13 Reconstruction of male genital defects

Synopsis

This chapter deals with the following topics:

Basic science: genital embryology and anatomy

Genital embryology

Phenotypic sex

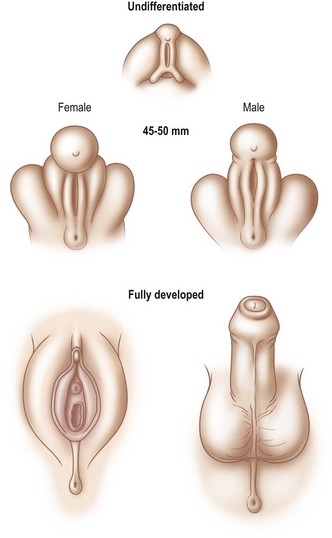

Phenotypic sex is ‘determined’ by whether the genital tubercle develops into a male or female pattern. In the male, urogenital swellings migrate ventrally and anteriorly to form the scrotum. The genital tubercle develops by elongation and cylindrical growth. At the same time, urethral folds close over the urethral groove, thereby establishing a urethra and a midline raphe. Mesenchymal tissue coalesces to surround the urethra and form the corpus spongiosum. This development is entirely under the influence (or absence) of testosterone, testosterone derivatives (i.e., dihydrotestosterone), and 5a-reductase and occurs between 6 and 13 weeks’ gestation (Fig. 13.1). The prepuce grows to cover the penile glans but is not influenced by dihydrotestosterone.

Genital anatomy

Genital fascia

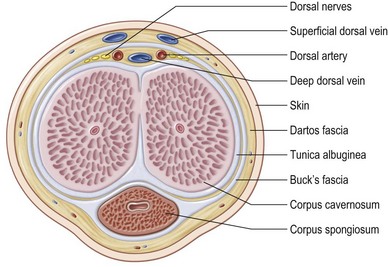

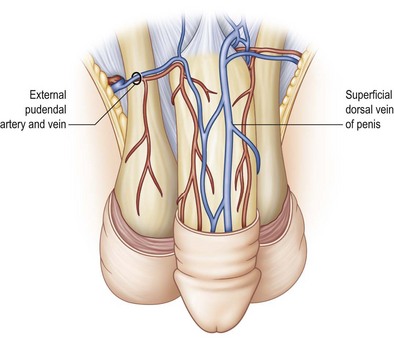

Overlying the tunica is the deep penile fascia (Buck fascia), a strong laminar structure that tightly surrounds and binds the corpora cavernosa together and, in the case of the corpus spongiosum, envelops these tissues into a single-functioning entity. The urethra and its overlying corpus spongiosum are also protected proximally by surrounding muscles and by their location within the intercorporal groove distally. Buck fascia carries important neurovascular structures to the glans penis, including the deep dorsal vein and arteries, the deep dorsal nerves of the penis, the circumflex arteries and veins, and the penile lymphatics (Fig. 13.2).1

Colles fascia is a deep, tight, triangular fascial system that arises laterally from the inferior pelvic rami and posteriorly from the perineal membrane to protect the genitalia from toxins, trauma, and infections (and envelops both testicles circumferentially, as the tunica dartos). Colles fascia is analogous to the dartos fascia on the penis, and thus skin island flaps can be elevated on the vascular plexus carried on this fascia (see Fig. 9.11).2

Genital blood supply

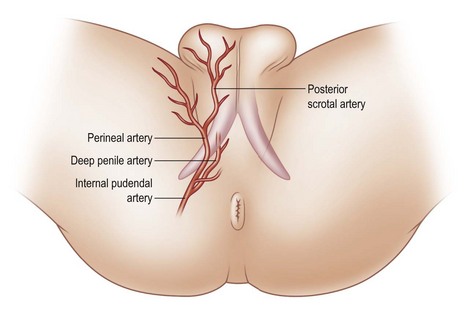

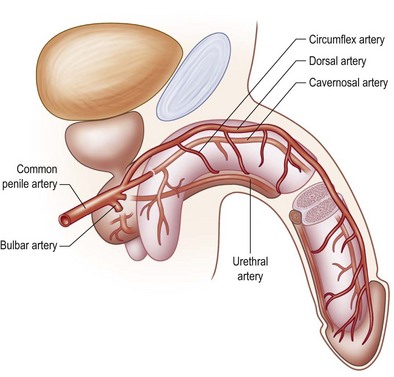

The genitalia have two separate arterial sources. The first is the deep vascular system originating from the deep internal pudendal artery. The paired pudendal arteries originate from the internal iliac arteries, pass along the borders of the inferior pelvic rami, and then give off the perineal and scrotal branches before continuing as the common penile arteries. After exiting from the Alcock canal, a split in the obturator fascia that runs from the lesser sciatic foramen to the ischial tuberosity along the sidewall of the ischiorectal fossa, each common penile artery gives off three branches (bulbar, urethral, cavernosal), and terminates in the dorsal artery of the penis, which runs within Buck fascia distally to terminate in the balanitic arteries. Within Buck fascia, the dorsal penile arteries are coiled and tortuous compared with the deep dorsal vein, which is linear and straight. This anatomy may have something to do with erectile function (Fig. 13.3).3

Fig. 13.3 The deep arterial vascularization to the penis arises from branches of the common penile arteries.

(From: Quartey JK. Microcirculation of penile and scrotal skin. Atlas Urol Clin North Am. 1997;5:1–9.)

The perineal branch of the pudendal artery is just superficial to Colles fascia and has an unpredictable length, but its central location and strong collateral supply make it a mainstay of genitourinary flap reconstruction. The scrotal branch of the perineal artery passes along the fold between the lateral scrotum and medial thigh and arborizes within the tunica dartos (Fig. 13.4).

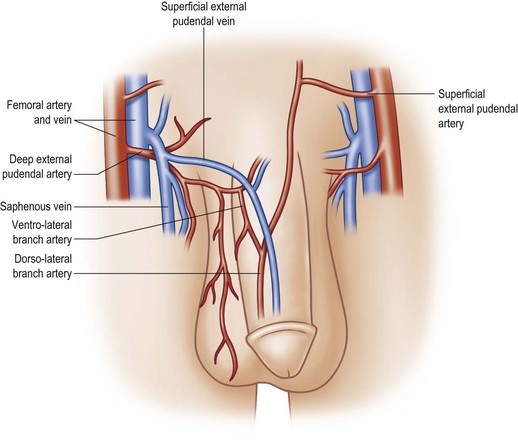

The second blood supply of the penis is the superficial external pudendal system –branches of the femoral arteries. The femoral artery typically gives off a superficial external pudendal artery and a deep external pudendal artery. The superficial external pudendal artery supplies vascularity to the dartos fascia and genital skin. The deep external pudendal artery arises as a separate branch and passes into the genital skin as the lateral inferior pudendal artery, which then separates into a dorsolateral branch supplying the dorsal and lateral penile shaft skin and an inferior branch supplying the ventral penile skin and the anterior plane of the scrotum (the anterior scrotal artery) (Fig. 13.5). This arrangement allows surgeons to elevate long axial and transverse flaps with relative safety and still cover the shaft donor site with the adjacent skin.

The penile venous system also has an accompanying dual blood supply. The superficial system arises from the distal penile shaft and passes to the superficial dorsal vein within the dartos fascia to drain the penile shaft skin. In approximately 70% of anatomic studies, the superficial dorsal vein empties into the left saphenous vein. Other vascular patterns include connections into the right saphenous vein (10%), left femoral vein (7%), and inferior epigastric vein (3%); in 10%, the deep dorsal vein runs as a dual supply and empties into the saphenous veins bilaterally. These collateral veins are usually of different caliber and are asymmetric in their course (Fig. 13.6).

The vas deferens, epididymis, and testes are vascularized from the retroperitoneal blood supply, primarily the spermatic artery, which originates from the aorta, and the deferential artery, which supplies the vas deferens. In addition, collateral blood supply from the retroperitoneal cremasteric artery follows the vas to become the vasal artery. As the spermatic artery and its venae comitantes approach the testis, it divides into the internal testicular artery (which supplies the testis and the adjacent epididymal head and body) and the inferior testicular artery, which passes within the testis. The epididymal tail is supplied by branches of the epididymal, vasal, and testicular arteries.4

Genital nerve supply

The nerve supply of the genitalia also arises from a dual source and runs concurrently with the arterial supply. The major sensory supply to the penis arises from the pudendal nerve in the perineum. The pudendal nerve is a mixed motor, sensory, and autonomic nerve that originates from the sacral roots (S2–S4). The nerve passes through the greater sciatic foramen and then courses anteriorly across the pelvic floor to enter the pudendal canal. Within the pelvis, the nerve gives off the inferior rectal nerve, supplying the rectal sphincter and anal skin and conducting the cavernosal reflex before entering Alcock (pudendal) canal. As the nerve exits Alcock canal and passes close to the crural tips of the corporal bodies, it divides into the perineal nerve and the dorsal nerve of the penis. The perineal nerve supplies the perineal muscles, deep structures of the urogenital region, and posterior scrotal skin. The dorsal nerve of the penis gives off a proximal nerve to the urethra before arborizing into its penile branches. Branches of the nerve pass around the penile shaft within Buck fascia to innervate the distal shaft and inner lamina of the prepuce as well as pass directly into the glans as the major tactile and erogenous source of the penis (see Fig. 9.18).

Congenital genital defects

Exstrophy and epispadias

The etiology of exstrophy-epispadias is controversial, but it does not represent an arrest of a normal fetal developmental stage. It occurs in early gestation between the 3rd and 9th weeks. The anomaly is associated with the formation and normal retraction of the cloacal membrane. In the normal fetus, a mesodermal layer of tissue spreads medially to replace the thin cloacal membrane by the 9th week in utero. According to Muecke’s theory,5 the cloacal membrane persists and resists any medial migration of mesoderm. The membrane then ruptures, thereby producing a lack of mesodermal tissue to form the anterior abdominal wall and endodermal tissue to form the anterior wall of the bladder. This lack of mesodermal migration also has a profound effect on the musculoskeletal system. The pubic rami are widely separated, and the inferior pubic rami are consequently laterally rotated. This defect produces a widened and foreshortened urethra and bladder neck. It also produces an incompletely formed penis that remains rudimentary and, by definition, is a phallus. According to Mitchell and Bägli,6 the anomaly is that of a fetal abdominal wall hernia and can be recreated in the laboratory in chickens because they have a persistent cloaca by induction of a localized vascular accident (J. Sumfest, pers. comm. 2002).

The defining features of exstrophy-epispadias are: an open urinary tract with protruding bladder and foreshortened epispadiac penis (Fig. 13.7). The crural bodies are attached to the splayed pubic tubercles, producing a penis that is short, wide, and with dorsal chordee. Unlike in the normal anatomy, corporal bodies are independent of each other with no communication through the intercorporal septum. The neurovascular structures to the glans are laterally displaced but move medially at the distal end of the foreshortened penis; the glans is spade shaped and incompletely formed, and each side is totally dependent on the respective dorsal neurovascular supply for its viability. Little circulation passes through the corporal bodies into the glans, as opposed to a penis with normal development. The separated pelvic ring also produces a widened scrotum and lack of competent pelvic musculature. Therefore, the perineum is short and the anus can be patulous and anteriorly displaced. The rectus muscles are widely separated, and inguinal hernias are the rule.

Different techniques have been described for penile reconstruction6,7 and although the results of the urethral closure have drastically improved, the ideal surgical approach is still controversial: neonatal versus delayed closure and one stage versus multi-stage repair. Phallic length mainly depends on antenatal development and the majority of these patients end-up with small and undeveloped penises, despite the best efforts of their treating surgeons. As they pass through their post-adolescent period, many of these young men will benefit from further lengthening procedures or even complete penile reconstruction. In some patients; correction of unaesthetic scars and further release of insufficiently released corpora can help to gain length (Fig. 13.8).

Exstrophy patients miss an umbilicus and often they are consulting for umbilical reconstruction. Different techniques have been described with good cosmetic outcomes. Neonatal preservation of the umbilicus and transposition to an abdominal position can overcome the loss of umbilicus.8,9

Unfortunately, in some boys there just is not enough tissue due to underdevelopment or due to partial or complete loss of penile tissue after primary closure. These patients might be a good candidate to undergo a phallic construction or further penile reconstruction with the use of microsurgical tissue transplantation techniques (Fig. 13.9) or local pedicled perforator flaps (see below, Fig. 13.12A–C).

Disorders of sex development (formerly “intersex”)

After standardization of the terminology, intersex conditions are nowadays defined as Disorders of Sexual Development (DSD).10

Buried penis

The buried penis deformity is present in both the pediatric and adult populations. A buried penis is defined as a penis that is of normal size for age but hidden within the peripenile fat and subcutaneous tissues (Fig. 13.10).

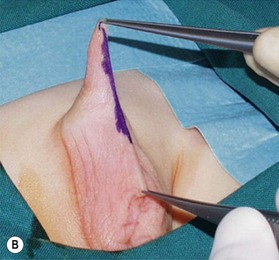

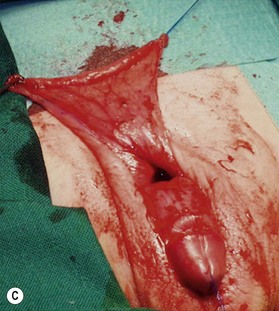

In the pediatric population, the fat deposit is often part of the constellation of poor virilization. The abnormal mons fat pad (gynecoid mons pubis) may become associated with a generalized obesity in the adolescent patient, and the buried penis must be differentiated from a micropenis in this group. In adults, the problem is almost always associated with obesity and the development of pubic, scrotal, and peripubic ptosis, which must be addressed to correct the problem of the hidden penis. Liposuction and lipectomy are part of the treatment in adults however in children the fat resection is abandoned. With pubertal development the prepubic fat deposit often decreases in size. The focus is on the release of the penis from the fibrotic dartos tissue.11,12 Many techniques are described but the most important steps include keeping all available skin from the start of the procedure, to resect all dartos tissue and to recover the released corpora with the skin (Fig. 13.11).

Reconstructive options for severe penile insufficiency

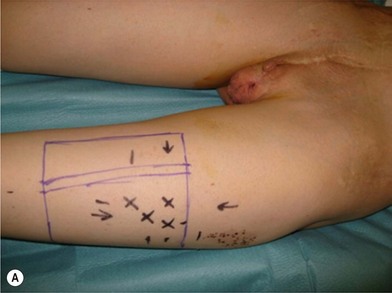

There are several reasons why in the ‘boys without a penis’ a pedicled ALT flap can be preferred above the standard radial forearm flap (Fig. 13.12):

• A pedicled flap reconstruction (the flap has a sufficiently long pedicle) avoids the technically more complex microscopic procedure and might also shorten the operation time.

• A visible donor site scar on the forearm, often considered as the signature of female-to-male transsexualism is avoided and the donor site on the leg can more easily be concealed.

• Previous reconstructive surgeries at the pelvis, groin area and lower abdomen (e.g., in case of bladder exstrophy) might have altered the local anatomy and vasculature making a microsurgical anastomosis more difficult.

• The subcutaneous fat layer is much thinner than in a (biologically female) transman, facilitating the (urethral)tube-within-a-(penile)tube reconstruction of the penis; moreover, many exstrophy patients empty their bladder by catheterization through a continent diversion (e.g., appendico-vesicostomy) and don’t even require a urethral reconstruction in their phalloplasty. An ejaculatory opening can be left at the ventral aspect just above the scrotum.

It is very important to preserve and incorporate any useful glandular, penile and cavernosal tissue at the basis of the newly reconstructed phallus in order to facilitate sexual stimulation and pleasure (Fig. 13.9C). If available, a dorsal penile nerve is identified and connected with a cutaneous nerve of the flap; if not available, the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is connected to the ilioinguinal nerve.

There is still a lot of controversy whether or not to perform a phalloplasty in children. Penile construction in children is similar as in adults with one added requirement – growth through puberty to adulthood. Because the phallus is constructed of somatic tissues (showing linear growth) but replaces a penis that is formed by genital tissues (demonstrating a more exponential growth), the growth rates are temporally and quantitatively different during puberty.13 Care must be taken to accurately predict the anticipated growth rate and to design a phallic model that is larger and longer than normal genital size for that age group.14