Introduction

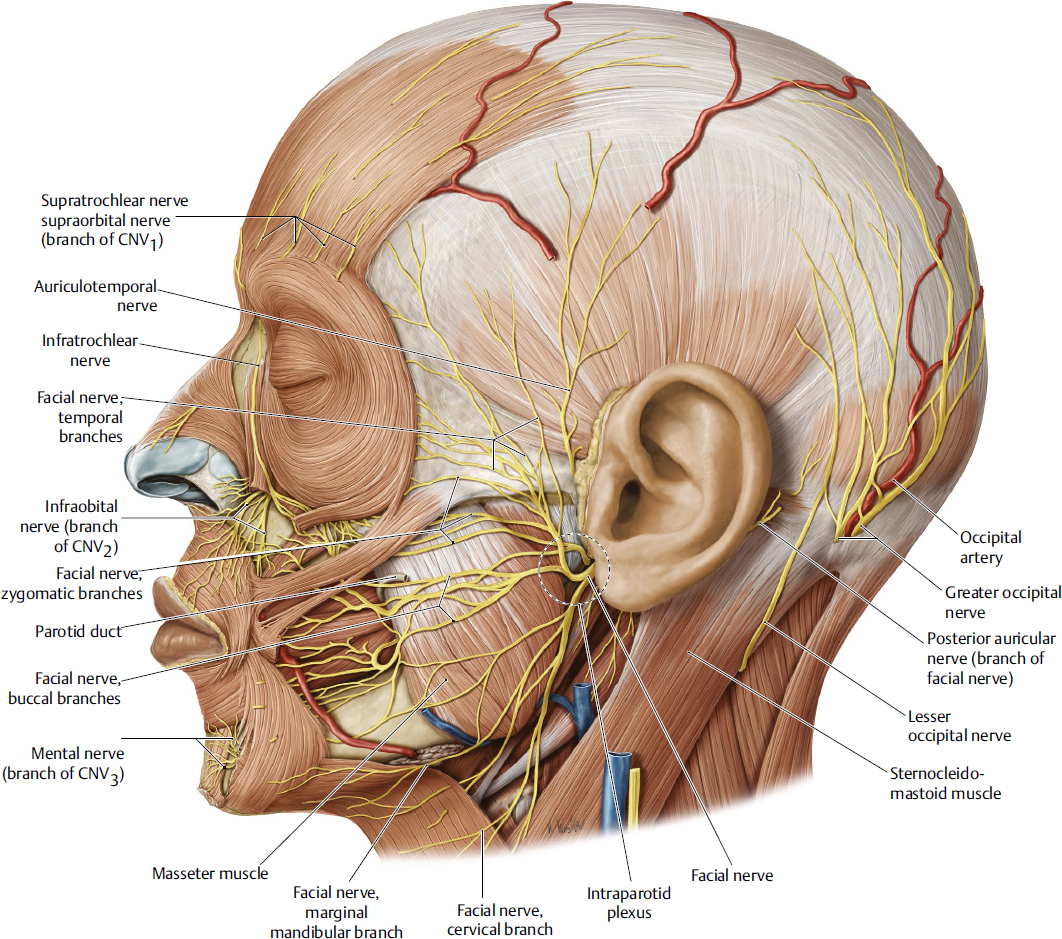

Navigation around the facial nerve is important in any facial procedure, invasive or noninvasive. With the advent of a “less is more” trend in facial aesthetics, attention toward avoidance of the facial nerve has been falsely perpetuated. Less attention to educating medical residents on deeper-plane facelift techniques has developed an “out of sight, out of mind” attitude toward the facial nerve and its branches. Attention is gained when an inadvertent facial nerve injury happens, without the knowledge of how or where it could have occurred. It is hoped that this chapter on facial nerve anatomy will shed light on the anatomical landmarks and fascial boundaries of the nerve, as well as highlight danger zones of facial nerve injury (Fig. 9.1).

Facial nerve injury during facelift surgery is a relatively rare but real occurrence, with an incidence ranging between 0.5 and 2.6%. This risk may be acceptably low in a primary superficial facelift, where the risk of injury to the facial nerve may be considered less, although the actual risk may be the introduction of scarring around the nerve and risk of contorting the nerve position, which makes it prone to injury in a secondary facelift procedure after a superficial facelift has failed. The more superficial facelift techniques have been subjected to longevity issues, although this topic has been subjectively debated. A 2- to 5-year longevity of a superficial lift is well documented. If the continued superficial plane is used, the risk for injury may be with superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS)plication or SMASectomy, although if the deeper plane is entered, scarring may distort the facial nerve branches, making them susceptible to injury. Even injectables can cause enough irritation and scarring whereby care should be taken to maintain the fascial boundaries of the facial nerve during SMAS dissection.

