Chapter 33 Progressive tension sutures in abdominoplasty

• Progressive tension sutures (PTS) is a simple suture technique for advancement and fixation of a flap that is ideal for use in abdominoplasty.

• Seromas are eliminated by decreasing dead space as well as fixing the flap to avoid movement-related disruption of early healing, without the need for drains.

• Other benefits include reduction of complications, early upright ambulation and a quicker, easier recovery.

• PTS can be added to any abdominoplasty procedure.

• It is an easy to learn technique and once learned, there is minimal time added, but a very high degree of patient satisfaction.

Introduction

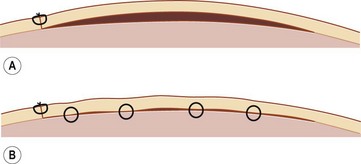

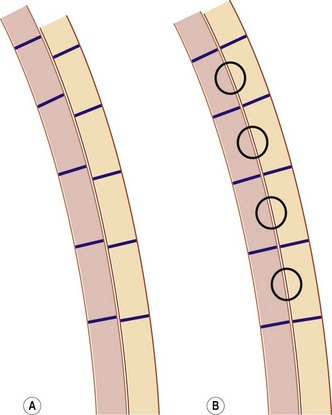

Progressive tension sutures (PTS) is a technique for advancing and securing a flap.1,2 Since it is not an abdominoplasty procedure in itself, PTS can be adapted to the surgeon’s personal abdominoplasty operation. PTS is used to decrease complications in abdominoplasty, especially seroma, while eliminating the need for drains. The mechanism of these sutures is to close dead space (Fig. 33.1), as well as, and maybe more importantly, to secure the skin flap to the underlying fascia to prevent disruption of early healing by abdominal motion (Fig. 33.2). Additionally, these sutures transfer the tension of the advancement over a broad area to the superficial fascial system and away from the skin, improving blood flow in the subdermal plexus and taking tension off the skin closure, to improve scarring. The secure fixation of the flap permits early ambulation in an upright posture, which likely decreases pulmonary and venothromboembolic (VTE) complications. What follows are details of the authors’ abdominoplasty technique, which details the use of PTS.

Surgical Technique

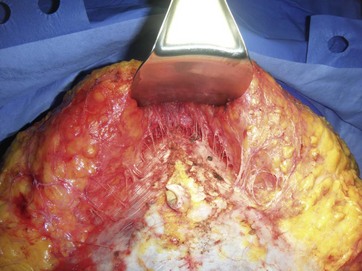

The circumumbilical incision is made within the umbilicus and the stalk is dissected down to the deep fascia. Next, the low transverse suprapubic incision is made and carried down to the muscle fascia. No attempt is made to leave fat on the fascia except for a few centimeters in the central area where bulk may be needed later to help with the esthetic transition from the thinner upper abdominal flap to the thicker mons pubis. Dissection is carried out both sharply and with electrocautery. We have not seen any increase in seromas with extensive electrocautery use. The technique and extent of dissection is based on the surgeon’s judgment and the individual patient’s anatomical characteristics. We use a triangular dissection, which is wider inferiorly and narrowest at the level of the xiphoid, but is individualized based on the width of rectus diastasis and extent of soft tissue to be advanced (Fig. 33.3).

The fascia is then generously infiltrated with a long-acting local anesthetic for early postoperative pain control. In patients with wide diastasis recti, we often will place a continuous double-catheter pain pump with an infusion rate of 2 ml/hr per catheter. We bring the catheters out at the level of the xiphoid and use the introducers in a retrograde fashion (from inside to out) so they can be re-used for a retrofascial placement. The functional portions of the catheters are placed under the rectus fascia on either side of the umbilicus (Fig. 33.4A–C).

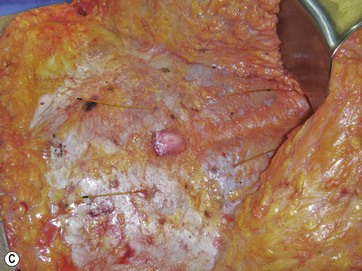

When a ptotic mons pubis is present, correction is important for a good esthetic result. The mons is undermined as needed and a few 2-0 Vicryl sutures are placed from the underside of the mons to the desired position on the deep fascia. Typically only three sutures are needed – one midline and one on either side, with 3–4 cm spacing. Care is taken to leave the edge of Scarpa’s fascia free for later suturing to the upper flap. Advancement to an appropriate position with secure fixation with progressive tension sutures gives the mons an attractive appearance and prevents unintentional excessive elevation by flap retraction (Fig. 33.5).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree