Pigmentary Disorders

Disorders of hypopigmentation

Disorders of hypopigmentation

Vitiligo vulgaris

Other forms of hypopigmentation

Postinflammatory hypopigmentation

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis

Other types of hypomelanosis

Disorders of hyperpigmentation

Disorders of hyperpigmentation

Melasma

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation

Phyto-photodermatitis and berloque dermatitis

Poikiloderma of Civatte

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud disease)

Acanthosis nigricans

Carotinemia

Overview

Skin color is mainly due to melanin. The amount of melanin is determined primarily by hereditary factors and by the result of exposure to ultraviolet radiation (tanning).

Melanogenesis

Melanocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis produce melanin. The melanin pigment is manufactured on melanosomes (intracytoplasmic organelles). Once made, the melanosomes are carried along dendrites and delivered to neighboring keratinocytes of the epidermis.

Darkly pigmented skin has melanosomes that contain more melanin and are larger in diameter than in light skinned individuals, and when those melanosomes are transferred to keratinocytes, they are singly dispersed and degrade more slowly.

Increase in melanin (hyperpigmentation or hypermelanosis) can be due to an increased number melanocytes or from increased production of melanin. Reduction in melanin production or a loss of melanocytes results in pale patches (hypopigmentation or hypomelanosis) or white patches (leukoderma). Vitiligo is a specific type of leukoderma characterized by depigmentation of the epidermis due to a partial or complete loss of melanocytes.

Disorders of Hypopigmentation

Vitiligo Vulgaris

Basics

An acquired disorder of skin depigmentation, vitiligo vulgaris (common vitiligo) affects 1% to 2% of the world’s population.

Thirty percent of patients with vitiligo report a positive family history of the disorder.

A distinct form of vitiligo occurs in children, and this form is often segmental or dermatomal in its distribution. Some children may develop halo nevi, which are melanocytic nevi encircled by a white halo of depigmentation (see Chapter 21, “Benign Skin Neoplasms”).

Pathogenesis

Although the cause of vitiligo vulgaris is still unknown, the condition is thought to result from an autoimmune process that prompts the loss of melanocytes. Vitiligo may develop in patients with other diseases that are believed to have an autoimmune basis (e.g., thyroid dysfunction, Addison’s disease, alopecia areata, diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia), and this finding supports the hypothesis that an immune mechanism may be involved in its pathogenesis.

Another theory proposes that vitiligo is caused by an abnormality of nerve endings adjacent to skin pigment cells.

Description of Lesions

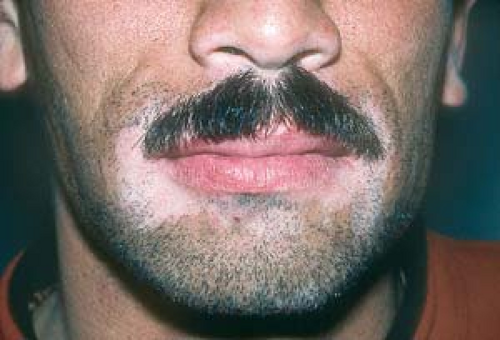

Physical examination of a patient with vitiligo reveals hypopigmented (Fig. 14.1) or depigmented, chalk-white macules.

Occasionally, the lesions may have various shades of color and may include islands of repigmentation (Fig. 14.2).

In dark-skinned people, pigmentary loss may be observed at any time of year, whereas in light-skinned people, the lesions may be most obvious in the summer, because the tanning effects of the summer sun can accentuate the contrast between the light and dark skin.

14.1 Vitiligo. Depigmented macules are characteristic of vitiligo vulgaris. Note the characteristic periorificial distribution in this patient. |

Distribution of Lesions

Vitiliginous lesions tend to have a bilateral, symmetric distribution.

They frequently occur on acral areas (e.g., the hands and feet), body folds, bony prominences, and external genitals.

Lesions characteristically appear around orifices (e.g., the mouth, eyes, nose, and anus), but they may also involve the eyebrows, eyelashes, and scalp hair, resulting in white hairs (leukotrichia).

In severe cases, vitiligo may be more widespread (Fig. 14.3) or even total (vitiligo universalis).

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations often develop cyclically. A rapid loss of pigment is followed by a stable period (during which some repigmentation may occur), and then generally by recurrence.

Some patients spontaneously experience partial repigmentation; total repigmentation is unusual.

Patients with severe vitiligo may experience embarrassment and lowered self-esteem.

Diagnosis

A clinical diagnosis of vitiligo is usually based on the characteristic appearance of the skin lesions.

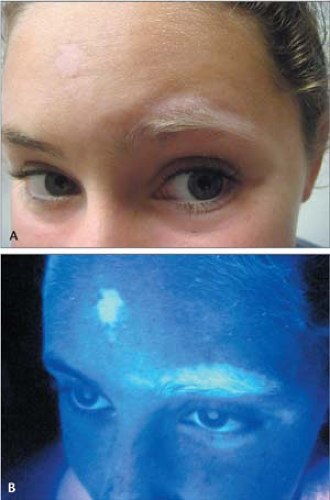

The diagnosis can be aided by Wood’s lamp examination; this should reveal a milk-white fluorescence. Wood’s lamp is a handheld black light that makes hypopigmented areas appear lighter and depigmented areas (e.g., those produced by vitiligo) appear as a pure white or bluish white fluorescence (Fig. 14.4).

14.4 A and B Vitiligo. Wood’s lamp examination reveals a “milk-white” fluorescence in areas depigmented by vitiligo. Note the depigmented eyebrows and eyelashes. |

Postinflammatory Hypopigmentation

See also later discussion.

Because the lesions of this disorder are not totally depigmented, they are generally off-white in color.

Often, patients who have postinflammatory hypopigmentation reveal a history of preexisting inflammatory dermatitis, such as eczema or tinea versicolor.

Hypopigmented Tinea Versicolor

This disorder is frequently mistaken for vitiligo vulgaris. Patients with active, untreated tinea versicolor have a whitish scale.

In addition, under Wood’s lamp examination, the lesions may appear as a yellow-orange fluorescence, and skin scrapings tested with potassium hydroxide are positive for the hyphae and spores of the responsible yeast. Inactive, or postinflammatory, spots of tinea versicolor lack scale and are hypopigmented (see Chapter 7, “Superficial Fungal Infections”).

Chemical Leukoderma

This develops on the hands of persons who work with germicidal detergents or with certain rubber-containing compounds that destroy melanocytes.

The diagnosis is established based on the location of the lesions (e.g., only on the hands) and a history of exposure (Fig. 14.5).

Leprosy

Cutaneous leprosy often manifests with areas of hypopigmentation. The lesions may appear as hypopigmented macules, plaques, or nodules that become insensitive to touch.

Leprosy is extremely rare in the United States, but it may be seen occasionally in patients who emigrate from endemic areas, such as India or parts of South and Central America.

Treatment options for vitiligo include repigmentation therapies for the macules and depigmentation of the remaining healthy skin in patients with extensive disease.

If administered early to patients with limited disease, potent (class 2) and superpotent (class 1) topical corticosteroids are occasionally helpful in promoting repigmentation.

The hands and feet respond poorly to this treatment as well as other therapies mentioned in this section.

Less potent topical steroids such as 1% hydrocortisone should be used on eyelid skin.

Reports of repigmentation have been noted in some patients who applied tacrolimus (Protopic) 0.1% ointment or picrolimus (Elidel) 1% cream twice daily for 2 to 3 months.

Photochemotherapy (see Chapter 3, “Psoriasis”), using psoralens and natural sunlight or psoralens and ultraviolet A light (PUVA) in a phototherapy light box, is sometimes tried. However, this treatment is time-consuming and often ineffective. It should generally not be used for children younger than 9 years.

The treatments are 50% to 70% successful in restoring some color on the face, trunk, and upper arms and legs.

Again, the hands and feet respond poorly to this method.

Narrow-band UVB and excimer laser therapy are expensive and not readily available.

Surgical transplants may be attempted. The following methods may be tried for small, stable areas of vitiligo.

Punch grafts: Punch biopsy specimens from a pigmented donor site are transplanted into depigmented sites, however, a residual, pebbled pigmentary pattern may result.

Minigrafting: Small donor grafts are inserted into incisional recipient areas of vitiligo and held in place with pressure dressings. As with punch grafting, this procedure does not result in total return of normal pigment, and a mottled pigmentation may result.

Special cosmetic makeup that is formulated to match the patient’s normal skin color (e.g., Dermablend or Covermark) or self-tanning compounds that contain dihydroxyacetone may effectively hide the white patches.

Sunscreens can be used to avoid exacerbating the contrast between normal skin and lesions and to protect the lesions, which are sensitive to the sun.

If attempts at repigmentation do not produce satisfactory results, depigmentation may be attempted in selected patients. Those with extensive vitiligo (more than 50% loss of pigment) may elect to have the remaining skin “bleached” with Benoquin (20% monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone). The results are permanent (Fig. 14.6).

Health care professionals should resist the tendency to trivialize vitiligo by referring to it as simply a cosmetic disorder.

Patients should be urged to use sunscreens whenever they are exposed to the sun. By minimizing tanning, sunscreens lessen the contrast between healthy skin and lesions; they also protect the vitiliginous skin, which is sensitive to the sun.

If indicated by positive findings in the patient’s history or physical examination, screening of vitiligo patients for autoimmune diseases should be done; however, the frequency of these associations is not sufficiently high to warrant routine blood tests.

Response rates to treatments for vitiligo often are disappointing, and lesions on the backs of the hands and feet are very resistant to therapy.

Clinicians should be sensitive to patients who have emigrated from countries in which leprosy is endemic—and generally dreaded. Such patients may feel particularly embarrassed and stigmatized by focal areas of lightened skin color, regardless of the cause of the hypopigmentation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree