Chapter 73 Osteoporosis After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction?

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries and their Treatment

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are usually sustained by a young and active population, often under heavy pressure to continue heavy labor or sports activities at a competitive or recreational level. The natural history of an ACL injury still remains unclear. Conservative (nonsurgical) treatment has been reported to produce unsatisfactory results, such as chronic instability, muscle weakness, and osteoarthritis (OA), but also to render acceptable function for some patients.1 It is a common algorithm that surgical intervention is recommended if the patient requests a return to high-risk pivoting sports or if symptoms of giving way are persistent after a conservative program. To our knowledge, however, this has not been scientifically proven in randomized controlled studies.

Peak Bone Mass and Natural Bone Losses

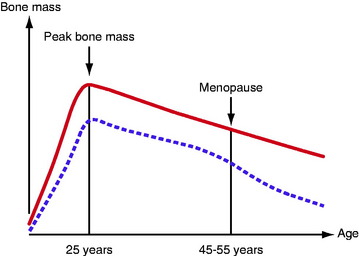

We start adult life with a peak bone mass, 80% of which is determined by genetic factors. This is also the case for fat and muscle tissue, 65% to 80% of which are genetically determined. Men have a higher peak bone mass than women (Fig. 73-1). During childhood and adolescence, it is possible to increase bone mass with sufficient nutrition and physical activity. However, the positive effect of training during childhood and adolescence appears to be lost with the cessation of a sporting career.2

From the peak bone mass at the age of 25 years, there is an annual loss of approximately 0.5% to 1%. The loss for women is accelerated in connection with menopause and, during the subsequent 10 years, the annual loss is as much as 2% to 4% (see Fig. 73-1). The bone metabolism turnover rate is 4 to 10 times higher in trabecular bone compared with cortical bone. The content of trabecular bone in the calcaneus is 95%; in the lumbar vertebrae, 40%; and in the neck of the femur, 40%. In a period of 8 years, the bone tissue is completely replaced. The potential as an adult to compensate for a low peak bone mass or significantly to increase bone mass by strenuous exercise or an excessive intake of calcium/vitamin D appears to be virtually nonexistent. However, the female athlete triad, a disorder in young females characterized by eating disturbances, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis, could be an exception. For these individuals, there is still the potential for “catch-up” in bone mass in the third decade of life if the condition is reversed. The normal physiological bone loss seen during pregnancy and breastfeeding also appears to be reversible.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis and its consequences, with an increasing fracture incidence among the aging population in Western countries, have become a challenge to general public health and the welfare system. There are many known risk factors for osteoporosis and/or fractures. They can be divided into (1) nontreatable risk factors such as older age, previous fracture, female gender, menopausal age, heredity, ethnicity, and body height and (2) treatable risk factors such as physical inactivity, low body weight/low body mass index (BMI), cortisone treatment, low bone density, tendency to fall, tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, low exposure to sunlight, impaired vision, and calcium and vitamin D deficiency.3 Older age and a history of previous fractures are regarded as by far most important risk factors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree