42 Pediatric tumors

Synopsis

Pediatric tumors are highly varied in origin, pathophysiology, and clinical presentation.

Pediatric tumors are highly varied in origin, pathophysiology, and clinical presentation.

These tumors can be highly malignant or benign masses with complex presentations and can be grouped and treated based on their growth characteristics and local complications.

These tumors can be highly malignant or benign masses with complex presentations and can be grouped and treated based on their growth characteristics and local complications.

Pediatric masses can also be embryological tissue remnants or have their origin due to errors along the pathways of embryological development.

Pediatric masses can also be embryological tissue remnants or have their origin due to errors along the pathways of embryological development.

These masses can commonly present as acute or chronic reactions to infections, leading to lymphadenopathy.

These masses can commonly present as acute or chronic reactions to infections, leading to lymphadenopathy.

Neurofibromatosis

Introduction

Neurofibromatoses are a set of inherited disorders comprising neurofibromatosis-1 (NF-1), NF-2, and schwannomatosis. All of these lead to the formation of benign nerve sheath tumors.1

Basic science/disease process

NF-1 is an autosomal-dominant disorder with complete penetrance and variable expression. Chromosome 17 is involved. The incidence is 1/3000, and the average age of children at the time of presentation is 7 years.1–3

The discussion below pertains mainly to the treatment of various clinical features of NF-1.

Café-au-lait spots

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Café-au-lait spots are characterized as cutaneous, hyperpigmented lesions, typically 20–30 mm in diameter. They contain keratinocytes with increased macromelanosomes. Greater than six lesions are found in 90–99% of cases.4,5

Lisch nodules

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Lisch nodules are dome-shaped, melanocytic hamartomas found on the surface of the iris.4,5 They appear around age 10, and are present in nearly all people with NF-1 by age 20.

Optic nerve gliomas

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Optic nerve gliomas are the most common central nervous system tumors in NF-1 patients. They occur in 15% of cases and are histologically identified as low-grade pilocytic astrocytomas.4,5,8 They are relatively indolent and sometimes asymptomatic. If symptomatic, they can cause proptosis, squint, abnormal color vision, visual field loss, pupillary abnormalities, and hypothalamic dysfunction.7

Glomus tumors

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Glomus tumors are usually solitary lesions, but occur in multiples in individuals with NF-1. They present under fingernails with symptoms of cold sensitivity and increased localized tenderness.10

Craniofacial manifestation

Diagnosis/patient presentation

In the craniofacial region, the orbitotemporal area is most commonly involved. Orbitotemporal neurofibromatosis-associated skeletal malformations and deformities include11–17:

• sphenoid wing hypoplasia, which leads to expansion of the middle cranial fossa into the posterior orbit and causes proptosis

• remodeling and/or decalcification of the posterior orbit

• supraorbital tumors, which cause defects of the orbital roof and lead to a downward and outward displacement of the globe

• thinning of the lateral and inferior orbital rims

• depression of the orbital floor and elevation of the orbital roof and supraorbital rim, which increases orbital volume

• dysplasia and downward dislocation of the zygoma

• progressive plexiform neurofibromatosis of the temporal area, which leads to continued enlargement of the eyelids, excessive mechanical ptosis, pulsating proptosis, eye pain, and epiphora.

Treatment/surgical technique

Treatment is based on Jackson’s classification11,14:

• Article I. Class 1: significant soft-tissue involvement with minimal bone involvement and normal vision

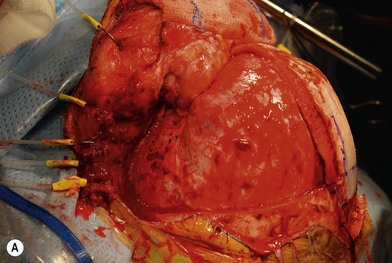

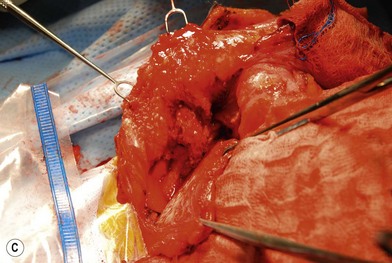

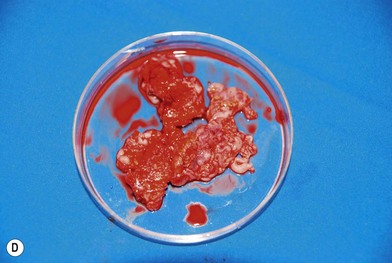

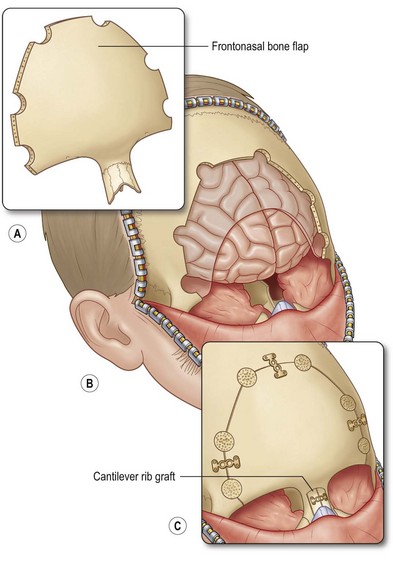

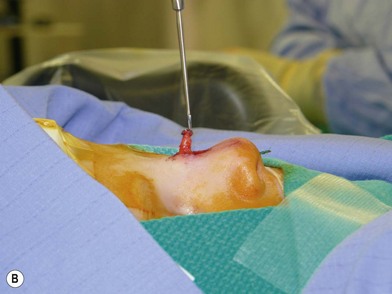

Treatment involves debulking of the soft-tissue component of the tumor through an anterior, lateral, or anterolateral orbitotomy. If blepharoptosis is present, levator resection is performed.16 In cases where only a partial resection is carried out, a technique of netting the remaining tissue using Teflon mesh has been proposed18 (Fig. 42.1).

Treatment involves debulking of the soft-tissue component of the tumor through an anterior, lateral, or anterolateral orbitotomy. If blepharoptosis is present, levator resection is performed.16 In cases where only a partial resection is carried out, a technique of netting the remaining tissue using Teflon mesh has been proposed18 (Fig. 42.1).• Article II. Class 2: soft-tissue and bone involvement with normal vision

Treatment involves an intracranial approach for tumor debulking and posterior orbital wall reconstruction.16 After the tumor is debulked, the herniated temporal lobe is reduced and bone grafts, obtained from splitting the contralateral frontal bone, are used to reconstruct the posterior and superior orbital walls. Orbital volume is increased with osteotomies and the globe is elevated by raising the canthal ligaments and building the floor. A two-stage approach has been suggested in which the intracranial portion of tumor debulking and orbital reconstruction is completed in stage 1. A second-stage procedure is performed in which subcutaneous debulking, eyelid, face, and orbital reconstruction is completed19 (Fig. 42.2).

Treatment involves an intracranial approach for tumor debulking and posterior orbital wall reconstruction.16 After the tumor is debulked, the herniated temporal lobe is reduced and bone grafts, obtained from splitting the contralateral frontal bone, are used to reconstruct the posterior and superior orbital walls. Orbital volume is increased with osteotomies and the globe is elevated by raising the canthal ligaments and building the floor. A two-stage approach has been suggested in which the intracranial portion of tumor debulking and orbital reconstruction is completed in stage 1. A second-stage procedure is performed in which subcutaneous debulking, eyelid, face, and orbital reconstruction is completed19 (Fig. 42.2).• Article III. Class 3: soft-tissue and bone involvement with blindness or an absent globe

Treatment involves debulking the tumor with exenteration. An orbital approach is used to reduce the herniated temporal lobe into the middle cranial fossa. The bony defect is covered with a split-rib/bone graft. The orbital volume is reduced and its position is adjusted with osteotomies and bone grafts. Finally, an orbital prosthesis is fitted.

Treatment involves debulking the tumor with exenteration. An orbital approach is used to reduce the herniated temporal lobe into the middle cranial fossa. The bony defect is covered with a split-rib/bone graft. The orbital volume is reduced and its position is adjusted with osteotomies and bone grafts. Finally, an orbital prosthesis is fitted.

Fig. 42.1 (A, B) Anterior orbitotomy with debulking of left orbitotemporal neurofibromatosis.

(Courtesy of Dr. Delora L. Mount.)

Neurofibromas

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Nerve sheath tumors arise between the dorsal root ganglion and terminal nerve branches.4,5,20 They are composed of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, mast cells, and perineural cells.7,20,21 Localized cutaneous neurofibromas are the most common nerve sheath tumors. They present as multiple slow-growing, pedunculated lesions that progressively increase in prominence.7 These lesions can be surgically excised for symptomatic benefit. This, however, may lead to hypertrophic scarring. The benefits of carbon dioxide laser treatment have not been clearly established. Diffuse cutaneous neurofibromas present as a plaque-like thickening of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, and are most frequently found in the head and neck region. These are nondestructive, soft, compressible lesions that grow along the fibrous septa in children and young adults. Removal of these subcutaneous lesions may lead to neurological deficits in the region of the concerned nerve. Localized intraneural fibromas are the second most frequent type of neurofibroma, and represent fusiform enlargement of peripheral nerves. These are the most common neurofibromas of the upper extremity, and account for 85% of cases.22 Spinal and cranial nerves may also be involved. Massive soft-tissue neurofibromas (elephantiasis neurofibromatosa) lead to distortion of the face and require complete excision.23 Plexiform neurofibromas are composed of nerve sheath cells proliferating along the length of the nerve and are associated with hypertrophy of the overlying soft tissue, hyperpigmentation, and hypertrichosis of the overlying skin. Plexiform neurofibromas occur in 16–40% of patients with NF. These lesions involve the trunk (43–44%), extremities (15–38%), and head and neck (18–42%).20 They are congenital in origin and become evident by 2 years of age. Plexiform neurofibromas are locally destructive lesions that grow during periods of hormonal change, and may involve multiple nerve branches and plexi.24

Treatment/surgical technique

Preoperative contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), angiography, and embolization have been recommended.20,21,22,25 The highly vascular nature of these lesions makes surgical removal complicated.24 Multiple nonsurgical management options, such as farnesyl transferase inhibitors, antiangiogenesis drugs, and fibroblast inhibitors, are being explored.26 Tumors resected in children below the age of 10 years recur in 60% of cases, while those resected above the age of 10 years recur in 30% of cases.27

Malignant degeneration of peripheral nerve sheath tumors

Diagnosis/patient presentation

There is an 8–13% lifetime risk for these tumors to undergo malignant degeneration. This occurs predominantly between the ages of 20 and 35.4,7 Medium and large nerves of the thigh, buttock, brachial plexus, and paraspinous areas are involved. Signs of malignant degeneration include increased pain, new neurological deficits, sphincter disturbance, rapid increase in the size of the neurofibroma, or change in texture.28 Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography helps with the quantification of glucose metabolism in the cells, and can help distinguish between benign and malignant lesions.29,30

Malignant schwannomas (neurofibrosarcomas)

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Neurofibrosarcomas can involve either the cervical vagus nerve or the sympathetic chain and present as parapharyngeal masses, with paresthesia, pain, and muscle weakness.31 They may also be of parotid origin. Children with NF-1 are at increased risk for developing these lesions.32

Fibromatosis colli

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Fibromatosis colli presents as solitary tumors of the sternocleidomastoid muscles (SCM) and are the most common cause of neonatal torticollis. The tumors are first seen between 3 and 4 weeks of age. They develop in the lower portion of the SCM and may involve both sternal and clavicular heads of the muscle. The diagnosis is made through fine-needle aspiration that yields fibroblasts, degenerative atrophic skeletal muscle cells, and numerous giant muscle cells. Natural regression of the tumor is seen during the first 6 months of life. Torticollis is associated with fibromatosis colli in 23–33% of patients and may continue after treatment in 17% of patients because of progressive fibrous replacement of the muscle tissue.35

Treatment/surgical technique

Surgery involves releasing both heads of the SCM through a limited transverse incision. The clavicular head is readvanced and attached to the sternal head to lengthen the muscle and preserve the anatomic landmarks of the sternal column. Surgery is performed on patients in whom torticollis persists for 1 year.36

Infantile digital fibroma

Diagnosis/patient presentation

These generally appear as single or multiple gelatinous or firm nodules on fingers or toes. They are rare and are seen in both males and females. They are generally harmless but are removed because of the discomfort they cause by rubbing on footwear. The diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy that shows spindle-shaped cells and collagen fibers in the dermis. A radiograph is usually taken to determine the extent of the lesion (Fig. 42.3).

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma

Treatment/surgical technique

Treatment involves embolization followed by surgery. A transpalatal, transfacial, midface degloving approach or Le Fort I osteotomy approach can be used. An anterior subcranial approach is used for transcranial lesions.38–40

Dermoids

Nasal dermoids

Basic science/disease process

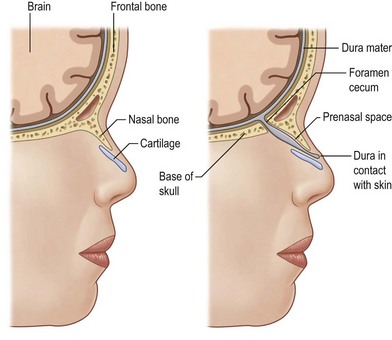

Between the third and eighth week of embryogenesis, when the neural groove deepens to form the neural tube, incomplete sequestration of the neuroectoderm from the somatic ectoderm leads to a persistent connection of the foramen cecum with the fonticulus nasofrontalis, and the foramen cecum with the prenasal space. These connections cause the formation of nasal dermoids, dermal sinuses, gliomas, and encephaloceles.41 Nasal dermoids can be present at any point between the glabella and the base of the columella. Intracranial extension can exist via the tract through the nasal septum and foramen cecum, or through the widened frontonasal suture (fonticulus nasofrontalis) and foramen cecum. In these cases, the presence of the dermoid between the leaves of falx and a bifid crista galli are noted (Fig. 42.4).

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Dermoids present as firm, cystic lesions, or infected persistent abscesses. They expand slowly and cause destruction of the nasal bones and widening of the nasal ridge. MRI can help differentiate between normal anatomic variants of the anterior cranial base versus the intracranial extension of dermal sinus tracts. CT scans can help delineate the bony anatomy of the nose and the cranial base, and help in operative planning with the use of three-dimensional reconstruction.42,43

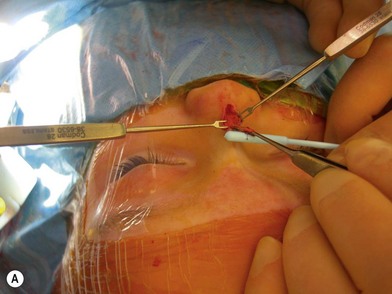

Treatment/surgical technique

Dermoid cysts or sinuses that are present at the columella usually extend to the nasal spine. Resection involves a circumscribed removal of the sinus tract. If a cyst is associated with it, it is dissected through the labial sulcus. Sinuses and cysts that are present from the radix to the nasal tip, but are without intracranial extension, are excised in combination with an open rhinoplasty approach. This approach has been reported to have improved exposure of the osteotomies, the upper lateral cartilages, and the septum44 (Fig. 42.5). A closed rhinoplasty technique has been proposed for the excision of superficial distal nasal-tip dermoids. Since most nasal dermoid cysts are confined to the superficial nasal area, this technique can prove to be beneficial.45 For lesions with suspected/confirmed intracranial extension, failure to excise the tract completely can lead to abscess formation, meningitis, or osteomyelitis.46,47 Multiple approaches have been proposed.48–61 The traditional approach calls for combining an intracranial procedure such as a bifrontal craniotomy, with an extracranial procedure, such as a transverse, vertical, inverted U, lateral rhinotomy, or rhinoplasty to address the entire sinus tract.48,49

Fig. 42.5 (A, B) Excision of nasal dermoid without intracranial extension.

(Courtesy of Dr. Diane G. Heatley.)

A second approach, described as the “keystone” technique, involves a bifrontal craniotomy superior to the supraorbital rims, two paramedian sagittal osteotomies extending down the length of the nasal bones, followed by outfracturing of the keystone component. This technique allows complete exposure of the sinus tract and enhanced exposure of the anterior cranial base.53 A similar subcranial transglabellar approach involves horizontal osteotomies above the suprarorbital rims and at the level of the nasal bones, and vertical osteotomies at the supraorbital rims to expose the intracranial portion of the dermoid. This technique allows one to approach the lesion from one direction, thereby maintaining a single field. It is also attributed to require decreased frontal-lobe retraction and therefore has a lower risk of contusions, cerebral edema, and long-term neurological defects.55 The osteotomy size is smaller than the traditional frontal craniotomy approach, which reduces the risk of dural tears or cerebrospinal fluid leaks58 (Fig. 42.6).

Outcomes, prognosis, and complications

The recurrence rate of nasal dermoids after surgical excision is 12%.61 A meta-analysis showed that the rate of complications with the traditional craniofacial approach was 30% while the subcranial approach reduced the complication rate to 16%.57 Complications included tension pneumocephalus, cerebrospinal fluid leakage, subdural hematoma, longer operative times, and longer intensive care unit stays.58,59

Intradural dermoids and dermal sinus tracts

Basic science/disease process

The incomplete sequestration of neuroectoderm and somatic ectoderm during embryogenesis can lead to persistent dermal sinus tracts from the occiput to the sacrum.62,63 About 1% of these tracts are found in the cervical spine, 10% in the thoracic spine, 41% in the lumbar spine, and 35% in the lumbosacral spine.64 These sinus tracts are cephalically oriented, lined with stratified epithelium, and may lead to the vertebral column, ending as intradural dermoid cysts.62

Diagnosis/patient presentation

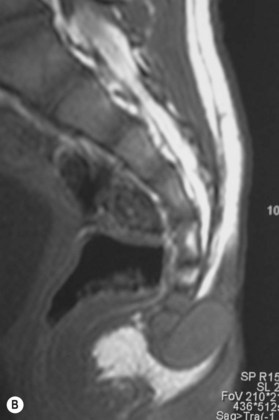

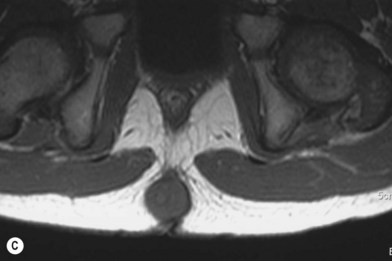

Dermal sinus tracts can present as hypertrichosis, skin tags, abnormal pigmentation, subcutaneous lipomas, or angiomata.65,66 The presence of these tracts can also lead to recurrent bacterial meningitis. Additionally, traction on the spinal cord can occur and can lead to symptoms of motor weakness, autonomic irritation, or sphincter dysfunction. MRI is the imaging tool of choice, and helps with the evaluation of other associated pathologies such as inclusion tumors, dermoids, epidermoids, teratomas,67–74 split cord malformations75,76 and tethered cords77 (Fig. 42.7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree