• Preoperative evaluation must include assessment of nasal function as well as aesthetic goals.

• Each approach should be individualized to the patient. Surgical planning must take into consideration form, function, age, gender, and ethnic background.

• Computer imaging and preoperative photographs facilitate discussion between the surgeon and the patient regarding surgical goals.

• The patient should be counseled extensively on the risks of postoperative recovery. Patients must also be aware the postoperative edema can take up to 3 years to resolve.

• When indicated, autologous cartilage grafting is preferred. Alloplastic materials carry the risk of infection and extrusion. Fillers should also be avoided due to the risk of ischemic necrosis.

Introduction

Rhinoplasty is widely acknowledged as one of the most challenging procedures among plastic and reconstructive surgeons and is the most commonly revised facial plastic surgical procedure. Successful outcomes in rhinoplasty rely heavily on preoperative patient evaluation and counseling, understanding of nasal anatomy and wound healing, and precise surgical execution. It is important that the surgeon view rhinoplasty as not simply an aesthetic procedure but also one of nasal function. Nasal form has a profound impact on the perceived aesthetic of the facial skeleton; thus, the basic concepts of rhinoplasty are critical when evaluating dimensional alteration of facial form. The objective of this chapter is to review basic principles of rhinoplasty to optimize surgical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Patient evaluation

History

A thorough patient history provides essential information to understand the patient’s functional, aesthetic, and psychosocial goals. The patient’s medical history must be obtained to assess for comorbid conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and vascular insufficiency, which may impair wound healing. Medication history is also relevant and should be evaluated for medications that may affect coagulation. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications must be stopped at least 2 weeks before surgery. In addition, the surgeon must also inquire about the use of herbal medications that may have an anticoagulant effect (“Four G’s: ginseng, garlic, ginkgo balboa, and ginger). Previous history of nasal trauma, current or previous tobacco use, and illicit drug use (“cocaine nose”) must be elicited because these factors may affect the nasal structure and wound healing.

Surgical history is essential and is particularly relevant in the patient undergoing revision rhinoplasty. Should cartilage grafting be necessary, it is important to assess for availability of autologous septal, auricular, and rim cartilage and preoperatively counsel the patient on these potential grafting sites. In addition, the use of filler and alloplastic implants, such as L-shaped silicone implants and Gore-tex in the nose, is becoming increasingly common. Revision rhinoplasty patients with a history of alloplastic implants experience higher rates of infection, extrusion, and inconsistency in maintaining dorsal height and projection. , The surgeon should be prepared to remove such implants and perform autologous cartilage grafting, which can provide excellent long-term results. Furthermore, filler rhinoplasty carries the risk of ischemia and necrosis, which may require debridement and nasal reconstruction. We do not routinely advocate use of fillers or alloplastic implants in rhinoplasty due to the increased risk of adverse events.

The surgeon must also inquire about underlying cultural and psychosocial factors that may affect aesthetic goals. In the aging population, patients may seek a more youthful-appearing nose. Some patients may be seeking “Westernization” rhinoplasty. Finally, it is our routine practice to administer the Nasal Obstruction and Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) scale to each patient to objectively assess the presence and/or severity of nasal airway compromise. Failure to evaluate and address the patient’s nasal function will undoubtedly result in a poor surgical outcome.

Physical examination

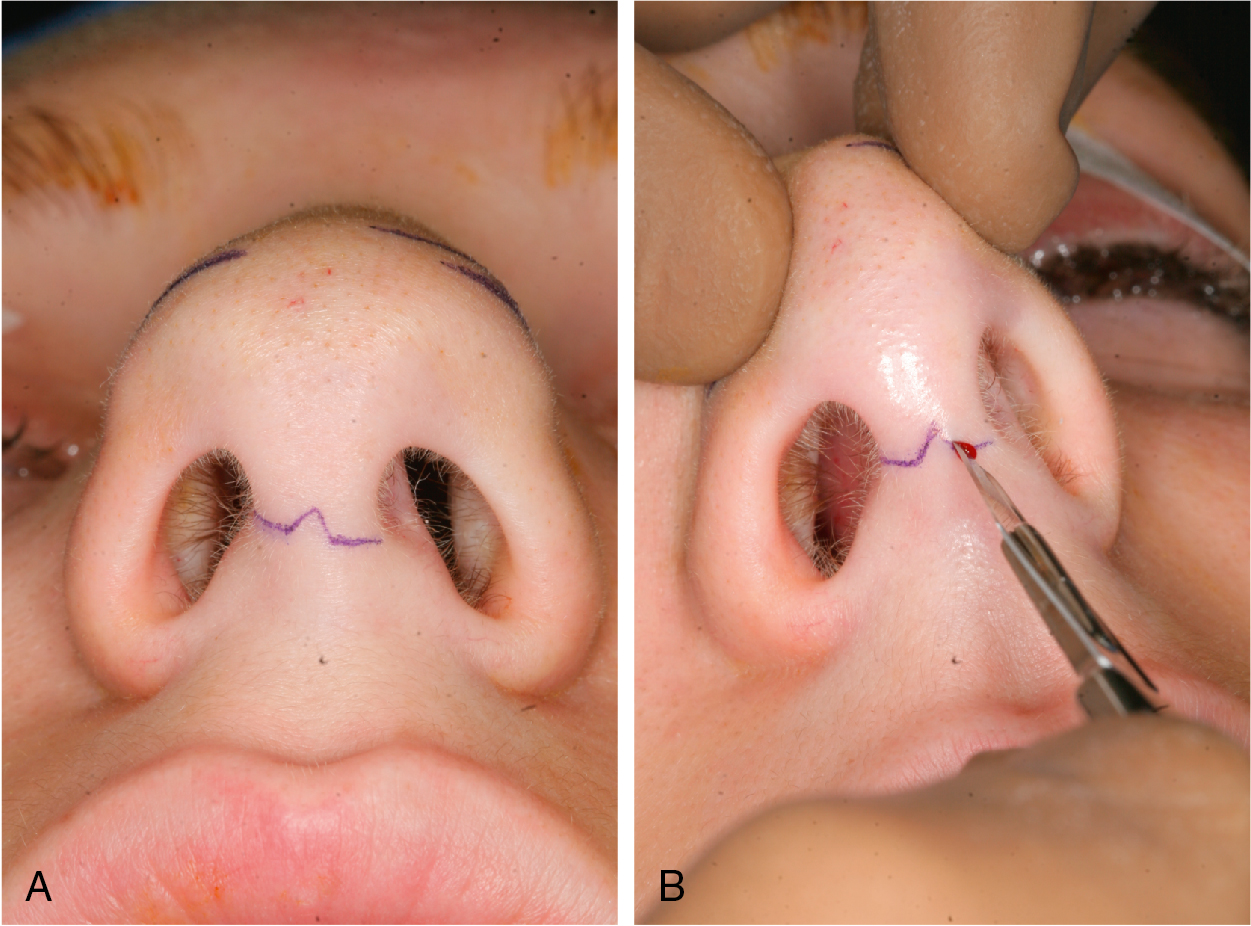

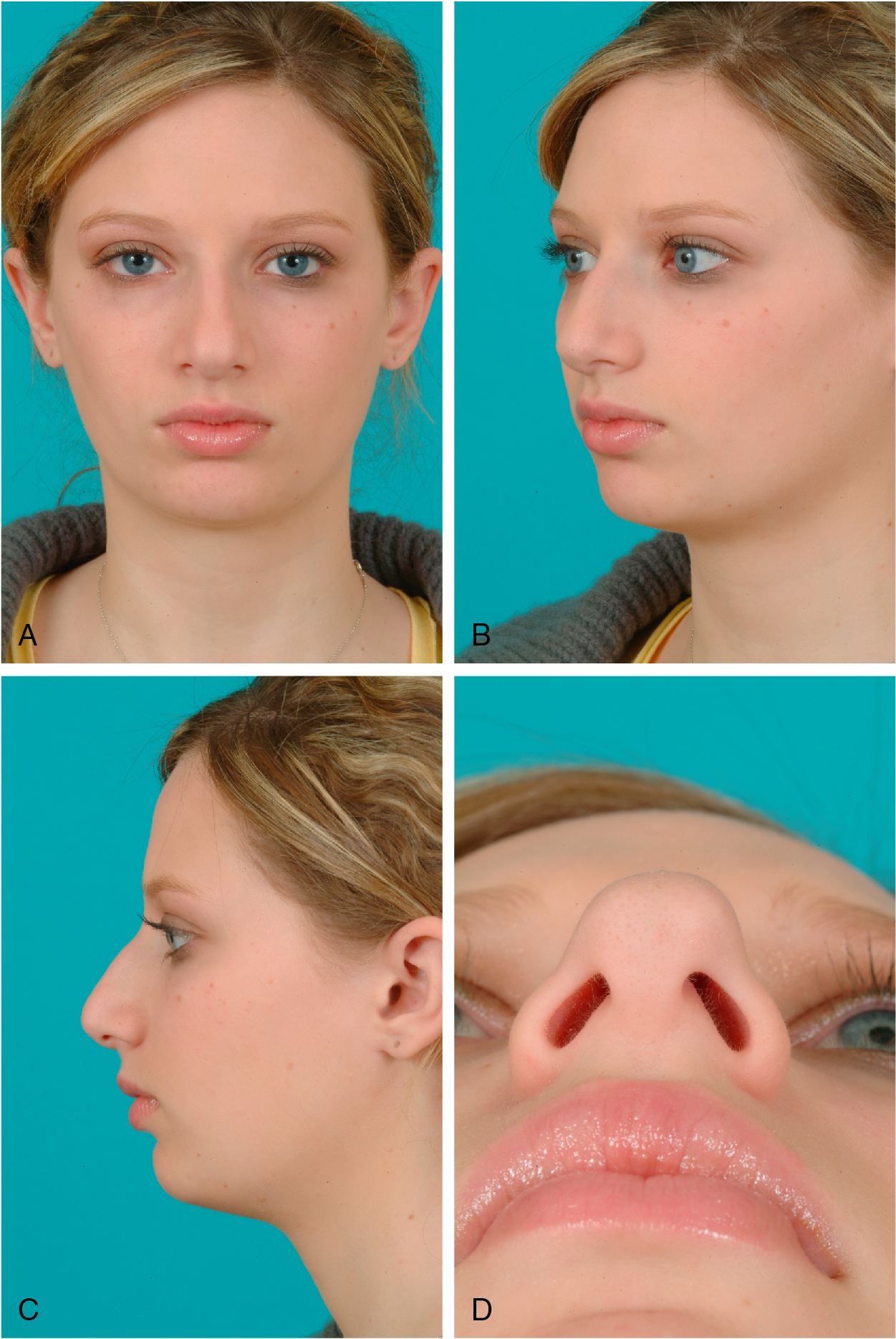

The cornerstone of physical examination in rhinoplasty is facial and nasal analysis. Preoperative photos and facial analysis are performed in frontal, three-quarter, lateral, and base views ( Fig. 29.1 A–D). The nose must be considered one of many aesthetic subunits of the face.

The quality of the patient’s skin is examined. Skin characteristics, such as thickness, sebaceous versus dry quality, and laxity, should be assessed. These factors may have a significant impact on healing, visibility of contour irregularities, and postoperative nasal tip and upper lip stiffness.

Next, palpation of the nasal bones is performed. Step-offs, asymmetries, and signs of previous surgery or trauma are noted. Palpation of the cartilaginous septum can provide information on the durability and support of the septal cartilage. The nasal tip is also palpated to assess the integrity of the lower lateral cartilages.

Intranasal examination is of paramount importance in all rhinoplasty patients. A nasal speculum is used to evaluate the septum, inferior turbinates, and external and internal nasal valves. Signs of septal perforation, turbinate hypertrophy, synechiae, and valve collapse should be noted and surgically addressed in functional rhinoplasty. A dynamic evaluation of the external nasal valve is performed. The patient is observed during inspiration for collapse of the lateral crura. A modified Cottle maneuver may also be performed. Improvement in nasal congestion with gentle traction of the lateral nasal wall may indicate poor internal nasal valve function. Endoscopic nasal examination is useful if the entire septum cannot be evaluated

Imaging or other preoperative diagnostic evaluations

Routine imaging or other diagnostic studies are not necessary in preoperative planning for rhinoplasty. If autologous rib cartilage is considered, computed tomography (CT) of the chest without contrast may be performed if there are concerns about calcification of the cartilage or if the patient has a history of chest surgery.

Indications/contraindications

Indications for rhinoplasty range from a variety of functional and/or aesthetic concerns. Examples of functional defects include saddle nose deformity, twisted nose deformity, nasal vestibular stenosis, cleft nose, nasal valve collapse, and traumatic nasal deformities. Patients with compromised nasal function must also undergo a comprehensive evaluation of aesthetic concerns to optimize outcomes. Other relative indications for rhinoplasty may include dorsal hump, alar malposition, alar flaring, nasal tip ptosis or bulbosity, widened nasal dorsum, aging face, and ethnic rhinoplasty. Revision rhinoplasty is seen frequently and may be pursued due to contour irregularities and symmetries, poor nasal function, pollybeak deformity, inverted-V deformity, and rocker deformity.

There are no strict contraindications to rhinoplasty because this surgery is elective. Patients with a history of multiple revisions and/or significant compromise of nasal function should be referred to an experienced revision rhinoplasty surgeon.

Preoperative planning

Thorough history and physical examination form the foundation of preoperative planning. A complete set of preoperative photos in frontal, oblique, and base views is obtained. We routinely use computer imaging to facilitate communication between the patient and the surgeon regarding the patient’s aesthetic goals ( Fig. 29.2 A, B). It is essential to remind the patient and document that these digitally reimaged photos serve as a guide to understanding the patient’s goals and are not a guarantee of postoperative results.

Primary operative approach

Selecting a surgical approach must take into consideration the operative goals and the surgeon’s experience. The external approach is preferred because it provides maximal exposure for complex nasal tip work or middle vault reconstruction. The surgeon should select the least invasive approach possible to avoid disruption of fibrous attachments contributing to nasal support.

Alternative approaches

If the patient requires conservative volume reduction of the lateral crura, shifting of the nasal bones, or dorsal hump reduction, an endonasal approach with marginal incisions may suffice.

Optimizing outcomes

Optimizing outcomes in rhinoplasty occurs in multiple states. Preoperative history and physical examination are essential to understanding functional issues of the nasal airway. Reviewing preoperative photos and computer imaging help elucidate the patient’s aesthetic goals. The surgeon must aim to create a nose that is in harmony with the patient’s overall facial appearance. The patient must be counseled that digital morphing of preoperative photos provides a template for surgical correction but does not guarantee the final surgical outcome. Preoperative counseling about potential risks and the course of wound healing and recovery is critical. The surgeon must also acknowledge the increased difficulty of revision rhinoplasty due to scarring and potentially decreased sources of cartilage grafting. Close and long-term postoperative follow-up are essential in the rhinoplasty patient because the patient may experience progressive postoperative changes years and decades after surgery. Through long-term follow-up of the patient, the surgeon may identify methods of refining the surgical technique to improve outcomes and produce lasting surgical results.

Surgical technique

External approach

The patient is positioned supine on the operating table, placed under general anesthesia, and orotracheally intubated. We routinely administer preoperative antibiotics (cefazolin). Local anesthesia is achieved with 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine infiltrated into the nasal tip, between the domes, and in the columella, marginal incision sites, lateral nasal walls, and submucoperichondrial plane along the nasal septum. We allow 10 to 15 minutes for the local anesthetic to obtain the maximal effect. A transcolumellar incision is then marked midway between the base of the nose and the top of the nostrils in an inverted-V ( Fig. 29.3 A, B). A No. 11 blade is used to make the transcolumellar incision with care to avoid damage to the caudal margin of the medial crura (see Fig. 29.3 A, B). Marginal incisions are then made along the caudal border of the lateral crura. A No. 15 blade is used to extend the columellar incisions laterally to meet the marginal incisions ( Fig. 29.4 ).