Chapter 26 Notchplasty

Anatomy

The subtle anatomy of the intercondylar notch in three dimensions plays an important role in the incidence of ACL injuries as well as in optimizing surgical techniques of notchplasty and the ultimate outcome of reconstructions. Several investigators1–5 have shown that a small notch width or a small notch width index (notch width divided by condylar width) is directly correlated to increased risk of ACL injuries, especially in women (Fig. 26-1). A debate has surfaced that it is not a small notch width alone that leads to an increased risk of injury but rather a smaller ligament within the notch that may play a role. Shelbourne et al6 showed when reconstruction is performed with the same size of graft, regardless of notch width or gender, the success rates were similar. Anderson et al7 compared magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of groups of male and female basketball players and found smaller ligaments in the female athletes as well as differences in notch width. Charlton et al8 found gender variations in both notch width and ACL volume in the groups they compared. Regardless of the debate, it is clear that radiographic findings of a small notch is predictive of ACL injury. In addition, the shape of the notch on an anteroposterior (AP) notch view may also play a role regarding ACL injury risk, with an A-framed notch being relatively more stenotic and leading to increased risk of injury compared with a wider and forgiving inverted U-shaped notch. It should be emphasized that no one is currently promoting prophylactic notchplasty in athletes with an intact ACL who incidentally have been found to have a small notch.

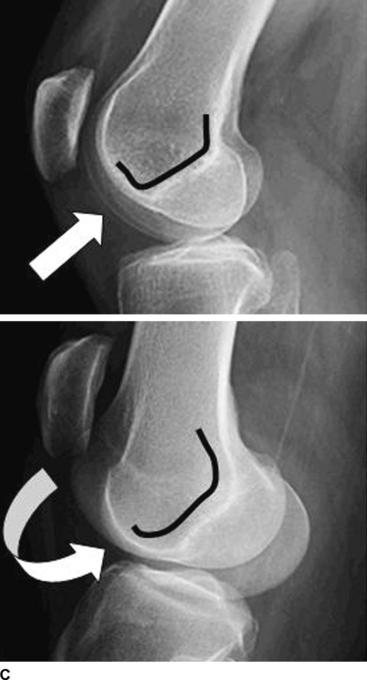

While the AP perspective is clearly important when evaluating the intercondylar notch, the lateral perspective may be as or more important for preoperative planning. On a lateral radiograph, Blumensaat’s line represents the roof of the intercondylar notch. The slope (angular orientation relative to the femur), position (anterior/posterior translational position relative to the central axis of the femur), and trueness (absolutely straight or curved at the ends) are highly variable among patients (Fig. 26-2). Numerous authors have demonstrated an increased risk of ACL reconstruction failure or postoperative extension loss if graft roof impingement is apparent on the lateral perspective.9,10 Howell et al10–13 have been instrumental in increasing the surgical community’s awareness of the importance of identifying potential graft roof impingement preoperatively to guide either tunnel placement or the extent of notchplasty intraoperatively. A preoperative lateral radiograph should be routinely obtained in full extension. If the slope of the roof of the notch is acute or its relative position is too posterior, either the tibial tunnel should be placed more posteriorly to avoid impingement14–16 or an aggressive roofplasty needs to be performed.16,17 Failure to recognize this impingement will lead to an increased risk of graft failure.

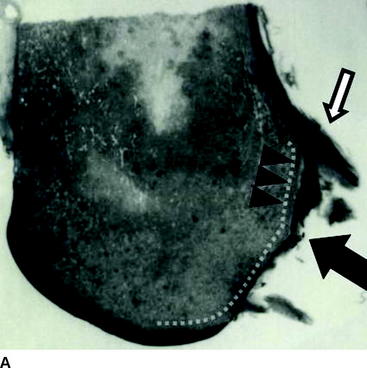

Review of the preoperative lateral radiograph should also assess the trueness of Blumensaat’s line. Is it a straight line from front to back with sharp corners or edges at the inlet and outlet of the notch, or is it rounded at the ends with bumps or curves in the middle that may affect femoral tunnel selection? The roof of the notch is rarely perfectly flat; it usually has a slight curve at the inlet (anterior aspect of the notch) and the outlet (the over-the-back) position. Anteriorly, the gentle transitioning curve or blending of the femoral groove and femoral condyles into the articular surface prevents a sharp edge or corner cutting into the anterior aspect of the ACL in full extension. Posteriorly within the notch, a change in slope occurs approximately 1 cm anterior to the true over-the-back position. This change of slope is usually located at the anterior edge of the leading aspect of the ACL insertion onto the lateral femoral condyle and has been termed the “resident’s ridge” by Clancy18 (Fig. 26-3). Preoperative or intraoperative awareness of the resident’s ridge is essential for optimal placement of the femoral tunnel and successful outcome of the reconstruction. If the change of slope is acute and mistaken for the true over-the-back position, the femoral tunnel will be placed too far anteriorly and lead to one of the most common causes of failure for ACL reconstructions. At the time of notchplasty, a prominent resident’s ridge should be taken down with a bur or osteotome to confirm optimal placement of the femoral tunnel guide and ensure proper positioning of the femoral tunnel. Finally, the true outlet of the notch or over-the-back position on the femur is frequently gently curved, making it difficult to lock in the extended tongues of the femoral guides designed to offset the tunnel position relative to the posterior cortex. This edge may need to be flattened or a preliminary concavity created at the site of the femoral tunnel to allow the guide to be properly seated.