Tumors of Smooth Muscle

The dermis contains smooth muscle fibers in the arrector pili muscles, in the walls of dermal blood vessels, and in the dartos muscle of the scrotum, vulva, nipple, and areola. There are three types of cutaneous smooth muscle lesions: (1) leiomyomas, (2) leiomyosarcomas, and (3) hamartomas. Smooth muscle is recognized histologically by spindle cell shape, eosinophilic, fibrillary cytoplasm, and blunt-ended, oval, “cigar-shaped” nuclei. On immunohistochemical staining, cells express smooth muscle actin and the muscle-specific intermediate filament desmin, but are negative for S100 protein and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA).

|

The exact incidence of leiomyomas is unknown. In one study, the 10-year incidence was 0.04% with the majority of lesions occurring in women.1 Although leiomyomas are thought to be relatively uncommon neoplasms, the actual incidence may be higher than previously believed due to failure to recognize and biopsy the lesion.

Cutaneous leiomyomas are divided into three subsets: (1) solitary or multiple piloleiomyomas originating from the arrector pili muscles; (2) genital leiomyomas originating from the mammillary, dartoic, or labial/vulvar muscles; and (3) angioleiomyomas, originating from vascular smooth muscle. Most leiomyomas are acquired; however, familial inheritance patterns have been described. Especially noteworthy are patients with multiple piloleiomyomas. Starting in early adulthood, these patients present with increasing numbers of tumors, developing as many as 100–1,000 lesions. Transmission appears to be autosomal dominant with variable penetrance.2 Women with multiple piloleiomyomas may also develop uterine leiomyomas, an entity termed multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis (also known as familial leiomyomatosis cutis et uteri or Reed syndrome).2 In addition, some families with multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis have been shown to cluster renal cell cancer, and this has been termed hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. Recently, a loss of function mutation in the gene encoding fumarate hydratase on chromosome 1q42.3–43 has been shown to predispose individuals to these conditions. Fumarate hydratase catalyses the conversion of fumarate to malate in the Krebs cycle but is also considered to be a tumor-suppressor gene.3,4

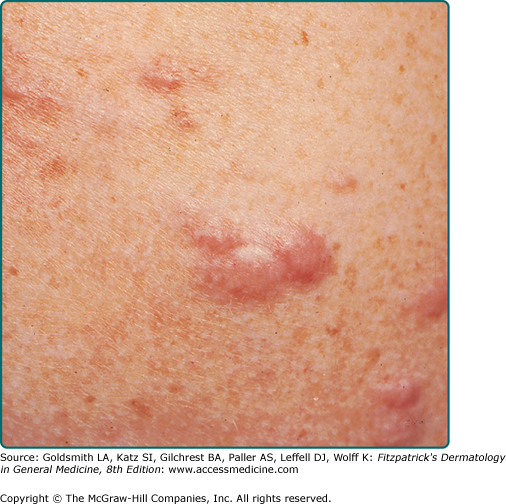

The most common presentation is that of multiple piloleiomyomas.5 Individual lesions range in size from several millimeters to 1 cm and are usually reddish-brown firm papulonodules that are fixed to the skin but freely moveable over underling deeper structures (Fig. 127-1). They can coalesce to form plaques or linear, grouped, or dermatomal patterns.5 The extensor extremities, trunk, and sides of the face and neck are the most common locations. Patients with piloleiomyomas often have pain that may be spontaneous or secondary to cold, pressure, or emotion.2,5–7 Possible explanations for this phenomenon include pressure of the tumor on local nerve fibers and contraction of the smooth muscle fibers.5 Genital leiomyomas are clinically similar to piloleiomyomas except that they are usually asymptomatic.5 They commonly present as solitary, deep papulonodules or occasionally, pedunculated papules on the scrotum, vulva, penis, or areolar region. Angioleiomyomas present most commonly as solitary, painful subcutaneous nodules on the legs in women that can grow to several centimeters in diameter.8

