Periorbital rejuvenation requires a careful understanding of the interplay between the eyelids, brow, forehead, and midface. Reversing periorbital signs of aging requires a correction of volume loss, soft tissue ptosis, and skin changes. Many surgical and nonsurgical techniques exist to treat the aging periorbital region; however, careful consideration of the patient’s complaints and existing anatomy is critical to achieving a safe and esthetically pleasing outcome.

Key points

- •

The periorbital region plays an important role in human social interactions; it effectively communicates not only emotion but also frequently the human condition.

- •

The evaluation and treatment of the aging face in the periorbital region necessitate careful consideration of its function and anatomy.

- •

There are many changes to the skin, bone, and soft tissues of the face that are associated with aging: bony atrophy, lipoatrophy, and descent of facial soft tissues.

- •

Many surgical and nonsurgical techniques exist to treat the aging periorbital region; however, careful consideration of the patient’s complaints and existing anatomy is critical to achieving a safe and esthetically pleasing outcome.

Introduction

The evaluation and treatment of the aging in the periorbital region necessitate careful consideration of its function and anatomy. The periorbital region plays an important role in human social interactions. It effectively communicates not only emotion but also frequently the human condition. As the periorbital region is one of the first parts of the face to show signs of aging, a frequent complaint is that the patient appears tired, sad, or angry.

The periorbital region is composed of the upper and lower eyelids and eyebrow. This region is bounded by the glabella medially, the forehead superiorly, the temple laterally, and the midface inferiorly. Because of the complex interplay between these facial subunits, safe and effective periorbital surgery requires an understanding of the structural changes of this region with aging and a mastery of the anatomy of the orbit, midface, forehead, and brow. The eyebrow and upper eyelid are so intimately intertwined in their function and esthetics that they are considered 2 parts of a continuum: requiring careful consideration of one when treating the other. The lower eyelid and midface share a similar relationship albeit to a lesser degree. This article details the principles and techniques for treatment of the periorbital region with respect to the upper face and midface; the discussion of the latter will be limited to the aspects that directly impact the periorbital region.

Introduction

The evaluation and treatment of the aging in the periorbital region necessitate careful consideration of its function and anatomy. The periorbital region plays an important role in human social interactions. It effectively communicates not only emotion but also frequently the human condition. As the periorbital region is one of the first parts of the face to show signs of aging, a frequent complaint is that the patient appears tired, sad, or angry.

The periorbital region is composed of the upper and lower eyelids and eyebrow. This region is bounded by the glabella medially, the forehead superiorly, the temple laterally, and the midface inferiorly. Because of the complex interplay between these facial subunits, safe and effective periorbital surgery requires an understanding of the structural changes of this region with aging and a mastery of the anatomy of the orbit, midface, forehead, and brow. The eyebrow and upper eyelid are so intimately intertwined in their function and esthetics that they are considered 2 parts of a continuum: requiring careful consideration of one when treating the other. The lower eyelid and midface share a similar relationship albeit to a lesser degree. This article details the principles and techniques for treatment of the periorbital region with respect to the upper face and midface; the discussion of the latter will be limited to the aspects that directly impact the periorbital region.

Esthetics and aging

There are many changes to the skin, bone, and soft tissues of the face that are associated with aging ( Box 1 ). Facial aging is due to bony atrophy, lipoatrophy, and descent of facial soft tissues. The esthetic ideal for the forehead and eyebrow is a subjective and controversial topic. Because of gender, ethnic, and age-related variations, there are many published statements of the esthetic ideal. Westmore’s ideal female brow position, one of the most popular ideal female brow positions, locates the peak at the lateral limbus. However, current trends place the brow’s peak at a more lateral position closer to the lateral canthus. Given the variance in opinions, an honest dialogue between the patient and surgeon is imperative in establishing a plan of treatment that is both acceptable and achievable.

Bony remodeling/atrophy

Volume loss

Brow ptosis

Upper eyelid ptosis

Dermatochalasis

Lacrimal gland prolapse

Fat prolapse

Fat atrophy

Temporal hollowing

Periorbital hollowing

Rhytids

Skin laxity/thinning

In youth, there is a smooth transition from the lower eyelid to the cheek. Ideally, the midface convexity is uniform and relatively free of concavities. With aging, there is a loss of continuity due to contour irregularities and volume differences. The bony orbital rim becomes more pronounced due to inferior displacement of midfacial fat caused by ptosis and atrophy combined with the increased prominence of orbital fat and bone superiorly. In the midface, the position of the malar fat pad is the primary distinction between the youthful face and the aging face. In the youthful face, the malar fat pad should be positioned overlying the zygomatic arch and the orbital component of the orbicularis oculi muscle. Inferiorly, the malar fat pad should be at, but not extending beyond, the nasolabial fold.

Preoperative assessment

Preoperative assessment and planning are critical to achieving safe and effective results. Prior history of facial nerve injury or weakness, neurotoxin injection, facial surgery, or trauma should be elicited. The choice of the rejuvenation technique depends on the patient’s presenting complaints and anatomy, including scalp hair, eyebrow hair, hairline position and shape, forehead length, forehead shape, hairstyle, quality of skin, jowls, depth of nasolabial folds, malar contour, and degree of lift needed. There are additional considerations that should be made when assessing the forehead, brow, and upper eyelids ( Boxes 2 and 3 ). The principle of Hering’s law, which describes the symmetric motor innervation of bilateral levator and frontalis muscles, should also be taken into account, especially when encountering unilateral ptosis or asymmetry. Depending on the patient’s needs, a combination of treatment approaches to the brow, forehead, and midface may be implemented.

Assessing the upper third of the face

Brow ptosis

Brow shape

Upper eyelid ptosis

Dermatochalasis

Rhytids

Hairline (shape, position)

Forehead length

Asymmetry (brow, eyelid, hairline, rhytids)

Skin quality

Assessing the middle third of the face

Lower eyelid position (entropion, ectropion)

Negative vector orbit

Volume (bony, soft tissue)

Tear trough

Midfacial rhytids

Asymmetry (midface, eyelid, rhytids)

Skin quality

In addition to recognizing the esthetic and surgical issues, a detailed history of pre-existing ocular conditions, such as prior ophthalmologic surgery, chronic lid infections, ptosis, or refractive errors, is an important part of the initial assessment. A complete medical history should be elicited to discover any comorbidities that may have ocular manifestations. The physical examination of the patient may also include visual acuity, extraocular muscle assessment, visual fields, lacrimal secretion, corneal sensation, pupillary assessment, lower eyelid position, margin gap, and the presence or absence of a Bell phenomenon. Assessment of the marginal reflex distances (MRD1, MRD2) may be useful in assessing for ptosis and ectropion. MRD1 is the distance from the pupillary light reflex to the upper eyelid. MRD2 is the distance from the pupillary light reflex to the lower eyelid. The margin gap is the distance between the margin of the upper and lower eyelid with involuntary blink and maximal effort. The palpebral fissure height is the distance between the upper and lower eyelid in primary gaze.

Forehead and brow

Anatomy

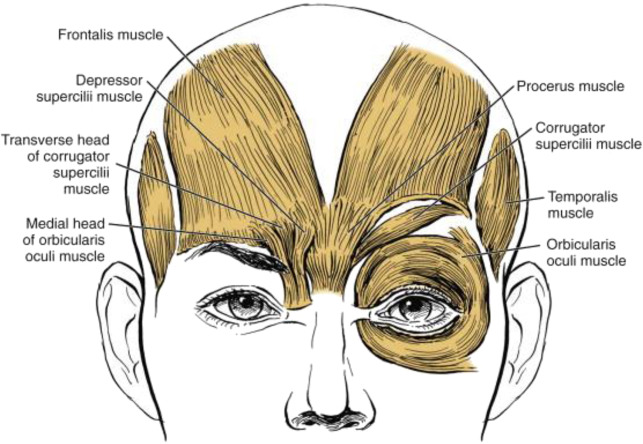

The eyebrow extends from the glabella medially to the temporal region laterally. The skin and soft tissues of the eyebrow overly the superior orbital rim. The hair of the eyebrow is unique from that of the scalp. These hair follicles have a limited potential for growth and regeneration following injury. The hair of the eyebrow imparts much of the apparent shape to the brow: flat, arched, or sloping laterally. Men typically have thicker brows than women. The female brow is generally more superiorly located with a greater arch. The male brow is generally lower on the superior orbital rim and flatter. The brow contour may be prominent with robust soft tissue and bony contour or flat with atrophy. The muscles of the eyebrow region include the orbicularis oculi, procerus, corrugator supercilii, and depressor supercilii. These muscles are all depressors of the eyebrow and are innervated by the facial nerve. The orbicularis oculi is divided into 3 components (pretarsal, preseptal, orbital) as defined by the periorbital structure that it overlies. The procerus muscle spans the nasion to the midline glabella and is responsible for inferior displacement of the medial brow and horizontal glabellar rhytids ( Fig. 1 ). The corrugator supercilii muscle spans the medial superciliary ridge to the lateral third of the brow and is responsible for inferomedial displacement of the medial brow and vertical glabellar rhytids. The depressor supercilii muscle spans the frontal process of the maxilla to the superior medial canthal region and is responsible for inferior displacement of the medial brow and oblique glabellar rhytids. The frontalis muscle is responsible for brow and forehead elevation and is innervated by the temporal branch of the facial nerve. The frontalis muscles span the galea aponeurotica anteriorly, occipitalis muscles posteriorly, and the temporal fascia laterally. Contraction of the frontalis muscle creates the horizontal rhytids of the forehead region.

The forehead extends from the superior aspect of the eyebrow inferiorly to the hairline superiorly. Laterally, the temporal region bounds the forehead. The forehead shape is impacted by the position of the eyebrows and the hairline. The average male hairline height is 6.5 to 8 cm, whereas the average female hairline height is 5 to 6 cm. The forehead contour may be sloping posteriorly, flat, or protruding anteriorly. The forehead is composed of several layers of soft tissue: skin, connective tissue, aponeurosis, loose areolar tissue, galea, and periosteum.

Surgical Anatomy

- •

The frontal branch of the facial nerve provides motor innervation to the upper face. The path of this motor nerve has been well described ( Fig. 2 ). The frontal branch generally follows a path outlined by 2 points: (1) midpoint between the tragus and the lateral canthus; (2) inferior border of the ear lobule. During surgical dissection of this region, sentinel veins penetrate the soft tissues from deep to superficial at the general location of the frontal branch. At the zygomatic arch, the frontal branch remains deep to the subcutaneous musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS), but as it traverses the arch superiorly, it moves into a more superficial location. Dissection in the plane between the temporoparietal fascia and the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia will protect and preserve the frontal branch.

Fig. 2

The path of the frontal branch of the facial nerve follows a line drawn through 2 points: (A) midpoint between the tragus and the lateral canthus; (B) inferior border of the ear lobule.

- •

The supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves exit the superior orbital rim via a notch or complete foramen at 17.5 mm and 27.5 mm from the midline. These nerves travel with accompanying arteries and veins. Great care should be taken to preserve these neurovascular bundles during dissection. The arteries are branches of the internal carotid artery system via the ophthalmic artery. Great care should be taken to avoid intraluminal injection of local anesthetic, which has the potential for blindness.

- •

The retro-orbicularis oculi fat extends from the preseptal portion of the eyelid to the subbrow region overlying the superior orbital rim. Removal or manipulation of this tissue should be performed with care to avoid orbital hollowing, which often exacerbates the appearance of aging.

- •

The conjoint tendon is composed of the condensation of the deep temporal fascia, superficial temporal fascia, and the periosteum of the periorbital region ( Fig. 3 ). The conjoint tendon and arcus marginalis must be released in order to achieve an adequate brow lift.

Fig. 3

Fascial layers of the temporal region. CSM, corrugators supercilii muscle; DG, deep galea plane; DTF, deep temporal fascia; FM, frontalis muscle; SON-D, deep division of the supraorbital nerve; SON-S, superficial division of the supraorbital nerve; STF, superficial temporal fascia; STF I, the superficial layer of the temporal fascia; STF II-III, the 2 deep layers of the superficial temporal fascia; TB, temporal branch of frontal nerve; TM, temporalis muscle.

( From Lam VB, Czyz CN, Wulc AE. The brow-lid continuum: an anatomic perspective. Clin Plast Surg 2013;40:8; with permission.)

Surgical Techniques

Endoscopic brow lift

- •

The endoscopic brow lift is the generally preferred surgical technique in the author’s practice. The excellent scar camouflage, superb endoscopic visualization, relatively atraumatic tissue dissection, and decreased operative time make this technique the optimal choice in most patients.

- •

This procedure may be used with equal benefit in men and women. The forehead length is generally stable, and scalp anesthesia is minimal.

- •

The incisions are typically placed within the hairline: midline, 2 paramedian incisions. Two additional oblique temporal incisions are added for a lateral dissection over the temporalis, if a temporal brow lift is to be performed in conjunction with the brow lift (see later discussion).

- •

The dissection is performed in either a subperiosteal or a subgaleal plane.

- •

Soft tissue suspension is performed using screws (absorbable and nonabsorbable), bone tunnel with sutures, or a fixation device, such as Endotine or Ultratine (MicroAire, Charlottesville, VA, USA).

- •

The disadvantages include decreased precision with brow placement, the need for endoscopic equipment setup, and possible scalp anesthesia posterior to the incisions. In addition, this technique has the potential to noticeably lengthen the forehead and should be used with caution in patients with high or receding hairlines. The endoscopic visualization may be limited in patients with a round forehead contour.

Temporal brow lift

- •

The temporal brow lift is an excellent choice for patients with isolated lateral brow ptosis. This procedure may be performed through an open or endoscopic approach. In the endoscopic approach, the supraorbital neurovascular bundle is usually the medial extent of the dissection. The technique is otherwise very similar to the endoscopic brow lift described above.

- •

In the open approach, the incision is placed at or directly anterior to the temporal hairline, and the dissection may be performed in a subcutaneous, subperiosteal, or subgaleal plane. Excess skin and soft tissue are excised from the anterior forehead skin flap.

- •

The disadvantages include scar visibility, alopecia at the incision, and scalp anesthesia posterior to the incision.

Direct brow lift

- •

The direct brow lift allows for precise control of brow shape and placement with minimal tissue dissection.

- •

This procedure is best suited for elderly patients with forehead rhytids and bushy eyebrows. It is also often used in patients with facial paralysis.

- •

The incision is placed directly at or within the superior margin of the eyebrow.

- •

The dissection is performed in a subcutaneous plane. Excess skin is excised from the superior aspect of the incision.

- •

The orbicularis oculi muscle is usually suspended to the periosteum superiorly using braided, absorbable polyglycolic acid suture.

- •

The disadvantages include scar visibility and possible recurrence of brow ptosis due to persistent brow depressor function.

Mid-forehead brow lift

- •

The mid-forehead brow lift also allows for precise placement of the brow with minimal tissue dissection.

- •

This procedure is best suited for patients with deep forehead rhytids or facial paralysis. It is also a good option for patients with a receding hairline.

- •

The incisions are made bilaterally but should not interconnect or cross the midline. They should not be linear but should adhere to the contour of a deep forehead rhytid.

- •

The dissection is performed in a subcutaneous plane. Excess skin is excised from around the forehead rhytid.

- •

The orbicularis oculi muscle is usually suspended to the periosteum superiorly using braided, absorbable polyglycolic acid suture.

- •

The disadvantages include scar visibility and possible recurrence of brow ptosis due to persistent brow depressor function.

Pretrichial/Trichophytic brow lift

- •

The pretrichial, or trichophytic, brow lift is a good option for patients who need brow and forehead lifting to address brow ptosis and forehead rhytids.

- •

This procedure is an excellent choice for patients with a long forehead and high frontal hairline. This approach does not lengthen the forehead, but rather shortens it and offers the potential for excellent scar camouflage. In addition, this technique offers added lift to the forehead for the treatment of forehead rhytids.

- •

The incision is placed at or directly anterior to the frontal hairline. The incision is irregular and beveled posterior to anterior to allow for the hair growth through the scar for improved scar camouflage.

- •

The dissection is performed in a subperiosteal or subgaleal plane. Excess skin and soft tissue are excised from the anterior forehead skin flap.

- •

The disadvantages include scar visibility, alopecia at the incision, and scalp anesthesia posterior to the incision.

Coronal brow lift

- •

The coronal brow lift is another option for patients who need brow and forehead lifting to address brow ptosis and forehead rhytids.

- •

This procedure is best suited for women with a short forehead.

- •

The incision is placed posterior to the hairline and follows the contour of the frontal and temporal hairline.

- •

The dissection is performed in the subgaleal plane. Excess skin and soft tissue are excised.

- •

The advantages include excellent scar camouflage at the incision.

- •

The disadvantages include forehead lengthening, alopecia at the incision, and scalp anesthesia posterior to the incision.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree