Pruritus

Vicky Ren

Suneel Chilukuri

I. BACKGROUND

Pruritus, or itch, is a sensation that leads to scratching. It can be acute or chronic (lasting more than 6 weeks), localized or generalized, and is broadly categorized neuroanatomically as pruritoceptive, neuropathic, neurogenic, or psychogenic. Itch is the most common symptom in many inflammatory skin diseases (e.g., atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, and psoriasis) and infectious skin diseases (e.g., chickenpox), but it may also be associated with systemic diseases (e.g., chronic renal failure, HIV, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) or simply xerosis. Because it is a subjective experience that is associated with a variety of conditions, it is difficult to estimate the incidence and prevalence of pruritus.

II. CLINICAL PRESENTATION

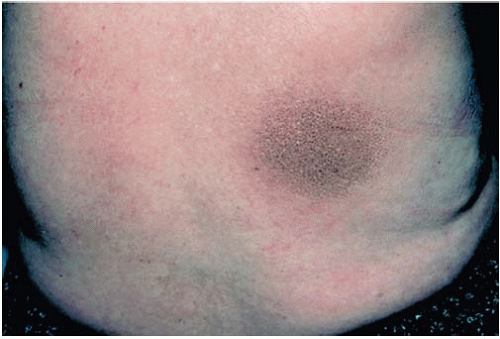

Pruritus provokes patients to scratch or rub their skin, which serves to potentiate the vicious scratch-itch cycle. Consequently, areas of itching may eventually manifest as areas of bleeding, excoriations, ulcerations, and crusts. Further scratching results in lichenification with changes in skin pigmentation as well as scar formation. Chronic pruritus may lead to hyperpigmented plaques and excoriated nodules resembling prurigo nodularis (Figs. 35-1, 35-2, 35-3) (Table 35-1).

III. WORKUP

Pruritus is a subjective perception described by the patient. In order to properly treat pruritus, the underlying cause must be elicited through a thorough history, physical examination, and a diagnostic workup. History should include location, onset, timing, duration, and character of the itch, as well as alleviating/aggravating factors and patient characteristics (e.g., age, medications, allergies, and signs of systemic disease). In addition to careful examination of the skin, nails, scalp, hair, and mucous membranes, a physical examination should also include palpation of lymph nodes, thyroid gland, and abdomen. Initial laboratory investigations should include a complete blood count with differential, as well as liver, renal, and thyroid function tests and urinalysis. Additional tests, such as anemia analysis, HIV, chest x-ray, and abdominal ultrasound, may also be necessary (Table 35-2).

IV. TREATMENT

Treatment of pruritus is aimed at relieving symptoms, eliminating the cause, and breaking the itch-scratch cycle. Generally, topical medications are used for mild, localized itch; systemic therapies may be necessary for severe, generalized itch. Many patients require a combination (Table 35-3). Regardless of treatment option, it is important to offer patients practical advice consistent with eczema skin care, such as limiting shower time, bathing in lukewarm water, keeping fingernails short, and using mild cleansers.

A. Topical Treatments. Topical therapy is important in the management of acute pruritus as well as more generalized pruritus in patients who may not be candidates for systemic therapy.

1. Moisturizers. Moisturizers alleviate itching by improving the barrier function of the skin, specifically by controlling transepidermal water loss. They are of proven benefit in xerosis, atopic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, and psoriasis and may be beneficial to all patients suffering from pruritus. Patients should be advised to apply moisturizers one to three times daily and especially after bathing. Generally, thick creams with high lipid content are preferred to thinner lotions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree