft-tissue bulk and configuration.28–31 Finally, the upper gingivobuccal sulcus plays an important role in the appearance and movement of the lip with animation.

Cleft lip anatomy

In the cleft lip, the anatomy is both disrupted and diminutive.32 In general, the changes can be understood by dividing the discussion into the topics of: landmarks (philtral columns, white roll, cupid’s bow), vermillion, and muscular continuity (Fig. 29.5).

Evaluation

It is useful to determine, either through medical records and/or clinical assessment, the type of primary repair and if any secondary procedures have been performed. When evaluating secondary deformities, it is helpful to have a conceptual framework in place to evaluate the lip in a systematic matter. Objective methods have been described to evaluate secondary deformities33,34; however, in day-to-day practice, these can be quite cumbersome. It helps, though, to take the essential elements from these to categorize deformities into five broad areas: scarring, lip, vermillion, muscle, and buccal sulcus.

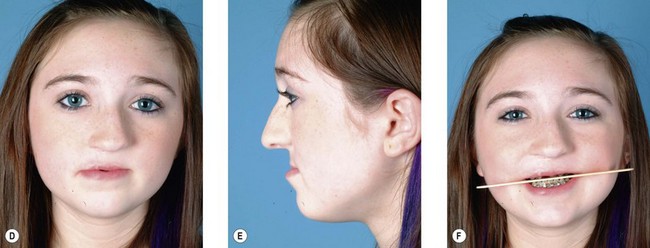

Any of the previously mentioned deformities can occur concomitantly, and as such, require the surgeon to prioritize treatment based on the importance and realistic potential benefit to the patient. The ultimate goal is a surgical plan that yields the best result, in the fewest number of operations (Fig. 29.6).

Patient selection

Scarring

While the corrected cleft lip deformity often looks its best at the first office visit, the process of scar maturation can result in significant color and contour abnormalities, distortion of adjacent mobile landmarks, and shortening of the lip dimensions. While these changes may necessitate a secondary correction, there are actions that can be taken during the healing process to minimize the severity of its sequelae. Parents should be advised to massage the scar with the lotion of their choice (vitamin E, cocoa butter, zinc, or Mederma), and utilize sun protection for at least 1 year to prevent persistent hyperpigmentation. These acute interventions are beneficial, not only for scar improvement, but also psychologically, as they involve the family in the care of the child. While silicone sheeting and hypoallergenic taping may be beneficial in the treatment of scars,36 they may be difficult to maintain on the upper lip of a child and therefore yield varying results. Intralesional steroid injections may be started if there is evidence of hypertrophic or keloid scarring, or if the patient is at high risk for either of these. If the scar continues to be problematic after optimal conservative care, and a minimum of 12–18 months has been allowed for scar maturation, consideration should be given to a surgical revision.

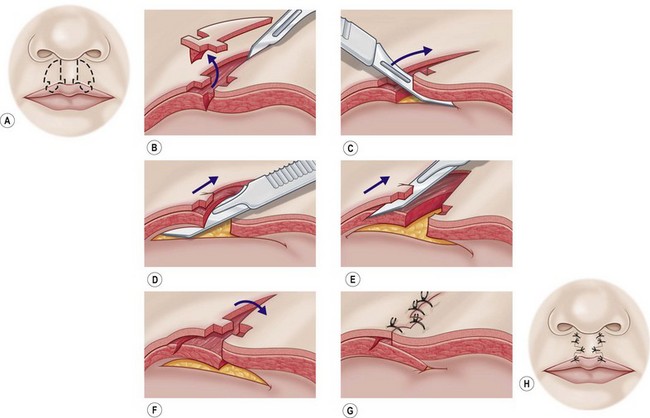

Several surgical options exist for the treatment of secondary cleft lip scarring. The appropriate treatment selection should take into consideration the characteristics of the scar. Dermabrasion is a potential option for scars that are elevated. If scars are hypertrophic and have widened significantly, treatment with excision in the shape of a diamond or ellipse facilitates a straight-line closure. If the scar is depressed or overlies a philtral column a skin-only excision with a vest-over-pants closure (Fig. 29.7), or other bulking techniques (see philtral column distortion section, below) will be helpful.

Lip

Short lip

The difference in lip height between normal and repaired sides is precisely measured to determine the amount of lengthening necessary. In patients with minor deformities (<2–3 mm), the shortness may be treated by a diamond-shaped scar excision or a unilimb Z-plasty to lengthen the philtrum; however, for lip shortening greater than 2–3 mm, these techniques may be insufficient. For this degree of lip shortening, one option is to perform a standard Z-plasty to lengthen the philtral column; however, it is important to remember that this technique places additional scars on the upper lip. For more significant degrees of shortening, or if additional scars from a Z-plasty are not preferable, the entire repair should be taken down and repeated (Fig. 29.8).

Tight lip

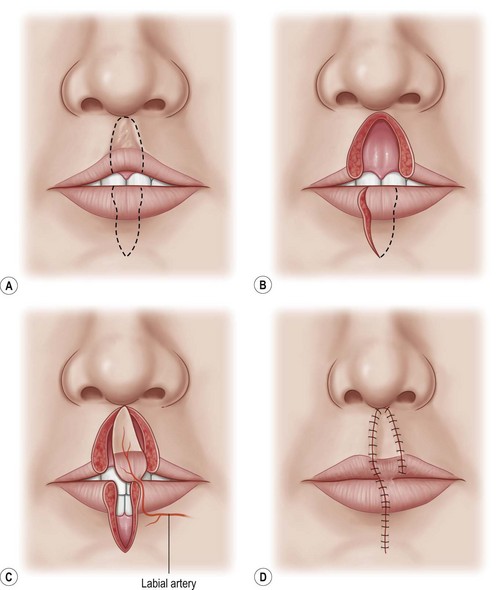

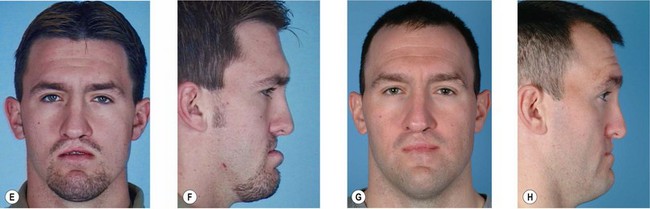

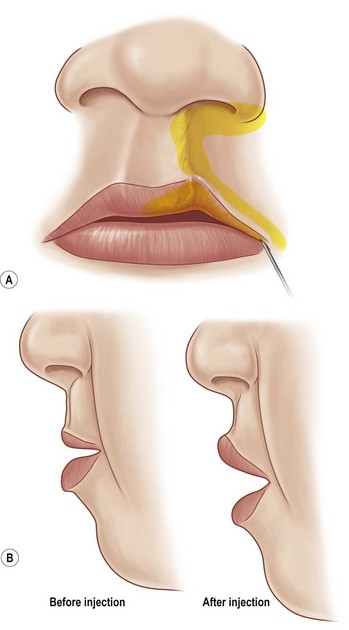

The Abbé flap transfers full-thickness lip elements to the upper lip in a two-stage procedure by transfer of a lower lip segment based on the inferior labial vessels. The pedicled flap is then left in place for 2–3 weeks, before division and inset (Fig. 29.9). While this flap is more commonly used with secondary bilateral cleft lip deformities, it can be used when there is: (1) decreased anteroposterior projection of the upper lip (particularly helpful in reducing the disparity in tissue volume between the upper and lower lip); (2) excess scarring of the central aesthetic unit; and (3) a significantly narrowed or shortened central aesthetic unit. Additionally, the flap provides a pseudodimple for the philtrum, a tuft of hair in males, and continuity of surface landmarks (Fig. 29.10). This procedure, however, should not be the first choice, because of donor site morbidity, increased risk associated with two procedures, and patient discomfort associated with a 2–3-week period of flap delay between stages.

Philtral column distortion

The philtral column can be affected by excessive scarring, short length, or a lack of prominence. In the case of excess scarring, the methods described in the section on scarring, above, can improve aesthetic outcomes. Shortened philtral columns can be addressed using methods described in the section on vermillion notching, below. Methods to recreate the philtral column, in general, involve either the addition or overlapping of soft tissue to add soft-tissue elevation. Fat grafts (free or dermal) have been used by some to augment the philtral column (Fig. 29.11), and a “vest-over-pants” closure is an option to create the philtral column using local tissues. The latter method involves excision of the prior scar, with subsequent burial of the underlying dermis underneath the adjacent dermis to provide the bulk for the philtral column. Additional methods have been described, including using mattress sutures to reapproximate and evert the orbicularis, as well as vertical interdigitation of the orbicularis.37

Vermillion

Thin lip

The goals for treating a thin lip deformity are to increase the amount of vermillion show, improve anteroposterior projection of the upper lip, and replace contour landmarks (the break point existing 3–4 mm above the upper lip vermillion and the prominent median tubercle). These goals are even more important in the female population, as increased vermillion show and volume are associated with increased attractiveness.29,30 In cases of patients with adequate vermillion but a paucity of volume, fat grafting becomes an excellent option. This can be performed with either free fat injections or via a dermal fat graft.

Free fat grafting can be performed by harvesting adipose tissue from the lateral thigh or the periumbilical region, processing the fat, and subsequently injecting this into the upper lip via small stab incisions, just medial to the oral commissures (Figs 29.11 and 29.12). In addition to increasing volume, there is much recent interest and reports of fat grafting improving the quality and color of overlying skin in scarred or radiated beds. While the procedure is simple in nature, it can become difficult if there is a significant amount of scar, making tunneling and multiple small-volume passes difficult. The authors have had more success fat grafting unscarred beds, as expanding the contracted, tight scar is quite challenging even with repeated injections.