Psoriasis

James J. Herrmann

I. BACKGROUND

Psoriasis is a chronic proliferative epidermal disease with no cure. The cause is unknown. It affects up to 8 million people in the United States and 1% to 3% of the world’s population. Psoriasis typically begins in the third decade of life but can develop anytime from birth onward. A family history of psoriasis is found in 30% of affected patients. A multifactorial mode of inheritance is most likely. The histocompatibility antigen HLA-Cw6 is most strongly associated with psoriasis (relative risk is 24).

Psoriasis is due to a chronic T-cell-mediated inflammation within the psoriatic plaque. Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the skin are activated by unknown antigens and travel to the lymph nodes. In the lymph nodes, APCs in turn activate T cells and program these T cells to home back to the skin. Once in the skin, these activated T cells, APCs, and keratinocytes produce inflammatory cytokines including IL-12, 17, and 23, tumor necrosis factor-α, and IFN-γ causing epidermal hyperproliferation and the formation of the psoriatic plaque.

Hyperstimulated psoriatic keratinocytes travel from the basal cell layer to the surface in 3 to 4 days, much more rapidly than the normal 28 days. Decreased keratinocyte transit time does not allow for normal maturation and keratinization. This is reflected clinically by scaling, a thickened epidermis with increased mitotic activity, and by the presence of the immature nucleated cells in the stratum corneum.

II. CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Psoriasis is chronic and usually remains as discrete localized plaques in the majority of patients. Extensive or generalized involvement may occur in up to 25% of patients. Spontaneous clearing is rare, but unexplained exacerbation or improvement is common. Stress, viral (including HIV), or bacterial illness may precede flare-ups. Alcohol and smoking can also exacerbate the disease.

Most lesions of psoriasis are asymptomatic, but pruritus may be noted in up to 20% of patients. Those with generalized disease may resemble an exfoliative dermatitis with loss of thermoregulation leading to a feeling of chills and shivering, increased protein catabolism, and cardiac stress.

Up to 30% of patients may develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA). This is most commonly manifested by oligoarticular or polyarticular asymmetric joint pain in the small joints of the hands, feet, and spine. However, larger joints may be affected.

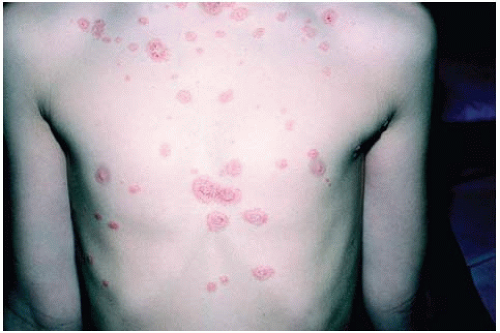

The classic psoriatic lesion is an erythematous, sharply circumscribed plaque covered by loosely adherent, silvery scales (Figs. 36-1 and 36-2). Acute lesions tend to be small and guttate (dewdrop shaped) (Fig. 36-3). Pinpoint bleeding can be seen when the scale is removed (Auspitz sign). Any body area may be involved, but lesions tend to occur most often on the elbow, knees,

scalp, genitalia, and intergluteal cleft. The lesions may also occur in areas of epidermal injury (the Koebner reaction) such as in scratches, scars, or sunburns.

scalp, genitalia, and intergluteal cleft. The lesions may also occur in areas of epidermal injury (the Koebner reaction) such as in scratches, scars, or sunburns.

Nail involvement (pitting, yellow-brown discoloration, subungual hyperkeratosis) can be seen in up to 50% of patients with psoriasis and in most patients with PsA of the hands and feet (Fig. 36-4).

Figure 36-5. Psoriasis. Erythrodermic variant. (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.) |

Exfoliative (erythrodermic) psoriasis resembles other exfoliative dermatoses. It may occur spontaneously, follow a systemic illness or drug reaction, or occur as a reaction to steroid withdrawal (Fig. 36-5).

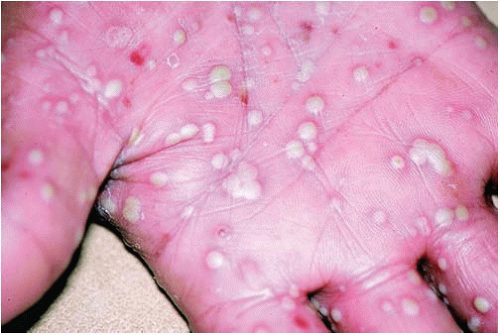

Pustular psoriasis occurs in several forms: acute (von Zumbusch), subacute annular, and chronic acral (Fig. 36-6). The pustules are sterile. Flare-ups may be precipitated by infection or recent use of systemic corticosteroids. Impetigo herpetiformis is a rare form of pustular psoriasis during pregnancy.

Figure 36-6. Psoriasis. This is the pustular variant of psoriasis. (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.) |

PsA is characterized by inflammation in and around the joints of the wrists, fingers, knees, ankles, lower back, and neck. It is equally common in both men and women with the age of onset typically between 30 and 55 years old. The rheumatoid factor is usually negative; 25% to 30% of psoriasis patients will develop PsA. It may appear up to 10 years after the first signs of skin involvement and in 85% of patients with PsA the skin disease precedes the arthritis.

PsA classically involves the distal interphalangeal joint and may be acute causing erythema and swelling of the distal phalanx causing a “sausage” appearance (dactylitis) (Fig. 36-7).

Fifty percent of patients have asymmetric oligoarticular disease (affecting less than or equal to four joints), 25% have symmetric disease, 25% have spondyloarthritis with or without peripheral arthritis, and 5% have a destructive polyarthritis (arthritis mutilans) (Fig. 36-8).

The CASPAR classification criteria are a very specific (98.7%) and sensitive (91.4%) way to diagnose PsA.3 Using the CASPAR system, a patient with inflammatory articular disease of the joints, spine, or tendons (enthesitis) plus a score of 3 or more points from the following supports the diagnosis of PsA (Table 36-1).

III. WORKUP

The diagnosis of psoriasis is mainly a clinical one. Preceding streptococcal pharyngitis is often the cause of acute guttate disease. Family history of psoriasis can be helpful.

Medications such as lithium, antimalarials, β-blockers, NSAIDs, and the statins have been implicated to cause flares. When in doubt, a skin biopsy may be helpful.

Patients with PsA typically have an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and a negative test for rheumatoid factor. X-ray films of the hands may show subcortical cystic changes with relative sparing of the articular cartilage.

Many patients have associated metabolic syndrome with obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

IV. TREATMENT

A. General Principles. When deciding on what therapy to begin with, it is important to involve the patient in the decision-making process. The treatment is usually chronic so the patient must be comfortable and compliant with the therapy to achieve success. Many psoriasis patients have other underlying medical problems including obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. These problems must be assessed in order to determine whether systemic treatment is appropriate. The extent of disease involvement may be limited, but if it is impairing the quality of life, a more aggressive systemic therapy may be warranted.

B. Basic Approach to Managing a Patient with Psoriasis. Below are some treatment suggestions for different types of patients. The clinician must use his/her clinical judgment as to the best approach to ultimately use.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree