Oral Cavity and Pharynx

Introduction

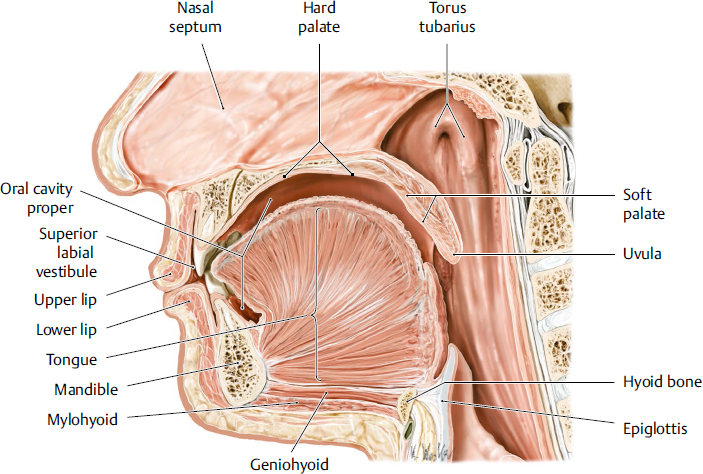

The oral cavity is the entrance of the upper digestive tract, continuing into the oropharynx; it is divided into two regions (Fig. 20.1). The first region is the oral vestibule, located external to the dental arch. The second region is the oral cavity proper, located internal to the dental arch. The components of the oral cavity include the upper and lower lip mucosa, teeth and gingiva, alveolar mucosa, buccal mucosa, tongue, hard and soft palate, floor of the mouth, and uvula. The palate is the roof of the mouth and separates the oral and nasal cavities. The pharynx is located at the posterior aspect of the oropharyngeal isthmus. Two important functions involving the oral cavity and pharynx are mastication and swallowing. Multiple muscles work together to send a bolus of food to the esophagus. Other major functions are occlusion and aesthetics. The oral cavity and pharynx contain an abundant supply of blood vessels and nerves in a constricted space, providing a particular challenge for clinicians undertaking surgical procedures. In this chapter, we explain the details of the clinical anatomy of oral cavity and pharynx to promote better understanding for clinical practice.

