Abstract

Pruritus is defined as an unpleasant sensation of the skin that elicits a desire to scratch, and it represents the most common skin-related symptom. In primary skin diseases, pruritus often accompanies the distinct skin lesions. In pruritus due to underlying systemic diseases (e.g. renal, hepatic, endocrine, hematologic, neoplastic, psychiatric) or drug intake, there may be no cutaneous signs or only secondary skin lesions due to scratching (e.g. prurigo nodularis, lichen simplex chronicus). This chapter provides an approach to the evaluation and treatment of patients with pruritus as a chief complaint. Regional forms of pruritus and dysesthesia are also reviewed, including those with neurologic etiologies. Although our incomplete understanding of the pathogenesis of pruritus has hampered therapeutic advances, recent discoveries provide hope for more effective treatments in the future.

Keywords

pruritus, renal pruritus, cholestatic pruritus, paraneoplastic pruritus, pharmacologic pruritus, prurigo nodularis, lichen simplex chronicus, neuropathic itch, dysesthesia, sensory mononeuropathy, notalgia paresthetica, brachioradial pruritus, meralgia paresthetica, psychogenic pruritus

Introduction

Pruritus can be defined as an unpleasant sensation that elicits a desire to scratch. The presumed biologic purpose of pruritus is to provoke scratching to remove a parasite or other harmful pruritogen. Pruritus is the most common skin-related symptom. It often arises from a primary cutaneous disorder but represents a manifestation of an underlying systemic disease in ~10–25% of affected individuals . Non-dermatologic conditions that can lead to generalized pruritus include hepatic, renal, or thyroid dysfunction; lymphoma, myeloproliferative neoplasms (e.g. polycythemia vera), and chronic lymphocytic leukemia; HIV or parasitic infections; and neuropsychiatric disorders (see Ch. 7 ).

Although there is no definitive categorization system for pruritus , a clinical classification scheme was proposed in 2007 by the International Forum for the Study of Itch . In this system, there are three major groups of pruritus: (1) affecting diseased (inflamed) skin; (2) affecting non-diseased (non-inflamed) skin; and (3) presenting with chronic secondary scratch-induced lesions (e.g. prurigo nodularis). Following initial evaluation, the etiology of the pruritus is categorized as dermatologic, systemic, neurologic, psychogenic, mixed, or other/unknown. This helps in planning further investigations and treatment of the underlying disease (if possible) as well as the pruritus itself. Although our incomplete understanding of the pathogenesis of pruritus (see Ch. 5 ) has hampered therapeutic advances, recent discoveries provide hope for more effective treatments in the future .

Epidemiology

It is assumed that all humans experience the sensation of pruritus at some point in their life, e.g. from insect bites ( Fig. 6.1 ). However, relatively few studies have investigated the overall incidence and prevalence of pruritus. A German population-based, cross-sectional study found that the self-reported point, 12-month, and lifetime prevalences of chronic pruritus (lasting ≥6 weeks) were 13.5%, 16%, and 22%, respectively . In a Norwegian population-based, cross-sectional study on self-reported skin morbidity, pruritus was the dominant symptom among adults, experienced within the past week by 9% of women and 7.5% of men . Table 6.1 summarizes the prevalences of pruritus in various medical conditions .

| PREVALENCE OF PRURITUS IN SELECTED CONDITIONS | |

| Disorder | Reported prevalence of pruritus |

| Atopic dermatitis | 100% (diagnostic criterion) |

| Lichen planus | ~95% |

| Psoriasis | ≤85% |

| End-stage renal disease on hemodialysis | 25–30% (previously 60–80%) |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 80% (presenting symptom in 25–70%) |

| Hepatitis C viral infection | 15% |

| Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma | 60–80% overall; >90% in Sézary syndrome |

| Polycythemia vera | 30–50% |

| Hodgkin disease | 15–30% |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 2–10% |

| Leukemias | <5% |

| Herpes zoster | ≤60% |

| Postherpetic neuralgia | ≤30% |

| Pregnancy | 20% |

Evaluation of the Patient

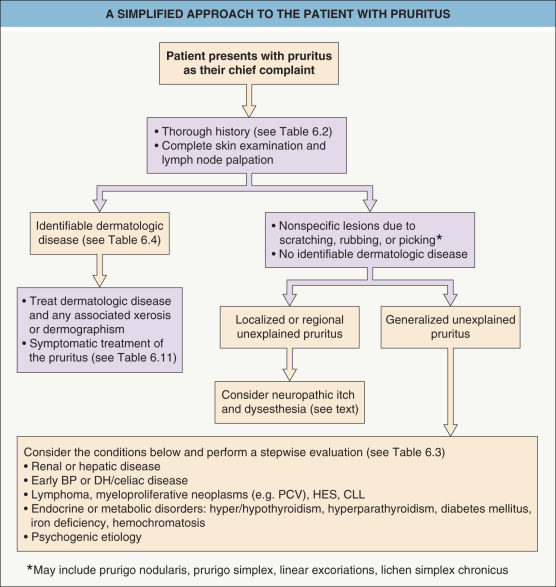

A structured approach to the evaluation of patients with a chief complaint of pruritus is presented in Fig. 6.2 . Pruritus is a subjective sensation, and currently its presence or severity cannot be assessed objectively. Thus, a thorough history that includes the patient’s itch sensation plus a complete cutaneous examination for any evidence of skin lesions are important for correct diagnosis and allow assignment of the patient to one of the three groups of pruritus (see above). Patients with evidence of a particular skin condition should be treated accordingly, while those with no identifiable primary skin disease (i.e. an absence of or only secondary skin lesions) require further investigation to determine the etiology of their pruritus. Also, chronic pruritus can have multiple underlying factors, and a pruritic skin condition that has nonspecific clinical findings initially may over time develop diagnostic features. Therefore, longitudinal evaluation is essential.

History

A precise history may provide insight into the patient’s disease processes. In addition to the patient’s spontaneous description, specific questions regarding the onset, location, duration, and nature of the pruritus can help to determine its cause ( Table 6.2 ). Although chronic, progressive, generalized pruritus without primary skin lesions raises suspicion of an underlying systemic disease, no particular clinical characteristics reliably predict the likelihood of a systemic etiology.

| DESCRIPTIVE FEATURES OF THE PRURITUS AND ADDITIONAL PATIENT HISTORY |

| Questions to ask regarding the pruritus |

|

| Additional patient history |

|

Examination

Careful and complete examination of the skin, nails, scalp, hair, mucous membranes (e.g. oral, conjunctival), and anogenital area at the initial visit is recommended. The morphology and distribution of primary lesions and secondary changes (e.g. excoriations, crusts) should be assessed, with particular attention to xerosis, the presence of dermographism ( Fig. 6.3 ), and skin signs of systemic diseases (see Ch. 53 ). Lesions on the mid upper back suggest a primary skin disease, since this difficult-to-reach area is typically spared (the “butterfly sign”) in patients with skin lesions due entirely to scratching (see Fig. 6.5A ). However, this region can be accessed with “back-scratching” devices.

The examination should include palpation of major peripheral lymph node groups (e.g. cervical, supraclavicular, axillary, inguinal), especially in those with no obvious primary inflammatory skin disease. Together with a general physical examination performed by the patient’s primary care physician, this may disclose an undiagnosed extracutaneous disease (e.g. lymphoma) in individuals with pruritus of unknown etiology.