A sub-SMAS dissection is safe, and the facial nerve does have a predictable location, which makes navigating around it easy for the experienced facelift surgeon. There are predictable locations that the nerve is tethered either in fascia or with a neurovascular ligamentous adhesion. These are the areas where caution is warranted when elevating the facelift flap.

Understanding of the facial nerve in three dimensions is beneficial when elevating the SMAS. Knowledge about the cutaneous landmarks, the bony landmarks, and the depth of the nerve as it traverses the face from posterior to anterior makes the ability to alter and customize the SMAS flap to meet each individual’s rejuvenation goals. The thickness of the face and SMAS does vary in different patients, and a thin-faced patient will likely have a thin SMAS flap; therefore, numerical depth is less clinically applicable where anatomical boundaries with fascial planes are more relevant in facelift surgery.

Facial Nerve

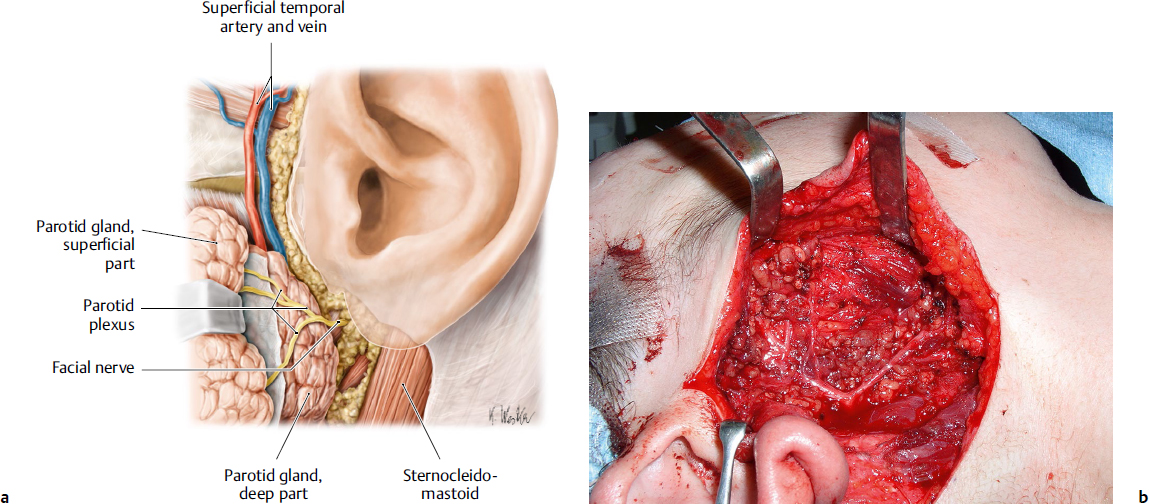

The facial nerve is a motor nerve as it exits through the stylomastoid foramen at the skull base. The main trunk is anterior to the midportion of the earlobe and lies approximately 2 cm below the skin; it is surrounded by dense fascia. The nerve ascends from the stylomastoid foramen into the parotid gland at an approximate 45-degree angle. The main trunk branches within 1 cm of entering the parotid gland as two main trunks superior and inferior. The nerve trunks bifurcate the parotid gland’s two lobes and travel superficial to the deep lobe at a depth of 1 cm (Fig. 9.2a,b). The two main trunks of the facial nerve split into the formal trunks of the named branches of the face as they exit the parotid gland (Fig. 9.2c).

Frontal Branch

The subcutaneous course of the frontal (temporal) branch was initially described in 1966 by Ramos and Pitanguy (Fig. 9.3).1 Their findings of an anatomical study showed that the frontal branch coursed from 0.5 cm from the tragus to 1.5 cm lateral to the supraorbital rim. Their findings have provided a topographic map for the nerve, although its depth in three dimensions continues to be confusing. Numerous studies have described its location, but consensus has not been attained as to the depth or its fascial boundaries.

The fascial relationships of the frontal branch of the facial nerve vary remarkably within the literature. It remains ambiguous in part because of the lack of a standardized nomenclature and in part because of the considerable variation in the described depth of the nerve at various levels across the zygomatic temporal region. As shown by the works of Furnas, Gosain et al, and Stuzin et al, no consistency exists as to the exact fascial plane and safe plane of dissection in and across the zygomatic arch.2–5 Confounding the issue further are the numerous names attributed to the various fascial layers. The temporoparietal fascia, which is a continuation of the SMAS, has multiple names and has been referred to as the superficial temporal fascia and or the galea aponeurotica. The deep temporal fascia envelops the temporalis muscle and extends down to the zygomatic arch, fusing with the periosteum anteriorly and posteriorly. This layer is often broken down into superficial and deep portions, which are separated by the temporal fat pad as described by Stuzin et al.4,5 With regard to the superficial deep temporal fascia, several names exist in the literature and include the intermediate fascia and the innominate fascia.4–6 Finally, there are descriptions of the loose areolar plane between the temporoparietal fascia and the deep temporal fascia, and some authors refer to this area as a separate fascial plane and have referred to it as the innominate fascia or subaponeurotic plane. These variations and discrepancies are partly to blame for the lack of consistency with respect to the depth and location of the frontal branch of the facial nerve across the zygomatic temporal region.

Fig. 9.1 Overview of the facial nerve (left lateral view). (Reproduced from THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Head and Neuroanatomy, © Thieme 2010, Illustration by Karl Wesker.)

The thought that the nerve branch travels within the SMAS has clinically correlated with the alteration of facelift technique. Stuzin et al. describe a lateral low SMAS fasciotomy to protect the frontal branch with a superior extension to the lateral can-thus.7 In the high SAMS technique, the SMAS is incised transversely at a level above the zygomatic arch. The advantage of this technique would be to provide a vertical vector to the face-lift with a composite flap containing SMAS and subcutaneous cheek tissue.8,9 Based on previous studies, one might expect a 100% incidence of frontal branch injury, but in reality the author has not had any permanent nerve injury. The technique to prevent nerve injury in this technique includes a subcutaneous temporal dissection superficial to the frontal branch 2 cm above the arch at the level of the lateral canthus. The nerve is isolated on a temporal mesentery with deep dissection on the deep temporal fascia. After the SMAS has been elevated, the level of SMAS transection is then incised with a push cut across the arch to the orbicularis oculi while maintaining the temporal mesentery.

The high SMAS facelift uses a multiplanar sub-SMAS and subcutaneous dissection to mobilize the cheek and then a transverse SMAS fasciotomy above the zygomatic arch to allow for a vertical vector of repositioning. This direction of facelift replaces the facial soft tissue as a composite unit to a youthful and natural position. The transverse SMAS incision has been one point of contention in gaining acceptance of this procedure secondary to the lack of consensus of the course of the frontal branch and the inherent risk of frontal branch injury. The study by Trussler et al has demonstrated that if the procedure is performed appropriately, the frontal branch is deep to the SMAS above the zygomatic arch and has an additional layer of fascia, the parotid temporal fascia, covering it.10 This fascia was first described in 1965 by Furnas as a laminated areolar tissue continuous with the galea.3 Additional descriptions have included a superficial temporal fascia, temporoparietal fascia, and innominate fascia. I propose that the fascia be named by its origin and insertion, like that of the parotid masseteric fascia and temporaparietal fascia, so that the terminology is uniform in this region. The parotid temporal fascia is not a novel fascia, as demonstrated by previous descriptions, although this term is a plea for consistency so that the course of the frontal branch can be easily related to the fascial boundaries over the zygomatic arch. This study employs both gross dissections under loop magnification as well as histologic evaluation of 1 cm intervals over the arch. The frontal branch of the fascial nerve can be easily identified by its subcutaneous course over from the tragus to the lateral brow. The cutaneous landmarks defined by Pitanguy were confirmed to be accurate in this study,1 although this was not the focus of the study. The frontal branch was identified in all cadaver dissections via a pretragal incision and a sub-SMAS dissection with elevation of the parotid and identification of the zygomatico-frontal trunk of the facial nerve. This trunk was uniformly covered by the investing fascia of the parotid, which then extended superiorly as the parotid temporal fascia where the nerve traveled in a heterogeneous fat pad. The SMAS was easily elevated off this fascia as there was an areolar plane between them. This plane was easily elevated to above the arch, with the SMAS maintaining its integrity; the parotid temporal fascia can be elevated off of the nerve to above the zygomatic arch as demonstrated in the dissection video accompanying this chapter.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree