22 Reconstruction of the nipple-areola complex

Synopsis

Creation of the nipple-areola complex allows the reconstructed breast mound to truly resemble the natural breast.

Creation of the nipple-areola complex allows the reconstructed breast mound to truly resemble the natural breast.

The overall plan for the resection and reconstruction is a collaborative effort between the medical oncologist, general surgeon, and plastic surgeon.

The overall plan for the resection and reconstruction is a collaborative effort between the medical oncologist, general surgeon, and plastic surgeon.

Many of the currently used flaps are derivatives of the basic design of the skate flap and star flap.

Many of the currently used flaps are derivatives of the basic design of the skate flap and star flap.

The most common complications with local flap techniques are projection loss, flap/nipple necrosis, dehiscence, malposition, and infection. When other graft types are used, complications related to graft loss, extrusion, and exposure are possible.

The most common complications with local flap techniques are projection loss, flap/nipple necrosis, dehiscence, malposition, and infection. When other graft types are used, complications related to graft loss, extrusion, and exposure are possible.

History

Creation of the nipple represents the last stage of breast cancer reconstruction. Many of the techniques and flap types have been developed and are used as an attempt to either exactly match the contralateral nipple or create two nipples that achieve a round, projected appearance. Generally, the long-term appearance of the reconstructed nipple contributes significantly to the patient’s overall satisfaction with their breast reconstruction.1

The evolution of NAC creation began with Adams initial description of the nipple-areola graft and labial graft in the 1940s.2,3 Following this, Millard proposed the nipple-sharing concept, where the contralateral nipple tissue was used as a composite graft for the reconstructed nipple.4 This eliminated distant donor sites and provided and exact match in tissue type. Next, various other grafts from toe pulp, auricular cartilage, and mucous membranes were also attempted and proven somewhat successful in providing tissue with projection, but at the expense of a significant donor site morbidity.5–7 A paradigm shift occurred in NAC reconstruction with the descriptions of the quadropod flap, dermal fat flap, and T-flaps in the 1980s.8–10 These flaps, based on smaller local flaps, allowed for rearrangement into a nipple configuration. In the 1980s and 1990s, multiple different local flaps were being described using the concepts of local flap rearrangement with and without skin grafts including the skate flap,11 star flap,12 CV flap, Bell flap,13 and the S-flap.14 Lastly, the increasing use of synthetic materials and allografts in reconstructive surgery has allowed for new, innovative methods for projection augmentation and revisional NAC reconstruction.

Diagnosis and patient presentation

Most patients will have the nipple and areola resected during skin-sparing mastectomies and included in the specimen as the nipple contains ductal breast tissue. Only a select few patients will be eligible for a nipple-sparing mastectomy, which is usually determined by the size and proximity of the cancer to the nipple.15 Although preservation of the nipple leads to improved patient satisfaction,16 most patients are not candidates for keeping the native nipple. The overall plan for the resection and reconstruction is a collaborative effort between the medical oncologist, general surgeon, and plastic surgeon. Most times, patients will have the entire nipple-areolar complex (NAC) removed. Regardless of the disease process, recreation of the NAC represents a challenging issue with multiple possible reconstructive options.

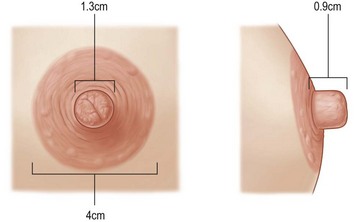

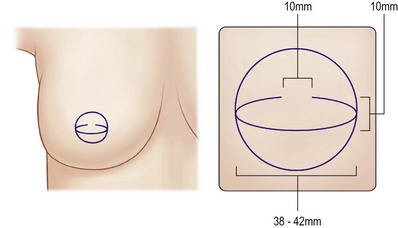

In bilateral reconstruction, the surgeon must make use of standard values to create a nipple position, size, and areola size. A review of 600 breasts showed that the mean diameter of the areola is approximately 4 cm, with average nipple diameter being 1.3 cm and the average nipple projection being 0.9 cm (Fig. 22.1).17 The average nipple-areola and areola-breast proportion is approximately 1.3.18 These numbers can be useful guiding principles, in particular, in bilateral cases where symmetry and ideal NAC creation is desired.

Timing of NAC reconstruction is crucial to the final aesthetic result. Surgical decisions made too early may result in asymmetric placement of the nipple. Key factors in the decision-making mainly focus on adjuvant breast cancer therapies and revisional reconstructive procedures. Adjuvant therapies need to be taken into consideration as the tissue healing effects of radiation and chemotherapy may compromise final outcomes. Also, revisional procedures can change breast dimensions and may lead to asymmetry of a previously symmetrically reconstructed nipple. Taking these points into consideration, the ideal timing for reconstruction is approximately 3–5 months after the last revisional reconstructive surgery. This allows for swelling and inflammation to subside, while allowing for settling of the reconstructed breast mound into its final position.19

Patient selection

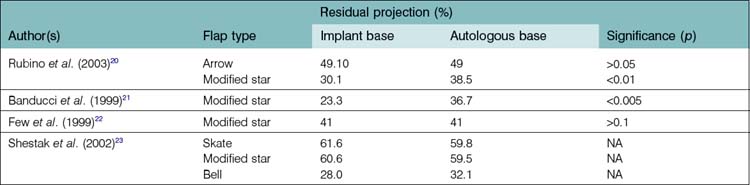

The type of previous breast reconstruction is another important factor to consider in patient selection. Patients who undergo prosthetic-based breast reconstruction will have a thin, expanded skin-subcutaneous tissue base, usually with a centrally placed mastectomy scar. On the other hand, in autologous reconstruction, patients will typically have a variable sized donor tissue skin paddle with an elliptical or circular shaped scar with a thick base. As discussed later, these factors are important in eventual NAC reconstruction as thin flaps can potentially decrease nipple projection and poorly located scars can prohibit the use of certain flap techniques due to interference with blood supply (Table 22.1).

Surgical techniques

Composite nipple graft

Many of the initial methods for nipple reconstruction were by way of various types of skin and composite grafts. The initial descriptions of using grafts involved ipsilateral nipple-areola grafts.2 Eventually, the concept of contralateral nipple grafting and distant site composite grafting were attempted and proven successful.3,4,24,25 Labial tissue and toe pulp were initially used and advocated, but donor site morbidity has led to reluctant use of these grafts.3,6,24 Nipple-banking was also used, but uncertainty of the oncologic safety of this method has led surgeons to abandon this technique. Nipple-sharing technique continues to be a popular method for nipple reconstruction with the presence of a prominent contralateral nipple.

Initiated by Adams in 19442 and described by Millard in 1972,4 contralateral nipple grafts have remained as a popular method for nipple reconstruction in patients with excess contralateral nipple projection. Patients with projection in excess of 5–6 mm are ideal candidates for composite nipple grafts. Many patients have reservations about this method of nipple reconstruction due to: (1) fear of contralateral surgery; (2) donor site morbidity, and (3) decreased contralateral nipple sensation.

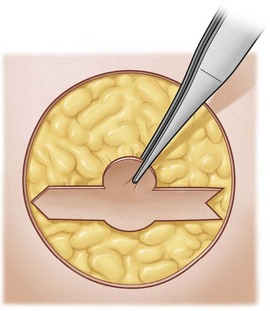

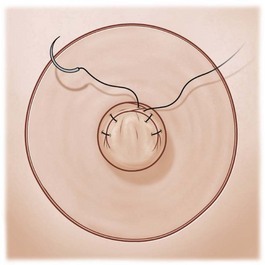

When excess projection is present, the technique for composite nipple grafting is straightforward. The basic technique first entails de-epithelialization of the future nipple site of reconstructed breast (Fig. 22.2). Then, a scalpel is used to transversely remove the distal 40–50% of the contralateral nipple (Fig. 22.3). The harvested nipple is then placed in the proposed site and sutured into place (Fig. 22.4). The donor nipple is then closed with either a purse-string suture or interrupted sutures. Close attention is paid to avoid fluid accumulation beneath the grafted site. Skin grafting of the areola can be performed at this time if excess tissue is available or from donor sites such as the inner thigh.26,27 After the procedure, a bolster dressing or gel-filled silicone nipple protector is used to avoid shearing.

As previously mentioned, one of the feared aspects of composite nipple grafts is the donor site morbidity. One study showed that patients subjectively felt that the donor nipple had the same sensation as prior to surgery and that erectile function was similar. Statistically, the study found that punctate touch stimulus to monofilament was normal 6 months postoperatively.28

Zenn et al. reviewed 57 patients who underwent composite nipple grafting. They found that only 47% of patients considered donor site sensation as “normal,” but found that 96% of patients were happy with the overall appearance, with 87% retaining erectile function in the donor nipple. In contrast, in the grafted nipple, the study found that 35% of patients had sensation in the reconstructed nipple within an average of 6 months. Interestingly, 42% of patients reported to having erectile function in the reconstructed nipple within an average of 3 months. In addition, they found complete graft take in both patients that had previous irradiation.29

Hints and tips

• Excellent option for patients with contralateral nipple >1 cm projection

• Countertraction suture and No. 11 blade help to harvest nipple accurately

• Early postoperative discoloration is normal and expected

• Irrigate blood and clot beneath the nipple with an 18-gauge catheter after securing to prevent fluid accumulation.

Traditional flaps

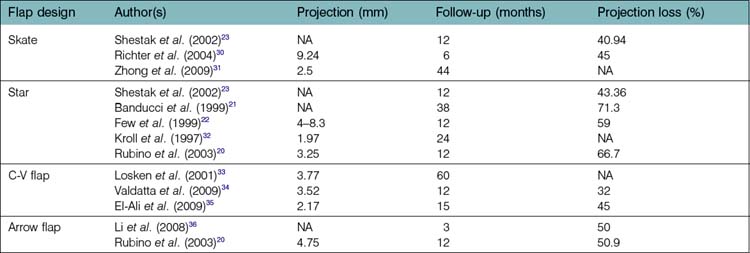

Many of the currently used flaps are derivatives of the basic design of the skate flap and star flap. This section describes the basic concepts, designs, and uses of these two flaps and many of the newer modifications and derived flap designs (Table 22.2).

Skate flap

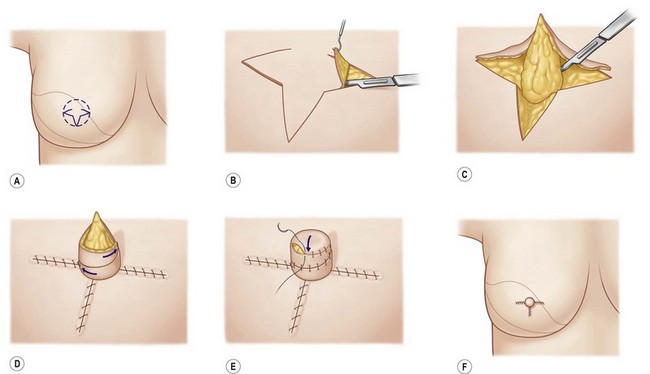

Since Little’s initial description on how to design the skate flap in the 1987,11 there has been many attempts at modifying the technique. The original design of the skate flap as described by Little, is shown in Figure 22.5. This flap has reliably produced long-term projection and is used when a projected appearance is required. Traditionally, this type of flap is used in conjunction with a skin graft for immediate areola reconstruction. The design is based on a central axis. After the appropriate site is selected, the diameter of the areola is determined; either from the opposite side or averaging 4 cm. A line bisecting the intended areola is marked and used to determine the base of the flap. The base should be directed away from the mastectomy scar in order to maximize blood flow. The line is then split into thirds. The inner and outer thirds will be used as the wings that fold to form the sidewalls of the nipple. After this line is established, a semicircular line is drawn from the two edges of the bisected line. The midpoint of this arc will represent the most projected portion of the future nipple. Varying this distance will add/lessen projection to the nipple and thoughtful placement of this arc is recommended.

The traditional design of the skate flap de-epithelializes the remainder of the areola. A doughnut shaped skin graft is then prepared and secured on the donor site and de-epithelialized area. This approach allows for a texture and color difference to the areola more closely resembling a native areola.11

Modifications to the skate flap have been developed to improve long-term outcomes and decrease donor site morbidities. Many of these techniques attempt to limit distant skin graft harvests. Bogue et al. describes a modification that closes the skate flap donor site primarily (Fig. 22.6). His modification, similar to Nahabedian’s elongated C-flap (Figs 22.7),19 decrease the tension required to close the donor site left from a traditional skate flap. They evaluated 31 nipple-areolar reconstructions using a skate flap design with tapered distal ends in order to facilitate primary closure. After elevation and nipple creation, the donor site is primarily closed. Then, a round template is used to outline an areola. The areola is then elevated as a full-thickness graft up to the base of the flap and then laid back down and a bolster dressing applied. Although all patients had satisfactory results, immediate and long-term projection is compromised by the tapered flap design.37

Richter et al. found that the skate flap was the best local flap to give projection. They followed 29 patients who had skate flap nipple reconstruction for an average of 10.9 months. Although they found an average decrease in projection of 45%, the skate flap group produced a mean nipple projection of 9.24 mm at least 6 months after reconstruction.30

Shestak et al. found that the skate flap gave a predictable long term projection after 12 months. They followed a subset of 23 patients who underwent skate flap nipple reconstruction at 3-month intervals in order to assess projection loss. They found that the skate flap was an appropriate choice when the projection goal is >5 mm. The greatest amount of projection loss occurred within the 6 months of surgery and seemed to stabilize after that time period. After 12 months, they found an average projection loss of 40%.23

Hints and tips

• Including more subdermal fat in central base gives more reliable projection

• Longer flaps increase tension if primary closure desired leading to flattening of breast

• Skin graft from scar revision areas can be used to minimize donor sites

• Will give the most projected appearance of flap techniques.

Star flap

The star flap was first described by Anton et al. using a three-wing flap to create moderate projection.12 The star flap utilizes similar principles in flap design as the skate flap. As originally described, this flap has the advantage of eliminating skin graft donor site morbidity by allowing for primary closure and possibly an improved cosmetic result. On the other hand, the main disadvantages of the star flap are the lack of projection when compared with the skate flap, and loss of long-term projection.38 Kroll et al. followed 47 patients who underwent star flap nipple reconstruction. He found that mean projection achieved was 1.97 mm after a 2-year follow-up.32 Few et al. used a modified star-dermal fat flap technique on 93 nipple reconstructions. They designed a flap with a blunted central wing and two opposing lateral triangles, or wings. The flap lengths directly correlated to the gain in projection. They found that 1 cm in flap length gave 0.16 cm in projection. In addition, long-term projection loss was 59% using their modification.22

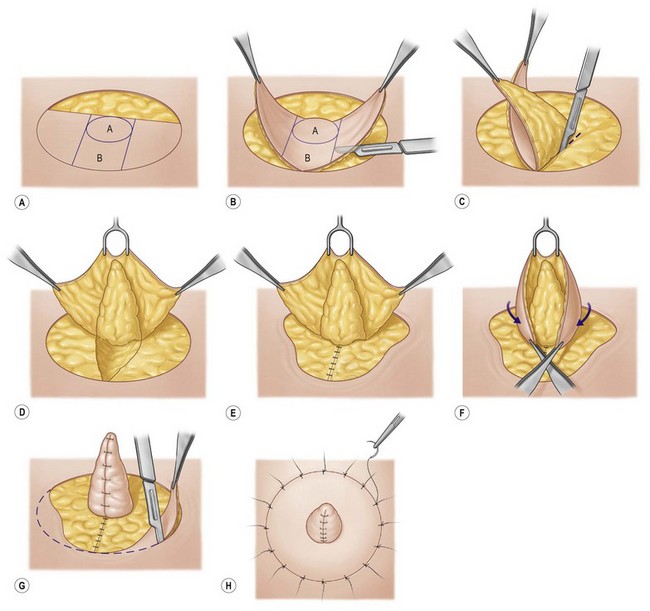

The basic design of the star flap is based on a three-wing pattern (Fig. 22.8). Similar to the skate flap, the central wing base width determines the width of the nipple. The outer star wing lengths vary depending on the size of the contralateral NAC. After drawing the appropriate pattern, dissection begins on the outer wings. In contrast to skate flap elevation, the outer wings are elevated in the subdermal fat plane paying close attention to include subcutaneous fat. The central wing is then elevated from distal to proximal while including an increasing amount of subcutaneous fat. After flap elevation, one of the outer wings are rotated along the nipple base and sutured into position. The second outer wing is then rotated around the nipple and the distal end is sutured anterior to the base of the first outer wing. After secured in place, central wing is brought over the top to form the distal tip of the nipple and secured in place.

Shestak et al. used the star flap in patients with <5 mm of contralateral nipple projection and no areola projection. He followed 28 patients for 12 months and analyzed the degree of loss of projection. Similar to the skate flap, he found that the greatest loss of projection occurred in the first 3 months and stabilized at 6 months. They found an average of 43% loss of projection at 12 months postoperatively.23

C–V flap

The basic design of the flap is represented in Figure 22.9A. Flap elevation begins at the outer V-segments and proceeds toward the central, C-segment. Dissection will typically include a thin subdermal fat layer. After elevation, the donor site is closed directly. The central segment will then be elevated with a deeper layer of subdermal fat in order to provide bulk to the nipple. After the flap has been elevated, the donor site is approximated and the two outer V-flaps are rotated into place similar to that of the skate flap (Fig. 22.9B). The two flaps are rotated along the base of the nipple and sutured together to provide the support for projection opposite the base. The central flap is then used to round the tip of the nipple and sutured into place (Fig. 22.9C).

Valdatta et al. found good overall satisfaction when using the C–V flap in 29 patients. He also found that average nipple projection was 3.52 mm compared with 4.96 mm on the native nipple at 1 year postoperatively. Projection loss after 1 year was 32%, but found an increase in diameter of the reconstructed nipple of 17%. In fact, the volume calculated of the reconstructed nipple was maintained after 1 year.34

Losken et al. found maintained projection using the C–V flap after 5-year follow-up. In comparison with the native nipple, projection was not statistically different with the reconstructed nipple measuring 3.87 mm compared with 4.71 mm on the native side. Overall patient satisfaction was 81%, with satisfaction with nipple projection being only 42% after the 5-year follow-up.33

Modifications to the C-V flap have been developed in attempts to improve long-term outcomes and stability.35,39,40 In attempts to add volume to the nipple, Mori and Hata39 and Brackley and Iqbal,40 report de-epithelialization of the lateral V-segments, providing increased bulk and possibly increasing long-term projection. Importantly, in nipple reconstruction to expander/implant patients, providing increased vascular tissue to the nipple core can compensate for dermal thinning commonly seen in implant-based reconstruction.

Arrow flap

Originally described and designed by Thomas in 1996 as a method for geometrically analyzing nipple proportions, the nipple design later used to construct the arrow flap was introduced.41 Rubino et al. introduced his “arrow flap” modification to prevent nipple flattening and retraction.20 The basic design is similar to the C–V flap design except the outer wings are designed to resemble the two sides of an arrow. Rubino added a modification to include an area of de-epithelialization to the flap design, which adds bulk to the nipple construct (Fig. 22.10). Dissection of this flap employs the same techniques used for the previous flaps described. As shown in the figure, the two arrow ends are designed to oppose one another along the base of the flap and the closure resembles a Z-plasty in that the vertical scar becomes re-oriented (Fig. 22.11).

Fig. 22.11 The outer segments are rotated to form the base of the nipple and the two sides of the “arrow shape” (see Fig. 22.10) as closed in a V-configuration.

Rubino et al. compared the long-term results of using the arrow flap compared with the modified star flap. Each group contained 16 nipple reconstructions and he found that the arrow flap maintained 49.1% projection after 12 months, with an average projection of 4.75 mm.20