Laboratory Investigation

In the setting of pruritus of unknown etiology, a stepwise approach to laboratory tests and other investigations (e.g. radiographic) is recommended ( Table 6.3 ). Microscopic examination of skin scrapings for signs of scabies or a fungal infection can also be considered. Biopsies of representative skin lesions, even if nonspecific clinically, are occasionally informative, and direct immunofluorescence studies of perilesional skin or normal-appearing skin (in the vicinity of lesions if present) may point to a specific dermatologic disease such as bullous pemphigoid or dermatitis herpetiformis, respectively.

| LABORATORY AND RADIOGRAPHIC EVALUATION IN PATIENTS WITH PRURITUS OF UNKNOWN ETIOLOGY |

| Basic initial evaluation |

|

| Possible additional evaluation |

Skin biopsy

Other laboratory tests

Radiographic studies

Other investigations

|

* Biopsy perilesional skin or normal-appearing skin (in vicinity of lesions if present) to assess for bullous pemphigoid and dermatitis herpetiformis, respectively.

** Often performed in conjunction with serum total IgA; in patients with IgA deficiency, anti-tissue transglutaminase IgG antibodies should be assessed.

Pruritus in Dermatologic Disease

This section focuses on the sensation of pruritus in selected skin diseases where this symptom is a prominent feature. A more comprehensive discussion of the diseases mentioned and the many additional dermatoses in which pruritus is a characteristic feature ( Table 6.4 ) may be found in other chapters.

| PRIMARY DERMATOLOGIC CONDITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH PRURITUS | |

|---|---|

| Cause | Dermatologic disease |

| Inflammation |

|

| Infestation/bites & stings |

|

| Infections |

|

| Neoplastic |

|

| Genetic/nevoid |

|

| Other |

|

Inflammatory Dermatoses

Urticaria

Urticaria is often intensely pruritic and can also produce stinging or prickling sensations. Early lesions and small superficial wheals are particularly symptomatic . Histamine plays a primary role in the pruritus of urticaria, and H1-receptor antagonists usually decrease or eliminate this sensation as well as the wheals themselves (see Ch. 18 ).

Atopic dermatitis

Pruritus is such an important aspect of atopic dermatitis that “the diagnosis of active atopic dermatitis cannot be made if there is no history of pruritus” (see Ch. 12 ). The itch sensation typically comes in “attacks”, which may be severe and significantly impact quality of life . Often, pruritus is the first indication of a disease flare. In patients with atopic dermatitis, pruritus can be provoked by exposure to aeroallergens or ingestion of foods to which the patient is sensitized as well as non-immunologic triggers, including emotional stress, overheating, perspiration, and contact with rough fabrics or even air (atmokinesis) ( Fig. 6.4 ). Although most affected children experience worsening of symptoms during the winter, others have exacerbations primarily during the summer .

The minimal effectiveness of antihistamines in alleviating the itch of atopic dermatitis indicates that histamine is probably not the predominant mediator of the pruritic sensation . Rather, the benefit of antihistamines in atopic dermatitis is most likely due to their sedative effects. Other mediators and receptors with possible roles in the pruritus of atopic dermatitis include neuropeptides (e.g. substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide [CGRP]), neurotrophic factors (e.g. nerve growth factor [NGF], artemin [causes warmth-provoked itching]), thymic stromal lymphopoietin, epidermal opioid receptors (down-regulated), interleukin (IL)-2, IL-31, endothelin-1, and mast cell tryptase binding to protease-activated receptors (PAR-2) (see Ch. 5 ). In atopic patients, epidermal hyperinnervation and central sensitization may also contribute to an increased itch sensation and even the perception of painful stimuli as itch . In recent randomized placebo-controlled studies, subcutaneous injection of the anti-IL-31 receptor A antibody nemolizumab significantly reduced itch and improved sleep in adults with atopic dermatitis .

Psoriasis

Although not traditionally regarded as a pruritic disease, studies have shown that up to 85% of psoriasis patients suffer from pruritus, with xerosis, heat, sweating, and emotional stress serving as exacerbating factors . In general, lesions on the back, extremities, buttocks, and abdomen are the most pruritic, although scalp itch predominated in a study of hospitalized patients . Generalized pruritus occasionally occurs in plaque-type psoriasis as well as in erythrodermic and pustular psoriasis. Patients frequently describe the pruritus as having tickling, crawling, and burning components, and antihistamines rarely provide relief . A variety of itch mediators (e.g. substance P, nerve growth factor, IL-2) may be present in psoriatic skin, suggesting complex, multifactorial pathophysiology .

Infestations

Scabies

In patients with scabies, pruritus can be localized or generalized, and it may have a burning component. The pruritus usually begins 3–6 weeks after a first-time infestation, and within a few days in subsequent infestations; multiple family members are often affected (see Ch. 84 ). The itch reflects various components of the immune response against mites, eggs, and scybala .

Pediculosis (lice)

Pruritus at the primary sites of infestation (e.g. scalp, groin) is a clue to the diagnosis of head and pubic lice (see Ch. 84 ). Generalized pruritus is characteristic of body lice but can also occur with other forms of lice infestation .

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma (CTCL)

Pruritus affects >60% of patients with CTCL, with an increased frequency and intensity in those with later-stage disease, especially Sézary syndrome (>90% of patients) and folliculotropic mycosis fungoides (MF) . A variant of Sézary syndrome presenting with generalized pruritus and minimal or no clinically evident skin disease has also been described . Pruritus significantly reduces the quality of life in CTCL patients and has been associated with increased risk of disease progression and death .

Recent evidence implicates IL-31 as a putative mediator of itch in CTCL, especially late-stage disease, and lower serum IL-31 levels have been observed in association with reduced pruritus following treatment with histone deacetylase inhibitors and mogamulizumab (anti-CC-chemokine receptor type-4 antibody) . Treatment strategies for severe pruritus not responsive to disease-directed therapy in CTCL patients include gabapentin (900–2400 mg daily in divided doses) and/or mirtazapine (7.5–15 mg nightly) as well as opioid antagonists (e.g. naltrexone 50–150 mg daily) . Aprepitant has also been reported to relieve intractable pruritus in patients with Sézary syndrome and other forms of CTCL, suggesting a role for NK1 receptors and substance P in CTCL-related itch .

Dermatoses Induced by Pruritus-Associated Scratching or Rubbing

Prurigo Nodularis

In prurigo nodularis, secondary skin lesions are produced by chronic, repetitive, focused scratching or picking of the skin. The nodules themselves are intensely pruritic, leading to the induction of an itch–scratch cycle. Prurigo nodularis is primarily a disease of adults, especially middle-aged women. It occasionally occurs in children and adolescents, especially those with an atopic diathesis.

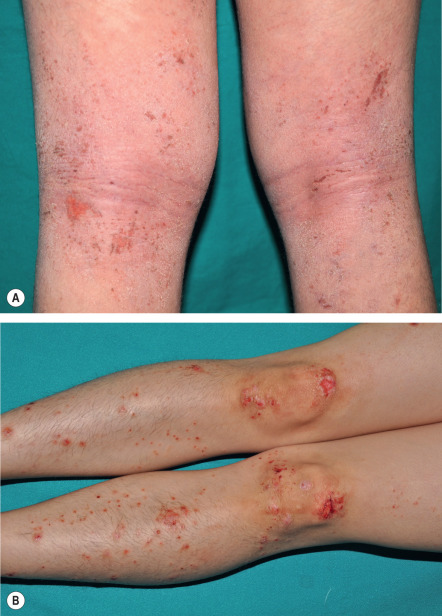

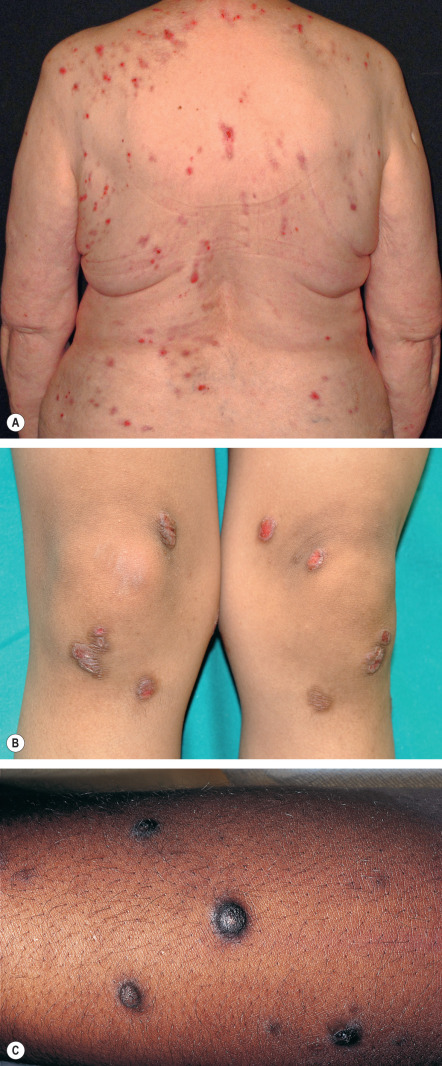

Multiple lesions are characteristically distributed symmetrically on the extensor aspects of the extremities. The upper back, lumbosacral area, and buttocks may also be involved, but the difficult-to-reach mid upper back is classically spared (“butterfly sign”) ( Fig. 6.5A ). Flexural areas, the face, and the groin are usually not affected.

The basic lesion is a firm, dome-shaped papulonodule with varying degrees of central scale, crust, erosion, or ulceration ( Fig. 6.5A–C ). The color ranges from skin-toned to erythematous to brown, and hyperpigmentation is particularly common in dark-skinned individuals (see Fig. 6.5C ). Lesions can develop a verrucous or fissured surface, and lichenification of adjacent skin may be observed. When crusts, but not clear-cut papulonodular lesions, are present, the term prurigo simplex is sometimes utilized.

Many patients with prurigo nodularis have pruritus due to atopic dermatitis, xerosis, another dermatologic condition, or a systemic disease (e.g. hepatic or renal dysfunction, hyperthyroidism, lymphoma). The underlying process may also be psychological, with emotional distress, obsessive–compulsive disorder, depression, or other psychiatric conditions leading to repetitive scratching. The clinical differential diagnosis of prurigo nodularis may include perforating disorders (e.g. acquired perforating dermatosis), pemphigoid nodularis ( Fig. 6.6 ), hypertrophic lichen planus, hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, scabietic nodules, persistent insect bite reactions, the pruriginous type of dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, and neoplasms such as multiple keratoacanthomas or granular cell tumors.

Histologically, prurigo nodularis features marked epidermal hyperplasia and thick, compact hyperkeratosis . Keratinocyte atypia is absent, and small areas of erosion may be seen. Fibrosis of the papillary dermis with vertically arranged collagen fibers, increased numbers of fibroblasts and capillaries, and a perivascular or interstitial mixed inflammatory infiltrate represent additional findings.

Possibly as a result of intense scratching, prurigo nodularis lesions demonstrate hypertrophy and an increased density of dermal nerve fibers. Although only occasionally evident with routine staining, this can be highlighted by immunostaining for a pan-neuronal marker such as protein-gene product 9.5 (PGP-9.5). In contrast, the number of nerve fibers within the epidermis is reduced. There is increased expression of substance P, CGRP, and NGF receptors by the dermal nerve fibers and prominent NGF immunoreactivity in lesional dermis. The dermal neuronal hyperplasia and epidermal “small fiber neuropathy” may play a pathogenic role in perpetuating the pruritus of prurigo nodularis .

Treatment of prurigo nodularis is usually difficult and typically requires a multifaceted approach, which should be individualized depending on etiologic factors and the extent of disease. Any underlying conditions (e.g. atopic dermatitis, chronic renal failure, cholestasis) should be identified and treated if possible. Ideally, significantly reducing the pruritus would break the itch–scratch cycle, eventually leading to healing of the lesions; however, this is often not possible, especially when there is a psychological underpinning. Topical antipruritic agents (e.g. menthol, pramoxine, polidocanol, palmitoylethanolamine) and oral antihistamines may help to decrease itch intensity. The former can be applied repeatedly as a “substitute” for scratching, and a sedating antihistamine at bedtime may be beneficial for sleep disturbances.

The skin lesions may respond to superpotent topical corticosteroids under occlusion, intralesional corticosteroids, phototherapy (e.g. narrowband or broadband UVB, psoralen plus UVA [PUVA]), or excimer laser treatment. Other topical treatments with potential benefit include capsaicin (0.025–0.3% 4–6 times daily, applied locally), calcipotriene (calcipotriol), and calcineurin inhibitors.

Treatment directed toward any underlying compulsive behavior is important. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants have both been employed successfully, especially when a component of depression is present. Doxepin can be particularly useful because of its antihistaminic, sedating, and antidepressant properties. Thalidomide (50–200 mg daily) has been reported to be highly effective for patients with recalcitrant prurigo nodularis , although its use is limited by teratogenicity and the potential side effect of peripheral neuropathy. Improvement with gabapentin, pregabalin, and the neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptor antagonist aprepitant has also been described . Use of µ-opioid antagonists (naloxone or naltrexone) or the combined µ-opioid antagonist/κ-opioid agonist butorphanol (intranasal) could represent additional options for recalcitrant disease . Cyclosporine may be of benefit, especially in patients with underlying atopic dermatitis, and successful treatment of prurigo nodularis with methotrexate has been reported.

Lichen Simplex Chronicus

In lichen simplex chronicus (LSC), there is epidermal hypertrophy secondary to chronic, habitual rubbing or scratching of localized areas of skin. Lesions of LSC are broader and thinner than those of prurigo nodularis. LSC is most frequently observed in adults and is relatively uncommon in children, with the exception of lichenified lesions in atopic dermatitis.

LSC is characterized by well-defined plaques exhibiting exaggerated skin lines (lichenification) with a “leathery” appearance, coalescing papules, hyperpigmentation, and varying degrees of erythema. Lesions may be solitary or multiple, with a predilection for the posterolateral neck, occipital scalp, anogenital region (e.g. scrotum, vulva), shins, ankles, and dorsal aspects of the hands, feet, and forearms ( Fig. 6.7 ). Predisposing factors include xerosis, atopy, psoriasis, stasis dermatitis, anxiety, obsessive–compulsive disorder, localized neuropathic itch, and pruritus related to systemic disease.

The clinical differential diagnosis may include lichen amyloidosis and hypertrophic lichen planus, both of which present with chronic pruritic plaques favoring the shins. Lichen ruber moniliformis is a historic condition that presents with cord-like fibrotic bands, which may be both pruritic and painful. Histologic features of LSC are similar to those of prurigo nodularis (see above), with compact hyperkeratosis, acanthosis with irregular elongation of rete ridges, hypergranulosis, and vertically oriented collagen bundles in the papillary dermis.

Like prurigo nodularis, lesions of LSC itch spontaneously, which leads to an “itch–rub/scratch–itch” cycle that often makes it resistant to treatment. Underlying pruritic disorders should be identified and treated if possible. Management strategies are similar to those described for prurigo nodularis (see above), with topical corticosteroids (±occlusion) and intralesional corticosteroids as the mainstays of therapy. Repeated application of a hydrocolloid dressing can lead to improvement. Informal insight-oriented psychotherapy and application of topical antipruritic agents as “substitutes” for rubbing/scratching may be of benefit. Use of topical lidocaine 5% or capsaicin 8% patches, licensed for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia, may be helpful in recalcitrant cases .

Pruritus in Specific Locations

Scalp Pruritus

Skin disorders involving the scalp (e.g. seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, folliculitis, lichen planopilaris, dermatomyositis) may present with pruritus localized to this area. However, scalp pruritus also occurs in the absence of any objective changes, most commonly in middle-aged individuals during periods of stress and fatigue . In such instances, treatments such as topical corticosteroids and antipruritic agents have been employed with inconsistent efficacy .

Anogenital Pruritus

Pruritus ani

Pruritus localized to the anus and perianal skin occurs in 1–5% of the general population, with a male : female ratio of ~4 : 1 . The onset is typically insidious, and symptoms may be present for weeks or years before patients seek medical attention.

Pruritus ani can be primary (idiopathic) or secondary in nature. Primary pruritus ani is defined as pruritus in the absence of any apparent cutaneous, anorectal, or colonic disorder; it accounts for 25–95% of reported cases, depending upon the series. Possible causes include dietary factors such as excessive coffee intake, poor personal hygiene, and psychiatric disorders. Secondary pruritus ani has an identifiable etiology such as chronic diarrhea, fecal incontinence/anal seepage, hemorrhoids, anal fissures or fistulas, rectal prolapse, primary cutaneous disorders (e.g. psoriasis, lichen sclerosus, seborrheic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis), sexually transmitted diseases, other infections, infestations (e.g. pinworms), previous radiation therapy, and neoplasms (e.g. anal cancer) . Pruritus ani (as well as pruritus vulvae or scroti) can also be neuropathic in origin and be due to compression or irritation of lumbosacral nerves from prolapsed intervertebral discs, vertebral body fractures, or osteophytic processes.

Findings on physical examination range from normal-appearing skin or mild perianal erythema to severe irritation with crusting, lichenification, and erosion or ulceration. Histologically, a nonspecific, chronic dermatitis is usually seen, but specific dermatoses (e.g. lichen sclerosus) and neoplastic disorders (e.g. extramammary Paget disease) can be excluded.

Evaluation includes a thorough history, complete cutaneous and general physical examination, and psychiatric screening. The latter is of importance considering that anxiety and depression may be aggravating factors for pruritus ani. Patch testing should be considered to exclude allergic contact dermatitis. Rectosigmoidoscopy and/or colonoscopy may be necessary, especially in patients with recalcitrant pruritus ani, in order to detect underlying conditions ranging from hemorrhoids to cancer . The possibility of pinworm infection should be considered, particularly in affected children. In patients receiving chronic antibiotic therapy who have liquid stools with a pH of 8–10, Lactobacillus replacement therapy is recommended.

While secondary pruritus ani usually improves with treatment of the underlying disorder, management of primary disease can be very challenging. Mild cases often respond to sitz baths (e.g. with astringents such as black tea), cool compresses, and meticulous hygiene using water-moistened, fragrance-free toilet paper or a bidet. The area is then dried with blotting or a fan, with avoidance of rubbing and alkaline soaps (see Ch. 153 ). Application of zinc oxide paste can help to protect the skin from further irritation and friction.

A mild corticosteroid cream (class 6 or 7) is often effective in controlling symptoms. However, with greater disease severity or the presence of lichenification, more potent topical corticosteroids and prolonged treatment may be required, raising the risk of cutaneous atrophy. Topical calcineurin inhibitors, including use on a rotational basis with topical corticosteroids, may be helpful when longer courses of therapy are necessary.

Pruritus vulvae and scroti

These common disorders, which may be incapacitating and emotionally disturbing, are solely psychogenic in only 1–10% of patients . Like pruritus ani, patients with pruritus of the vulva or scrotum typically complain of symptoms that are worse at night, and repeated rubbing or scratching leads to lichenification. The evaluation, differential diagnosis, and treatment options are similar to those for pruritus ani.

Acute pruritus of the vulva or scrotum is often related to infections such as candidiasis, but allergic or irritant contact dermatitis should also be considered. Chronic pruritus in these sites may be caused by dermatoses (e.g. psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, lichen sclerosus, lichen planus), malignancy (e.g. extramammary Paget disease, squamous cell carcinoma), or atrophic vulvovaginitis . Scrotal pruritus secondary to lumbosacral radiculopathy has also been described . In general, irritation related to cleansing and toilet habits needs to be addressed, as well as treatment of any identifiable underlying cause.

Pruritus Variants

Aquagenic Pruritus

Aquagenic pruritus is usually secondary to a systemic disease (e.g. polycythemia vera) or another skin disorder (e.g. urticaria, dermographism; Table 6.5 ), whereas primary (idiopathic) aquagenic pruritus is relatively uncommon. Aquagenic pruritus presents with prickling, tingling, burning, or stinging sensations within 30 minutes of water contact, irrespective of its temperature or salinity, and lasts for up to 2 hours . Typically, symptoms begin on the lower extremities and then generalize, with sparing of the head, palms, soles, and mucosae ; on examination, specific skin lesions are not seen. The pathologic mechanism is unknown, although elevated dermal and epidermal levels of acetylcholine, histamine, serotonin, and prostaglandin E 2 have been described .

| DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF PRURITUS OR PRICKLING SENSATIONS PROVOKED BY WATER CONTACT |

| Disease-associated skin findings typically evident at time of visit |

|

| Urticaria by history and/or challenge |

|

| Skin findings (other than those due to scratching) typically absent |

|

* Aspirin doses up to 300–500 mg 1–3 times daily may provide partial relief; improvement of aquagenic pruritus with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) has been reported.

Traditional therapy for aquagenic pruritus is alkalization of bath water to a pH of 8 with baking soda. Treatment with narrowband or broadband UVB or PUVA can be effective, with PUVA appearing to be superior to broadband UVB . Capsaicin cream (0.025–0.1%) applied 3–6 times daily for ≥4 weeks can decrease symptoms, but long-term use may not be practical . Systemic treatments such as oral cyproheptadine, cimetidine, and cholestyramine have shown minimal effectiveness . In secondary forms of aquagenic pruritus, treatments targeting the underlying condition may be beneficial, e.g. antihistamines for dermographism.

Pruritus in Scars

Scar remodeling can last from 6 months to 2 years. Pruritus associated with wound healing is common and usually resolves over time, but it is occasionally prolonged, especially in hypertrophic or keloidal scarring. The pruritus in immature or abnormal scars is most likely a consequence of physical and chemical stimuli as well as nerve regeneration. Physical stimuli include direct mechanical stimulation of nerve endings during scar remodeling. Histamine, vasoactive peptides (e.g. kinins), and prostaglandins E1/E2 may account for a “chemogenic” pruritus. Nerve regeneration occurs in all healing wounds, and a disproportionate number of thinly myelinated and unmyelinated C-fibers in immature or abnormal scars may contribute to increased itch perception. The observation of abnormalities in small nerve fiber function within keloids has raised the possibility of a small nerve fiber neuropathy .

Therapy includes emollients, topical and intralesional corticosteroids, and silicone gel sheets. Oral antihistamines do not have a significant benefit. Relief of pain and pruritus associated with giant keloids was observed with oral pentoxifylline (400 mg 2–3 times daily) .

Post-Thermal Burn Pruritus

Approximately 85% of patients with burns experience pruritus during the healing phase, particularly when the burns involve the limbs . A gradual decrease in pruritus usually occurs, but it may persist for years. Reported predictors of pruritus include a deep dermal burn injury, female gender, and psychological distress . Morphine therapy may also contribute to postburn pruritus. Emollients, topical anesthetics (e.g. lidocaine/prilocaine), massage therapy, and bathing in oiled water or with colloidal oatmeal may be of benefit . In a randomized controlled trial, oral gabapentin was found to be more effective than cetirizine for postburn pruritus .

Fiberglass Dermatitis

Fiberglass exposure is common in individuals who work in manufacturing or construction, and it may provoke severe pruritus, sometimes in the absence of visible skin lesions (see Ch. 16 ). Involvement of the hands and other noncovered sites such as the arms, face, and upper trunk is typical. Cutaneous findings may resemble scabies, eczematous dermatitis, folliculitis, or urticaria.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree