9 Secondary blepharoplasty

Techniques

Synopsis

Serious complications of primary blepharoplasty surgery are rare, but should they occur, can be difficult to correct and be potentially disastrous.

Serious complications of primary blepharoplasty surgery are rare, but should they occur, can be difficult to correct and be potentially disastrous.

Some serious complications which develop early, such as corneal exposure, require aggressive treatment, but lesser complications such as minor lid malpositions should be dealt with after time has passed to allow for scar maturation.

Some serious complications which develop early, such as corneal exposure, require aggressive treatment, but lesser complications such as minor lid malpositions should be dealt with after time has passed to allow for scar maturation.

The eyelids can be divided into four anatomic zones.

The eyelids can be divided into four anatomic zones.

Upper eyelid problems include ptosis and lid retraction. An understanding of Herring’s law is necessary to diagnose the problem responsible for lid level asymmetry.

Upper eyelid problems include ptosis and lid retraction. An understanding of Herring’s law is necessary to diagnose the problem responsible for lid level asymmetry.

Lower lid malposition is a common problem after primary blepharoplasty, and is due to an interplay between the patient’s unique orbital and eyelid anatomy, and the cicatricial forces. There are a number of predisposing factors.

Lower lid malposition is a common problem after primary blepharoplasty, and is due to an interplay between the patient’s unique orbital and eyelid anatomy, and the cicatricial forces. There are a number of predisposing factors.

Lower lid evaluation should address the presence of cicatricial contraction, a vector analysis of the globe in relation to the malar eminence, a soft tissue to bone distance at the lateral canthus, tarsoligamentous integrity (distraction and snap tests), lower lid eversion, and the level of the malar fat pad.

Lower lid evaluation should address the presence of cicatricial contraction, a vector analysis of the globe in relation to the malar eminence, a soft tissue to bone distance at the lateral canthus, tarsoligamentous integrity (distraction and snap tests), lower lid eversion, and the level of the malar fat pad.

Lower lid malposition can be treated with various methods, including a wide variety of canthopexy and canthoplasty procedures, vertical spacer grafts and midface elevation. In severe cases, a combination of modalities is often indicated.

Lower lid malposition can be treated with various methods, including a wide variety of canthopexy and canthoplasty procedures, vertical spacer grafts and midface elevation. In severe cases, a combination of modalities is often indicated.

Introduction

Each year, over 200 000 people in the United States have a blepharoplasty operation.1 These operations are generally very successful with a high level of patient satisfaction. Successful operations are the result of thorough preoperative evaluation, skillfully performed customized surgical procedures, uneventful anesthesia, proper surgical venue and individualized postoperative management. Although rare, complications and unfavorable results may occur following blepharoplasty. It has been estimated that the complication rate following blepharoplasty is 2%.2–21 Minor complications are temporary and self-limiting with minimal visual disturbance or aesthetic consequence (Table 9.1). Major complications are definitely undesirable and potentially disastrous. They include visual loss, fixed eyelid deformities, corneal decomposition, and significant aesthetic compromise (Table 9.2). In addition, an apparent technically successful operation may produce a very unhappy patient.

Table 9.1 Minor blepharoplasty complications

From Jelks GW, Jelks EB. Blepharoplasty. In: Peck GC, ed. Complications and problems in aesthetic plastic surgery. New York: Gower Medical Publishing; 1992.27

Table 9.2 Major blepharoplasty complications

From Jelks GW, Jelks EB. Blepharoplasty. In: Peck GC, ed. Complications and problems in aesthetic plastic surgery. New York: Gower Medical Publishing; 1992.27

The easiest complication to avoid is failure to recognize a pre-existing condition that would increase the likelihood of an unfavorable result from standard blepharoplasty (Table 9.3).22–25 The pre-existing conditions include: (1) medical or ophthalmological conditions that may increase the risk of visual impairment; (2) morphological variants that predispose the patient to post-blepharoplasty eyelid malpositions; (3) anatomical variations that may be accentuated after eyelid skin, muscle; and fat removal and, most importantly, (4) the psychological status of the patient and assessment of their expectations of surgery. The presence of a pre-existing condition does not preclude cosmetic blepharoplasty; however, the surgical timing, venue, and technique may have to be altered.

Table 9.3 Prevention of blepharoplasty complications: preoperative evaluation

Anatomical zones

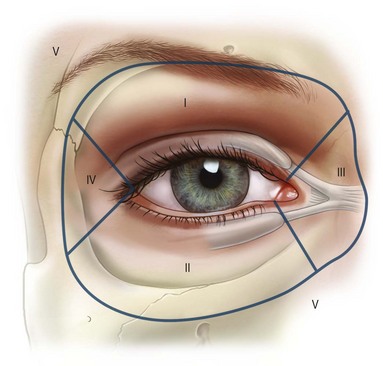

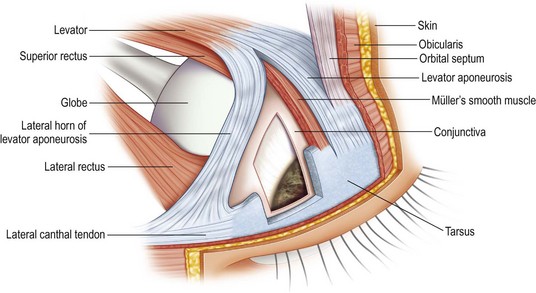

To facilitate complete and thorough anatomical analysis, the eyelids are divided into zones (Fig. 9.1).22,26 Zone 0 includes the ocular globe and orbital structures behind the arcus marginalis, posterior lacrimal crest, and lateral retinaculum. Zones I and II include the upper eyelid and lower eyelid, respectively, from the lateral commissure to the temporal aspect of canalicular puncti. Zone III is the medial canthus with the lacrimal drainage system. Zone IV is the lateral retinaculum. Zones I–IV are further subdivided into structures that are anterior (preseptal) or posterior (postseptal) to the orbital septum. Zone V includes the contiguous periorbital structures of nasal, glabella, brow, forehead, temple, malar, and nasojugal regions which merge with zones I–IV (Fig. 9.2). The diagnosis and management of upper eyelid (zone I) and lower eyelid (zone II) complications that occur as a result of blepharoplasty procedures will be discussed in detail.

Corneal protection

In both primary and secondary surgery of the eyelids and orbital region, protection of the cornea is essential. Specially designed, protective contact lenses should be routine (Fig. 9.3).27 Colored lenses are preferred as they filter bright operating light if the procedure is performed under local anesthesia, and they are also less often inadvertently left on the cornea postoperatively. The contact shell prevents desiccation and inadvertent corneal injury by an instrument or gauze. In order to avoid postoperative corneal abrasions, deep sutures on or near the conjunctival surface should be placed in such a manner that the knots are buried in the tissue or placed externally. A continuous buried suture that may be pulled out after healing is particularly useful in the approximation of tissue over the cornea. Skin grafts should not be placed in the conjunctival sac if they are to be in contact with the cornea; only conjunctival or other mucosal tissue is tolerated by the cornea.

Upper eyelid

Upper eyelid malposition: evaluation and management

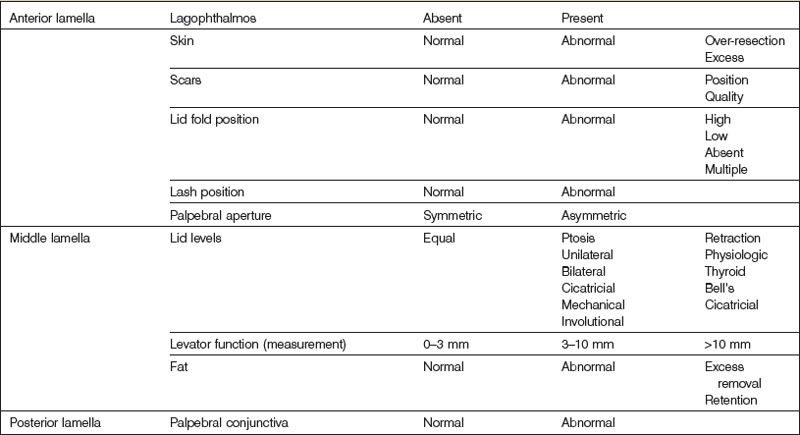

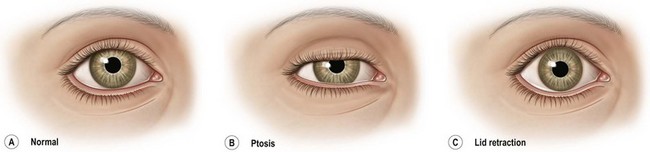

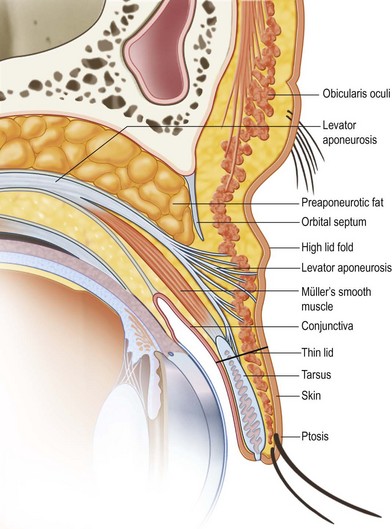

A thorough evaluation of the upper eyelid (zone I) level is facilitated by dividing the structure into anterior, middle, and posterior lamella (Table 9.4). The anterior lamella is composed of upper lid skin and orbicularis muscle. The middle lamella is composed of the tarsus, levator mechanism, orbital septum, and fat. The posterior lamella consists of the conjunctiva. The palpebral aperture is primarily influenced by the upper eyelid levels (Fig. 9.4). The palpebral aperture usually varies in shape, size, and obliquity due to hereditary, racial, traumatic, or other acquired situations. The surrounding bony orbital anatomy, the internal orbital volume, and the integrity of the eyelids, with their muscular and tarsoligamentous supports, are some of the factors that influence the palpebral aperture (Figs 9.5, 9.6). It is also influenced by the relative amount of associated periorbital skin, fat, and soft tissues. Unique individual combinations of eyelid and orbital anatomy can cause variations in the palpebral aperture (Fig. 9.4).28

Ptosis

Ptosis is the abnormally low level of the upper eyelid.28–31 Ptosis of the upper eyelid can result from damage to the levator complex during retroseptal dissection by direct trauma, hematoma, edema, or septal adhesions.28,32–38 The normal upper eyelid level covers 2–3 mm of the superior limbus or lies at the level midway between the superior edge of a 4 mm pupil and the superior corneal limbus (Fig. 9.4). Preoperative variations in upper eyelid levels may result from the level of alertness, pharmacologic agents, direction of gaze, size of the ocular globe, orbital volume, visual acuity, and extraocular muscle balance.28 Occasionally, unrecognized ptosis manifests itself in the postoperative blepharoplasty patient. Review of the preoperative examination records and medical photography usually reveals the etiology. When no presenting condition can be documented, a surgical misadventure is implicated in the etiology.

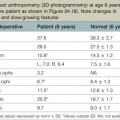

Ptosis is classified as mild at 1–2 mm, moderate at 2–3 mm, and severe at ≥4 mm.4,22,28 The amount of ptosis is documented by measuring the vertical dimensions of the palpebral apertures at the midpupillary line. The amount of levator function in millimeters is measured whenever ptosis is diagnosed in order to plan a surgical correction. The test is performed by examining the upper eyelid excursion from complete down gaze to up gaze, while blocking any contribution to upper eyelid elevation by the eyebrow (Fig. 9.7). Asymmetric or absent lid creases must be identified, because asymmetry can be accentuated with standard blepharoplasty techniques. The vertical dimensions of the palpebral apertures at the midpupillary line are also measured.23

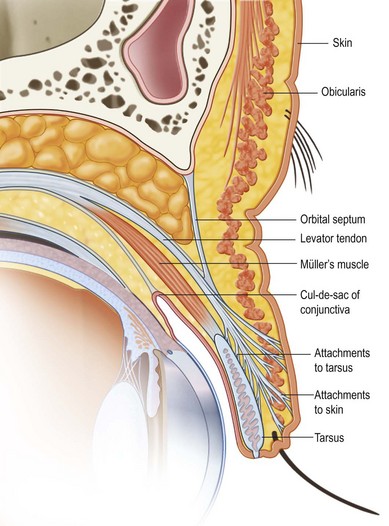

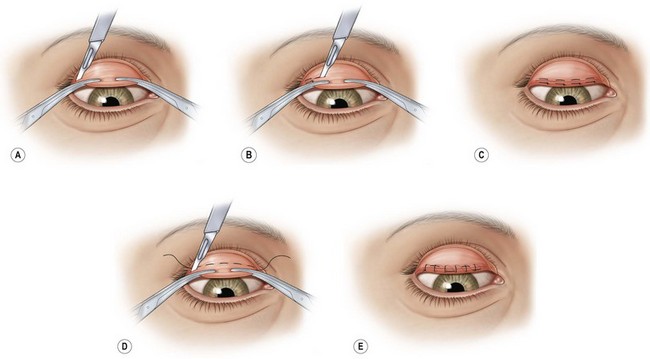

Aponeurosis disinsertion, or dehiscence, is the most common form of acquired ptosis. The typical clinical presentation is a mild (1–2 mm) to moderate (2–3 mm) case of ptosis associated with thin upper eyelids, high lid folds, and good levator excursion (Figs 9.8, 9.9).28 The levator muscle originates from the apex of the orbit and passes anteriorly, becoming aponeurotic at the superior orbital margin to insert onto the anterior two-thirds of the anterior tarsal surface. Some fibers of the aponeurosis extend to the orbicularis fascia to attach to the dermis of the upper eyelid, forming the upper lid crease. The anterior orbital fat removed during upper blepharoplasty lies posterior to the septum and anterior to the levator aponeurosis. Inadvertent penetration or detachment injury to the levator aponeurosis can occur during removal of the preseptal orbicularis oculi muscle or retroseptal fat (Fig. 9.9A).

Fig. 9.8 Levator aponeurosis dehiscence produces a high upper lid fold, thin upper eyelid, and ptosis.

(Modified from Jelks GW, Jelks EB. Blepharoplasty. In: Peck GC, ed. Complications and problems in aesthetic plastic surgery. New York: Gower Medical Publishing; 1992.)

The condition is repaired by levator exploration and advancement of the aponeurotic structures to the anterior tarsus.32–38 Patients with levator detachment should be repaired by levator advancement to the anterior tarsus. The Fasanella–Servat38 technique and its various modifications (Fig. 9.10), or variations of a tarso-mullerectomy are also excellent approaches to correct minimal ptosis.