Definition

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by symmetrical polyarticular arthritis, typically affecting the wrist and small joints of the hands and feet. Inflammation progresses to joint destruction with pain, deformity, and disability.

Nonarticular manifestations include rheumatoid nodules, pulmonary fibrosis, renal amyloidosis, pericarditis, endocarditis, atherosclerosis, Felty’s syndrome, keratoconjunctivis sicca, hemolytic anemia and generalized systemic symptoms such as malaise, anorexia, anemia, and weight loss. The course of RA is variable and unpredictable; premature mortality is well recognized.

The incidence of RA is generally quoted across European and North American literature as affecting 1% of the population. RA is two to four times more common in females than males, with a peak age of incidence in the seventh decade. RA may have a significant social and economic impact on the people afflicted with this disease. The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has estimated that approximately one-third of people stop work within 2 years of diagnosis and the total cost to the UK economy is £3.8 billion to £4.75 billion per year.

Diagnostic Criteria

In 2010 the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) revised the classification schema for RA ( Table 59.1 ). Diagnosis is confirmed by affecting one or more joints, not explained by another cause and a total score of 6 or greater (out of 10) in four domains: joint involvement, serology, acute phase reactants, and duration of symptoms. A key aim was to identify patients with RA early, especially those with persistent or erosive disease, in order to allow early medication.

| Patients with at Least One Joint with Clinical Synovitis, not Explained by Another Disease | Score (out of 10) |

|---|---|

| A. Joint Involvement | |

| 1 large joint | 0 |

| 2–10 large joints | 1 |

| 1–3 small joints | 2 |

| 4–10 small joints | 3 |

| >10 joints (at least one small joint) | 5 |

| B. Serology | |

| Negative RF and negative ACPA | 0 |

| Low positive RF or low positive ACPA | 2 |

| High positive RF or high positive ACPA | 3 |

| C. Acute-Phase Reactants | |

| Normal CRP and normal ESR | 0 |

| Abnormal CRP or abnormal ESR | 1 |

| D. Duration of Symptoms | |

| <6 weeks | 0 |

| ≥6 weeks | 1 |

Pathophysiology

The cause of RA is unknown and tremendously complex. Antigen presenting cells (APCs) bind and present an as yet unknown arthritogenic antigen to T-cells. The binding of co-stimulatory ligands, also on the APCs, such as CD80 and CD86, assists in activation of T-cells. T-cells, fibroblasts, and macrophages secrete numerous proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α. These recruit and activate neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, synovial cells, fibroblasts, and B-cells. Inheritance of certain HLA-II loci may mediate antigen presentation, T-cell reactivity and other immune relationships.

B-cells differentiate into plasma cells that secrete antibodies and autoantibodies. This process is abetted by IL-6. Autoantibodies include those to IgG (rheumatoid factor, RF) and citrullinated peptides (anticitrullinated protein antibody, ACPA), amongst others. The autoantibodies form immune complexes that drive the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, augmenting the inflammatory process. Activated B-cells also act as APCs. In conjunction with cells of the innate and acquired immune system there are numerous other chemokines that guide and control this intricate process.

The final stage in the pathogenesis is swollen synovium full of macrophages, T-cells, B-cells, plasma cells, and synovial fibroblasts. This synovial pannus then erodes cartilage, bone, and supporting soft tissues leading to joint destruction, deformity, and pain. Synovial proliferation around tendons (tenosynovitis) may cause tendon attrition and rupture. Joint destruction begins early and erosive changes may occur within months.

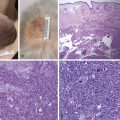

Rheumatoid nodules are typically cutaneous, demonstrating central fibrinoid necrosis surrounded by macrophages and fibroblasts and a cuff of connective tissue containing lymphocytes and plasma cells. Rheumatoid nodules typically occur at sites of repeated mechanical stress or over bony prominences such as the olecranon, the calcaneum, and the metacarpophalangeal joints; they are associated with more aggressive disease. Due to generalized dysfunction of the immune system RA patients have an increased susceptibility to infection.

Management Principles and Operative Options

Assessment and Evaluation

Referral to a rheumatologist should be made for any patient with persistent and unexplained synovitis. This includes patients with normal inflammatory markers and those who are RF-negative. Referral should be expedited if the synovitis affects multiple joints, or if the duration of symptoms has been longer than 3 months. There is an urgency to diagnose RA since prompt treatment has been shown to reduce permanent joint damage.

RA should be managed by a multidisciplinary team (MDT), which may include a rheumatologist, occupational therapist, hand surgeon, besides other allied health professionals.

General Assessment

Assessment includes examination for joint synovitis and extraarticular manifestations ( Box 59.1 ). Blood tests should include inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). Serology should include RF and ACPA, the latter being more specific for RA. Baseline full blood count (FBC), liver, and renal biochemistry are useful for planning treatment.

Clinical evaluation

Joint synovitis and extraarticular manifestations

Blood work

ESR, CRP, RF, ACPA, complete blood count, liver and renal biochemistry

X-rays of hands and feet

Radiological Features

X-rays provide a record of the permanent damage of RA ( Fig. 59.1 and Box 59.2 ). Changes include: surface erosions, cystic changes, cortical thinning, osteoporosis, and progressive joint narrowing through to frank ankylosis, subluxation, and dislocation. In mutilans arthropathy there is bony destruction, which may progress rapidly.

Joint narrowing and destruction progressing to ankylosis

Erosions

Cortical thinning

Osteoporosis

Subluxation/dislocation

Bony destruction (mutilans)

The Sharp and Larsen scores are the most widely used radiological assessments for RA. Each scores X-rays of the hands, wrists, and feet; higher scores indicate greater bony destruction. The Sharp method scores bony erosions and joint space narrowing separately over 31 areas to give a score from 0 to 448. The Larsen score assesses 20 joints to give a score out of 100. Although the Larsen score is more widely used, the Sharp assessment is more sensitive for detecting changes over time. The Sharp and Larsen assessments have significant correlation with each other and with the extent of joint and cartilage destruction.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is increasingly used to detect pre-erosive synovitis, and early bone damage not seen on standard radiography. Fat-suppressed gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images will demonstrate pre-erosive synovitis, tenosynovitis, and bony erosions. The presence of bone marrow edema, seen on T2-weighted images, is also predictive of the development of bony erosions. Identification and treatment of subclinical synovitis and prevention of bony erosions are the aims of more aggressive medical management regimes.

Identifying Patients with Aggressive Disease

One of the key goals of initial assessment is to identify those patients with signs that suggest an aggressive disease process ( Box 59.3 ). Such patients are monitored closely; a poor response to first-line medical treatment may warrant early use of biologic therapies to gain early control of the disease.

Positive RF or ACPA

Early functional limitations

Multiple swollen or tender joints

Early bony erosions on X-ray

Extra-articular manifestations

High ESR or CRP

Assessment of Disease Activity

People with newly-diagnosed RA require regular assessment of disease activity until the disease is stable. Usually this consists of monthly to trimonthly review, including CRP and a Disease Activity Score (DAS28). The DAS28 is a measure of disease activity in RA; an online tool collates a clinical assessment of 28 specified joints, serum inflammatory markers, and a visual analog scale (0–10) of the patient’s global function. A score greater than 5.1 indicates active disease and less than 3.2 indicates well-controlled disease. A score of less of than 2.6 indicates remission. Alteration in the DAS28 can be used to assess response to treatment. Until the disease is well controlled repeat radiography of the extremities is recommended every 6–12 months. Persistent erosive disease despite good symptom control may warrant a change in medication regime. Stable disease only requires annual review.

Assessment of Disability Status and Health Status

RA is a chronic illness and it is crucial to document both the disability and health status of each patient.

The most common measure of disability status is the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ – DI), which has eight categories covering dressing, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip, and activities. For each domain, a score of 0–1 represents mild to moderate disability, 1–2 moderate to severe disability, and 2–3 severe to very severe disability.

Health status is frequently assessed via the Short Form 36 (SF-36). The SF-36 has eight domains covering vitality, physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, ability to perform social roles, ability to perform physical roles, ability to perform emotional roles, and mental health. Each of the eight sections are scored from 0 to 100, with 100 being normal health status.

Surgical Options

The benefits of surgery include relief of pain, recovery of function, and cosmetic improvement. Rheumatoid deformities are frequently multifactorial and they must be assessed within the context of the patient’s rheumatoid pathology and global function. The decision to offer surgery requires evaluation of the surgical problem and functional limitations. There are general principles when creating a rheumatoid management plan: operate on the lower limb before the upper limb, operate proximally then distally, offer reliable procedures with the highest chance of success first. Souter presented his personal reflections on the relative merits of different rheumatoid hand procedures and felt that the three most efficacious procedures were extensor synovectomy combined with excision of the ulna head, wrist stabilization, and thumb metacarpophalangeal joint fusion. Critical analysis of different surgical procedures is, however, not evidenced in the literature and randomized controlled trials comparing different surgical treatments are rare. There is also considerable discrepancy between the views of surgeons and rheumatologists, hence the benefits of managing rheumatoid patients within the confines of a MDT.

Synovectomy and Tenosynovectomy

Synovectomy is the excision of inflamed synovial tissue within a joint and tenosynovectomy implies excision of inflamed synovial tissue affecting tendons. The benefits and roles of synovectomy and tenosynovectomy are quite different; refractory tenosynovitis benefits more clearly from surgical treatment.

Synovitis is typically managed with systemic medications, although isolated persistent synovitis may benefit from intraarticular steroid injection. Recalcitrant synovitis or incidental synovitis, discovered during the course of a surgical procedure may be excised but there is no evidence that synovectomy alters disease course or reduces intraarticular cartilage destruction. Synovectomy may relieve pain and may be complicated by stiffness.

Tenosynovitis may affect any tendon surrounded by synovium. Extensor tenosynovitis typically causes dorsal wrist swelling, extending beneath and restrained by the extensor retinaculum. The synovial pannus may cause tendon attrition and rupture. Extensor tenosynovectomy is recommended to prevent tendon rupture when synovitis persists for more than 3–6 months despite aggressive medical management. A dorsal longitudinal incision allows exposure of all extensor compartments ( Fig. 59.2 ). The extensor retinaculum is elevated from the sixth to second compartments; the tendons are examined for rupture and tenosynovectomy performed. The distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) should be examined and treated (synovectomy/capsular repair/Darrach procedure) if required. The retinaculum may then be split in half transversely, with one half being placed beneath the tendons to provide protection from the DRUJ and the other used to reconstitute the extensor retinaculum and prevent bowstringing. Brumfield et al reviewed 78 rheumatoid patients, with 102 dorsal wrist tenosynovectomies, intraarticular synovectomies, and a Darrach (ulnar head) resection. With an average follow-up of 11 years, pain was improved in 83% of wrists, with a 13-degree loss in wrist movement. Synovitis recurred in 16% of patients, subsequent tendon ruptures occurred in 5% of patients but radiologically the disease progressed unchecked. Twenty-seven wrists required revision surgery, including tendon transfers, partial and total wrist fusion, and wrist arthroplasty.

There are three principal types of flexor tenosynovitis: isolated carpal tenosynovitis, palmodigital tenosynovitis, and diffuse tenosynovitis. Synovial proliferation within the carpal tunnel may cause carpal tunnel syndrome. Wrist tenosynovectomy is performed through an extended carpal tunnel incision preserving the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. Bony protrusions on the floor of the carpal tunnel should be smoothed. Palmodigital tenosynovitis typically causes diffuse swelling, triggering, and restriction of flexion, and may progress to rupture of flexor tendons. Again, if there is no improvement after 3 months of intensive medical treatment then tenosynovectomy is indicated. Palmar synovectomy requires broad exposure and may necessitate extension into the digits. Digital triggering may be improved by synovectomy, nodule excision, and A1 pulley release. Adrian Flatt recommended release of the radial side of the A1 pulleys and cautioned against the release of multiple A1 pulleys, which may potentiate ulnar drift. In this situation resection of the one slip of flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) is a reasonable alternative.

Wrist

The wrist is the major load-bearing joint of the hand, therefore pain or instability may significantly impair function. Wrist involvement affects up to 50% of patients within 2 years of disease onset, increasing to 90% after 10 years ; wrist surgery is both common and beneficial to rheumatoid patients.

Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Wrist Disease

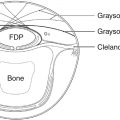

The wrist is inherently unstable and relies on an extensive collection of extrinsic and intrinsic ligaments to preserve stability between the forearm bones and carpus. Extrinsic ligaments extend from the radius and ulna to the carpus; palmar ligaments are stronger than dorsal ligaments. Intrinsic ligaments link the carpal bones only. The scapholunate and lunotriquetral ligaments secure the proximal carpal row and are key in maintaining the mechanics of force transmission through the wrist. Further stability is provided by the flexor and extensor retinaculi, and the 23 extrinsic extensor and flexor tendons that surround the wrist. The triangular fibrocartilage complex provides stability to the DRUJ. Normally, 80% of load is transmitted through the capitate, scaphoid, and lunate to the radius. Pathological weakening of ligaments distorts the biomechanics of the wrist, initially during loading and later at rest. Weakening of the important volar radiocarpal ligaments (radioscaphocapitate and radiolunotriquetral) contributes to ulnar translation and volar subluxation of the carpus. The ulna remains in its original position and becomes relatively prominent as the carpus subluxes. This collection of signs is termed a caput ulnae deformity ( Box 59.4 ). Bony destruction and intrinsic ligament failure, especially scapholunate ligament disintegration, leads to carpal dissociation and loss of carpal height. With ulnar translation of the carpus the metacarpals fall into radial deviation.

Ulnar translation and radial deviation of the carpus

Palmar subluxation of carpus

Supination of carpus

Prominent ulnar head

X-ray Assessment of the Rheumatoid Wrist

Standard posteroanterior (PA) and lateral wrist X-rays should be assessed for features of RA and caput ulnae deformity. Two further aspects should be assessed: carpal height ratio and ulnar translation. The key features to document are listed in Box 59.5 .

General features of rheumatoid arthritis: osteoporosis, erosion, diminished joint space

Focal area of arthritis: radiocarpal joint, midcarpal joint

Features of caput ulnae deformity

Carpal height

Ulnar translation

Status of the DRUJ/ulnar head

The carpal height ratio as described by McMurtry et al in 1978 is the distance from the third carpometacarpal joint (CMCJ) to the lunate fossa divided by the length of the third metacarpal. The average carpal height ratio is 0.53 (range 0.45–0.60). Other methods of calculation are also available.

A rapid semiquantitative measure of ulnar carpal translation can be made by assessing the position of the lunate relative to the radius; approximately 50% of the lunate should reside over the radius. A formal measure, described by Chamay and Della Santa, can be made by calculating the distance from the center of the capitate head to the long axis of the ulna, divided by the length of the third metacarpal; the average is 0.3 (range 0.27–0.33).

Classifications of Rheumatoid Wrist Disease

There have been several classification systems for RA of the wrist. The Larsen classification is a radiographic descriptive classification ( Table 59.2 ).

| 0 | No changes |

| 1 | Soft tissue swelling, demineralization |

| 2 | Marginal erosions, radial deviation |

| 3 | Articular erosions, joint space narrowing, mild radiocarpal instability |

| 4a | Midcarpal ankylosis, major radiocarpal instability |

| 4b | Radiocarpal ankylosis, stable |

| 5a | Destruction of carpus, radiocarpal dislocation |

| 5b | Destruction of carpus, complete ankylosis |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree