Rosacea

Lauren Alberta-Wszolek

Michael C. Chen

I. BACKGROUND

Rosacea is a common and chronic inflammatory skin disease of the central face that affects at least 16 million people in the United States alone. It is characterized by two clinical components: a vascular change consisting of intermittent or persistent erythema and flushing and an acneiform eruption with papules, pustules, cysts, and sebaceous hyperplasia. Onset is most often between the ages of 30 and 50; pediatric cases have also been reported. Although women are affected three times as frequently as men, the disease may become more severe in men. Rosacea is much more common in light-skinned, fair-complexioned individuals but may also occur in darker skin types. It is estimated that 10% of individuals in Sweden have rosacea.

Etiology continues to be largely unknown. Multiple potential pathophysiologic mechanisms have been postulated, for example vascular abnormalities, dermal matrix degeneration, environmental factors, and microbial organisms, such as Demodex folliculorum and Helicobacter pylori.1 Over recent years, however, rosacea is emerging as an inflammatory disease associated with dysregulation of the innate immune system. Through toll-like receptors (TLR) as well as other receptor families, our innate immune systems respond to environmental stimuli such as UV, microbes, and physical and chemical trauma, and release cytokines as well as antimicrobial peptides in the skin as our first line of defense. Cathelicidins, in particular LL-37 found in humans, are antimicrobial peptides that are known to be both vasoactive and proinflammatory,2 exerting direct angiogenic effects on endothelium and activating innate immunity. Individuals with rosacea express abnormally elevated levels of cathelicidin3 as well as increased serine proteases,3 such as stratum corneum tryptic enzyme and kallikrein-5, compared with normal skin. These proteases lead to abnormal processing of cathelicidin, making the peptides even more proinflammatory, leading to leukocyte chemotaxis, angiogenesis, and expression of extracellular matrix components.2 Injection of these abnormal cathelicidin peptides or the enzymes that produce cathelicidin into the skin of mice leads to skin inflammation characteristic of the pathologic changes in rosacea.3 Further support of dysfunction of the innate immune system as a central cause of rosacea recently came again from Yamasaki et al.,4 revealing that, unlike other inflammatory skin disorders, the epidermis of patients with rosacea express higher levels of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR-2) compared to normal. Overexpression of TLR-2 then stimulates increased serine protease activity by keratinocytes,4 leading to higher levels of cathelicidin. While more research needs to be performed to better explain the etiology of rosacea, it appears promising that rosacea is linked to a defect in innate immunity. The facial lesions of rosacea often cause justifiable concern about personal appearance, and patients will frequently seek the care of various medical providers to help with treatment. The diagnosis of rosacea is made by fulfilling one of several primary and one of many secondary

criteria. Primary criteria for rosacea include transient erythema/flushing, persistent facial redness, papules and pustules, and increased facial telangiectasias. Secondary criteria include burning/stinging, elevated red facial plaques with or without scale, dry/scaly skin, persistent facial edema (subtypes of solid facial or soft facial type), phymatous changes, and ocular manifestations such as burning/itching, conjunctival hyperemia, lid inflammation, styes, chalazia, and corneal damage.

criteria. Primary criteria for rosacea include transient erythema/flushing, persistent facial redness, papules and pustules, and increased facial telangiectasias. Secondary criteria include burning/stinging, elevated red facial plaques with or without scale, dry/scaly skin, persistent facial edema (subtypes of solid facial or soft facial type), phymatous changes, and ocular manifestations such as burning/itching, conjunctival hyperemia, lid inflammation, styes, chalazia, and corneal damage.

II. CLINICAL PRESENTATION

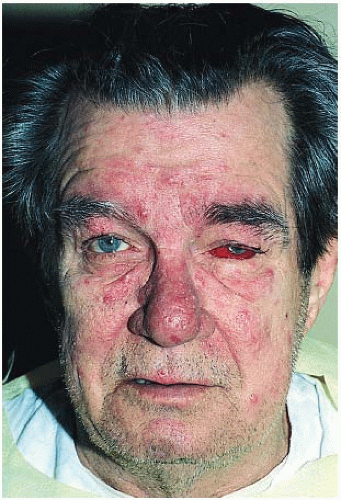

There are four subtypes of rosacea that have been defined by the National Rosacea Society Committee5 on the classification and staging of rosacea: (A) erythematotelangiectatic, (B) papulopustular, (C) phymatous, and (D) ocular.

A. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea (Fig. 37-1) is characterized by prolonged flushing and persistent central facial erythema with or without telangiectasia. Periocular skin is characteristically spared. Patients typically experience a burning or stinging sensation, which may be exacerbated by topically applied products.

B. The papulopustular type (Fig. 37-2) has persistent central facial erythema and transient acneiform papules, pustules, and cysts. Unlike acne, comedones

are not present. Inflammatory lesions may be painful. Chronic facial edema may follow repeated episodes of inflammation. In addition to the face, the lesions of rosacea may be seen on the neck, scalp, shoulders, and upper back.

are not present. Inflammatory lesions may be painful. Chronic facial edema may follow repeated episodes of inflammation. In addition to the face, the lesions of rosacea may be seen on the neck, scalp, shoulders, and upper back.

Figure 37-1. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea: Background erythema with fine telangiectasias of the central face. Note the lack of inflammatory lesions. (Image provided by Stedman’s.) |

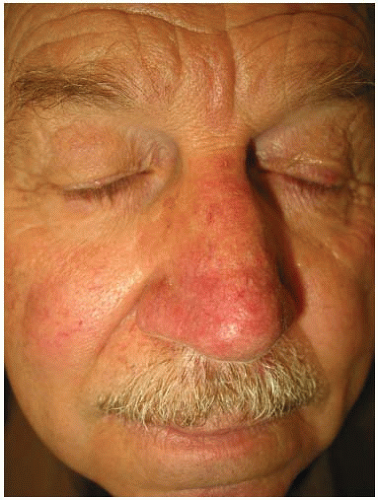

C. Phymatous rosacea (Fig. 37-3) occurs most often on the nose (rhinophyma) and is characterized by thick skin with an irregular surface, nodularities, and bulbous enlargement. Rhinophyma predominantly affects men. Careful evaluation of a nose with the changes of rhinophyma should be undertaken because basal cell carcinomas may be present, as well as less common tumors. Pseudorhinophyma can be seen when heavy eyeglasses obstruct the lymphatic and venous drainage from the nose.

D. In ocular rosacea (Fig. 37-4), blepharitis and conjunctivitis are the most common findings. Ocular complaints include stinging, photophobia, burning, tearing, scratchiness, and a sense of a foreign body being in the eye. Patients may also have a history of recurrent chalazion. Rarely, keratitis may lead to blindness. Ocular rosacea may precede the cutaneous findings by many years, but the frequency of ocular symptoms increases as rosacea progresses. The severity of the eye involvement does not correlate with the severity of facial involvement. Ocular symptoms can often be elicited on the routine investigation of rosacea patients, as more than 50% of rosacea patients will have ocular involvement.

The National Rosacea Society Expert Committee5 further classifies granulomatous rosacea as a disease variant characterized by noninflammatory, hard, brown, yellow, or red papules/nodules of the central face. It is of note that rosacea fulminans (pyoderma faciale), steroid-induced acneiform eruption, and perioral dermatitis are not considered rosacea variants but separate entities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree