Occupational Skin Diseases Due to Irritants and Allergens: Introduction

|

Occupational dermatoses are any abnormal conditions of the skin caused or aggravated by substances or processes associated with the work environment. Occupational skin diseases (OSDs) are a major public health problem because they are common, are often chronic, and have significant economic impact on society and on workers.1 A thorough knowledge of potential irritants, allergens, and other causative factors in the workplace, as well as the workers’ compensation system, is essential for the dermatologist dealing with occupational dermatoses.

Historical Aspects and Resources

![]() Paracelsus (1498–1541), in his Morbis Metallicus, was the first to write about OSD, including changes in the skin caused by salt compounds. Agricola described deep skin ulcers in his book about metalworkers at the same time. Ramazzini (1700), the father of modern occupational medicine, made observations about OSD in his classical work De Morbis Artificium Diatriba. Sir Percival Pott (1775) described carcinoma of the scrotum among chimney sweeps; at the same time other authors described and studied OSD and contact dermatitis. Earlier texts include Prosser White’s The Dermatergoses or Occupational Afflictions of the Skin (1915), and Schwartz, Tulipan, and Birmingham’s Occupational Diseases of the Skin (1957). Selected current resources for more in-depth information are listed in eTable 211-0.1.

Paracelsus (1498–1541), in his Morbis Metallicus, was the first to write about OSD, including changes in the skin caused by salt compounds. Agricola described deep skin ulcers in his book about metalworkers at the same time. Ramazzini (1700), the father of modern occupational medicine, made observations about OSD in his classical work De Morbis Artificium Diatriba. Sir Percival Pott (1775) described carcinoma of the scrotum among chimney sweeps; at the same time other authors described and studied OSD and contact dermatitis. Earlier texts include Prosser White’s The Dermatergoses or Occupational Afflictions of the Skin (1915), and Schwartz, Tulipan, and Birmingham’s Occupational Diseases of the Skin (1957). Selected current resources for more in-depth information are listed in eTable 211-0.1.

Select Articles from Special Journal Issues or Books

|

Selected Academic Journals

|

|

Textbooks

|

Handbooks and Manuals and Guides

|

Internet Resources (Current and Active—Use Search Box on each site to retrieve information on specific chemical, occupation, disease, or related questions)

|

Epidemiology

The US Department of Labor publishes annual incidence statistics on the safety and health of employees in private industry (http://www.bls.gov/). In 2008, of the 3.8 million nonfatal job related injuries and illnesses reported among the private industry establishments, 5.1% (193,800 cases) were work-related illnesses, of these, skin disorders were the second most common reported illness, accounting for almost 38,000 cases.2 Occupational contact dermatitis is the most commonly reported OSD, and in most countries, the reported incidence of occupational contact dermatitis varies from 5 to 19 cases per 10,000 full-time workers per year.3 Incidence rates also vary based on the specialty of the reporting physicians; rates are six to eight times higher in some studies when cases are reported by occupational physicians rather than by dermatologists.4

The number of OSD cases has declined,5 especially in the past 8 years, possibly due to better prevention, the ease with which workers’ compensation cases are accepted, and a change in reporting patterns of employees or employers.6 However, a large number of minor or transient cases still go unreported or untreated, so the exact incidence is not known. Occupational skin disease still accounts for a significant percentage of days away from work. In 2008, dermatitis led to 3,170 (8.4%) of the skin disease cases resulting in days away from work and 2,630 (83%) of these cases were caused by contact dermatitis.2

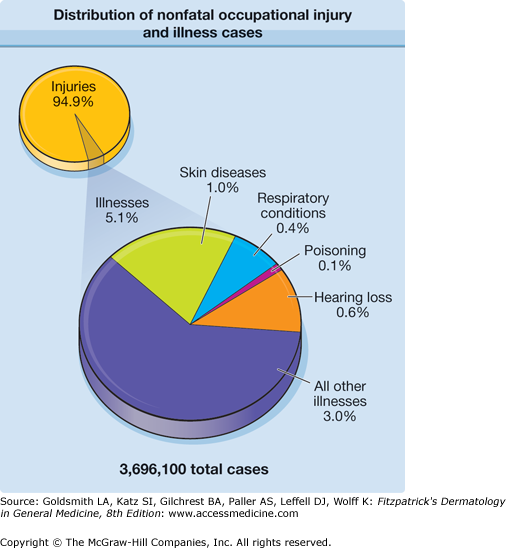

Distribution of nonfatal occupational injury and illness cases by category is demonstrated in Figure 211-1. Surface wounds and bruises and trauma-induced injuries are not considered among the skin disease and illnesses. Surface wounds and bruises accounted for 11,2870 (12.24%) of all traumatic injuries and disorders cases involving days away from work in 2008.7

Figure 211-1

Distribution of nonfatal occupational injury and illness cases by category of illness; private industry; 2008. Only 5% of injury and illness cases reported among private industry establishments in 2008 were illnesses. Nearly 6 in 10 illnesses were categorized as “all other illnesses,” which includes such things as repetitive motion cases and other systemic diseases and disorders. (Adapted from US Bureau of Labor Statistics: 2008 Survey of Occupational Injuries & Illnesses, http://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/os/osch0039.pdf, accessed Feb 7, 2009.)41

Irritant Contact Dermatitis

Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) is a nonimmunologic inflammatory reaction of the skin to contact with a chemical, physical, or biologic agent. ICD is the most common OSD, accounting for up to 80% of cases, although some authors have found a relatively equal distribution of ICD and allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).3Chapter 48 discusses ICD in detail. Exogenous and endogenous factors influencing ICD are listed in Tables 48-1 and 48-2. In addition to the more common acute and chronic eczematous reactions, the clinical spectrum of ICD includes ulceration, folliculitis, acneiform eruptions, miliaria, pigmentary alterations, alopecia, contact urticaria, and granulomatous reactions (Table 211-1).8

|

|

The two major types of occupational ICD are acute ICD and cumulative ICD. These and the many other subtypes are discussed in Table 48-3, which summarizes their time onset and prognosis.

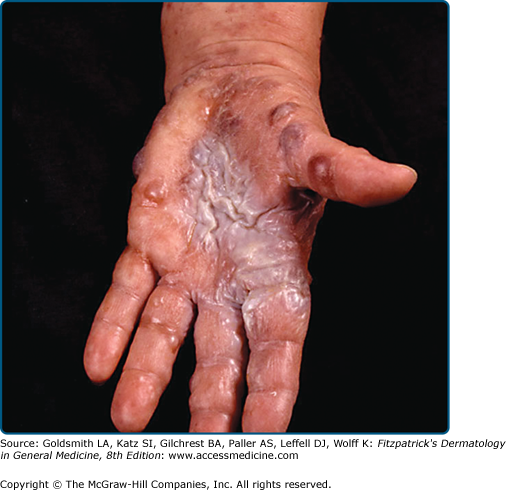

Acute eczematous dermatitis after exposure to a potent irritant, often an acid or alkali, may overlap with chemical burns. Highly irritating chemicals may induce a reaction in anyone if the concentration and duration of action are sufficient. The intrinsic nature of the chemical is also important. Common irritants in the workplace are discussed in Common Occupational Irritants later in the chapter. In national statistics for work-related injuries, acute ICD reactions are often classified as chemical burns (Fig. 211-2).

Cumulative ICD, the most common type of ICD, develops slowly after multiple subthreshold exposures to mild irritants (soap, water, detergents, industrial cleansers, solvents, etc.) under a variety of conditions.9 Some of the high-risk occupations for ICD are listed in Table 211-2. For a comprehensive list, see the sources presented in eTable 211-0.1. The other categories of ICD, as well as predisposing factors, including exogenous as well as endogenous factors, are discussed in Chapter 48. Atopic individuals have an increased susceptibility to skin irritation and account for a large percentage of workers’ compensation dermatitis claims.

Occupation | Irritants | Allergens |

|---|---|---|

Agricultural workers | Fertilizers, germicides, dust, diesel, gasoline, oils, pesticides, plants, solvents, wet-work | Pesticides, animal feeds, barley and oats, fungicides, germicidal products, cement, plants, veterinary medications, wood dust, preservatives, wool |

Bakers | Acids, flour, spices, soaps and detergents, oven cleaners, essential oils, yeast, enzymes | Ammonium persulfate; benzoyl peroxide; dyes; essential oils; enzymes; flavors; flour; some fruits |

Construction workers | Acids, fibrous glass, concrete, solvents, hand cleaners | Cement, chromium, chromium compounds, cobalt, epoxy resins, nickel, resins, rubber allergens, wood dust |

Cooks | Wet work, soaps and detergents, vegetable and fruit juices, raw meat and fish, spices, sugar and flour, heat | Flavors and spices, formaldehyde, garlic, sodium metabisulfite (antioxidant for vegetables) |

Cosmetologists | Soaps and detergents, bleaches, solvents, permanent wave solutions, shampoos, wet-work | Dyes, amine-based products including parphenylene diamine, glyceryl monothioglycolate (perming solution), rosin, preservatives, rubber allergens, ethylmethacrylate, methylmethacrylate |

Dentists and Dental technicians | Wet work, adhesives (epoxy and cyanoacrylates), essential oils, orthodontic plasters, amalgam mixtures, solvents | Dental impression material, eugenol, anesthetics, mercury, disinfectants, methacrylates, latex, rubber accelerators |

Florists | Wet work, soaps and detergents, fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, mechanical and chemical plant irritants | Plants, pesticides, insecticides |

Health care workers | Wet work, soaps and detergents, alcohol, ethylene oxide, medications | Latex gloves, anaesthetics, antibiotics and antiseptics, phenothiazines, formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde, chloroxylenol |

Housekeepers | Wet work, soaps and detergents, cleaners, polishes, oven cleaners, disinfectants | Potassium dichromate, preservatives, rubber accelerators, latex |

Machinists | Solvents, coolants, cutting oils, degreasers, acids, corrosion inhibitors, heat, soaps and detergents, metal filings and swarf | Additives/preservatives in cutting fluids, chromium, nickel |

Automobile Mechanics | Abrasive skin cleaners, diesel, gasoline, greases, oils, solvent, transmission fluid, motor oils | Chromium, cobalt, epoxy resin; nickel |

Painters | Paints, solvents, adhesives, paint removers, paintbrush cleaners, soaps and detergents | Turpentine, thinners, chromium, formaldehyde, epoxy products, polyester resins |

Workers, especially atopic individuals who are subjected to low relative humidity at work (Table 211-3),10 are also at risk for developing dermatitis, especially with the presence of other irritants. When relative humidity is below 35%–40%, the stratum corneum becomes drier and more brittle, and shows increasing permeability to marginal irritants. Symptoms such as pruritus and burning may be the only complaints and are more distressing than physical signs, which may involve exposed or covered areas. Differential diagnosis includes irritation from airborne substances, other dermatoses, and psychogenic causes.

|

Airborne irritants are an important cause of contact dermatitis. The pattern is fairly characteristic, with subjective symptoms of stinging, burning, or smarting sensations. Objective findings range from barely visible diffuse lesions to more severe dermatitis of the eyelids, cheeks, nasal folds, and neck. Some airborne irritant particles cause symptoms only if occluded under clothing in the flexures and other intertriginous body areas.

The most frequent causes are irritating dusts and volatile chemicals, such as solvents, ammonia, formaldehyde, epoxy resins and their hardeners, cement dust, fibrous glass, and sawdust, especially from irritating woods.11 See Table 48-4 for a list of other airborne irritants.

The diagnosis of ICD is based on a history of exposure to a known potential irritant, the clinical appearance, and the distribution of lesions.12 Subacute and chronic irritant dermatitis are almost always diagnoses of exclusion. Patch testing (see Chapter 13) helps to distinguish ACD from ICD or to diagnose a superimposed ACD or ICD. More detailed criteria for the clinical diagnosis of ICD are discussed in Chapter 48 and especially Box 48-1 and Table 48-7.

Soaps and detergents are weak skin irritants; however, excessive use can cause cumulative insult dermatitis in susceptible individuals. The choice of cleanser varies with the job for which it is intended; for example, machinists and auto mechanics need a cleanser with a high detergent and abrasive action. The inappropriate use of products intended as industrial cleansers can also result in dermatitis.

Waterless hand cleaners are formulated to remove tough oil and grease stains and are widely used at work sites where there is no convenient source of water. They should be applied sparingly because they may contain petroleum-derived solvents and may result in dermatitis if overused. Instant hand sanitizers, which often contain high concentrations of alcohol, can be drying to the skin.

Chemical burns are an important cause of occupational injury.13 Copious irrigation is the primary method of treating all chemical burns; however, certain types of burns require specific antidotes and therapies (Table 211-4).14

Chemical | Treatment Basics (Then Transport to Hospital Emergency Department for Further Evaluation and Treatment) |

|---|---|

Burning metal fragments of sodium, potassium, and lithium | Extinguish with Class D fire extinguisher (containing sodium chloride, sodium carbonate or graphite base) or with sand; cover with mineral oil; extract metal particles mechanically.a |

Hydrofluoric acid | Flush with running water; then administer calcium gluconate gel (2.5%) followed by intralesional injection, if needed. |

White Phosphorus | Remove particles mechanically; wash with soap and water; then apply copper (CuSO4) sulfate in water for several minutes, remove black copper phosphide, and wash with water. Vigorous water irrigation and removal of phosphorus particles mechanically; The use of a Wood lamp (ultraviolet light) results in the fluorescing of the white phosphorus and may facilitate its removal. A brief rinse with 1% copper sulfate solution may be helpful. Copper sulfate combines with phosphorus to form a dark-copper phosphide coating on the particles that makes them easier to see and debride, and also impedes further oxidation. However, copper sulfate can cause hemolysis and hemoglobinuria, and should be used with caution.74 More recently Kaushik and Bird recommend vigorous water washing rather than using copper sulfate.75 |

Phenolic compounds | Decontaminate with undiluted 200–400 molecular weight polyethylene glycol (PEG), which can be located in the chemical section of hospital pharmacies, followed by copious water irrigation. Isopropanol or glycerol may be substituted if PEG is not available.76 Initial soap and water washing followed by treatment with polyethylene glycol 300 or 400 or ethanol (10%) in water. |

Bromine or iodine | Wash frequently with soap and water followed by treatment with 5% sodium thiosulfate. |

Inorganic acids are used in large quantities in industry; some of the occupations at risk for exposure are listed in Table 211-5. Acids are common causes of chemical burns and can cause erythema, blistering and necrosis, and discoloration of the skin. Mechanisms of action of common industrial irritants, including acids, are listed in Table 211-6.

Chemical | Industries Presenting Risk |

|---|---|

Acids | |

Sulfuric | Manufacture of fertilizers, inorganic pigments, textile fibers, explosives, pulp and paper |

Hydrochloric | Production of fertilizers, dyes, paints, and soaps |

Formic | Textile industry (dyeing and finishing), leather manufacture (delimer and neutralizer), production of natural latex (coagulant) |

Acrylic | Manufacture of acrylic plastics (monomer) |

Chromic | Chrome plating, copper stripping, and aluminum anodizing operations |

Hydrofluoric | Etching and frosting of glass, rust removal, dry cleaning (spot cleaning) |

| Alkalis | |

Calcium, sodium, and potassium hydroxides | Manufacture of bleaches, dyes, vitamins, plastics, pulp and paper, and soaps and detergents |

Others | |

Arsenic | Smelting of copper, gold, lead, and other metals; semiconductor industry |

Beryllium | Aerospace and other industries involved in the production of hard, corrosion-resistant alloys |

Cobalt | Manufacture of alloys, ceramics, electronics, magnets, paints and varnishes, or cosmetics; electroplating |

Mercury | Industries involved in the manufacture or use of bactericides, dental amalgams, and catalysts |

Phosphorus | Manufacture of insecticides and fertilizers |

Action | Irritant |

|---|---|

Keratin and protein dissolution | Alkalis, soaps |

Lipid dissolution | Organic solvents |

Dehydration | Inorganic acids Anhydrides Alkalis (calcium oxide) |

Oxidation | Bleaches |

Reduction | Salicylic acid Formic acid Oxalic acid |

Keratogenesis | Arsenic Tars Petroleum |

Organic acids, such as acetic, acrylic, formic, glycolic, benzoic, and salicylic acids, are less irritating than some other acids but can cause chronic irritant dermatitis after prolonged exposure. Formic acid has greater corrosive potential than other organic acids. Fatty acids, such as palmitic, oleic, and stearic acids tend to have low irritant potential.

Hydrofluoric acid (HF) is extremely irritating, even in low concentrations (15%–20%). Fluoride ions penetrate deep into the tissues and bind to calcium and magnesium ions, causing severe tissue damage including bone destruction, especially of the terminal digits of the hand.14 After exposure to lower concentrations of HF, the onset of symptoms may be delayed until release of fluoride ions occurs in deep tissues. Exposure to HF is a medical emergency requiring topical or subcutaneous administration of calcium gluconate after lavage to bind the fluoride ions (see Table 211-4).

Chromic acid is highly irritating, causing ulcerations of the skin (“chrome holes”) and perforation of the nasal septum. It can be absorbed and lead to renal failure.15

Alkalis saponify surface lipids and penetrate easily, leading to severe and extensive tissue destruction, including deep ulcerations that heal very slowly (see Table 211-5).

Exposure to wet cement may cause severe alkaline and thermal burns due to the exothermic reaction of calcium oxide with water to form calcium hydroxide.16 Kneeling in wet cement for prolonged periods leads to deep burns of the knees (“cement knees”) and shins.17 Burns may also result from the trapping of wet cement in gloves and boots.

Phosphorus can cause deep, destructive burns. It ignites spontaneously on exposure to air. The affected area should be kept moist until the chemical is completely removed. Severe metabolic derangements have been reported after phosphorus burns, and patients should be closely monitored for multiorgan failure.18

Ethylene oxide burns may result from contact with porous materials and devices that have been sterilized with ethylene oxide but not properly aerated.19 Ethylene oxide may cause delayed irritant reactions (see Table 48-5). Rarely, allergic contact dermatitis is reported to ethylene oxide.66

Phenol is rapidly absorbed through intact skin and can cause local necrosis and nerve damage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree