Reconstruction of defects of the lips after Mohs micrographic surgery should encompass functional and aesthetic concerns. The lower lip and chin compose two-thirds of the lower portion of the face. The focus of this article is local tissue transfer for primarily cutaneous defects after Mohs surgery. Various flaps exist for repair. For small defects, elliptical excision with primary closure is a viable option. During reconstruction of the lip, all of the involved layers need to be addressed, including mucosa, muscle, and the vermillion or cutaneous lip. It is especially important to realign the vermillion border precisely for optimal results.

Key points

- •

The cutaneous and mucosal lips are critical structures of the face performing a vital role in oral function and competence as well as overall facial aesthetics.

- •

Attention to the aesthetic boundaries of the lip, cheek, and nasal subunits will result in the best reconstructive outcomes of the perioral region.

- •

Revision surgery, including Z-plasty, is often necessary to achieve the best long-term results.

Introduction

The lips are prominent facial features important for both functional and aesthetic aspects of daily life. Defects from Mohs micrographic surgery can alter the normal lip appearance and impact patients’ self-image and their quality of life. Successful repairs encompass both functional and aesthetic concerns. The goals of reconstruction are the restoration of oral competence, maintenance of oral opening, restoration of normal anatomy, and provision of an acceptable aesthetic outcome.

Defects of the lip are challenging to reconstruct for several reasons. There is an increase in the risk of anatomic distortion through increased wound contraction due to the lack of a substantial fibrous framework. The area is under constant motion, and wound contracture can lead to poor functional and aesthetic outcomes. As the lips are within the observational center of the face, even minor lip defects require meticulous reconstruction to minimize the distraction caused by the defect. A review by Coppit and colleagues in 2004 found no major advances in lip reconstruction but, rather, continued advances in already accepted techniques. When reconstructing the cutaneous lip, it is preferable to confine tissue movement within the aesthetic region of the lips, unless this causes distortion of adjacent structures, such as the melolabial crease. Local flaps generally provide the best match for the quality of the skin and mucosa of the lips. The focus of this article is on local tissue transfer for primarily cutaneous defects after Mohs surgery.

Introduction

The lips are prominent facial features important for both functional and aesthetic aspects of daily life. Defects from Mohs micrographic surgery can alter the normal lip appearance and impact patients’ self-image and their quality of life. Successful repairs encompass both functional and aesthetic concerns. The goals of reconstruction are the restoration of oral competence, maintenance of oral opening, restoration of normal anatomy, and provision of an acceptable aesthetic outcome.

Defects of the lip are challenging to reconstruct for several reasons. There is an increase in the risk of anatomic distortion through increased wound contraction due to the lack of a substantial fibrous framework. The area is under constant motion, and wound contracture can lead to poor functional and aesthetic outcomes. As the lips are within the observational center of the face, even minor lip defects require meticulous reconstruction to minimize the distraction caused by the defect. A review by Coppit and colleagues in 2004 found no major advances in lip reconstruction but, rather, continued advances in already accepted techniques. When reconstructing the cutaneous lip, it is preferable to confine tissue movement within the aesthetic region of the lips, unless this causes distortion of adjacent structures, such as the melolabial crease. Local flaps generally provide the best match for the quality of the skin and mucosa of the lips. The focus of this article is on local tissue transfer for primarily cutaneous defects after Mohs surgery.

Anatomic considerations

The lips are a major component of the lower third of the face. The lip encompasses the area from the subnasale to the mental crease and from commissure to commissure ( Fig. 1 ). The lips are divided into the cutaneous, vermilion, and mucosal parts. Vermilion is specialized mucosa that covers the lips. Vermilion is divided into the dry (external) and wet (internal) vermilion. The white lip, or cutaneous lip, is made up of the nonvermilion skin surrounding the lip. The cutaneous lip extends from the nasal base superiorly, to the labiomental crease inferiorly, and the nasolabial folds laterally. The lower lip acts as a dynamic dam to retain saliva and prevent drooling. The lips are defined by the red-white vermilion-cutaneous border. The white roll separates the skin and vermilion, whereas the red line separates the dry vermilion from the wet vermilion or intraoral labial mucosa. Cupid’s bow is composed of the apices of the upper lip and central depression and is of variable prominence. The medial upper lip vermillion prominence is the tubercle. The philtral columns extend up to the columella, separated by the philtral groove. The upper lip consists of a medial and 2 lateral subunits, demarcated by the philtral ridges and the nasolabial folds ( Fig. 2 ).

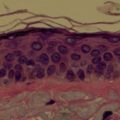

Each lip is composed of the orbicularis oris muscle that is invested by skin and subcutaneous tissue externally, by mucosa and submucosa intraorally, and the vermilion over its free edge. The lips contain a circular muscular structure, the orbicularis oris, that is pulled into an oval by radially oriented cheek suspensory muscles ( Fig. 3 ). All of these muscles are innervated by the facial nerve. The second division of the trigeminal nerve via the infraorbital nerve provides sensory innervation to the upper lip, and the third division of the trigeminal nerve via the inferior alveolar nerve provides sensory innervation to the lower lip and chin. The arterial supply of the lips is the labial artery, which is a branch of the facial artery. Veins follow the arteries.

Functional considerations for repair include maintenance of oral competence for facilitation of oral intake, containing secretions, articulation, kissing, smiling, and expressing emotion. The lips are essential for phonation of the letters M, B, and P. Aesthetic considerations include symmetry, normal anatomic proportions, presence of a philtrum, normal oral commissures, and the presence of a vermilion-cutaneous white border. Other considerations are the age, general state of health of patients, previous treatment, tissue laxity, and dental status.

Primary repair

The preferred method for reconstruction of most cutaneous tumors of the lip is fusiform excision and primary wound repair. Small defects of the cutaneous lip can be closed with elliptical excision with primary closure. The fusiform excision should be oriented with its long axis parallel to the relaxed skin tension lines if possible ( Fig. 4 ). M-plasty can aid in closure that does not cross aesthetic borders of the lips or into the vermilion.

Mucosal Lip

Labial mucosal advancement flap

Defects involving the vermilion only can be reconstructed with a labial mucosal advancement flap ( Fig. 5 ). Mucosal incisions are made toward the gingivobuccal sulcus, and mucosa is elevated off of the orbicularis oris muscle. The flap has a 2:1 length-to-width ratio, and a back cut is included if needed to allow for advancement of the flap into the defect. A pedicled orbicularis oris flap can be rotated into the base of the defect if muscle was removed with tumor and the mucosal flap does not provide sufficient bulk. A free buccal mucosal flap can be used for coverage of nonvisible portions of the mucosal defect and for coverage of the mucosal donor site.

Central Cutaneous Lip

Advancement flap

Cutaneous lip advancement flaps are most commonly used to reconstruct central cutaneous lip defects. Dissection is in the subcutaneous plane superficial to the orbicularis oris and facial muscles. As the flap is advanced medially, its base often overlaps the oral commissure; this redundancy of skin may require excision. With medial advancement of the flap, the oral commissure may be pulled superiorly or inferiorly. The displacement of the oral commissure may be self-correcting as the natural pulling of the lip musculature causes a corrective adjustment over time ( Fig. 6 ).

H-plasty (bilateral unipedicled advancement flaps)

An H-plasty is another option if primary closure or advancement does not provide suitable tissue volume for closure ( Fig. 7 ). For the upper lip, incisions for opposing advancement flaps are made along the vermilion-cutaneous border and immediately below the nasal sill ( Fig. 8 ). For the lower lip, incisions are placed in the vermilion-cutaneous border and the mental crease. The skin of the lip must be dissected off of the underlying orbicularis oris. Removal of a Burrow triangle from the vermilion is usually necessary to prevent excess bunching with approximation of the opposing borders of the two advancement flaps.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree