Premalignant and Malignant Skin Neoplasms

Solar keratosis

Solar keratosis

Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma

Bowen’s disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ)

Squamous cell carcinoma of mucous membranes

Keratoacanthoma

Keratoacanthoma

Basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma

Superficial basal cell carcinoma

Morpheaform basal cell carcinoma

Melanoma

Melanoma

Superficial spreading melanoma

Nodular melanoma

Lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma

Acral lentiginous melanoma

Paget’s disease of the breast and extramammary Paget’s disease

Paget’s disease of the breast and extramammary Paget’s disease

Overview

This chapter is intended to help health care providers distinguish skin cancers from precancers and benign growths. The ability to make clinical diagnoses, to identify benign versus malignant lesions, especially in their less classic presentations, is an important skill that comes with focused, repetitive visual scrutiny.

By far, the most important skin lesion for the health care provider to recognize is melanoma.

The therapy of malignant lesions should be undertaken only by persons experienced in skin cancer therapy.

Solar Keratosis

Basics

An aging population that is living longer, in an atmosphere with a declining ozone layer and with more outdoor and leisure time to bask in this ultraviolet environment, has led to a dramatic increase in sun-related skin damage (dermatoheliosis) and precursors to skin cancer such as solar keratoses. It is estimated that 60% of predisposed people older than 40 years have at least one solar keratosis, and many of them have new solar keratoses each year.

Solar keratosis, also commonly known as actinic keratosis, is the most common sun-related skin growth. Whether this lesion is benign (premalignant) or malignant (squamous cell carcinoma in situ) from its onset is controversial. What is accepted, however, is that solar keratoses have the potential to develop into invasive squamous cell carcinomas.

Solar keratoses are more common in men, particularly those who work, or have worked, in outdoor occupations, such as farmers, sailors, and gardeners, and those who participate in outdoor sports. The incidence of solar keratosis, as with all of the skin cancers described in this chapter, is highest in Australia and in the Sun Belt of the United States.

It is estimated that 1 in 20 lesions eventually becomes squamous cell carcinoma. It is also accepted that the invasive carcinomas that develop from these actinic keratoses are of a very slow-growing, indolent, unaggressive type, and the prognosis usually is excellent. Distant metastases are extremely rare. Consequently, among dermatologists, there is an ongoing debate regarding the need to be aggressive or laissez-faire in the approach to these lesions.

Pathogenesis

The development of solar keratoses, which is directly proportional to sun exposure, is seen in people who are fair-skinned, burn easily, and tan poorly.

These lesions are rare in dark-skinned persons.

Histopathology

Cellular atypia is present, and the keratinocytes vary in size and shape. Mitotic figures are common.

The histologic changes of individual cells are indistinguishable from those seen in squamous cell carcinomas.

Description of Lesions

Lesions usually appear as multiple discrete, flat or elevated, verrucous, scaly lesions. Their texture typically feels rough to the touch (Fig. 22.1).

They typically have an erythematous base covered by a white, yellowish, or brown scale (hyperkeratosis) (Fig. 22.2).

Lesions are usually 3 to 10 mm in size and can gradually enlarge, thicken, and become more elevated and thus develop into a hypertrophic solar keratosis (Figs. 22.3 and 22.4) or a cutaneous horn (Figs. 22.5 and 22.6).

22.2 Solar keratoses. Thicker, tan-colored, hyperkeratinized lesions are more obvious in this patient.

22.3 Solar keratoses, hypertrophic. The solar keratoses occur primarily in areas of sun-exposed skin in this elderly woman.

22.4 Solar keratosis. The pinna of the ear is a very common site for these lesions in men. (Note the similarity to Fig. 21.33, an illustration of chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis.)

22.5 Solar keratosis. This large cutaneous horn was produced by an underlying hypertrophic solar keratosis.

22.6 Solar keratosis. This cutaneous horn was also produced by an underlying solar keratosis. A biopsy was performed to rule out squamous cell carcinoma.

A cutaneous horn is a hornlike projection of keratin. In addition to solar keratoses, warts and squamous cell carcinomas in situ (Bowen’s disease) may also produce a cutaneous horn on their surface.

Sometimes, solar keratoses are tan or dark brown (pigmented solar keratosis) (Fig. 22.7) and are often clinically indistinguishable from a solar lentigo (see Fig. 21.4)

In time, a solar keratosis may develop into a squamous cell carcinoma.

Distribution of Lesions

Solar keratoses are most often seen on a background of sun-damaged skin.

They are found chiefly on sun-exposed areas: the face, especially on the nose, temples, and forehead.

They are also commonly noted on the bald areas of the scalp and the tops of the ears in men, the dorsa of the forearms (Fig. 22.8) and the dorsa of the hands, the “V” of the neck, and the neck below the occipital hairline and below the ears.

The vermilion border of the upper lip is another very common site for solar keratoses (Fig. 22.9).

22.10 Actinic cheilitis. This patient is undergoing treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil for multiple solar keratoses of his lower lip.

They may also occur on any area that is chronically or repeatedly exposed to the sun, such as the legs in women.

Extensive involvement of the mucous membranes of the lower lips (generally the lower lip) is known as actinic cheilitis (Fig. 22.10).

Clinical Manifestations

Solar keratoses are usually asymptomatic, but they may itch and become tender or irritated. Patients often report one or several “dry” scaly bumps on sun-exposed areas that do not respond to moisturizers.

They are of cosmetic concern to many patients.

They may regress spontaneously.

Diagnosis

Clinically, very small lesions are often better felt than seen. Palpation of these scaly growths reveals a gritty, sandpaperlike texture.

A shave biopsy is performed if the diagnosis is in doubt.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

See later discussion.

Solar keratosis may be indistinguishable from a squamous cell carcinoma.

Untreated, squamous cell carcinoma becomes indurated, with a tendency to ooze, ulcerate, or bleed.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

See later discussion.

Classically, this lesion is a pearly, shiny papule with telangiectasias.

It may be indistinguishable from solar keratosis, particularly when it is small, ulcerated, manipulated, or pigmented.

Verruca Vulgaris (Wart)

Warts may also be indistinguishable from solar keratoses.

Seborrheic Keratosis

See also Chapter 21, “Benign Skin Neoplasms.”

A seborrheic keratosis may, at times, be indistinguishable from a solar keratosis.

Seborrheic keratosis has a “stuck-on” appearance and may occur in areas not exposed to the sun.

Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Helicis

See also Chapter 21, “Benign Skin Neoplasms.”

These lesions, when present on the helices or antihelices of the ears, may be easily confused with solar keratoses.

Prevention begins with educating the patient to limit sun exposure by using sunscreens and wearing protective clothing.

Treatment is achieved by destruction of solar keratoses (see Chapter 26, “Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures”).

Destructive Methods

Liquid nitrogen (LN2) is the mainstay of treatment for solar keratoses. LN2 is most useful when lesions are few in number. It is applied to individual lesions for 3 to 5 seconds.

For thick, hyperkeratotic lesions, biopsy followed by electrocautery or electrocautery alone is performed.

Chemotherapy

Topical application of Efudex, a 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) cream, is a method that may be used when lesions are too numerous to treat individually. 5-FU interferes with the synthesis of DNA; it destroys dysplastic cells and spares normal cells. Enough medication is applied to cover the entire area with a thin film. This is done twice daily for 2 to 4 weeks for facial lesions. Other body sites require longer treatment (e.g., 6 to 8 weeks for the arms).

Alternatively, a 0.5% 5-FU cream (Carac) may be applied only once daily. This preparation is reportedly less irritating than the stronger 5% 5-FU agents.

During this treatment, the lesions become increasingly red and crusted, and subclinical lesions become visible. This situation can result in a very red, disfiguring complexion; however, if the patient completes the treatment, the lesions usually heal within 2 weeks of stopping treatment, the skin becomes smooth, and the majority of the solar keratoses are gone (Figs. 22.11 A and B).

Immunotherapy

Imiquimod (Aldara) 10% cream is a local inducer of interferon. It is applied twice weekly to involved skin for 16 weeks until a response similar to that described with 5-FU agents is elicited.

Other Treatments

Topical tretinoin (Retin-A) has been shown to reverse mild actinic damage to the skin.

Photodynamic therapy can also be used to treat multiple actinic keratoses. In this treatment, topical 5-aminolevulinic acid accumulates preferentially in the dysplastic cells. On exposure to irradiation with light of the appropriate wavelength, oxygen-derived free radicals are generated, and cell death results.

Chemical peels and dermabrasion are also used in patients with numerous facial solar keratoses.

Diclofenac sodium 3% (Solarase) gel is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory preparation that has been introduced as a topical treatment for solar keratoses. This agent appears to be less irritating than the standard 5-FU products and Aldara; however, its efficacy does not match theirs.

Because solar keratoses are more often easily felt than seen, the clinician should run ungloved fingers over the patient’s skin to detect all lesions.

The number of solar keratoses is directly related to cumulative sun exposure. Childhood exposure or sun damage is “accumulated like interest on money in the bank”; some of this damage seems to be reversed and prevented by sun avoidance and sun protective measures.

Sunscreens should also be applied to the lower lip to prevent actinic cheilitis.

Topical 5-FU treatment can be likened to using a “smart bomb” in which the “bomb” (in this case 5-FU) targets only the “enemy” (the rapidly growing dysplastic cells).

Imiquimod (Aldara) cream may “immunize” patients against their own dysplastic keratinocytes; in fact, some dermatologic surgeons use it prophylactically to prevent recurrence. Aldara is applied two times per week for a full 16 weeks.

If a lesion persists or recurs, despite treatment, it should be examined by biopsy.

The decision to treat solar keratoses can be based on cosmetic reasons, symptom relief, or, most important, the prevention of malignancy.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Basics

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a malignant epithelial tumor arising from keratinocytes of the epidermis.

It is the second most common type of skin cancer. SCC is diagnosed much less frequently than basal cell carcinoma (BCC), but it carries a risk of metastasis. It occurs in an older age group than does BCC.

Although it is very rare in dark-skinned persons, SCC can be more aggressive in these individuals.

The majority of SCCs arise in solar keratoses (see earlier discussion). Such SCCs that develop from solar keratoses are slow growing, minimally invasive, and unaggressive, and the prognosis is usually excellent because distant metastases are extremely rare.

An SCC may appear de novo without a preceding solar keratosis.

When a metastasis from a cutaneous SCC (non–mucous membrane) does occur, it is more likely to result from lesions that appear on the ears or on the vermilion border of the lips, from lesions that are poorly differentiated, from recurrent lesions, or from tumors larger than 2 cm in diameter.

Also apt to be more aggressive are SCCs that may occur from causes other than sun exposure. For example, a SCC may arise in long-standing scars or from sites previously exposed to ionizing radiation and long-term exposure to psoralen and ultraviolet A light (PUVA) (see Chapter 3, “Psoriasis”). A SCC may also emerge from pre-existing human papilloma virus infection (verrucous carcinoma), in the skin of organ transplant recipients, or chronic inflammatory lesions (e.g., cutaneous lupus erythematosus), as well as cutaneous ulcers (e.g., venous stasis ulcers) or other nonhealing wounds.

As with solar keratosis and BCCs (see later discussion), SCC is related to sun exposure and is noted more frequently in those with a greater degree of outdoor activity.

Histopathology

In the in situ type of SCC (Bowen’s disease), only the full thickness of the epidermis is involved. The basement membrane remains intact. Atypical keratinocytes (squamous cells) show a loss of polarity and an increased mitotic rate.

An invasive SCC penetrates into the dermis. It has various levels of anaplasia and may manifest relatively few to multiple mitoses and may display varying degrees of differentiation such as keratinization.

Risk of Metastasis

The risk of metastasis of SCC depends on its degree of differentiation, depth of penetration, and location.

SCC occurs in several clinical variants that vary in their aggressiveness.

In situ SCC (Bowen’s disease) has a low incidence of metastasis.

An SCC arising in a solar keratosis also has a low incidence of metastasis.

Lesions on mucous membranes have the highest risk of metastasis.

Tumors that are induced by ionizing radiation or those that arise in old burn scars or in inflammatory lesions also are also more likely to metastasize.

22.13 Squamous cell carcinoma. This hyperkeratotic nodule arose in an immunocompromised patient in a site previously exposed to ionizing radiation. |

Description of Lesions

Lesions appear as papules, plaques, or nodules (Fig. 22.12) that grow slowly.

Lesions are scaly or ulcerated.

Lesions may have a smooth or thick hyperkeratotic surface (Fig. 22.13).

As with solar keratoses, an SCC may also produce a cutaneous horn on its surface.

An SCC may appear as a reddish brown nodule. It may, at times, be indistinguishable from a hypertrophic solar keratosis or a BCC.

Tumors may ulcerate when they are neglected (Fig. 22.14).

Distribution of Lesions

Lesions occur in the same locations as do solar keratoses: sun-exposed areas such as the face, the dorsa of the forearms and hands, and the “V” of the neck.

In men, SCCs tend to arise on the bald areas of the scalp and on the tops of the ears as well as the posterior neck below the occipital hairline.

In women, lesions tend to occur on the legs as well as other relatively sun-exposed locations.

In individuals of African origin there is an equal frequency in sun-exposed and unexposed areas.

Clinical Manifestations

Most SCCs are asymptomatic, although bleeding, pain, and tenderness may be noted.

Slow-growing, firm papules with the ability to produce scale (keratinization) tend to be more clearly differentiated and less likely to metastasize.

Softer, nonkeratinizing lesions are less well differentiated and are more likely to spread (Fig. 22.15).

Clinical Variants

Intraepithelial Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Bowen’s disease (SCC in situ) and erythroplasia of Queyrat are intraepithelial SCCs that often arise in sites that are not exposed to the sun such as the trunk or extremities. When an SCC in situ lesion occurs on the penis, it is referred to as erythroplasia of Queyrat (Fig. 22.16).

Bowen’s disease (Fig. 22.17) is one of the few skin cancers that should be considered as a diagnosis in African-American, Afro-Caribbean, and African blacks. This non–sun-related skin cancer tends to arise on the extremities de novo (Fig. 22.18).

22.16 Erythroplasia of Queyrat. This subtle, nonhealing, shiny erosion on the perimeatal area of the glans penis proved to be an SCC in situ. (Courtesy of Joseph S. Eastern, M.D.)

22.17 Bowen’s disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ). These lesions closely resemble scaly psoriatic or eczematous plaques.

22.18 Bowen’s disease in an African-American woman. This plaque arose de novo in a non–sun-exposed location.

22.19 Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a burn scar. The likelihood of metastasis of this lesion is significant.

If a frank SCC occurs in an old scar (Fig. 22.19) or in a lesion of discoid lupus erythematosus, the lesion should be treated aggressively.

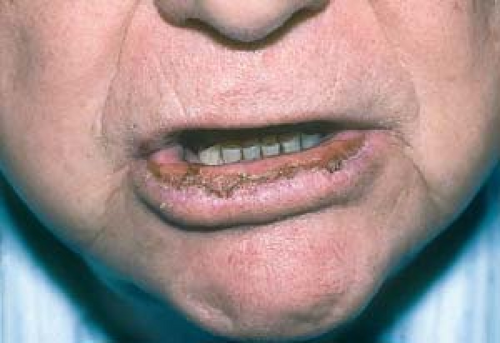

Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Mucous Membranes

This condition (Fig. 22.20) may present as leukoplakia, nonhealing fissures, or ulcerations. Such lesions have significant metastatic potential.

Treatment is beyond the scope of this publication.

Solar Keratosis (Actinic Keratosis)

This lesion is often indistinguishable from SCC (see earlier discussion).

Basal Cell Carcinoma

See later discussion of BCC.

BCCs are generally pearly and telangiectatic.

They appear at a younger age than do SCCs.

BCC may be indistinguishable from SCC, particularly if the lesion is ulcerated.

Keratoacanthoma

See later discussion.

This lesion also may be clinically and, at times, histopathologically, indistinguishable from a SCC.

It is fast growing.

Usually, it has a typical central crater.

Melanoma

See later discussion.

An amelanotic melanoma (lacking typical pigmentation) or an ulcerated melanoma may also be impossible to distinguish from a SCC.

Psoriasis/Eczema

Seborrheic Keratosis

This extremely common benign skin growth becomes apparent after 40 years of age (see Chapter 21, “Benign Skin Neoplasms”).