Palatal Fistula

Gregory D. Pearson

DEFINITION

A fistula is defined as an epithelialized tract between two cavities that are not meant to be communicating.

A palatal fistula is an abnormal communication between the oral and nasal cavities.

Palatal fistula can be intentional or unintentional.

Intentional fistulas are fistulas not repaired at the time of initial operation. Examples include:

The alveolar cleft with a Veau III or Veau IV (unless the surgeon elects to perform a gingivoperiosteoplasty)

A Veau IV with a “locked out” premaxilla

These fistulas are unwanted and not planned for during the initial operation.

Veau IV clefts are associated with the highest fistula rate.

No difference in risk for palatal fistula related to gender, age at time of repair, and race.

The difference in fistula rate between straight line repairs and Furlow-type repairs appears to be surgeon/institution dependent with no clear lower risk between the two types of repair.

Palatal fistula repair can be an extremely challenging problem to solve and prevention is the best option.

ANATOMY

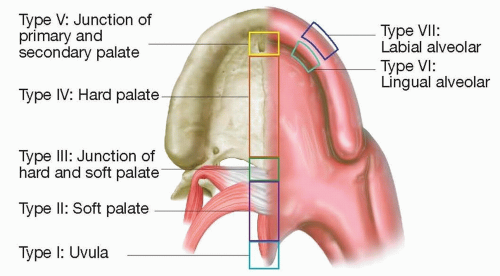

The Pittsburgh fistula classification system classifies fistulas as I to VII, from a posterior to anterior location on the palate4 (FIG 1).

Type I involves only the uvula (consisting of a bifid uvula).

Type II involves the soft palate.

Type III occurs at the junction of the hard/soft palate.

Type IV arises within the hard palate.

Type V is located at the incisive foramen (reserved for Veau IV clefts).

Type VI is a lingual alveolar communication on the alveolus.

Type VII is located on the labial side of the alveolus.

PATHOGENESIS

Several factors have been associated with the prevention of palatal fistula:

Tension-free and watertight closure

Relaxing incisions advocated by von Langenbeck for tension-free closure.

Jackson et al. proposed “CHOP modification” of Furlow palatoplasty for soft palate repair.2

Complete two-layer closure of nasal and oral flaps

LaRossa promoted liberal use of vomer flaps for closure of the nasal floor.5

Infection prevention

The use of perioperative antibiotics is debated in the literature.

NATURAL HISTORY

Palatal fistula will remain patent until the time of closure.

A fistula can be symptomatic or asymptomatic

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Palatal fistula can occur after cleft palate repair, oncologic resection, trauma, or illicit drug use.

Patients may report that the fistula is symptomatic.

Nasal escape of food or liquids

May be intermittent

Typically, viscous liquids like yogurt

Nasal escape of air

May be noted by patient as change in voice

May be noted by speech pathologist as nasal turbulence or hypernasality

Physical examination will demonstrate a hole or communication from the oral to nasal cavity.

Fistulas can range from small to large and vary in location on the palate.

Small fistulas can be difficult to see, but the patient can typically state/point to the location.

An examination under anesthesia with a lacrimal probe can be useful to determine the location, size, and orientation of a fistula.

A dental mirror can be useful in evaluating anterior fistulas.

Deep crevasses or folds of mucoperiosteal tissue can simulate a fistula.

Palatal expansion may open an occult fistula that was already present.

IMAGING

Radiographic fistulograms (such as those performed for an enterocutaneous fistula evaluation) are not necessary.

Physical examination should determine whether a fistula is present.

Nasopharyngoscopy or video fluoroscopy should be employed to determine velopharyngeal gap size in patients with fistula and velopharyngeal dysfunction.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Hypernasality from velopharyngeal dysfunction (VPD)

Nasal escape of liquids/food secondary to poor oral motor planning/retrograde oronasal reflux

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

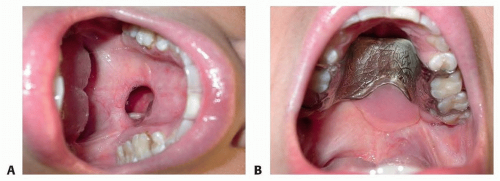

Obturators/dental retainers can be fabricated by dentists or orthodontists to provide symptomatic relief (FIG 2).

Obtaining patient compliance for wearing the retainer can be difficult.

The dental brackets on the retainer may loosen and require retightening or fabrication of a new splint.

The patient must have enough teeth to properly support a retainer.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical management and operative options are largely dictated by the location of the palatal fistula based upon the Pittsburgh classification system.

When determining whether to repair a fistula, the surgeon should strongly consider and assess whether the fistula is symptomatic.

Nasal escape of fluids or foods, hypernasality, and preventing further surgical or orthodontic interventions (eg, bone grafting or orthognathic surgery) are all reasons for attempted fistula repair.

Pittsburgh type I

Bifid uvula rate ranges from 1.34% to 19% of selected populations, but the true fistula rate is probably underestimated in the literature.

Because these fistulas tend to be asymptomatic as well as concerns about anesthesia on pediatric brain development, these fistulas are the least likely to be repaired as a primary objective for an operation.

Pittsburgh type II

When determining the type of reconstruction choice for a soft palatal fistula repair, a surgeon should also make a determination related to a child’s resonance (specifically if VPD is present) and the type of previous repair performed.

If the child has VPD, the fistula may be fixed but hypernasality will likely persist unless addressed with the repair.

If a child has normal resonance regardless of the type of primary palatoplasty performed, augmentation/reinforcement with acellular dermal matrix (ADM) can be used.6

For patients with a fistula after straight-line repair and concurrent VPD, addressing the VPD with either a palatal lengthening procedure or VPD surgery should be strongly considered.

A conversion to a Furlow double opposing Z-plasty typically allows repair of a type II fistula while addressing VPD in children with small velopharyngeal gaps on imaging.7

The CHOP modification with bilateral relaxing incisions can facilitate tension-free closure.

For larger velopharyngeal gaps and fistula or very large fistula (dehiscence), a superiorly based posterior pharyngeal flap may be necessary as conversion to Furlow may not lengthen the palatal sufficiently.

Pittsburgh type III

Traditional teaching reports that the junction of the hard palate and soft palate remains the most common site of fistula, particularly when employing a Furlow palatoplasty.

As for type II fistula, the patient’s resonance and type of previous repair should influence the operation considered for fistula repair.

Pittsburgh type IV

There is significant overlap for techniques used to repair type III and IV palatal fistulas.

The mucoperiosteal flaps tend to scar, become stiffer, and have less mobility compared to flaps used in a primary palatoplasty, thus limiting their advancement or rotation potential.

Pittsburgh type V

This is the second most common location of fistula as well as the most challenging to repair given the relative lack of palatal tissue in this area.

These fistulas are often the result of either poor inset of the lateral palatal mucoperiosteal flaps into the premaxillary segment or more commonly a premaxillary segment that is so anteriorly displaced out of the arch (a “locked out” premaxilla and intentional fistula) that closure at the time of initial palatoplasty is not possible.

Pittsburgh type VI and VII fistulas pertain to the alveolar arch and labial sulcus and are addressed in the chapter on alveolar cleft repair.

Preoperative Planning

The surgeon must discuss the possibility of palatal fistula recurrence after attempted closure with the patient and family.

Assuring proper patient compliance with postoperative instructions prior to embarking upon repair is imperative.

Depending on the type of repair technique used, a surgeon may consider having orthodontist fashion of a postsurgical retainer to protect repair while healing, particularly for type IV and V fistulas.

It is important to ensure the retainer does not put pressure on flaps or area of repair while still protecting the surgical site from tongue and food particulate.

As previously stated, in rare instances, an examination under anesthesia with a lacrimal probe can be useful to determine the location, size, and orientation of a fistula.

If a local flap is used, it must be protected from masticatory trauma during healing.

Positioning

The patient should be orally intubated.

May use a regular endotracheal tube or oral RAE endotracheal tube depending upon surgeon and anesthesiologist’s preferences.

The endotracheal tube may be positioned in the midline or laterally depending on the repair technique chosen.

Typically, the patient should be placed in a horseshoe headrest with a shoulder roll and slight extension of the neck.

A Dingman mouth prop or dental bite blocks (in which use depends on surgical technique to be employed) can be extremely useful for proper exposure of the intraoral cavity.

Approach

Although multiple strategies can be performed for each site, the most common/useful approaches will be addressed according to the Pittsburgh classification system.

Pittsburgh type I: Excision and reapproximation

Pittsburgh type II:

Lateral relaxing incisions and rerepair

May consider augmentation with ADM

Conversion by Furlow palatoplasty

Posterior pharyngeal flap

Pittsburgh type III:

Lateral relaxing incisions and rerepair

May consider augmentation with ADM

Posterior pharyngeal flap (if VPD present)

Buccal myomucosal flap

Facial artery musculomucosal (FAMM) flap

Pittsburgh type IV:

Lateral relaxing incisions and rerepair with pushback technique

May consider augmentation with ADM

Elevation of mucoperiosteal flaps and pushback technique

Labial mucosal flap

If space in dental arch to pass through or if bite blocks employed

Buccal myomucosal flap

FAMM flap

Tongue flap

Free tissue transfer

Pittsburgh type V:

Labial mucosal flap

FAMM flap

Tongue flap

Premaxillary turnover flap

Primarily used as nasal lining flap for fistula at anterior incisive foramen in Veau IV cleft

Free tissue transfer

TECHNIQUES

▪ Excision and Reapproximation

Midline oral endotracheal tube placement; head placed in headrest with slight extension.

Perform proper surgical time-out.

Place Dingman mouth prop.

Prep and drape the patient.

Mark out medial epithelialized areas that must be excised.

Inject with local anesthesia of choice. Author prefers ¼% Marcaine with 1:200 000 epinephrine.

Excise medial portions of fistula.

Repair with resorbable sutures. Author prefers 4-0 chromic sutures.

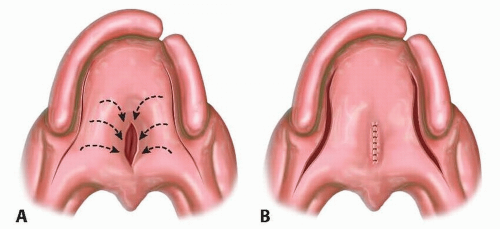

▪ Lateral Relaxing Incisions and Rerepair (TECH FIG 1)

Preparation for All Fistula Types

Midline oral endotracheal tube placement; head placed in headrest with slight extension.

Perform proper surgical time-out.

Place Dingman mouth prop.

Prep and drape the patient.

Mark out lateral relaxing incisions (von Langenbeck style relaxing incision on the hard palate, soft palate, or both depending upon fistula type).

Relaxing incisions typically need to be longer than initially thought due to relative immobility of soft tissues.

Inject with local anesthesia of choice. Author prefers ¼% Marcaine with 1:200 000 epinephrine.

Pittsburgh Type II Fistula

Incise lateral relaxing incisions on the soft palate.

Incise medial fistula.

Separate nasal mucosa from levator muscles with sharp dissecting scissors.

Separate oral mucosa from levator muscles with sharp dissecting scissors.

TECH FIG 1 • A. Lateral relaxing incisions. B. Rerepair.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access