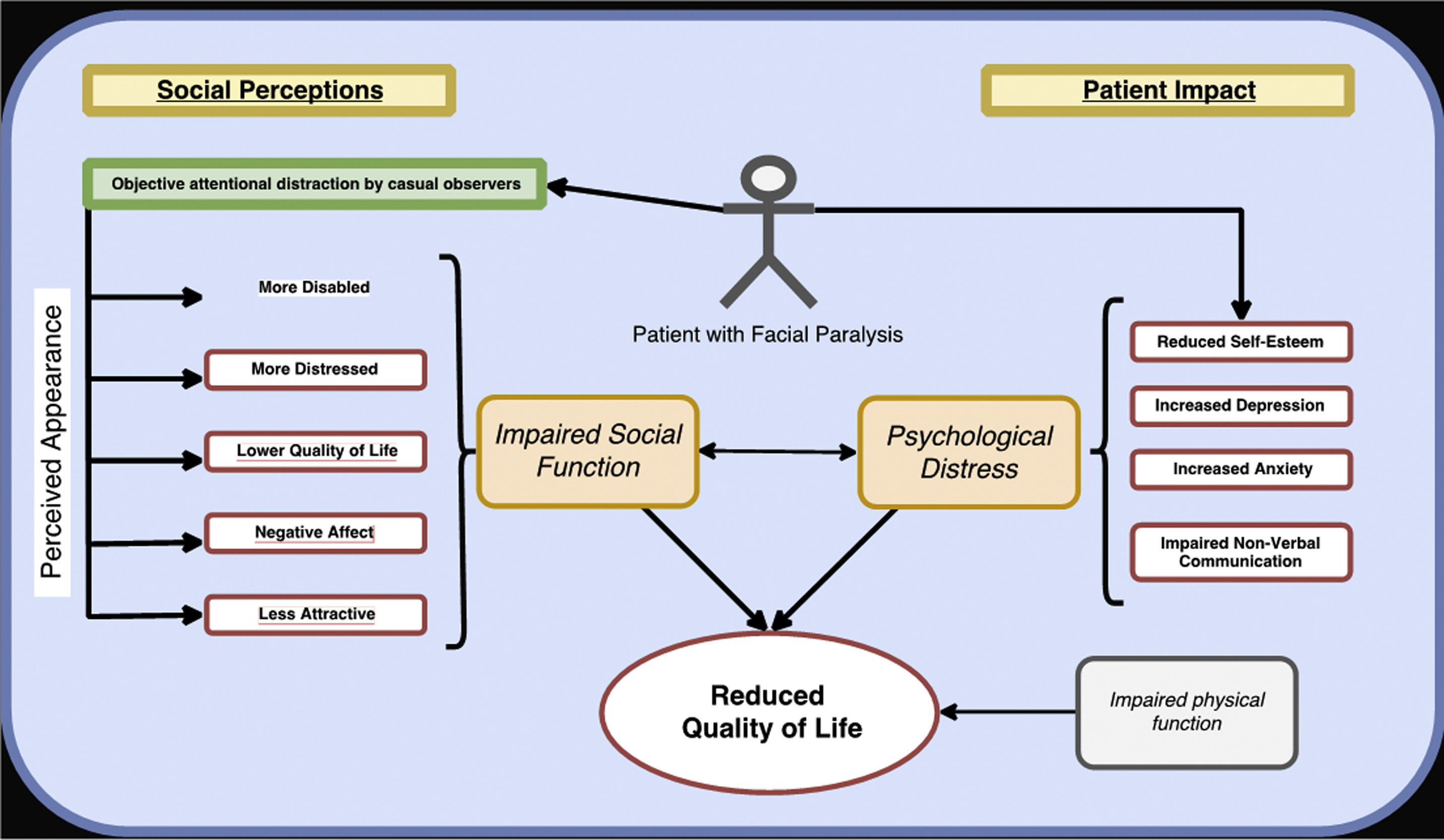

The goal of this article is to better understand the social impact of facial paralysis. Patients with facial paralysis may suffer from impaired social interactions, disruption of self-concept, psychological distress, and decreased overall quality of life. Vigilance in detecting patients suffering from mental health issues may result in providing early referral for psychological evaluation and psychosocial support resources complementing facial reanimation treatment.

Key points

- •

Patients with facial paralysis suffer significant morbidity in social functioning because of the observed deformity at rest and ineffective movement. They are perceived as less attractive, having a more negative affect, and having a lower quality of life by observers in society.

- •

Individuals with facial paralysis may suffer from reduced self-esteem, increased anxiety, worse depression, and reduced quality of life.

- •

In treating patients with facial paralysis, social well-being should be an important consideration by the provider. The degree of facial dysfunction is predictive of the degree of casual observer perceived disfigurement, and thus, the social burden of the condition.

- •

Facial reanimation may assist in decreasing the psychosocial morbidity of facial paralysis.

- •

Early detection of mental health issues in patients with facial paralysis may improve overall care of this patient population.

Background

Role of the Face

As an important factor in social interactions, the human face provides nonverbal cues regarding one’s identity, sex, age, race, affect, and overall health. Inferences are made by observers within 100 to 200 milliseconds of exposure to the face. These inferences are made from both static features of the face, such as attractiveness (composed of age, symmetry, sexually dimorphic shape cues, averageness, and skin color/texture) and disfigurement. This inference is evolutionarily rooted in humans in order to judge reproductive fitness of others and to identify threats. Facial movement is also fundamental in the interpersonal exchange between individuals. Individuals engaging in social interaction subconsciously mirror each other’s facial expressions, resulting in emotional contagion and tacit psychosocial perceptions. In addition, participants in the social exchange use facial expression to foster coherence and integration of information and emotions, such as interest or apprehension. ,

Patients who develop facial deformity sustain a loss of physical function, such as the inability to speak or eat, and notably psychosocial function related to negative social perceptions. An example of such facial deformity is facial paralysis, which impairs facial movement, resulting in resting asymmetry that becomes highlighted when engaging in social interactions.

A negative social bias against those with visual facial differences permeates various cultures and time. Shaw described examples of global prejudice to individuals with facial deformity, such as mothers rejecting children with cleft lip, the King of Denmark in 1708 forbidding interaction with people with facial deformity, and African tribes prohibiting people with facial deformity from becoming chief. Accordingly, patients with facial paralysis have impaired facial expression, resulting in negative social ramifications. This article aims to discuss the social implications of facial paralysis and provides a basis for improving patient care beyond treating physical function.

Social implications of facial paralysis

Psychology literature in the analysis of facial movements and expressions is vast. Studies have more specifically looked at how casual observers assess the faces of individuals with facial paralysis. Using infrared eye-gaze tracker technology to record observers gazing on paralyzed and normal faces, Ishii and colleagues found that casual observers gaze on a paralyzed face differently, with greater attention to the mouth, compared with a normal face, especially when smiling. Furthermore, Helwig and colleagues characterized using an anatomically realistic 3-dimensional facial tool to study the spatiotemporal properties of smiles. It was found that the amount of dental show should be balanced to the smile extent and mouth angle and that timing asymmetries of smile onset can be detrimental to smiling effectiveness.

Casual observers perceive static images of a paralyzed face as having a more negative affect display when compared with images of nonaffected faces. When assessing videos of movement, observers perceived individuals with severe facial paralysis as much less happy than those with mild facial paralysis, demonstrating that observers misperceive a face lacking expression. Beyond negatively impacting affect display, several studies found negative social perceptions across other domains. Ishii and colleagues tasked casual observers to identify a paralyzed face and rate the attractiveness as compared with normal faces, finding that paralyzed faces were rated as significantly less attractive. In addition, a smiling expression from patients was found to be unnatural by observers. Additional studies have found that patients with facial paralysis appear distressed, less trustworthy, less intelligent, and abnormal. Interestingly, Li and colleagues distinguished between the various isolated regional facial paralysis presentations, finding that isolated zygomatic nerve palsy (ie, inability to close eye) results in the highest social detriment, and frontal palsy has the lowest social detriment.

Observer perception is not congruent with individual self-perception. Observers rated the quality of life of patients with facial paralysis to be worse than the individual’s own self-assessment. In addition, studies have found that physician experts also perceive patients with facial paralysis as having reduced attractiveness, increased severity, and worse perceived quality of life compared with how patients perceive themselves. In the context of an individual’s self-concept, the social perception morbidity of facial paralysis has related negative impact on his or her psychological well-being.

Impact of Facial Paralysis on Patients

Acquired facial paralysis has a negative effect on an individual’s psychological well-being. Several studies have investigated quality of life, depression, anxiety, and other psychosocial factors associated with facial paralysis. Ryzenman and colleagues found that 30% of patients were significantly distressed by facial paralysis after acoustic neuroma surgery. In an effort to understand the effect of facial paralysis resulting from other causes, investigations have found that patients with facial paralysis after parotidectomy suffer a decrease of quality of life in the first 3 months, but quality of life does improve after 1 year. Nevertheless, most patients in the study had full recovery of nerve function by that time. , Also, patients with Bell palsy have been found to report lower quality of life compared with patients with facial paralysis after acoustic neuroma resection. In examining other factors, studies have found that increased facial paralysis severity, younger age, and female gender are associated with worse psychosocial patient-reported scores. Interestingly, these findings were not found in pediatric patients with congenital facial paralysis.

Although various factors influence quality of life, psychological distress can be associated with facial paralysis and potentially related to the social implications. Fu and colleagues and Bradbury and colleagues surveyed patients with facial paralysis and found that 31% to 60% of patients had significant depression and anxiety. Notably, patients with depression were more likely to be dissatisfied with reconstructive procedures. However, these studies had not compared the prevalence of depression compared with controls. A prospective observational study found patients with facial paralysis suffered from worse depression, especially if the severity was House-Brackmann grade 3 or higher, lower mood, lower self-reported attractiveness, and lower quality of life compared with control patients.

There are several evolutionarily engrained functions of facial expressions and affect. As related to psychosocial distress, it is suggested that the ability to express an emotion is related to an individual’s ability to recognize emotion implying an additional hurdle for social interactions for these patients. For example, individuals who received botulinum toxin treatment of the “scowling” muscles, the procerus and corrugators, showed less activity in the amygdala (the emotional area of the brain) when viewing angry faces. Similarly, patients with Moebius syndrome have been found to have difficulty recognizing facial identities and facial expressions. In a similar way, the ability to express a facial emotion also intensifies the experience of that emotion. This “facial feedback,” as described by Lewis and Ekman, results from a centrally generated facial expression, for example, smiling resulting in a positive mood and scowling resulting in a negative mood. Facial mimicry, the manner by which an individual reflects another’s expression on their own face, is important for social interactions and is also attenuated. Patients thus do not effectively communicate nonverbally with facial cues and also suffer challenges in interpreting those cues from and connecting with others.

Setting patient care goals

It is important that providers consider the social morbidity experienced by patients with facial paralysis and visual facial differences. The social dimension is one not often explored in the clinic setting, but is fundamental to the well-being of the individuals we treat. Treating these patients must go beyond corneal health, speech, and eating and must include treatments to minimize disfigurement and optimize nonverbal communication.

The first step is to discuss the social dimension in the consultation. We can now predict the social burden of the paralysis by the clinical degree of facial function ; this helps discuss and determine treatment goals with each individual patient.

When treating patients with facial paralysis, facial reanimation can achieve many goals. These goals include resting symmetry, eyelid closure for corneal protection, restoration of smile, improved brow posture, oral competence, and return of voluntary facial movement. For movement, the goal is to achieve spontaneous facial movement that is absent of synkinesis or mass movement. Beyond physical functions, understanding the potential psychosocial benefits, and limitations, of facial reanimation facilitates discussions with patients about surgical interventions and rehabilitation to achieve the goals mentioned above.

Facial reanimation has been found to improve function in the psychosocial dimension. Several studies have aimed to understand how facial reanimation surgery restores normal facial function and improves social perceptions of patients with facial paralysis. Using eye-gaze tracking technology, a study found that facial reanimation surgery restores how observers gaze patterns to normal. In a study comparing observer perceptions of patients having undergone surgery to treat facial paralysis, patients sustain a significant improvement in affect display, especially when smiling. Furthermore, facial reanimation improves patient attractiveness, but does not return them completely to premorbid baseline as compared with controls. A subsequent study found that observers highly value facial reanimation surgery with a mean willingness to pay per quality-adjusted life year of $10,167 for low-grade facial paralysis and $17,008 for high-grade facial paralysis.

In addition to improving social perceptions, facial reanimation improves psychosocial health of patients with facial paralysis. Lindsay and colleagues demonstrated that patients report significantly improved quality of life and FaCE scores after free gracilis muscle transfer. In addition, botulinum toxin treatment of facial synkinesis significantly improves patient quality of life. ,

Considerations

The psychosocial implications of facial paralysis emerge from the influence on how patients interact with society. Notably, patients suffer from the loss of civil inattention, a disturbance in self-concept, and negative experiences with social interactions, resulting in lower quality of life. These consequences result from the multitude of aforementioned factors.

As described above, individuals interacting with patients with facial paralysis enter social interactions with a negative bias. The static facial deformity marked by asymmetry and the dynamic lack of expression pose significant obstacles to social well-being of patients.

Patient and provider education and understanding of the basic muscular and spatiotemporal facets of facial expressions and affect display are key to success. With this knowledge, providers should consider the following:

- 1.

Restore dynamic function to the face whenever possible.

- •

Prioritize reanimating the smile, as it forms the basis of positive affect display, positive emotional experience, and a social cue for motivation of interpersonal interactions.

- •

- 2.

Reduce facial disfigurement

- •

Improve facial symmetry, reconstruct facial contour deformities, reduce stigma of illness leading to paralysis (ie, inject the contralateral intact brow and corrugators, perform fat grafting, perform scar revision).

- •

- 3.

Improve attractiveness

- •

Consider procedures that will enhance attractiveness in order to improve favorable inferences and first impressions of your patients (ie, facial and skin rejuvenation procedures).

- •

- 4.

Reduce negative facial cues

- •

Work to reduce aspects of facial position that are inferred as negative (that is, elevate the ptotic brow surgically, treat the glabella with botulinum toxin in the corrugators, chemodenervate the platysma and depressor anguli oris in synkinetic patients, treat the buccinator in synkinesis, as it can signal irony and contempt when used with zygomaticus).

- •

- 5.

Address emotional well-being

- •

Screen for depression and adjustment disorder in patients and refer for treatment if needed.

- •

- 6.

Train patients

- •

Rehabilitate patients with the knowledge of social inferences (ie, train to reduce asymmetry in smile onset, practice to maximize dental show in the context of smile extent and mouth angle, reduce constrained smiles, as they can be misinterpreted as contempt, educate on appropriate social cues with expected reciprocal facial movements).

- •

Summary

Facial paralysis has a significant psychosocial impact on patients ( Fig. 1 ). Patients suffer from having negative observer perceptions, disruptions of self-perceptions, and impaired social interactions. As a consequence, patients have impaired social function, altered self-concept, psychological distress, and reduced quality of life. Fortunately, facial reanimation can help alleviate some of the psychosocial burden of facial paralysis. Nonetheless, treating physicians should be vigilant regarding identifying psychological distress and consider referral for evaluation and treatment if necessary.