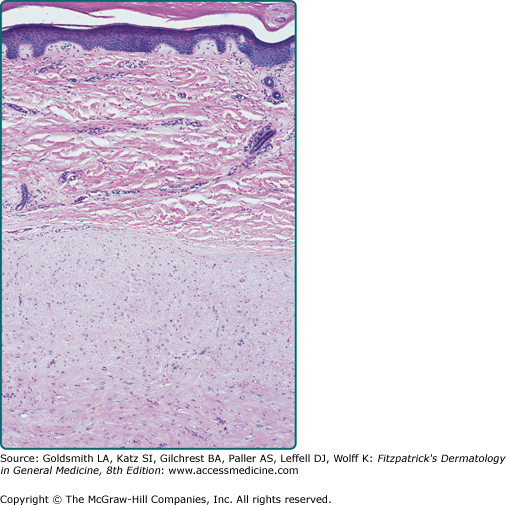

Pilar leiomyomas are composed of a poorly circumscribed proliferation of haphazardly arranged, bland-appearing smooth muscle cells with characteristic eosinophilic cytoplasm, blunt-ended nuclei, and perinuclear halos in cross section. They are located in the dermis and can infiltrate the surrounding tissue with extension into the subcutis. Genital leiomyomas usually resemble pilar leiomyomas. Angioleiomyomas are well-circumscribed, richly vascularized dermal or subcutaneous nodules composed of well-differentiated smooth muscle fibers (Fig. 127-2). Occasionally, the vessel of origin can be identified. Leiomyomas stain positive with smooth-muscle actin and desmin.

Differential diagnosis of leiomyoma includes any flesh-colored or reddish-brown superficial or deep-seated papule or nodule: angiolipoma, glomus tumor, eccrine spiradenoma, neurofibroma, nevus, or lipoma.

Cutaneous leiomyomas do not regress spontaneously, and there does not appear to be risk of malignant degeneration into leiomyosarcoma. A minority of patients may also develop uterine leiomyomas and, in some families, association with renal cell carcinoma has been described. Occasionally, leiomyomas are associated with polycythemia. This may be due to erythropoietin-like activity of leiomyomas, which has been demonstrated in tumor extracts.9

Excision is the treatment of choice for leiomyomas that cause pain or cosmetic concern; however, recurrence is common. In patients with numerous lesions, this method is impractical. Carbon dioxide laser ablation was reported as an effective modality10 whereas cryotherapy and electrosurgery have been used with disappointing results.11 Pain may be a significant source of morbidity and, when surgical intervention is not possible, potential treatment options include nitroglycerin, phenoxybenzamine, nifedipine, gabapentin, intralesional botulinum toxin, or topical analgesics.2,12–15

|

Exact incidence is unknown, but older studies suggest that leiomyosarcomas comprise approximately 3% of soft-tissue sarcomas.16 Superficial leiomyosarcoma occurs in all age groups, and there appears to be no gender predilection.

Leiomyosarcoma is a rare, malignant mesenchymal tumor of smooth muscle origin usually found in the uterus, the retroperitoneum, gastrointestinal tract, or deep soft tissue. The term superficial leiomyosarcomas refers to those tumors whose primary site of origin is the skin. Those derived from arrector pili or genital smooth muscles are termed cutaneous leiomyosarcomas, and those derived from blood vessel smooth muscle are termed subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas. In some cases, tumors have arisen in sites of earlier radiotherapy or trauma.5 Leiomyosarcomas typically arise de novo rather than from preexisting leiomyomas.

Leiomyosarcomas present as solitary, enlarging lesions most commonly on the hair-bearing areas of lower extremities.17 They can exhibit a variety of colors and may be painful, pruritic, or paresthetic. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma usually presents as small (<2 cm), sometimes ulcerated nodules that are fixed to the epidermis. Subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas tend to be larger and are usually not associated with epidermal change. Some patients have multiple grouped lesions; in one series, four of seven such patients had a previous retroperitoneal leiomyosarcoma,18 highlighting the importance of ruling out metastases in patients with numerous superficial leiomyosarcomas.

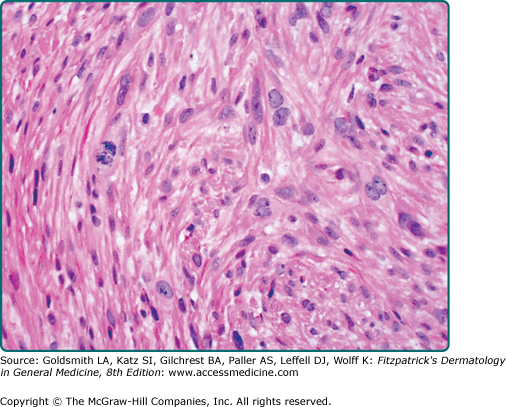

Leiomyosarcomas are large tumors consisting of smooth muscle fibers arranged in irregular, intersecting bundles and fascicles in the dermis and subcutis, often with infiltrating borders. Tumor cells exhibit smooth muscle differentiation with atypical cytologic features such as nuclear hyperchromasia, prominent nucleoli, mitosis, and necrosis (Fig. 127-3). In less well-differentiated areas, highly pleomorphic and multinucleated cells may be found.5 Granular cell, epithelioid cell, myxoid, and sclerosing (or desmoplastic) variants have been described.19 Leiomyosarcomas must be histopathologically distinguished from other malignant cutaneous spindle cell tumors, such as spindle cell melanoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, or atypical fibroxanthoma. Leiomyosarcomas stain positive with smooth-muscle actin, desmin, and vimentin and occasionally with S100 and cytokeratin, which makes distinguishing them from melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma difficult in certain cases.5,20,21

Differential diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma includes any solitary, enlarging dermal or subcutaneous nodule: lipoma, dermatofibroma, dermatofibrosarcoma, neurofibroma, spindle cell melanoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, and atypical fibroxanthoma.

The most important prognostic factor depends on whether the leiomyosarcoma is of cutaneous or subcutaneous origin. Although both cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions may recur locally in up to one-third to one-half of cases, the risk of metastasis is 5%–10% for cutaneous leiomyosarcomas compared with 30%–60% for subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas.5,9,16,17,22–25 The lung is the most common location of metastasis.

Therapy for superficial leiomyosarcoma is wide local excision with 3- to 5-cm margins and re-excision for recurrent lesions.17 On acral locations, complete excision may require amputation.17 Patients with subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas should undergo a chest X-ray for metastases. Adjuvant radiation and/or chemotherapy have unclear benefit. Alternative local treatment modalities in selected patients include Mohs micrographic surgery, cryosurgery, and isolated limb perfusion with chemotherapeutic agents.17,26

|

First described by Stokes in 1923,27 smooth muscle hamartoma has become increasingly recognized during the last two decades. Most cases are congenital but some are acquired,28,29 and prevalence estimates of up to 0.2% in children have been reported.29

Smooth muscle hamartoma is a benign proliferation of mature smooth muscle. The cause is unknown, and the majority of cases are present from birth.

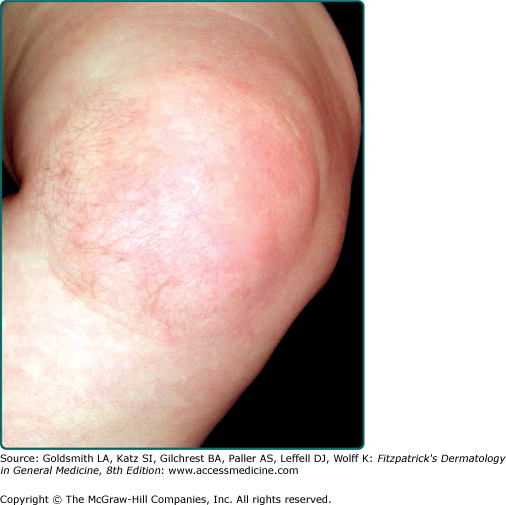

Smooth muscle hamartoma is usually found on the trunk or extremity (Fig. 127-4) and may take one of several forms: a single patch or plaque with or without follicular prominence, grouped solitary lesions (rarely with a linear distribution), and diffuse skin involvement as seen in the Michelin tire baby syndrome.30,31 Lesions can exhibit variable hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis. Vellus hairs may be prominent. Some can produce worm-like movements (vermiculation), and stroking may induce transient induration with piloerection (pseudo-Darier sign). Smooth muscle hamartoma shares some clinical and histologic features with Becker’s nevus. Some authors consider these lesions a spectrum,29 whereas others prefer to keep them separate.28,32

There is a marked increase of sharply circumscribed bundles of smooth muscle fibers that are haphazardly arranged in the reticular dermis. These fibers are sometimes associated with follicular units. There may be basal layer hyperpigmentation, as well as acanthosis and papillomatosis of the overlying epidermis. Factors that help to distinguish smooth muscle hamartomas from pilar leiomyomas include the grouping of smooth muscle fibers into discrete bundles and the lack of intermingling of these bundles with dermal collagen fibers.

Differential diagnosis of hamartoma includes congenital nevus, Becker’s nevus, café-au-lait macule, leiomyoma, neurofibroma, and solitary mastocytoma.

Malignant degeneration has not been reported. Although the localized form is usually not associated with other congenital anomalies,29 patients with the generalized form have been reported to have multiple associated congenital malformations33 and psychomotor retardation.33,34

No specific treatment is indicated. Surgical excision can be performed if the lesions are of cosmetic concern.

Tumors of Striated Muscle

Tumors of striated muscle include true neoplasms of striated muscle differentiation (rhabdomyomas and rhabdomyosarcomas) as well as non-neoplastic neuromuscular and rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartomas (RMHs).

|

Extracardiac rhabdomyomas are extremely rare and comprise fewer than 2% of striated muscle neoplasms.35 The adult and fetal types of rhabdomyomas occur predominantly in male patients. Cardiac rhabdomyomas occur in approximately 30%–50% of patients with tuberous sclerosis (TS; see Chapter 140).36

Rhabdomyomas are benign tumors of striated muscle. Extracardiac rhabdomyomas are not associated with TS, whereas significant portion of patients with cardiac rhabdomyomas are ultimately diagnosed with TS.

Extracardiac rhabdomyomas are subdivided into three types: (1) adult, (2) fetal, and (3) genital.35,37 The designation as adult or fetal refers to the tumor’s resemblance to adult or fetal skeletal muscle, not to the age of the patient.37 Adult and fetal types usually arise in the soft tissues or mucosal surfaces of the head and neck region soon after birth. They are usually asymptomatic. The fetal type has been repeatedly associated with basal cell nevus syndrome.37 Genital rhabdomyomas usually occur as small polypoid vaginal or vulvar lesions in middle-aged women.37

Rhabdomyomas are composed of fascicles of oval and polygonal-shaped cells with eosinophilic, often vacuolar cytoplasm and eccentrically placed nuclei.35 Atypia, mitosis, and pleomorphism are absent.

Differential diagnosis of rhabdomyomas includes granular cell tumor (GCT), hibernoma, and reticulohistiocytoma.

Extracardiac and cardiac rhabdomyomas have a very low risk of malignant degeneration. Many cardiac rhabdomyomas regress spontaneously with age.

The treatment of choice for symptomatic extracardiac rhabdomyomas is surgical excision.

|

Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most frequent soft-tissue sarcoma of childhood with annual incidence of 4.3/million, accounting for approximately 50% of soft-tissue sarcomas in children younger than age 15 years and 5%–8% of all childhood cancers.38–40 Only approximately 0.7% occur as primary skin lesions.40 Males are more commonly affected than females.38

Rhabdomyosarcomas are malignant neoplasms derived from skeletal muscle precursors. Primary cutaneous disease is rare, and skin involvement is more commonly a result of either direct extension from underlying soft tissues or metastases.41 Four subtypes have been described based on histologic appearance: (1) embryonal, (2) alveolar, (3) botryoid, and (4) pleomorphic. The embryonal type is most common, followed by alveolar. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma is characterized at the molecular level by novel fusion genes combining the forkhead (FKHR) gene with either the PAX3 or the PAX7 gene, producing a t(2;13)(q35;q14) or t(1;13)(p36;q14), respectively.38

Cutaneous rhabdomyosarcoma typically presents as an enlarging subcutaneous or ulcerated tumor involving the head and neck, the genitourinary tract, or the extremities. A deep soft-tissue rhabdomyosarcoma can also extend into the overlying skin and present as a cutaneous nodule.40 In neonates, congenital alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma is a very rare cause of “blueberry muffin baby” in which multiple cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases present as scattered blue nodules.

Rhabdomyosarcoma is composed of sheets of pleomorphic, small blue cells infiltrating the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. High mitotic index is present, and focal areas of necrosis can often be identified.41 The embryonic type is composed of interlocking bands of spindle cells and sheets of small round cells whereas the alveolar type exhibits loss of cellular cohesion leading to spaces resembling alveoli. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in differentiating rhabdomyosarcoma from other “small blue cell tumors.” Rhabdomyosarcomas express positivity for muscle-specific actin, desmin, myoD1, and myogenin. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis can used to detect the t(2;13)(q35;q14) and t(1;13)(p36;q14) chromosomal translocations.38,41

Differential diagnosis of rhabdomyosarcoma includes hemangioma, hematoma, neuroblastoma, and other soft-tissue sarcomas.

Prognosis is poor, with many patients succumbing to their disease. Even with appropriate treatment, rhabdomyosarcomas can recur and metastasize to regional lymph nodes, lung, bone, and heart. Congenital alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma has an especially poor prognosis; there are no reports in the literature of survivors.38

Treatment of rhabdomyosarcoma consists of a combination of surgical excision, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.

![]() Neuromuscular hamartoma is a very rare entity of which fewer than 20 cases have been reported in the English-language literature 42; it is also known as neuromuscular choristoma or benign triton tumor. Histologically, the lesion is composed of intermingling bundles of benign-appearing nerves fascicles and mature skeletal muscle fibers. In some cases, muscle fibers actually grow within the nerve fascicles. Most reported cases involved large deep nerves, and cutaneous involvement is rare.

Neuromuscular hamartoma is a very rare entity of which fewer than 20 cases have been reported in the English-language literature 42; it is also known as neuromuscular choristoma or benign triton tumor. Histologically, the lesion is composed of intermingling bundles of benign-appearing nerves fascicles and mature skeletal muscle fibers. In some cases, muscle fibers actually grow within the nerve fascicles. Most reported cases involved large deep nerves, and cutaneous involvement is rare.

![]() Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma (RMH) is a rare entity; only about two dozen cases have been described.43 It is also known as striated muscle hamartoma, hamartoma of cutaneous adnexa and mesenchyma, or congenital midline hamartoma. It presents as a pedunculated nodule (skin tag), usually on the face around the eyes, nose, or mouth. Most are solitary; rare patients with multiple lesions have been described. Although most are congenital, a few have been noted only in adults. Histologically, the dermis contains randomly oriented, mature, striated muscle fibers admixed with mesenchymal elements (adipose tissue, vessels, and collagen) and prominent nerves. Skin appendages are also prominent. Excision is usually curative. RMH has been associated with both ocular and central nervous system anomalies. Some patients with RMH and multiple associated malformations fulfill the criteria for Delleman oculocerebrocutaneous syndrome or Goldenhar’s oculoauriculovertebral syndrome. A diagnosis of RMH should prompt further investigation, especially to rule out cerebral malformations.

Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma (RMH) is a rare entity; only about two dozen cases have been described.43 It is also known as striated muscle hamartoma, hamartoma of cutaneous adnexa and mesenchyma, or congenital midline hamartoma. It presents as a pedunculated nodule (skin tag), usually on the face around the eyes, nose, or mouth. Most are solitary; rare patients with multiple lesions have been described. Although most are congenital, a few have been noted only in adults. Histologically, the dermis contains randomly oriented, mature, striated muscle fibers admixed with mesenchymal elements (adipose tissue, vessels, and collagen) and prominent nerves. Skin appendages are also prominent. Excision is usually curative. RMH has been associated with both ocular and central nervous system anomalies. Some patients with RMH and multiple associated malformations fulfill the criteria for Delleman oculocerebrocutaneous syndrome or Goldenhar’s oculoauriculovertebral syndrome. A diagnosis of RMH should prompt further investigation, especially to rule out cerebral malformations.

Benign Proliferations of Nerves: Neuromas

|

The exact incidence of traumatic neuromas is not known. Several small studies suggest that up to 30% of amputations result in neuromas.44,45

When a nerve is partially or completely severed, axons and Schwann cells can proliferate from the proximal stump and form a disorganized tangle of nerves and fibroblasts, called a traumatic neuroma. Within the bundle of nerves and fibroblasts, the axons can begin to synapse and send pain signals. These signals occur spontaneously or after mechanical thresholds lower than in normal nerves. The nerve proliferation typical of accessory digits may also represent an example of traumatic neuroma.

Traumatic neuromas are flesh-colored papules or nodules occurring at the sites of previous trauma or surgery. They often occur within suture lines and can be very painful.

Histologically, a neuroma appears as a collection of nerve fascicles that are haphazardly arranged. A fibrous or collagen sheath may surround neuromas, but these neuromas are not encapsulated by perineurium. The neuromas stain for EMA. Staining of the neural lesions is reviewed in Table 127-1.

Neural Proliferation | S100 | Neurofilament | Epithelial Membrane Antigen (EMA) | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Traumatic neuroma | + | + | + | Neuron-specific enolase positive |

Palisaded encapsulated neuroma | + | + | + for the capsule | |

Schwannoma | + | − | + for the capsule only | Vimentin positive |

Neurofibroma | + | Variable | − | |

Plexiform neurofibroma | + | + | ||

Neurothekeoma | +/− | − | Variable | Vimentin variable; usually EMA negative |

Cellular neurothekeoma | − | − | CD57 positive; Ki-Mip positive | |

Perineurioma | − | − | + | Vimentin positive; neuron-specific enolase negative |

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | + | + | Variable | Vimentin variable; cytokeratin negative; neuron-specific enolase positive |

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor | + if differentiated | Neuron-specific enolase positive; CD99 positive | ||

Granular cell tumor | + | Neuron-specific enolase positive |

Differential diagnosis of neuromas includes hypertrophic scar, dermatofibroma, digital fibrokeratoma, and verruca vulgaris.

Temporary pain relief can be achieved with a local anesthetic nerve block. For more permanent pain relief, surgical treatment aims either at isolating the nerve from injury or excising the neuroma.46

Palisaded encapsulated neuromas (PENs) present in adults, mostly in their third to fifth decade. There appears to be no gender predilection. PENs make up approximately one-fourth of benign cutaneous neural lesions.47

PENs consist of a hamartomatous overgrowth of Schwann cells.48 The etiology is unknown.

PENs often present as asymptomatic, flesh-colored papules or nodules that are smaller than 1 cm in diameter. PENs are located on the face in approximately 80% of cases.47 PEN is almost never diagnosed clinically; the most common misdiagnoses are dermal melanocytic nevus, basal cell carcinoma, and adnexal tumor.

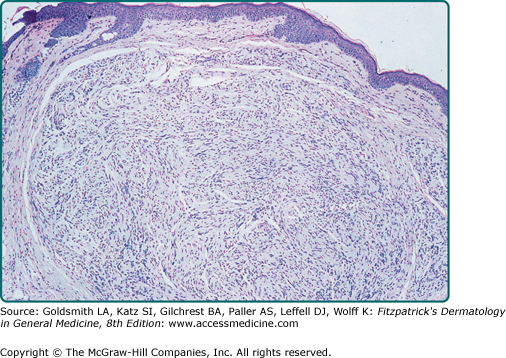

PENs are well-demarcated dermal nodules composed of fascicles of Schwann cells (Fig. 127-5). Contrary to what the name implies, the capsule is rarely complete and the palisading typical of schwannomas is often indistinct. Special stains demonstrate variable numbers of axons within the lesion. The capsule often stains with EMA, suggesting a perineural origin, and the tumor body stains for S100, suggesting a Schwann cell origin (see Table 127-1).49,50 Some PENs may actually be small dermal schwannomas that contain a few residual entrapped axons.51

Figure 127-5

Histologic appearance of a typical palisaded encapsulated neuroma. The tumor is composed of fascicles of Schwann cells and surrounded by a delicate capsule best seen on the left. There is a suggestion of nuclear palisading, but this is not as pronounced as that seen in a schwannoma. (The axons that are normally also present cannot be seen on this stain; hematoxylin and eosin, ×40.)

Differential diagnosis of PEN includes dermal melanocytic nevus, basal cell carcinoma, adnexal tumor, and neurofibroma.

Excision is the treatment of choice. There is no evidence of an association between PEN and neurofibromatosis (NF; see Chapter 141) or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2B (MEN2B; see Section “Mucosal Neuromas and Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Syndrome Type 2B”).

Due to inconsistent nomenclature, the incidence of mucosal neuromas is not known.52

MEN2B is an autosomal dominant condition. MEN2B is caused by germ-line mutations of the RET

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree