CHAPTER 37 Primary closed rhinoplasty

Physical evaluation

• Take a complete medical history.

• Evaluate entire face for shape, size, symmetry and proportion including the chin.

• Evaluate the nasal tip for size, shape, position of tip defining points and skin quality, especially thickness. Feel the nasal tip.

• Evaluate the nasal base and alae in relationship to the tip lobule and nasal pyramid.

• Evaluate the columella for position in the midline, straightness, width, length and position relative to alar rims.

• Observe the dorsal lines and the cartilaginous mid vault. Are the upper lateral cartilages providing midvault support. Do the internal valves collapse with inspiration?

• Evaluate the length of the nasal bones, width of the bony pyramid and the junction of the upper lateral cartilages and the nasal bones.

• Evaluate the profile for nasal length, height, contour, tip projection, radix depth and nasolabial angle.

• Evaluate the nose during facial animation (smiling from the front and profile) and observe changes in the alar base width, downward tip movement, and upper lip retraction.

• Careful examination of the septum, turbinates, internal and external valves.

• High quality photographs: front view, worms eye, three-quarter right and left views and profiles in repose and smiling.

Anatomy

Nasal tip

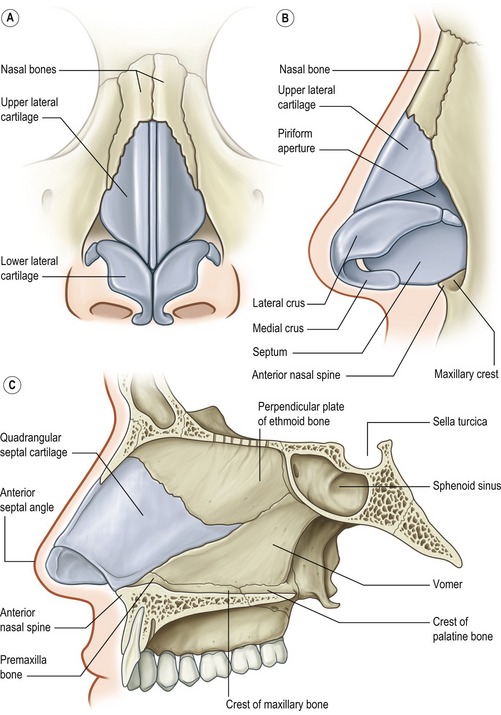

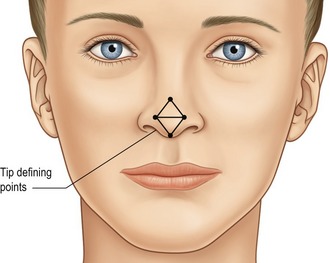

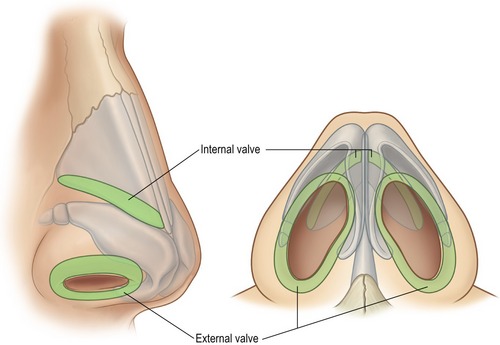

The nasal tip shape, size and projection is for the most part determined by the paired (though not necessarily symmetrical) alar cartilages, each of which have medial, middle and lateral crura, and their relationship to the adjacent structures (Fig. 37.1). The medial crura consists of flared (usually) footplates and the columella segment. The middle crus is a continuation of the medial crura and joins the lateral crus. The columella lobular junction is the transition from the nasal base to the tip lobule. The middle crus extends from the columella lobular junction to the lateral crus. The tip defining points, usually at the apex of the junction of the middle crus and lateral crus (the most projecting point on each side of the tip), produces an external light reflex (Fig. 37.2). The lateral crura make up the largest part of the nasal tip and join the accessory cartilages, which join the lateral crura to the pyriform aperture. The cartilages are supported by suspensory ligaments to each other and the caudal border of the upper lateral cartilages. The caudal edge of the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages, the nostril sills, the membraneous septum and the alae make up the external nasal valve (Fig. 37.3).

Upper lateral cartilages

The upper lateral cartilages and their attachment to the septum make up the cartilaginous mid-vault. The junction of the upper lateral cartilages with the cephalic margin of the lower lateral cartilages defines the scroll area. The angle of the junction of the septum and upper lateral cartilages at this point determine the internal valve (usually 10 to 15 degrees). The cephalic end of the upper lateral cartilages is overlapped by the nasal bones for several millimeters. This is important in maintaining mid-vault support. The junction of the upper lateral cartilages with the nasal bones and septum has a T-shaped contour and is known as the keystone area.

Nasal bones

The nasal bones vary in length and thickness and along with the ascending frontal process of the maxilla make up the bony vault. The nasal bones articulate with each other medially, the upper lateral cartilages inferiorly, the maxilla laterally, the frontal bones superiorly and the perpendicular plates of the ethmoid posteriorly. Nasal osteotomies (Fig. 37.4) are best performed through the thinner bone along the transition zone in the ascending frontal process of the maxilla that exists from the pyriform aperture to the radix.

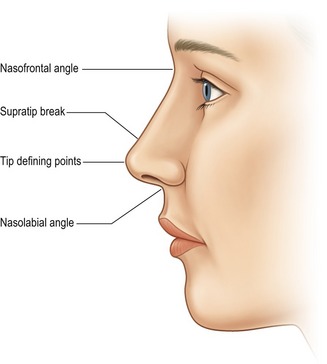

Nasal profile

The nasal profile (Fig. 37.5) is dictated by the osteocartilaginous vault and its relationship to the alar cartilages. Understanding this relationship is important when one considers reducing the dorsal hump (which is often more cartilage than bone). The amount of resection should be guided by the amount of tip projection, the nasal frontal angle and the supratip break on the lateral views. Tip projection is the distance the nose projects from the face, or more anatomically defined as the distance from the tip of the nose to the most posterior point of the nose-cheek junction. The nasal frontal angle, which approximates 115 to 130 degrees, its location and depth, will dictate if it should be left alone, lowered, augmented or if the dorsal hump should be reduced. Similarly, if the nose lacks tip projection, increasing tip projection (tip augmentation, strut graft) may alleviate the need for, or influence the amount of dorsal hump reduction.

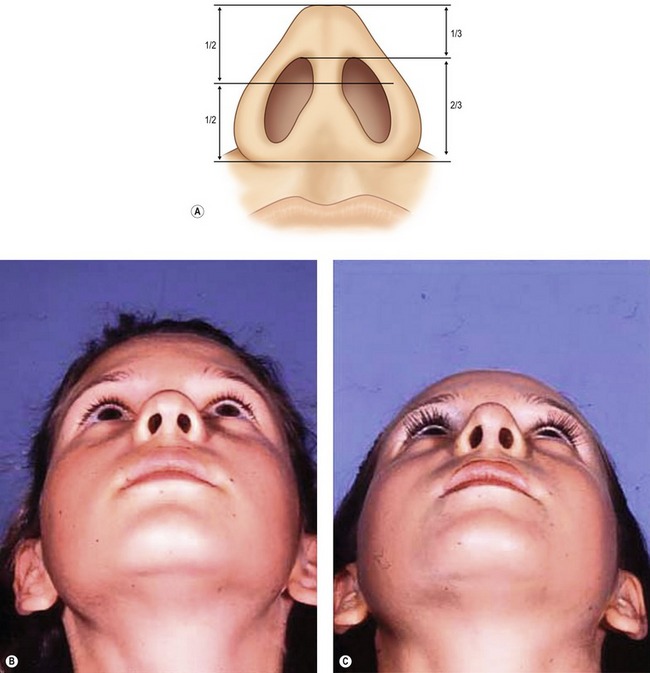

Columella and nasolabial angle

In the lateral view the preferred appearance of the columella is a slow curving structure traveling from the nasal tip to the base of the nose with a slight overhang in comparison to the alar base. In the basal view, a 2 : 1 ratio of the length of the columella to the length of the lobule is desirable (Fig. 37.6) and the base should be slightly wider than the confluence of the columella with the tip. In patients with a deficient columella, one will find a disruption of the length ratio between the columella and the lobule along with a distortion or the flaring of the alae. This is a common finding in some ethnic noses such as African and Asian. A retracted columella may occur in isolation or in combination with other abnormalities like a plunging tip. Even though the medial crura, the membraneous septum and the caudal septum all contribute to the shape of the columella, augmentation of the medial crura with a cartilage graft is the most common option for correction of a retracted columella. In comparison, an overhanging columella can often be corrected by a simple trim of the caudal septum or a reduction of the most caudal edge of the medial crura.

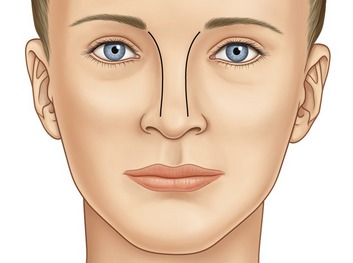

Nasal deviation

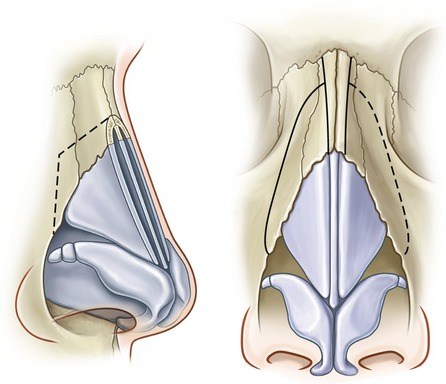

External deviation is primarily a result of deformities present in the nasal bones, cartilaginous septum or the nasal tip. A thorough pre-operative exam that evaluates the dorsal lines (Fig. 37.7) will help define the anatomic areas where the deviation occurs (upper, middle or lower third of the nose). The dorsal lines begin in the infra-brow area, curving gently, to converge at the level of the medial canthus, then diverge slightly at the keystone area and continue to diverge slightly as they continue down to the tip defining points. With this information the deviation can be addressed at different steps of the procedure: Infracture of asymmetric nasal bones for an upper third deviation, septoplasty and/or placement of unilateral spreader grafts for middle third deviations and revision of tip asymmetry or nasal spine repositioning for lower third deviation. Even in cases without deviations, the location of the nasal bones in reference to the nasal base width will dictate whether infracture is necessary. In most instances a wide nasal base, which is greater than 80% of the alar base width, will require infracture to improve the frontal view proportions.

Technical steps

A double-prong retractor placed along the alar rim lifts superiorly and the intercartilaginous grove is visualized (Fig. 37.8). Bilateral intercartilaginous incisions are made from medial to lateral keeping the back of the number 15 blade flush with the most caudal border of the upper lateral cartilages (Fig. 37.9). Care is taken not to retract too aggressively so as to place the incision in the mucosa on the edge or intranasal surface of the caudal end of the upper lateral cartilages, as scar contracture is likely to occur. The blade on each side is reversed and swept across the distal third of the nasal dorsum. Next, the soft tissue envelope covering the dorsum of the cartilaginous and bony framework is dissected in the subperichondral and subperiosteal planes with a Joseph periosteal elevator (Fig. 37.10). Dissection is limited to the dorsum so as to preserve the attachment of the soft tissue envelope to the lateral portions of the nasal bones. A transfixion incision is then performed with a curved button knife placed through each intercartilaginous incision and moved down against the caudal border of the septum (Fig. 37.11). The integrity of the membraneous septum and the columella is maintained by two skin hooks placed at the base of the columella and retracted caudally. Further inferior extension of the transfixion incision may be made with small curved Stevens scissors to permit access to the nasal spine and to the depressor septi nasi muscles.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree