Seborrheic Dermatitis, Dandruff

Danielle S. Applebaum

Suneel Chilukuri

I. BACKGROUND

Seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff are common, chronic, relapsing, scaling disorders which share a similar origin. Seborrheic dermatitis is thought to affect up to 5% of the general population, and its milder counterpart, dandruff, has been said to affect up to 50% of the population.1,2 When compared to patients with a normal scalp, patients with seborrheic dermatitis or dandruff have an increased number of nucleated cells/cm2 (6.8× for dandruff; 20.5× for seborrheic dermatitis) and lose a higher number of cells/cm2 after hair washing. Dandruff is a noninflammatory, mild form of seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp caused by excessive physiologic desquamation. In comparison, seborrheic dermatitis is an inflammatory, erythematous, scaling eruption in areas of the skin with a high number of sebaceous glands.

The exact cause of seborrheic dermatitis is unknown, but its etiology is believed to be multifactorial. Sebum production, the presence of and the immune response to certain Malassezia (previously Pityrosporum) yeast species (most commonly Malassezia globosa and Malassezia restricta), atmospheric humidity, and stress may all be contributing factors. Although seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff occur in areas with a high density of sebaceous glands, there is no direct correlation between sebum production and the presence or activity of disease. Furthermore, reducing the amount sebum production does not eliminate dandruff or seborrheic dermatitis. In contrast, a reduction in the number of Malassezia yeast after treatment with antifungals has been shown to improve seborrhea. Malassezia may contribute to the inflammation found in seborrheic dermatitis by the yeast’s lipase activity, the toxic metabolites they produce, and the abnormal immune response they create. Malassezia increases the number of natural killer cells and inflammatory interleukins by activating the complement pathways (classic and alternative).

Seborrheic dermatitis has a familial tendency and is found with increased incidence in a variety of medical conditions, including Parkinson disease, other neurologic disorders, HIV/AIDS, depression, other mood disorders, and tinea versicolor (Table 38-1). The incidence of seborrheic dermatitis has been reported to be as high as 30% to 83% in patients with HIV/AIDS.1,2 An increased incidence of seborrhea has also been found in patients with a personal or family history of atopic dermatitis.

II. CLINCAL PRESENTATION

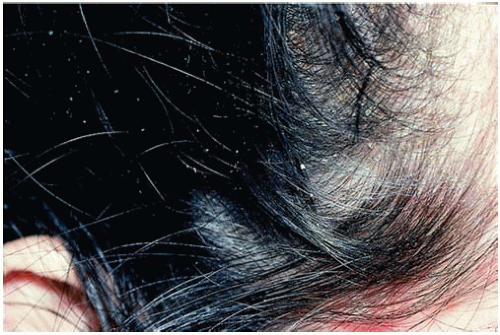

Seborrheic dermatitis typically occurs during infancy, puberty, and in adults aged greater than 50 years, with males affected more often than females. Seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff have a mild clinical course. The lesions tend to be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic (seborrheic dermatitis worse than dandruff), with episodic exacerbations associated with cold weather, stress, and infection. The lesions of dandruff appear as nonerythematous,

noninflammatory, white, or greasy scaling throughout the scalp (Fig. 38-1). The lesions of seborrheic dermatitis appear as erythematous, inflammatory, greasy, yellow to brown scaling patches or plaques affecting the scalp, face (eyebrows, eyelids, nasal alar crease, mouth, and ears), and body (central chest and genital region in adults, diaper region in infants) (Figs. 38-2 and 38-3).

noninflammatory, white, or greasy scaling throughout the scalp (Fig. 38-1). The lesions of seborrheic dermatitis appear as erythematous, inflammatory, greasy, yellow to brown scaling patches or plaques affecting the scalp, face (eyebrows, eyelids, nasal alar crease, mouth, and ears), and body (central chest and genital region in adults, diaper region in infants) (Figs. 38-2 and 38-3).

TABLE 38-1 Differential Diagnosis | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Figure 38-1. Dandruff. Note scaling with very little inflammation. (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree