Oncoplastic Surgery: Segmental Resection for Lumpectomies

Kristine E. Calhoun

Benjamin O. Anderson

Breast conserving therapy was first investigated as a treatment option for women affected by breast cancer beginning in the 1970s, and clinical trials have since demonstrated equivalency in terms of overall survival between lumpectomy plus radiation and mastectomy (1,2). Although there are clear contraindications to lumpectomy, such as widespread multicentric disease and persistently positive surgical margins, for the appropriately selected individual, breast conserving therapy can offer effective treatment and offer the psychological benefit of retention of the breast.

In a typical lumpectomy, the skin is opened, the tumor removed, and the wound closed without any specific effort being made to obliterate the internal resection cavity. Closing the fibroglandular tissue can result in unsightly defects if alignment of the breast tissue is suboptimal. Often times, fibroglandular tissue that is sutured and closed at middle depth in the breast while the patient is supine on the operating table results in a dimpled, irregular appearance when the patient stands up. Given this potential, most surgeons choose to only close the skin of a lumpectomy without approximation of the underlying tissue. While the simple “scoop and run” approach to lumpectomy may work well for smaller tumors, declivity of the skin and/or displacement of the nipple–areolar complex (NAC) can result at final healing if the lesion removed from the breast is sizable.

For breast conservation to be maximally effective, the cancer must be resected with adequate or wide surgical margins while simultaneously maintaining the breast’s shape and appearance, goals that may prove challenging and in some settings seem to be conflicting (3,4). In 1994, Werner P. Audretsch was one of the first to advocate the use of “oncoplastic surgery” for repair of partial mastectomy defects by combining the techniques of volume reduction with immediate flap reconstruction (5). Although initially used to describe the partial mastectomy combined with large myocutaneous flap reconstruction using the latissimus dorsi or the rectus abdominis muscles, oncoplastic surgery now more commonly describes a series of surgical approaches that utilize partial mastectomy and breast-flap advancement to address tissue defects following wide resection. The most

widely utilized techniques include parallelogram mastopexy lumpectomy (including the lateral segmentectomy variant), batwing mastopexy lumpectomy, donut mastopexy lumpectomy, reduction mastopexy lumpectomy, and central lumpectomy (3,6).

widely utilized techniques include parallelogram mastopexy lumpectomy (including the lateral segmentectomy variant), batwing mastopexy lumpectomy, donut mastopexy lumpectomy, reduction mastopexy lumpectomy, and central lumpectomy (3,6).

The use of oncoplastic surgical techniques for breast conservation allows for wider resections without subsequent tissue deformity, and thereby allows surgeons to achieve wide surgical margins while preserving the shape and appearance of the breast (7). While oncoplastic techniques are varied in type and approach, the general principle of fashioning the tissue resection to the anatomic shape of the cancer minimizes the removal of uninvolved breast tissue while ensuring that wide margins, ideally more than 1 cm, are achieved in an optimal number of patients (3,6). The indications, as well as the contraindications, for oncoplastic surgery are the same as those of traditional breast conserving surgery. Such techniques are offered only to those otherwise believed to be breast preservation candidates, including patients with single quadrant disease and individuals who can tolerate and have access to postsurgical radiation therapy.

The techniques described in this chapter are those oncological resections that use breast-flap advancement (so-called tissue displacement techniques). Compared with breast reconstruction using a myocutaneous flap, the breast flap advancement technique is easily learned and implemented by breast surgeons, even those lacking formal plastic surgery training. In a review of 84 women who underwent partial mastectomy and radiation therapy, Kronowitz and colleagues showed that immediate repair of partial mastectomy defects with local tissues results in fewer complications (23% vs. 67%) and better aesthetic outcomes (57% vs. 33%) than that with a latissimus dorsi flap, which some surgeons used for delayed reconstructions (8,9).

General

Patients should undergo standard preoperative history and physical, with the elements of gynecologic, family, and social history including smoking emphasized. Special attention should be given to any prior breast surgical history, including the placement of breast implants. Preoperative laboratory work, such as complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel including liver function tests, and tumor markers are generally obtained as initial staging tests, as is a two-view chest radiograph. Core biopsy should be performed and conclusive proof of malignancy documented, with mandatory internal review of all external pathology slides required at our institution.

Imaging

Patients being considered for oncoplastic lumpectomy should undergo a standard preoperative breast imaging workup, which typically includes some combination of mammography, ultrasound, and in selected circumstances breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Although mammography may underestimate the extent of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) by as much as 1 to 2 cm, especially when the fine, granular microcalcifications generally seen with DCIS are present, it is still warranted and is often the initial diagnostic study (10).

Although controversial, the use of MRI may contribute greatly to the surgeon’s ability to preoperatively determine the extent of disease present, especially for more mammographically subtle or occult cancers. Compared with mammographic and ultrasound images, the extent of disease seen on MRI may correlate best with the extent of tumor found at pathologic evaluation. In addition, MRI has the lowest false-negative rate in detecting invasive lobular carcinoma (11). Although its sensitivity for detection of invasive breast cancer is high, MRI unfortunately has a low specificity of 67.7% in the diagnosis of breast cancer before biopsy (12). Up to one-third of MRI studies will show some area of enhancement that needs further assessment that ultimately proves to be histologically benign breast

tissue (3). A consensus statement from the American Society of Breast Surgeons updated in 2007 supports the use of MRI for determining ipsilateral tumor extent or the presence of contralateral disease, in patients with a proven breast cancer (especially those with invasive lobular carcinoma) when dense breast tissue precludes an accurate mammographic assessment (13). For cancers containing both invasive and noninvasive components, a combination of imaging methods (mammography with magnification views, ultrasonography, and/or MRI) may yield the best estimate of overall tumor size (14).

tissue (3). A consensus statement from the American Society of Breast Surgeons updated in 2007 supports the use of MRI for determining ipsilateral tumor extent or the presence of contralateral disease, in patients with a proven breast cancer (especially those with invasive lobular carcinoma) when dense breast tissue precludes an accurate mammographic assessment (13). For cancers containing both invasive and noninvasive components, a combination of imaging methods (mammography with magnification views, ultrasonography, and/or MRI) may yield the best estimate of overall tumor size (14).

Preoperative Wire Localization

Once a patient commits to breast conservation, decisions regarding the use of preoperative wire localization for nonpalpable malignancies must be made. In planning oncoplastic resections, the surgeon needs to accurately identify the area requiring removal. Silverstein and colleagues (15) previously suggested the preoperative placement of 2 to 4 bracketing wires to delineate the boundaries of a single lesion. In a study by Liberman and colleagues, wire bracketing of 42 lesions allowed for complete removal of suspicious calcifications in 34 (81.0%) (16). It has been suggested that single wire localization of large breast lesions is more likely to result in positive margins, because the surgeon lacks landmarks to determine where the true boundaries of nonpalpable disease are located. For such scenarios, multiple bracketing wires may assist the surgeon in achieving complete excision at the initial intervention.

Relevant Anatomy

A comprehensive understanding of normal ductal anatomy, as well as its influence on the distribution of cancer in the breast, is critical to planning an oncoplastic partial mastectomy (3,6). The modern anatomic analysis of ductal anatomy suggests that the number of major ductal systems is probably fewer than 10 (17). The size of ductal segments is variable and while some ducts pass radially from the nipple to the periphery of the breast, others travel directly back from the nipple toward the chest wall (see Fig. 6.1A and B). In contrast, the well-collateralized breast vasculature allows the surgeon to remodel large amounts of fibroglandular tissue within the skin envelope without a major risk of breast devascularization and/or necrosis. The most common source of arterial blood supply in the human breast arises from the axillary and internal mammary arteries (see Fig. 25.2B). By maintaining communication with one of these two arterial connections and by limiting the degree of dissection between the fibroglandular tissue and skin, an adequate blood supply for the breast parenchyma is maintained during tissue advancement and mastopexy closure.

Preoperative Marking

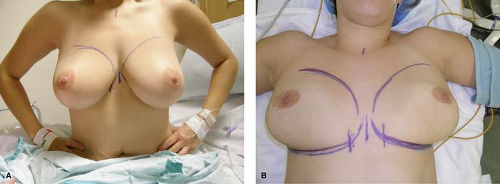

Before the procedure, skin landmarks should be marked with the patient in the upright, sitting position. Relevant landmarks to be identified include the inframammary crease, the anterior axillary fold at the pectoralis major muscle, the posterior axillary fold of the latissimus dorsi muscle, the sternal border of the breast, and the periareolar circle. Identifying these entities with the patient in the upright position is very important to the final cosmetic outcome, because these anatomic sites may prove challenging to accurately locate once the patient is anesthetized and lying supine on the operating room table (Fig. 24.1A and B).

Positioning

For all oncoplastic techniques, the patient should be supine on the operating room table, with the arms abducted and secured. It is preferable to have both breasts prepped

and draped into the field so that visual comparison with the patient in a beach chair position is possible as the wound is closed. Such an approach allows the surgeon to identify any areas of unnecessary tugging or dimpling, which are inadvertently created so that they can be corrected.

and draped into the field so that visual comparison with the patient in a beach chair position is possible as the wound is closed. Such an approach allows the surgeon to identify any areas of unnecessary tugging or dimpling, which are inadvertently created so that they can be corrected.

Description of Individual Oncoplastic Techniques

Parallelogram Mastopexy Lumpectomy (Figs. 24.2 and 24.3)

This technique involves removal of the island of skin that is located directly superficial to the area of known disease. The parallelogram shape, when properly proportioned, guarantees that the two skin edges that are reapproximated at closure will be equidistant. This approach is most commonly used for superior pole or lateral cancers, with the skin incision lines designed to follow Kraissl lines, which follow the natural skin wrinkles and are generally oriented horizontally on the skin (18). The parallelogram incision allows for greater glandular exposure than the typical curvilinear incision of the traditional lumpectomy, while skin island excision avoids excessive, redundant skin from being left behind after excision. For lesions located in the upper inner quadrant, skin island excisions should be small, or the resection should be performed using a simple reapproximation of breast tissue and skin without removal of a skin island (19).

Incision

A rounded parallelogram with two equal length lines is drawn, thus marking the skin island to be excised in conjunction with the underlying target lesion and surrounding tissues (Figs. 24.2A and 24.3A

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree