Introduction

Pressure sores, also known as pressure injuries, pressure ulcers, decubitus ulcers, and bedsores, are a common problem. A pressure sore comprises a “localized injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear and/or friction.” The development of a pressure sore has significant implications for patients and healthcare providers, increasing length of admission and requiring increased utilization of healthcare resources. A US study published in 2019 estimated that hospital-acquired pressure injuries (HAPI) resulted in US$ 26.8 billion in additional healthcare costs annually, the majority due to treatment of higher grade (stage 3 or greater) injuries. With an aging population and rising prevalence of chronic conditions predisposing to pressure injuries, the incidence of pressure sores and their associated costs are likely to increase. This necessitates the development of specialist multidisciplinary teams for the care of patients with pressure injuries, including reconstructive surgeons for the management of advanced, complex, or refractory pressure sores.

Epidemiology

Pressure sore incidence and prevalence are determined by the characteristics of the population studied. Specific patient populations are particularly at risk of developing a pressure sore. The normal response to injury, such as the prolonged application of pressure, is withdrawal from the noxious source. However, in some individuals this does not occur, either because the pain stimulus is not present, as in sensory impairment, or because of an inability to reposition the body in order to redistribute pressure. Such patients include the elderly, the acutely unwell, patients who are immobilized as a result of spinal cord injury or following surgery, and patients with sensory impairment due to diabetes or chronic neurological conditions. Other risk factors include a past history of pressure sores, obesity, smoking, and peripheral vascular disease, among others ( Box 42.1 ).

- •

Past history of pressure sores

- •

Immobility (spinal cord injury, post-surgery/injury, critical illness)

- •

Neuropathy (spinal cord injury, diabetic neuropathy, other neurological causes)

- •

Abnormal posture (musculoskeletal abnormalities, spastic contractures)

- •

Anemia

- •

Poor nutrition

- •

Diabetes

- •

Peripheral vascular disease

- •

Obesity

- •

Poor skin quality (age, endocrine disorders)

- •

Smoking

The prevalence of pressure sores in the general population is low. An early study of the general population of a county in Denmark found a prevalence of 0.04%, and a study of elderly patients seen in general practice found a prevalence of 0.31–0.7%. However, the epidemiology of pressure sores among hospitalized patients is of greater interest, both due to the increased risk of pressure sores while admitted to a hospital or institution, and also because nosocomial pressure sore incidence is increasingly used as an indicator of healthcare quality and safety. A number of studies have examined the epidemiology of pressure sores among hospital inpatients, resulting in prevalence ranging from 10.2% to 19.7%, and incidence from 0 to 7.3%. Such wide variation partly results from differences in study design. However, there are two further major difficulties that prohibit study comparison.

The first is the variable nature of the population studied. As noted above, it has long been recognized that pressure sores are more common among certain patient populations, such as the elderly, among patients with spinal cord injuries, and among patients with sensory impairment. As such, the prevalence of pressure sores in a given hospital or institution more likely represents the patient population serviced by that facility than any difference in quality of care or pressure injury prevention strategies. As an example, a centre which specialises in the care of patients with spinal cord injuries is likely to have a much higher incidence of pressure sores than other institutions which many be identical in every other regard. The second difficulty is how the study defines a pressure sore. Though most studies now use the International classification system (see Table 42.1 ), they may differ on whether or not the milder forms are included, and frequently exclude grade 1 pressure injury which comprises only non-blanching erythema (see below, under Patient Assessment). The EPUAP collected detailed data in 2001 and 2002 and found an overall prevalence of pressure sores in five European hospitals of 18.1%. However, the majority of these consisted of only a grade 1 pressure injury, with a minority (2.5% of the total) suffering the most severe, a grade 4 pressure injury. For these reasons it is important to carefully review the methodology when interpreting a given study of the epidemiology of pressure sores, and it should be interpreted warily if used as an indicator of healthcare quality and safety.

| Stage | Features |

|---|---|

| Stage I | Non-blanching erythema of intact skin. Area may also be painful, firm, soft, warmer, or cooler by comparison to adjacent tissue |

| Stage II | Partial-thickness skin loss involving epidermis and/or dermis presenting as a shallow open ulcer with a pink wound bed without slough/eschar. May also present as open/ruptured fluid-filled blister |

| Stage III | Full-thickness skin loss with subcutaneous fat visible but without exposure of deeper structures such as bone, tendon, or muscle |

| Stage IV | Full-thickness tissue loss with extensive tissue necrosis and exposure and/or involvement of deeper structures such as bone, tendon, or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present |

| Suspected deep tissue injury | Area of discolored intact skin or blood-filled blister. Skin integrity maintained with suspected damage to deeper tissues |

| Unstageable | Full-thickness tissue loss in which actual depth of ulcer is obscured by slough and/or eschar in the wound bed |

Pathophysiology

Pathologically, pressure sores are areas of localized tissue necrosis resulting from external forces. As the name suggests, external pressure is the key causative element in their pathogenesis. In experimental studies of the effect of pressure on limb vascular volume using human volunteers in the 1940s, Landis established a threshold pressure of 35 mmHg, noting that external pressures above this figure resulted in reduced vascular volume, likely reflecting capillary occlusion. This process, if repeated or sustained, ultimately results in ischemic necrosis of skin, subcutaneous tissue, and deeper tissues. Further studies by Kosiak demonstrated irreversible changes in muscle of rats subjected to 70 mmHg of constant pressure for a period of 2 hours or more. Such changes were also seen in rats exposed to pressure which was applied and removed at 5-minute intervals, but only at much higher pressures (155 mmHg). Importantly, it was also established that denervated muscle required the same magnitude and duration of pressure in order to demonstrate signs of injury and that normal and denervated muscle had the same susceptibility to pressure injury. This was contrary to prior thinking which supposed that the absence of neurotrophic factors secreted by functional nerves was causative in pressure sore pathogenesis.

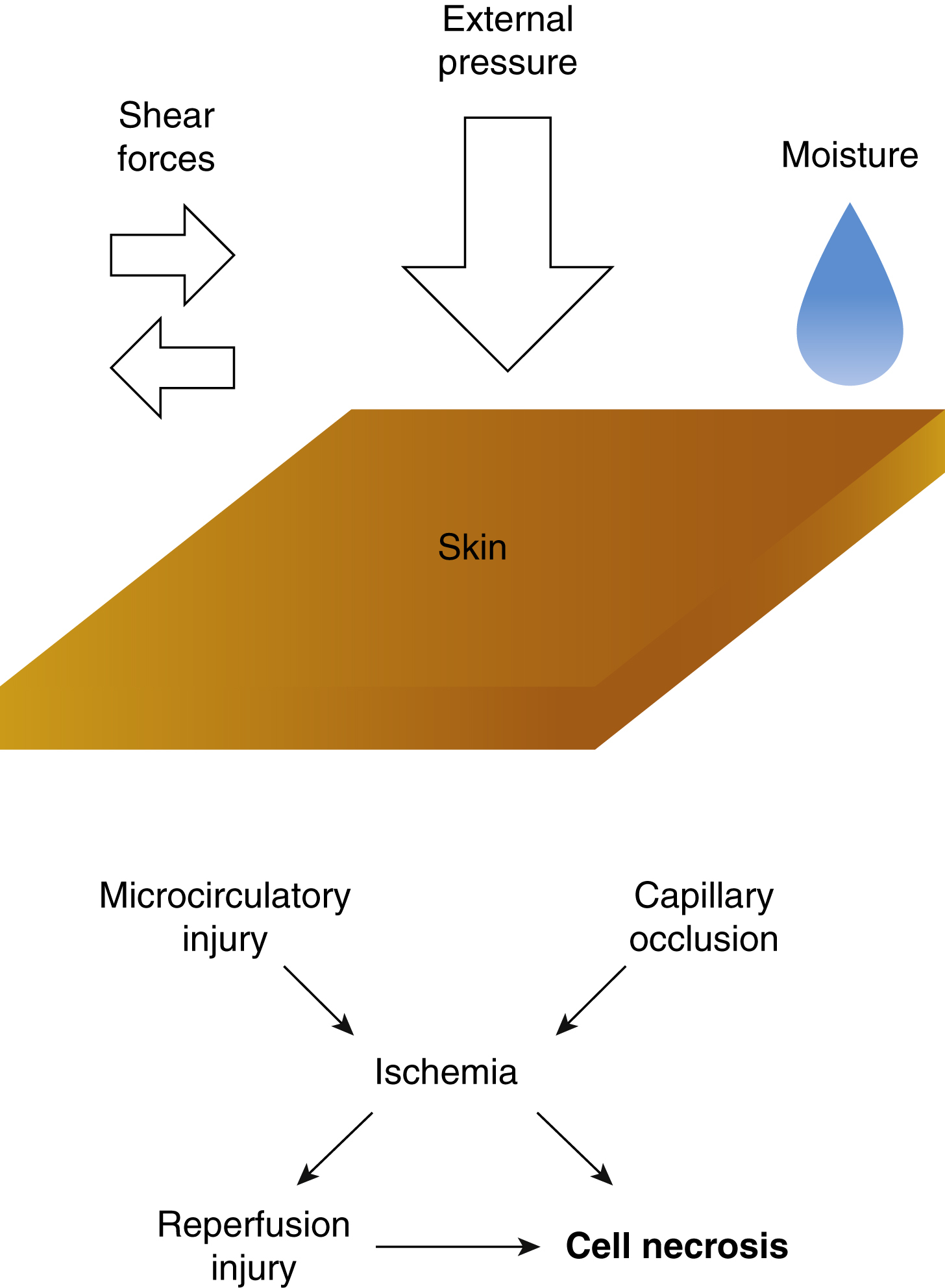

Studies in animal models have demonstrated pressure sore formation and progression resulting from repeated and sustained application of pressure, the extent of injury varying according to these two factors. In combination with external pressure, shear stress and the presence of moisture may contribute to the extent of injury. Shear stress is a mechanical force acting in parallel to the surface under compressive pressure. In the presence of a significant degree of shear stress, the magnitude of external pressure required to cause a pressure injury is significantly reduced. This is hypothesized to occur due to the deforming effect of shear stress on tissues deep to the skin resulting in direct injury through sustained deformation of cells and worsening of ischemia by microcirculatory injury. Recent research has also identified reperfusion injury as an important factor in the pathogenesis of pressure sores, with greater tissue necrosis and reduction in functional capillary density following repeated compression and release of tissues by comparison with compression alone. The interaction of these biomechanical factors in the pathogenesis of a pressure sore is complex, and research into their relative contributions is ongoing. However, it is clear that the key pathological insult in the formation of a pressure sore is repeated compression of tissues by external pressure over a prolonged period, which may be exacerbated by contributory factors including shear forces, moisture, and reperfusion injury ( Fig. 42.1 ).

Pressure sores have been described as occurring in many locations, though the vast majority occur over bony prominences in the lower limb. The aforementioned EPUAP study found the following to be the commonest sites of pressure injury of any severity, in descending order (percentages stated according to data collected in the United Kingdom): sacrum (37.5%), heel (26.2%), ischium (13.7%), elbow (10.3%), ankle (6.4%), and hip (5.8%). The reason for pressure injuries occurring most frequently over bony prominences may seem intuitively obvious, nevertheless the physiological explanation follows. Sangeorzan et al compared the effects of applied external pressure to skin overlying the subcutaneous surface of the tibia with that over tibialis anterior. The researchers established that much greater external pressure was required to reduce capillary perfusion in skin over muscle than in skin over bone. Crucial to this is the realization that the subcutaneous (interstitial) tissue pressure is of much greater significance than the external pressure, and the interstitial pressure resulting from a given external pressure is determined by the nature of those tissues and whether they overlie bone. As such, over bony prominences where there is a thinner layer of soft tissue between skin and bone, a relatively minor external pressure may result in significant, ischemia-inducing interstitial pressure.

Prevention

Effective pressure sore prevention requires ongoing assessment of patients for risk factors together with appropriate interventions to minimize risk to vulnerable patients. Pressure sore risk factors are common in the hospitalized population (see Epidemiology, above).

Assessment of Risk

Pressure sore risk assessment should be performed for all patients on admission and repeated regularly in order to identify at-risk patients and track response to interventions. A number of structured risk assessment tools have been developed to identify patients at risk of developing a pressure sore. The Norton scale was developed in 1962, from which were developed the Waterlow and Braden scales in 1985 and 1987, respectively. The latter two are in widespread use today and have been demonstrated to have a high sensitivity in predicting patients likely to develop a pressure sore. There is, however, no good-quality evidence to suggest that the use of these tools results in a decreased incidence of pressure sores. Regardless of whether or not a scale is used, assessment of patients for pressure sore risk allows identification of patients likely to benefit from prevention strategies.

Prevention Strategies

Interventions for the prevention of pressure sores are of two general types. First, the extrinsic causes of pressure sores (see Pathophysiology, above) should be minimized. The effect of external pressure may be ameliorated using pressure redistribution strategies, such as manual repositioning and the use of appropriate lifting devices for patient transfers. There is no good evidence to recommend any particular manual positioning regimen over any other. Use of pressure-relieving support surfaces such as gel-filled overlays during surgery and air mattresses or cushions on the ward are also beneficial, though again there is nothing to suggest the superiority of any particular surface type, except over basic mattresses. , Medical-grade sheepskins are also of benefit in reducing pressure sore risk, which may be particularly relevant in the nursing home environment.

However, if achievable, early mobilization is the best strategy for external pressure reduction. Daily skin care, including moisturization of dry skin in areas prone to pressure sore development, and prompt cleaning and changing following episodes of incontinence reduces the effect of moisture and may allow the identification of early stage pressure injuries. Secondly, modifiable risk factors should be managed. The management of any medical comorbidities should be reviewed and the patient’s nutritional state assessed and managed if necessary. Patients should be discouraged from smoking, and obese patients should be counseled regarding the benefits of weight reduction. These strategies are summarized in the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI)’s recommendations for pressure sore prevention ( Box 42.2 ).

- 1.

Conduct a pressure sore admission assessment for all patients

- 2.

Reassess risk for all patients daily

- 3.

Inspect skin daily

- 4.

Manage moisture

- 5.

Optimize nutrition and hydration

- 6.

Minimize pressure

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree