Non-Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis: Introduction

|

Non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis (NLCH), or class II histiocytosis, represents a broad group of different disorders characterized by the proliferation of histiocytes other than Langerhans cell (LC) (Table 148-1).

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG)

Generalized eruptive histiocytosis (GEH)

Xanthoma disseminatum (XD)

Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH)

Progressive nodular histiocytosis (PNH) Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (SHML) |

In some textbooks, these diseases are gathered under the term: macrophage/dermal dendritic cell disorders. In 2001, Zelger et al suggested a unifying approach to understand this disease group. They identified different types of macrophages in the prototype lesion, juvenile xanthogranuloma, and then used this morphology to subcategorize the diseases.

Clinicopathologic overlap makes it difficult to place some patients exactly into one defined entity, indicating a close relationship between these disorders. While many of these disorders may feature foamy cells, affected patients are normolipemic. In all instances, the etiology and pathogenesis are unknown.1

Most of these cells share the same immunophenotypes, but the resulting disorders differ in clinical presentation and course. Although all NLCH disorders are considered reactive with no clinical evidence of malignancy, some forms, as with class I histiocytosis (Langerhans cell histiocytosis or LCH), can be invasive and therefore they are not necessarily biologically benign. Patients have been described who have developed both LCH and an NLCH, particularly, juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG).

These cases seem to demonstrate a relationship between LCH and NLCH.2 According to some authors the dendritic cell is the presumed cell of origin of both LCH and NLCH, leading to the shared categorization of these diseases as dendritic cell-related disorders and separated from macrophage-related proliferations such as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (SHML), also known as Rosai–Dorfman disease. However, the coexistence of LCH and cutaneous SHML has also been reported, further complicating the complex relationships among histiocytic disorders. See Table 147-2 for a list of the recommended laboratory evaluations for a patient with LCH and Table 147-3 for a list of other investigations that should be carried out in LCH.

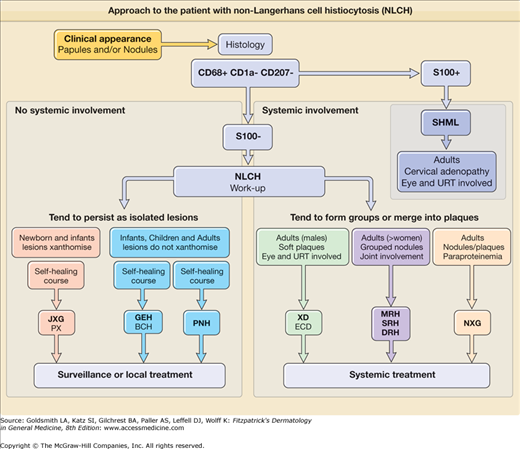

Although impossible to perfectly correlate histologic features and immunophenotype with either clinical presentation or course of a single disease, one practical classification is infantile versus adult disease. Infantile forms with individual papulonodular lesions tend to be almost all cutaneous and self-healing [e.g., JXG, generalized eruptive histiocytosis (GEH), benign cephalic histiocytosis (BCH)], whereas the adult forms with coalescing plaque-like lesions tend often to be systemic and progressive/aggressive [e.g., Erdheim–Chester disease (ECD); necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG); SHML]. Other rare forms including hereditary progressive mucinous histiocytosis are not discussed. An approach to the patient with NLCH is outlined in Fig. 148-1.

Figure 148-1

Approach to the patient with non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis (NLCH). BCH = benign cephalic histiocytosis; DRH = diffuse cutaneous reticulohistiocytosis; ECD = Erdheim–Chester disease; GEH = generalized eruptive histiocytosis; JXG = juvenile xanthogranuloma; MRH = multicentric reticulohistiocytosis; NXG = necrobiotic xanthogranuloma; PNH = progressive nodular histiocytosis; PX = papular xanthoma; SRH = solitary cutaneous reticulohistiocytosis; SHML = sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy; URT = upper respiratory tract; XD = xanthoma disseminatum.

Epidemiology

JXG accounts for 80%–90% of cases of NLCH. All of the other NLCHs are rare. The author has encountered almost 300 cases in the past 35 years. There is no sexual or racial predilection. JXG appears within the first year of life in approximately 80% of cases; in 20%–35% of cases, it is congenital. Approximately, 30 adult cases are reported in the literature. There is a slight male predominance among individuals with solitary JXG lesions and a strong male predominance among those with multiple cutaneous lesions. Papular xanthoma (PX), considered a variant of JXG, is a rare disorder; fewer than 20 cases have been described. The onset of PX in children is usually during the first year of life. The disease seems to be more frequent in males. GEH is rare, with approximately 40 cases described, of which 10 were in children. It may start at any age, with reports of onset ranging from 3 months to 58 years. BCH is also rare. Over the past 3 decades, approximately 30 cases have been described, with the same incidence in boys and girls. The age of onset is 5–34 months (mean, 13.5 months). Progressive nodular histiocytosis (PNH) is an exceptional form described in a few children and adults. Xanthoma disseminatum (XD) is rare (approximately 100 published cases) and affects males more frequently than females. The random nature of the disorder does not permit an exact evaluation of either familial involvement or morbidity. In approximately 60% of patients, onset is before age 25 years. ECD is also rare, and only about 60 cases have been described in 70 years. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH) is an uncommon disorder but has been observed in more than 100 individuals reported up to 1990, with the purely cutaneous forms seen in more than 50 patients. Caucasians are affected in more than 85% of cases, and women are more frequently affected than men (female–male ratio of 3:1). In general, MRH affects adults 40 years of age, but the disease may appear during adolescence and rarely in childhood (pure cutaneous forms). NXG has been described in approximately 60 cases. The age of onset of NXG ranges from 17 to 85 years, and the disease shows no gender predilection. SHML is also a relatively rare disease; approximately 365 cases have been studied. The disease has a worldwide distribution with increased incidence in blacks from Africa and the West Indies. There is no gender predilection. Any age group may be affected, but 80% of cases occur in the first or second decade of life.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of NLCH is unknown. Virus-induced local immune alternation in the transformation of the NLCH has been postulated since previous studies have suggested that the proliferation of histiocytes is a physiologically appropriate response to viral infection.3

MRH may represent an abnormal histiocytic reaction to different stimuli. In forms with solitary lesions, local trauma may play a role, whereas in diffuse forms, the association with internal malignancies and autoimmune diseases suggests an immunologic basis for the initiation of the reaction.

PNH is a progressive disease with no tendency to involute spontaneously. It is thought to entail proliferation of mature spindle-shaped cells and may represent an evolution of another form of NLCH. MRH may evolve from a less developed form of NLCH, such as GEH or adult JXG. It has also been suggested that urokinase released by the activated histiocytes may play a role in the extracellular matrix degradation leading to erosion of cartilage and adjacent bone. The origin and function of the pleomorphic cytoplasmic inclusions that are frequently present in the histiocytes forming the infiltrate in this disease are still debated. They may result from a peculiar kind of endocytosis or from the expression of an exocytosis phenomenon. These unique granules have already been described in several cases of reticulohistiocytosis, and if their presence is confirmed by subsequent observations, they could represent the ultrastructural marker.

The cause of NXG and its link to paraproteinemia are uncertain. It has been suggested that serum immunoglobulins complexed with lipid become deposited in the skin, eliciting a giant cell foreign-body reaction. Another hypothesis is that the paraproteinemia is the primary phenomenon, and a secondary proliferation of macrophages with receptors for the Fc portion of immunoglobulin G occurs. It has also been proposed that the paraprotein in NXG has functional features of a lipoprotein that may bind to lipoprotein receptors of histiocytes and induce granuloma formation. Mutations in SLC29A3, encoding an equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT3), have recently been shown to cause both familial histiocytosis syndrome (Faisalabad histiocytosis) and familial SHML.4

Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

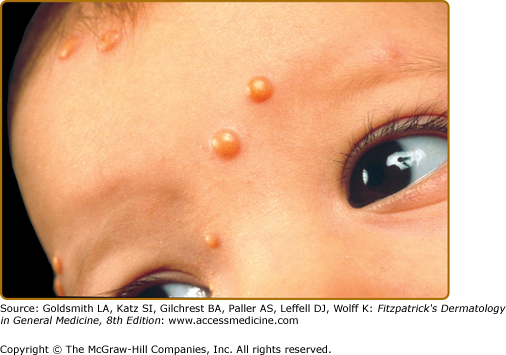

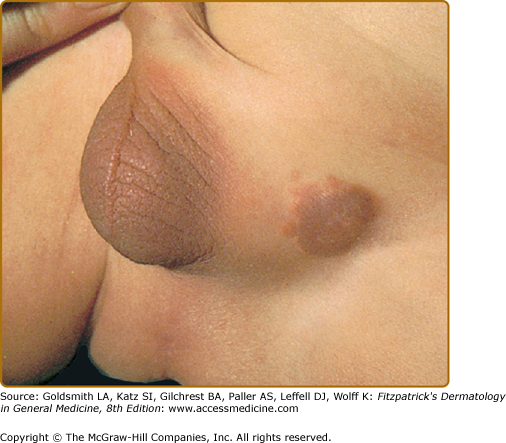

JXG is a benign, self-healing disorder that is characterized by asymptomatic yellowish papulonodular lesions of the skin and other organs in the absence of a metabolic disorder. Lesions consist of an infiltrate of histiocytes with a progressively greater degree of lipidation. Two main clinical forms can be distinguished, a papular and a nodular form. In both the lesions are initially orange–red or red–brown but quickly turn yellowish. The papular form (Fig. 148-2) is characterized by numerous (up to 100) firm hemispheric lesions 2–5 mm in diameter. These lesions are irregularly scattered throughout the skin but are located mainly on the upper part of the body. PX is considered to be a form of JXG in which the lesions rapidly become xanthomatous. PX lesions range from 2 to 12 mm and show a generalized distribution with no tendency to merge into plaques. The nodular form (Fig. 148-3) is less frequent and occurs as one or a few lesions. Such nodules are generally round, 10–20 mm in diameter, and translucent, and might show telangiectases on their surface. The term giant juvenile xanthogranuloma is applied to lesions larger than 2 cm. Unusual clinical variants have been also reported. The mixed form is characterized by the simultaneous presence of both small and large nodules. The term juvenile xanthogranuloma en plaque defines a group of JXG lesions with a tendency to coalesce into a plaque as the only expression of the disease. In one study, 67% of 174 cases involved solitary papular lesions, and an additional 16% showed solitary nodular lesions. Multiple cutaneous lesions were noted in 7% of affected individuals, a solitary extracutaneous lesion in 5%, and multiple cutaneous and visceral-systemic lesions in an additional 5%.

Recently, two new variants have been described. The first was a case with skin lesions consisting of bluish papules and nodules (mimicking a “blueberry muffin baby”) located on the head, trunk, and proximal extremities. The second, “multiple lichenoid JXG,” was characterized by hundreds of discrete papules.5

Ocular involvement is the most typical extracutaneous manifestation. It may precede or follow the cutaneous lesions. Approximately 0.4% of cases exhibit ocular manifestations, usually unilateral.6 Lesions may affect the orbit, iris, ciliary body, cornea, and episclera, and can result in spontaneous hyphema, glaucoma, and blindness. JXG of the uvea is a rare disease that usually responds to systemic steroids or low-dose radiotherapy; aggressive cases can be treated with chlorambucil.7 Therefore, the importance of ocular screening in patients with JXG, especially those with periocular lesions, should be emphasized. However, it is important to realize that the absence of skin lesions should not rule out JXG because skin lesions can often regress spontaneously.

An extremely rare extracutaneous manifestation of the papular variant is central nervous system (CNS) involvement. The nodular form of JXG may occasionally be related to systemic lesions of the lungs, bones, kidneys,8 pericardium, colon, ovaries, and testes. Juvenile chronic myelogenous leukemia (JMML) has been observed in association with this variant of JXG. Café-au-lait macules and JXGs occur together in 20% of individuals with papular JXGs and can be considered an excellent marker of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) (see Chapter 141) during the first years of life, even in the absence at that age of other reliable markers of NF-1. The occurrence of the triad of NF1, JXG, and JMML was first reported case in 1958, but is rare (approximately 20 cases in the literature). However, children with NF1 and JXG have a 20–30-fold higher risk for JMML than patients with NF1 without JXG.9

No abnormalities in laboratory test results are usually found in JXG except in the very rare cases in which juvenile chronic myeloid leukemia is associated with JXG.

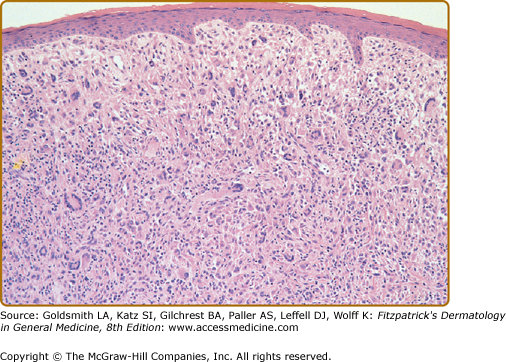

Biopsy sections of JXG lesions show a feature that is common to many NLCHs, i.e., a nonepidermotropic histiocytic infiltrate lacking Langerhans granules. Early lesions of JXG are characterized by a monomorphous, nonlipid-containing histiocytic infiltrate that occupies at least the upper half, and sometimes the entire thickness, of the dermis. Mature lesions (Fig. 148-4) contain foam cells, foreign-body giant cells, and Touton giant cells, mainly distributed in the superficial dermis and on the border of the infiltrate. Lymphocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils are variably associated. Older lesions may show fibrosis. In mature lesions, fat stains yield positive results. The majority of JXG lesional biopsy sections stain positive for CD68/Ki-M1P and factor XIIIa but negative for CD1a and S100 protein. Recently, a 9-month-old boy was clinicopathologically diagnosed as S100-positive JXG. Longitudinal observation revealed that strong S100 reactivity disappeared in parallel with maturation of the lesions within 2 years after the initial diagnosis.10

Under the electron microscope, the histiocytes that characterize the early stage of the disease exhibit pleomorphic nuclei, are rich in pseudopods, and contain many elongated and irregular dense bodies. Clusters of comma-shaped bodies can occasionally be observed. In older lesions, there is a predominance of foam cells, the cytoplasm of which is completely filled with lipid vacuoles, cholesterol clefts, and myeloid bodies. Touton giant cells are extremely large and sometimes contain more than ten nuclei. Lipid material fills the periphery, whereas mitochondria and lysosomes predominate at the center.

The lesions of PX are composed almost entirely of foam cells and Touton giant cells. There is no evidence of a primitive histiocytic phase, and inflammatory cells are scarce or absent. Ultrastructurally, the cytoplasm is completely filled with lipid vacuoles without a limiting membrane, myeloid bodies, and lysosomal inclusions. Comma-shaped bodies are not found in these histiocytes.

The differential diagnosis of JXG is summarized in Box 148-1.

PAPULAR Most Likely | NODULAR Most Likely |

Consider

|

Consider

|

Eye involvement of a JXG lesion can cause severe secondary glaucoma. Lesions compatible with JXG have been described in many other organs as well, including oropharynx, lungs, spleen, liver, testes, heart, pericardium, gut, kidney, pancreas, lymph nodes, bone marrow, and even the CNS, and in rare cases can lead to death.11 Severe multisystemic JXG in infants is a life-threatening disorder, and thus treatment is often required.12 Patients may respond to multiagent chemotherapeutic regimens used to treat LCH.

The cutaneous lesions of JXG tend to flatten with time. Each lesion evolves separately; thus, lesions at different stages of development may be seen in the same patient. Both cutaneous and visceral lesions disappear spontaneously, usually within 3–6 years. The patient’s general health is not impaired, and physical and mental development is normal. Metabolic disturbances have not been identified. In the absence of associated conditions, prognosis is good. However, it is important to recognize that JXG may herald hematopoietic disorders in children and adults.13

Generalized Eruptive Histiocytosis

The skin lesions of GEH consist of an asymptomatic eruption of round or oval papules that are firm, pink or dark red, and range in size from 3 to 10 mm (Fig. 148-5). These lesions appear in successive crops and are usually numerous (in the hundreds). In adults, the lesions are symmetrically distributed and may involve the mucous membranes, whereas in children the lesions are irregularly scattered over the entire body and the mucous membranes are spared.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree