Key Words

cleft lip, cleft secondary deformity, cleft lip under-rotation, cleft rhinoplasty, vermilio-cutaneous notch

Synopsis

Primary cleft lips are congenital and result from a failure of the medial nasal prominence of the frontonasal process to join with the maxillary process during embryogenesis. Variability in primary cleft lip defects consists of a spectrum based on their severity, such as complete/incomplete, the width of the cleft, and the alignment of the medial and lateral segments. In primary cleft lips, multiple surgical techniques and methods exist specifically to address the deformity and achieve the goal of symmetrical labial and nasal anatomy and are generally performed before 6 months of age. However, unlike primary cleft deformities, secondary cleft deformities have varied etiologies: they can result from persistent residual deformities, develop over time during facial growth, or form as a sequelae of primary repair techniques. Secondary cleft deformities include (but are not limited to) a too-short or too-long white lip, misalignment of vermilio-cutaneous junctions, or abnormal contour of the free mucosal border. Because secondary deformities are more variable than the primary cleft deformities, both in etiology and presentation, secondary corrective procedures need to be individualized to address the specific deformity for each patient. As such, the goal of secondary cleft lip procedures is to redress specific cleft stigmata that are either residual from the initial surgery or have arisen over time. Secondary deformities can be corrected through application of general plastic surgery principles and techniques. Pre-operative examination of the issue and attentiveness to the timing of the procedure are crucial to a successful secondary repair, though prevention of secondary deformities arising from primary repair should remain paramount. Lastly, it is important to note that because many of these secondary deformities can appear concomitantly in a patient, one must prioritize treatment that will provide the best result to the patient, and utilizing the fewest number of operations.

Clinical Problem and Principles of Treatment

Clinical problems of secondary cleft lip reconstruction are rooted in stigmata that arise after primary cleft lip surgery. Recognizing the various deformities allows one to be better informed in enacting pre-operative care and planning the course of action for subsequent procedures. This section attempts to cover the most commonly recognizable deformities, which can be sorted into five basic categories: general scarring, white lip, vermilion and mucosa, muscle, and buccal sulcus. The principal stigmata in unilateral clefts are usually related to asymmetry, whereas the stigmata in bilateral clefts are related to disproportion of repaired elements to the face. Both unilateral and bilateral clefts can have distortions based on deeper soft tissue elements such as muscle and mucosa.

The following section will be organized by discussing commonly seen stigmata as well as common procedures to rectify them. From an operative perspective, one major difference between primary and secondary cleft lip repair is that whereas the former case employs tailored cleft lip repairs with the aim of properly orienting lip and nasal elements, the latter case uses general plastic surgery principles and techniques to achieve its goal. To reiterate, secondary cleft lip procedures aim to fix stigmata that have either arisen from the initial procedure or have arisen with time. Thus for an in-depth discussion of cleft lip repair techniques, please refer to the chapters on primary cleft lip repair ( Chapters 3.1 and 3.2 ).

General Scarring

Scarring from the previous surgical intervention(s) should be examined for signs of immaturity, contour changes, and distortion of local structures because worsening scarring may require acute intervention, whereas improving scars should be carefully monitored until they mature. Scarring along the philtral ridge on the cleft side may be thick and prominent. Scars are still considered immature within 1 year of the primary repair, and during this time, scar massage is recommended.

Occasionally, for a very firm and raised hypertrophic scar, injection with triamcinolone is acceptable and can usually be done during cleft palate repair. However, due to the child’s age, the injection may not be given without general anesthesia. Persistent incisional hypertrophic scars nonresponsive to massage or triamcinolone injections should be excised and reclosed.

Short and Long Lip (Unilateral Cleft)

Short and long lip are usually asymmetries seen compared with the normal half of the lip and are stigmata of unilateral clefts, occurring when the repair is not matched to the normal side. A short lip is recognized by having a philtral column on the cleft side that is at least 3 mm shorter than the contralateral non-cleft side, whereas a philtral column that is longer vertically on the cleft side compared with the non-cleft side is characteristic of a long lip. Active underlying scar contracture (that improves over time) may be responsible for producing a minor short lip, whereas more severe cases are usually the result of an improperly designed rotation advancement lip repair. A long lip stigma resulting from a rotation advancement repair is much rarer and is more frequently associated with the Tennison repair.

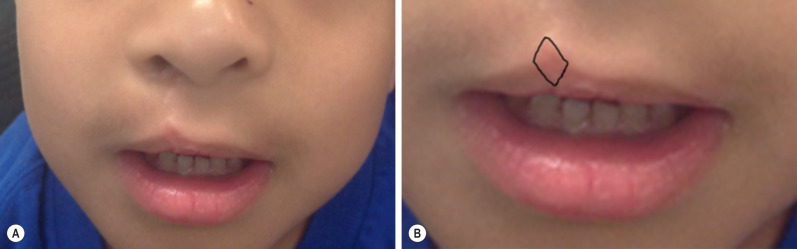

Short lip deformities are usually associated with the rotation-advancement repair of Millard and similar techniques. A very minimally shortened white lip on the cleft side can be attributable to superficial scar contracture during wound healing, worst at 6 to 12 weeks after primary repair, and will eventually resolve and can be improved with active massaging. In the case of a minor short lip deformity (<3 mm), a diamond-shaped scar excision is sufficient in augmenting the lip 2 to 3 mm ( Fig. 3.3.1 ). For short lip deformities that are greater than 3 mm, Z-plasties along the philtral column of the cleft side can lengthen the white lip length. However, oblique and horizontal scars out of line with the philtral column may result. Severe mismatch may be a result of technical error from the primary repair ( Fig. 3.3.2 ), and will require complete takedown and re-rotation and advancement of the cleft lip.

Long lip stigmata have become increasingly rare due to a reduction in the usage of the Tennison repair in favor of the Millard rotation-advancement technique in primary cleft lip repairs. Nonetheless, in the case of a long lip deformity, multiple studies have shown that superficially excising tissue from the alar base in an effort to elevate the cleft side is insufficient in redressing the issue. The use of permanent suspension sutures to the periosteum to aid in long lip repair also has mixed results. Thus it is recommended to take down the entire repair and to excise tissue from all dimensions to fully fix the stigma.

In bilateral clefts, an overly long and overly wide philtrum will appear disproportionate to the face and is not primarily from asymmetry from left to right side and will be addressed in a later section.

Tight and Wide Lip (Bilateral Clefts)

An overly long and overly wide philtrum may result because those nasolabial elements are fast-growing, potentially causing the stigmata to worsen as the child grows ( Fig. 3.3.3A ). The best way to prevent these stigmata is to perform a primary repair that intentionally minimizes the philtral flap dimensions. This correction can be achieved by marking a shorter and narrower philtral flap within the philtrum, then re-raising the smaller philtral flap while discarding the rest of the oversized philtral skin ( Fig. 3.3.3B ). The medial tubercle is then divided, and the lateral lip elements are re-advanced and raised to meet the new philtral flap. The underlying muscles and mucosa may need to be re-approximated as well.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree