Chapter 27 Panniculectomy in patients with super obesity

• Strict indication for patient selection according to the Igwe Grades 4–5.

• Panniculectomy should be considered as a combined procedure together with the bariatric surgeon.

• Use patient lifts for assistance.

• Minimal undermining to prevent dead space and seroma.

• No muscle plication in order not to increase intraabdominal pressure.

• Perioperative management should comprise forced diuresis and early ambulation.

Introduction

There are numerous conservative and operative strategies for the treatment of obesity. Plastic surgeons are increasingly confronted with the need for body contouring after massive weight loss through dietetic methods or bariatric surgery.1–5

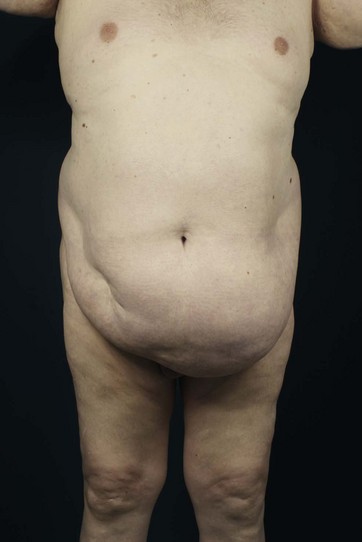

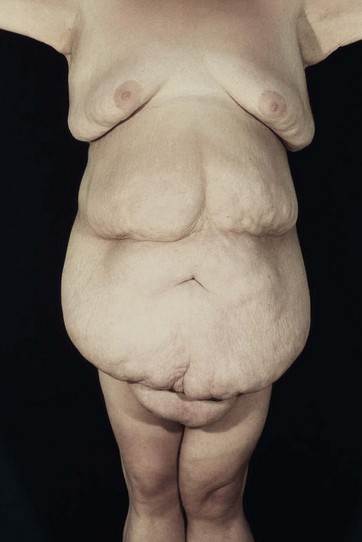

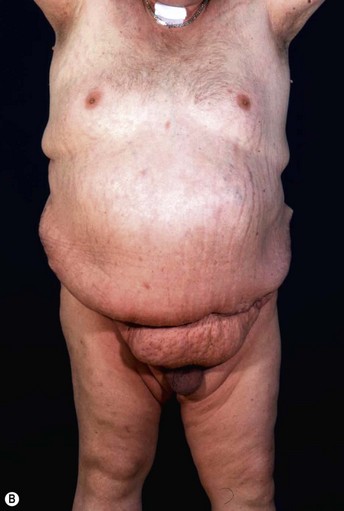

Patients with marked pannus usually have, in addition to significant medical comorbidities such as metabolic syndrome and premature arthritis, massive problems of hygiene in the lower abdominal fold, with recurrent furuncles, abscesses, and fistulas. In addition, distinct functional problems exist such as immobility, with the development of secondary lymphedema, chronic ulceration on the extremities, and pressure sores. Some patients with high body mass index show severe elephantiasis in the entire abdominal wall. Quite often there are additional problems in micturition, especially in male patients whose genitalia are completely obstructed6 (Fig. 27.1).

Historically, panniculectomy was done only in selected cases, when there was complete immobility, or patients were not suitable for bariatric surgery. The aim of such intervention was to interrupt the vicious circle of lack of mobility and insufficient calorie consumption. This was usually followed by a successful conservative weight reduction or bariatric surgery.11–15

Today, such procedures are often performed together with bariatric surgery.5–7 The plastic surgeon performs the panniculectomy, thus the general surgeon gains access to the abdominal wall and then laparoscopically places the gastric banding or performs a gastric bypass or sleeve.

The subsequent weight loss leads to an immediate increase in mobility. If the process of losing weight is completed and there is weight maintenance of about 1 year, subsequent plastic-reconstructive surgical operations are possible to complete the surgical treatment.8

Preoperative Preparation

Patients eligible for panniculectomy should be chosen carefully. Operations on such a patient population are always risky, since metabolic syndrome and the long-lasting cardiovascular stress tend to result in severe complications. Besides the increased general risks, however, there exist significantly increased surgical complication rates, with increased blood loss, excessive seroma formation, wound healing problems and necrosis. In the few publications related to this issue, complication rates are more than 50%; even serious events stated to be 2.5% seem not be substantially increased. Blood loss is given in the literature as significant (from 800 to 2500 ml with decrease of hemoglobin and a consequent transfusion requirement in more than 20%). Hernias were found in about 20% of patients and were treated mostly within the same session. The infection rate given in the literature is on average about 15%, due to poor preoperative hygiene.9–11

Regarding the case history it is important to find out how many serious attempts to diet have been undertaken and whether there are exclusion criteria for bariatric surgery. The normal course of the survey includes, first of all, a classification of the pannus in the degree classification according to Igwe:12

• Grade one: coverage of the pubic hair (Fig. 27.2)

• Grade two: coverage of the mons pubis (Fig. 27.3)

• Grade three: coverage of the upper third of the thigh (Fig. 27.4)

• Grade four: coverage of the top half of the thigh (Fig. 27.5)

In addition to this classification the presence of a permanent lymphedema of the abdominal wall (elephantiasis) needs to be documented. In this case it is called a pannus morbidus and recurrence after abdominal amputation in later courses of surgery is almost certain (Fig. 27.7).

Furthermore, we look for secondary lymphedema in the extremities; carefully inspecting the abdominal fold, the umbilical region, and the external genitalia, especially for intertriginous inflammation, boils, or abscesses. The abdomen is carefully examined in the supine and standing positions for clinical hernia. In particular, the umbilical region is a predilection site. An exploratory ultrasound of the abdomen should be mandatory, because the clinical examination is often difficult. In most cases, we also request a CT scan of the entire abdomen for safe exclusion of a hernia, and a Doppler ultrasound of the deep venous system for the safe exclusion of thrombosis.13