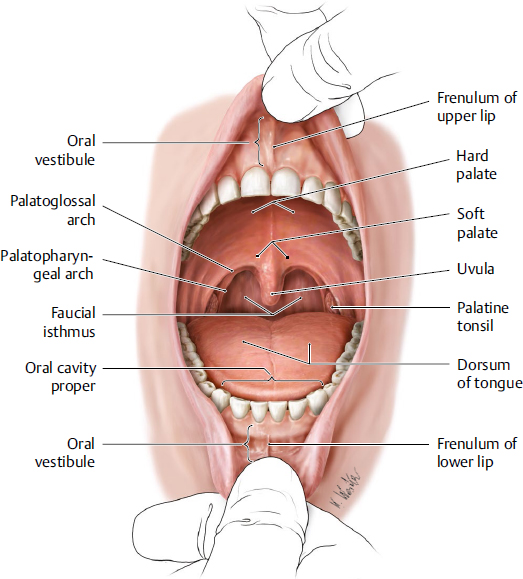

Oral Vestibule

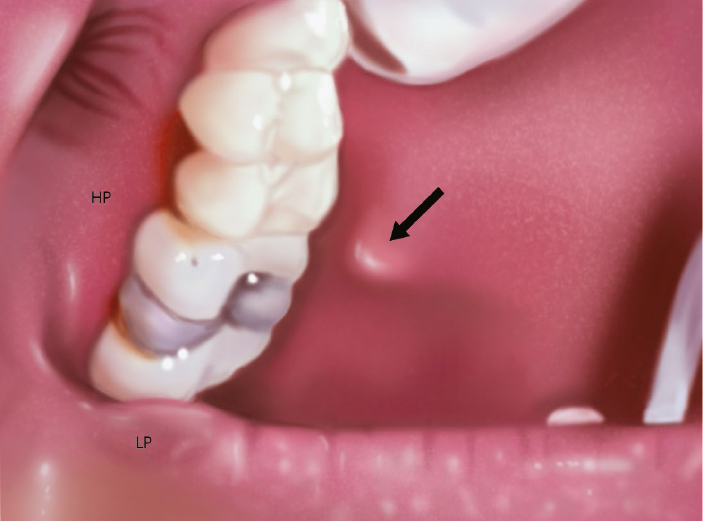

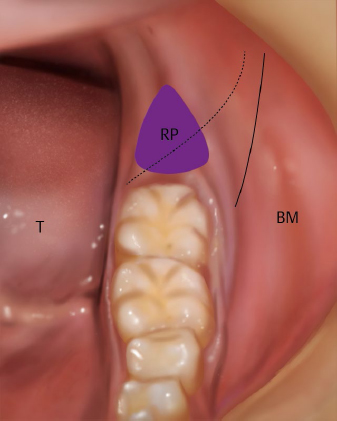

The oral vestibule is the region surrounded by the lip (buccal) mucosa, mucobuccal fold, alveolar mucosa, gingiva, and upper and lower dental arches. Its shape in the axial plane is that of a horseshoe, and it is separated from the oral cavity proper when the upper and lower teeth are in occlusion. Mucosal folds that run from the central incisor region of the alveolar mucosa to the lip mucosa are the frenulum of the upper and lower lips (Fig. 20.2). Mucosal folds that run from the molar region of the alveolar mucosa to the buccal mucosa are called buccal frenula. The parotid duct runs from the parotid gland, passes in front of the masseter muscle, enters into the buccal fat pad, and then reaches the parotid papilla located in the buccal mucosa (Fig. 20.3). A small triangle (the retromolar triangle) lies just behind the most distal molar and a small ridge in the retromolar region (the retromolar pad) (Fig. 20.4). The lingual nerve branches off the mandibular nerve and occasionally crosses over the retromolar triangle.1 The external oblique ridge, which begins lateral to the retromolar pad, continues on to the anterior border of the ramus. When the mandible opens and closes, or when the lips suck, the bone movement and muscle contraction change the form of the oral vestibule. The lower part of the oral vestibule in particular is affected by the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle, masseter muscle, buccinator muscle, orbicularis oris muscle, mentalis muscle, and coronoid process; the upper part is affected by the orbicularis oris muscle, buccinator muscle, medial pterygoid muscle, levator anguli oris muscle, nasal muscle, depressor septi muscle, and infrazygomatic crest. If the superior labial frenulum is located in a high position on the gingiva, the right and left maxillary incisor teeth may exhibit a median diastema, and frenoplasty is often required.

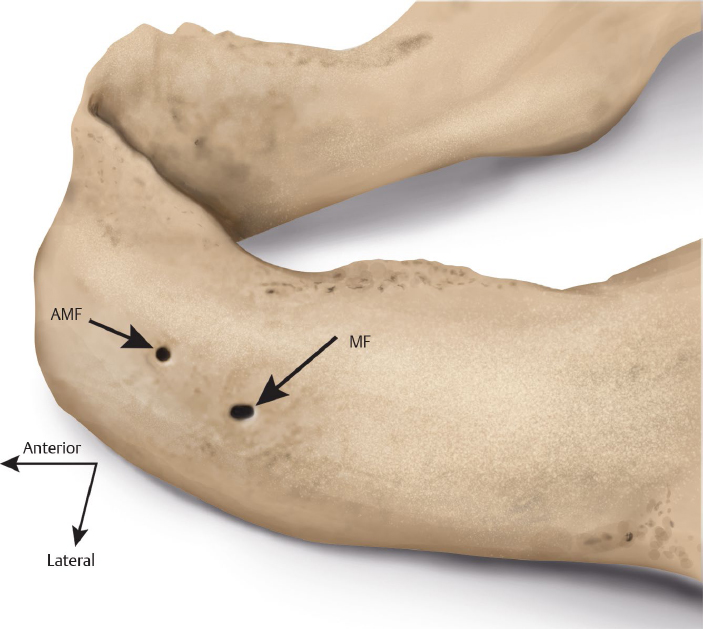

The orbicularis oris muscle and buccinator muscle are present beneath the mucous membranes of the labial and buccal mucosae. In the mandible, there are two mental foramina, just inferior to the apex of the second premolars, through which the mental nerves, arteries, and veins emerge. The vertical distance from the margin of the mandible to the mental foramen is reported to be approximately 12 mm.2 Surgical procedures in the premolar region should be undertaken carefully. When teeth are lost, the alveolar bone proper resorbs and the thickness of the mandible decreases, so the mental foramina sometimes open just below the alveolar mucosa; nerves exiting the foramina are then easily compressed by dentures. Recent developments in imaging have revealed that accessory mental foramina exist around the mental foramen in approximately 10% of cases3,4 (Fig. 20.5) and that the accessory mental nerve branches off from these accessory foramina.

Fig. 20.1 Midsagittal plane of the oral cavity and pharynx. (From THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Head and Neuroanatomy. © Thieme 2010, Illustration by Karl Wesker.)

Fig. 20.3 The left parotid papilla (the orifice of the parotid duct) is indicated by the black arrow. HP, Hard palate; LP, lower lip.

Teeth and Periodontal Tissues

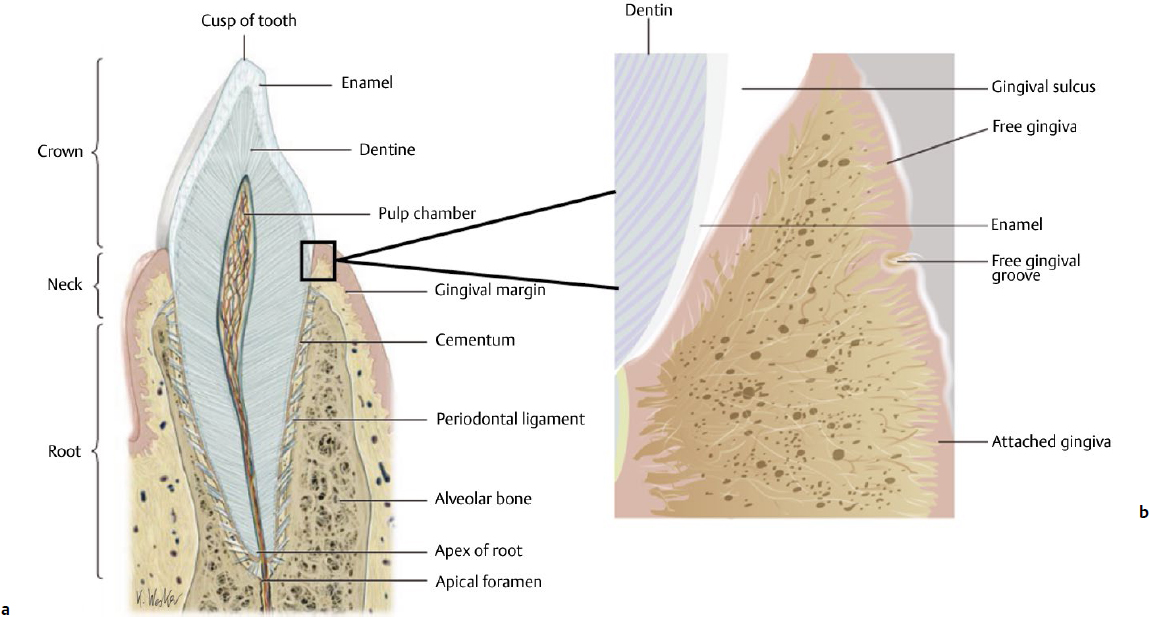

The teeth consist of a crown, the surface of which is covered by enamel, a hard translucent tissue, and the root, which is covered by cementum. Within the crown and root is a layer of dentin surrounding a central pulp cavity. The apical foramen is a hole at the tip of the root, through which the dental pulp, blood vessels, and lymph vessels enter and exit the dental pulp chamber. The root is surrounded by the periodontal ligament (Fig. 20.6). Enamel is the hardest tissue in the human body; at the same time, it is a fragile and breakable tissue. The enamel is approximately 96% inorganic matter called hydroxyapatite; it reaches a maximum thickness of 2.5 mm over the cusps and is quite thin at the cervical margins. After crown formation is complete, no additional enamel forms, but the enamel of young people is easily demineralized and remineralized. Dentin is a yellowish tissue composed of hydroxyapatite (70%), collagen (20%), and water (10%). Dentin is more flexible than enamel, so it acts as a buffer to prevent the enamel from fracturing. Additionally, if inflammation occurs in the dental pulp as a result of dental caries or traumatic injury after the start of occlusal function, secondary dentin will form inside the dentin. The cementum covers the surface of the dentin of the root and is covered by the periodontal ligament, which consists of fibrous connective tissue that is 0.15 to 0.38 mm thick. Sharpey’s fibers, which emerge from the cementum, penetrate the periodontal ligament and enter the alveolar bone. The main roles of the periodontal ligament are to support the teeth, control sensitivity, and provide a blood supply. The activity of the periodontal ligament and the number of fibers it contains decrease with age. Dental pulp is a soft tissue that includes blood vessels, nerve fibers, lymph vessels, and connective tissue. It is divided into two parts, the coronal pulp and the radicular pulp, which communicate at the cervical region. The radicular pulp of anterior teeth is single; but for posterior teeth, there are multiple areas of radicular pulp. Both coronal pulp and radicular pulp become thinner as dentin deposition continues with aging. The apical foramen becomes narrower because of deposition of cementum.

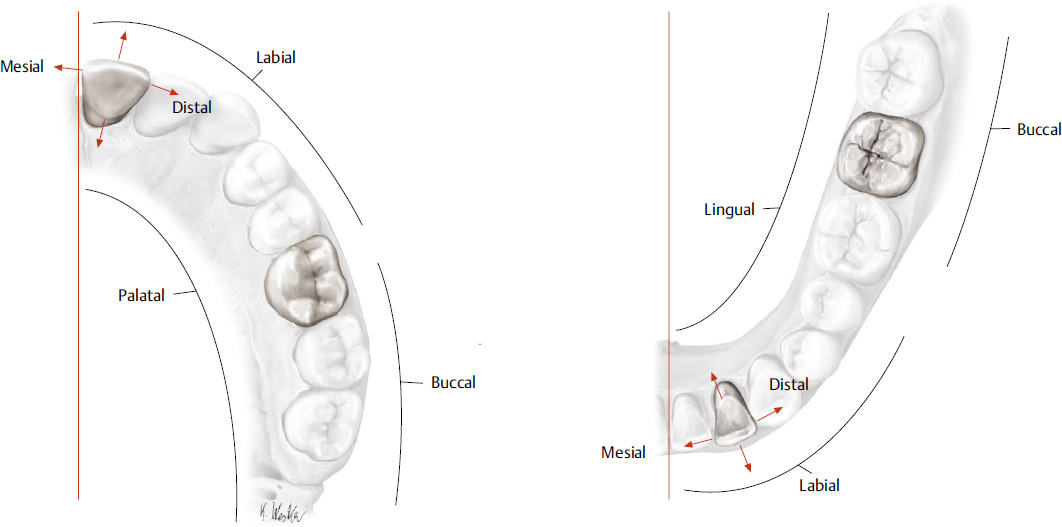

The number of human adult permanent teeth is 32, and these are each surrounded by alveolar bone. Alveolar bone is divided into two parts: alveolar bone proper, which is adjacent to the cementum, and supporting bone. The alveolar bone proper resorbs along with the loss of teeth. There are eight kinds of permanent teeth: central incisor, lateral incisor, canine, first premolar, second premolar, first molar, second molar, and third molar (wisdom teeth) from the midline to posterolateral. The mesial and distal tooth surfaces are those closest to and farthest from the midline, respectively. The term labial is used for incisors and canine teeth, and buccal is used for premolar and molar teeth. Palatal denotes the inside surface of maxillary teeth, and lingual denotes the inside surface of mandibular teeth (Fig. 20.7). These designations are used to describe the precise location of small carious lesions. The deciduous teeth total 20, and they are called deciduous central incisor, deciduous lateral incisor, deciduous canine, first deciduous molar, and second deciduous molar from median to posterolateral. Deciduous teeth begin to erupt 6 to 8 months after birth. The deciduous central incisor erupts first, and the deciduous dentition finishes erupting at approximately 2 years of age. Then deciduous teeth begin to be replaced by permanent teeth at age 6 to 7 years. The permanent dentition is complete by the age of 13, except for the third molar, for which the age of eruption differs between individuals. The upper teeth are innervated by three superior nerves arising from the maxillary nerve: the posterior superior alveolar nerve, the middle superior alveolar nerve, and the anterior superior alveolar nerve. The lower teeth are innervated by the inferior alveolar nerve arising from the mandibular nerve. Both the upper and lower teeth are supplied by branches of the maxillary artery. The upper teeth are supplied by the anterior, middle, and posterior superior alveolar arteries, and the lower teeth are supplied by the inferior alveolar artery. The veins accompanying the maxillary artery drain the upper and lower jaw into the pterygoid venous plexus and collect the maxillary vein, deep facial vein, and buccal vein and then drain into the retromandibular vein and facial vein.

Fig. 20.7 Designation of surfaces of the teeth. (a) Inferior view of the maxillary teeth. (b) Superior view of the mandibular teeth. (Modified from THIEME Head and Neck Anatomy for Dental Medicine. © Thieme 2010, Illustrations by Karl Wesker.)

Gingiva/Alveolar Mucosa

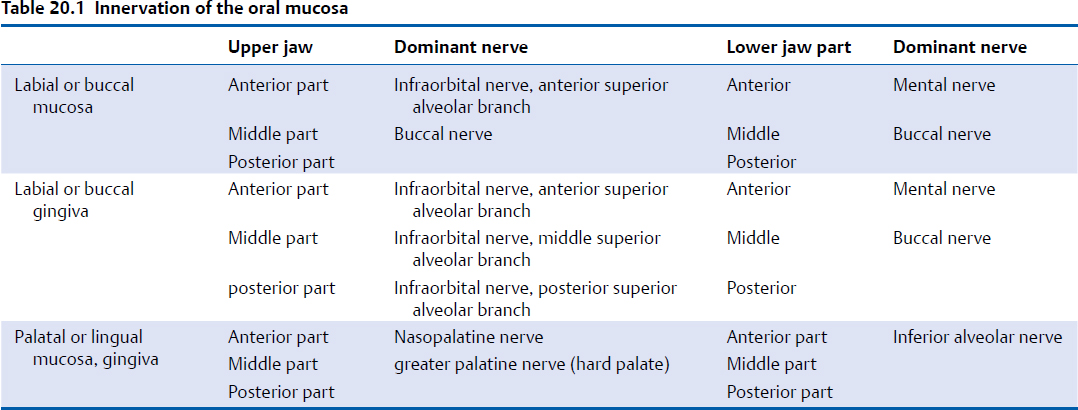

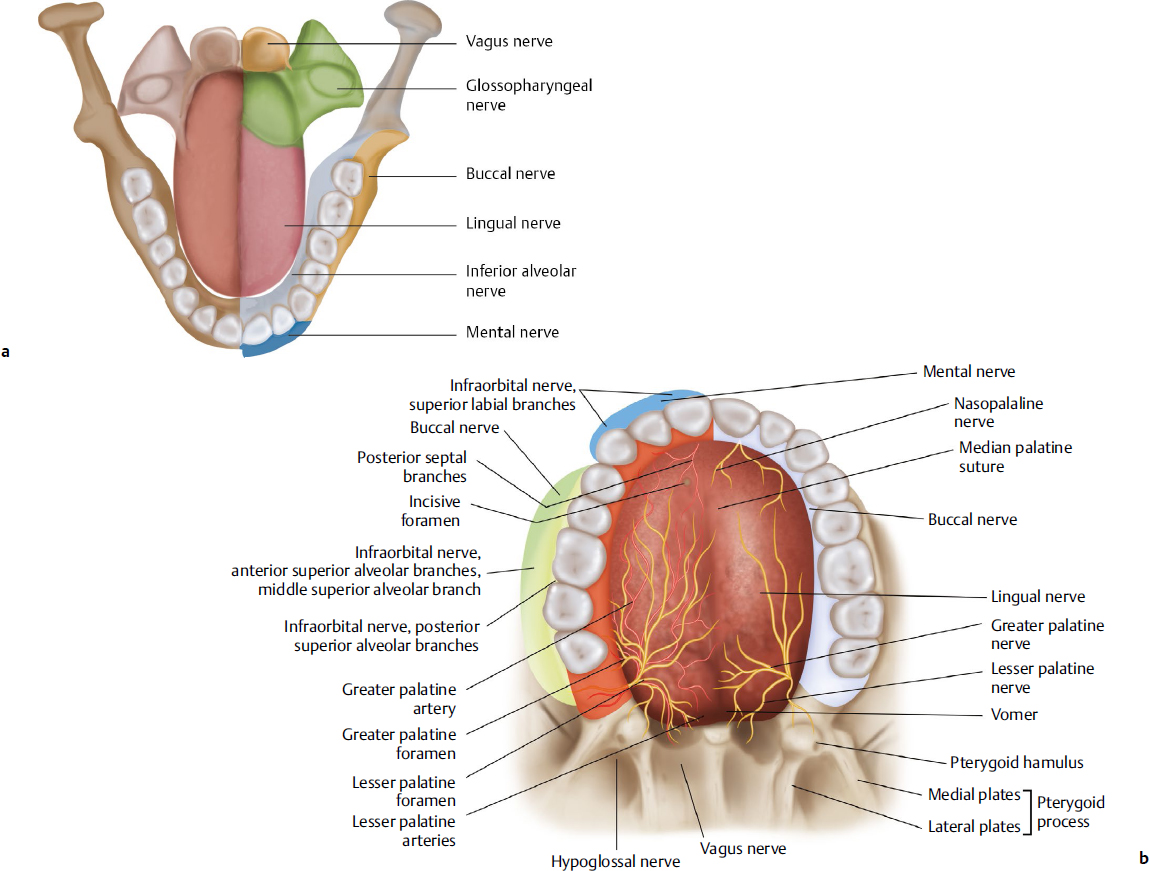

The immobile and keratinized mucosa that surrounds the alveolar bone and coheres to the periosteum is called gingiva (Table 20.1). The mobile mucosa between the gingiva and the gingivobuccal fold is known as the alveolar mucosa and is not normally keratinized. The gingiva is further subdivided into free gingiva and attached gingiva by the free gingival groove (Fig. 20.6). Innervation of the lower gingiva and alveolar mucosa comes from the lingual, buccal, and mental nerves; innervation of the upper gingiva and alveolar mucosa comes from the nasopalatine, greater palatine, and buccal nerves (Fig. 20.8a,b).

Palate

The hard palate forms the roof of the oral cavity and is lined by bone (Fig. 20.8b, Table 20.1). The posterior soft part of the palate lacks bone, is called the soft palate, and consists of striated muscles. The border between the hard and soft palates is easy to visualize by having the patient say “Ah”; then only the soft palate vibrates. The posterior end of the soft palate is the palatine velum, in the middle of which the uvula hangs. The bony palate is formed by the maxillary bone in its anterior two-thirds and by the palatine bone in its posterior one-third. On the surface of the palatine mucosa are incisive papilla, transverse palatine folds, palatine raphe, and palatine foveolae. The mucosa of the hard palate is composed of the epithelium, proper lamina and submucosal tissue. The epithelium is keratinized, and the proper lamina is thick and filled with connective tissue in the anterior part of the hard palate. The submucosal tissue of the incisive papilla and the transverse palatine folds are filled with fat tissue, but the palatine raphe lacks submucosal tissue. If the palatine torus exists, the palatine mucosa is so thin that it is easily injured and may form ulcers caused by physical and chemical damage. Palatine glands are present at the posterior surface of the soft palate. Many taste buds are also located in the soft palate. The incisive fossa is just under the incisive papilla and ascends to the incisive canal. The nasopalatine artery, vein, and nerve run through the incisive canal; so care needs to be taken when incising over the incisive papilla. The greater palatine foramen is located 15 mm lateral to the palatine raphe, between the second and third molar. The greater palatine artery and nerve run to the anterior part of the hard palate from the greater palatine foramen, so it is risky to incise the palate transversely. Many clinicians have reported cases in which repair of an oroantral fistula was undertaken using the palatine mucosa for the axial pattern flap and using the greater palatine artery as a feeding vessel.5 The muscles that form the soft palate are described in the section on swallowing.

Tongue

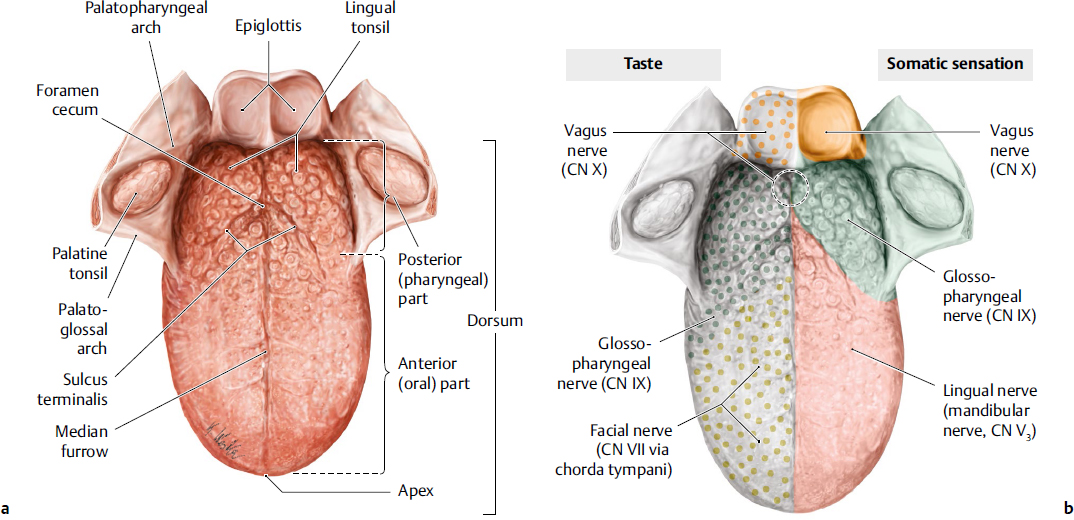

The tongue is a muscular organ, arising from the oral floor and spreading into the oral cavity proper (Fig. 20.9). The intrinsic muscles change the shape of the tongue, and the extrinsic muscles move the tongue and intersect and play important roles in mastication, swallowing, and speech. In addition, one of the most important functions of the tongue is as a taste receptor. Three cranial nerves convey the taste fibers: CN VII (facial nerve, chorda tympani branch), CN IX (glossopharyngeal nerve), and CN X (vagus nerve). Thus, a disturbance in taste sensation involving the anterior two-thirds of the tongue indicates the presence of a facial nerve (chorda tympani) lesion, whereas a disturbance of somatic sensation indicates a lingual nerve lesion.

Fig. 20.9 (a) Surface anatomy of the lingual mucosa. (b) Soma tosensory innervation (left side) and taste innervation (right side) of the tongue. (Modified from THIEME Head and Neck Anatomy for Dental Medicine. © Thieme 2010, Illustrations by Karl Wesker.)

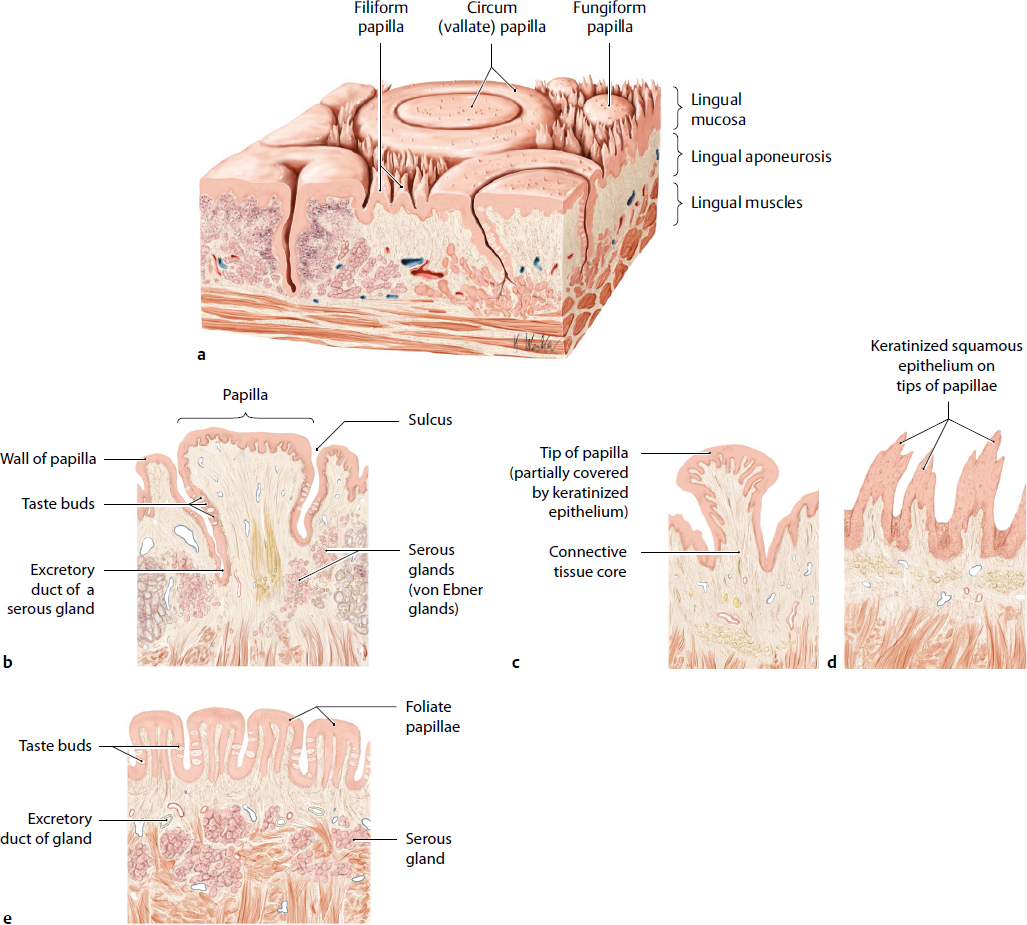

On the dorsal mucosa of the tongue are four kinds of papillae: filiform papillae, fungiform papillae, foliate papillae, and circumvallate papillae (Fig. 20.10). Filiform papillae are the smallest and are distributed over the whole anterior two-thirds of the tongue; they are the only papillae that have no taste buds. They are keratinized and white. Fungiform papillae exist predominantly at the lingual apex and sometimes have taste buds. They are not keratinized, so they take on the red color of the capillary vessels. Foliate papillae are the four to seven folds located on the posterolateral region of the tongue. In adults, the taste buds in the foliate papillae degenerate. Serous glands lie under the foliate papillae for the purpose of cleaning the taste buds. Approximately 10 circumvallate papillae are positioned in front of the terminal sulcus and form a V-shaped line. They are the largest tongue papillae (3 mm in diameter) and are surrounded by a deep groove in which there are taste buds in the epithelium. In adults, approximately two-thirds of the taste buds are on the tongue. The soft palate also has many taste buds. Innervation of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue comes from the chorda tympani, and the posterior third is innervated by the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. Therefore, it is known that if these nerves are injured by surgical procedures, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy, dysgeusia may occur. It is difficult to examine the root of the tongue when the mouth is open. In cases of ankyloglossia, in which the lingual frenulum is too rigid to allow movement of the tongue and speech is hampered, lingual frenoplasty might be necessary. The deep lingual artery and vein and the lingual nerve are situated on the inferior surface of the tongue, so sensory paralysis and bleeding may occur if they are injured. In particular, care should be taken not to injure the deep lingual vein because of its position directly under the mucosa (Fig. 20.11). If the tongue is extended, the border between the inferior surface of the tongue and the oral floor is hard to see. It is well known that there are communicating branches between the lingual and hypoglossal nerves in the body and apex of tongue; however, their physiologic function is not fully understood.6

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree