13 Neck rejuvenation

Synopsis

Aging affects the face globally. Therefore, the neck is an important component of any facelift procedure.

Aging affects the face globally. Therefore, the neck is an important component of any facelift procedure.

Improvement in neck contour is predicated upon skin release from retaining ligaments, appropriate removal of fat from the subcutaneous and subplatysmal plane and alteration of the medial platysma.

Improvement in neck contour is predicated upon skin release from retaining ligaments, appropriate removal of fat from the subcutaneous and subplatysmal plane and alteration of the medial platysma.

In selected instances, the neck can be treated as an isolated entity including submental approach only (anterior lipectomy and platysmaplasty) and direct excision of neck skin.

In selected instances, the neck can be treated as an isolated entity including submental approach only (anterior lipectomy and platysmaplasty) and direct excision of neck skin.

For best results, skeletal developmental abnormalities are treated at the time of face/necklift.

For best results, skeletal developmental abnormalities are treated at the time of face/necklift.

History

1978 Connell – Contouring the neck by lipectomy and a muscle sling

1979 Aston – The platysma muscle in rhytidoplasty

1980 de Castro – The anatomy of the platysma muscle

1980 Ellenbogen and Karlin – Visual criteria for restoring the youthful neck

1985 Courtiss – Suction lipectomy of the neck

1989 Furnas – The retaining ligaments of the cheek

1990 Feldman – Corset platysmaplasty

1991 De Pina and Quinta – Aesthetic resection of the submandibular gland

1992 Hamra – Deep plane rhytidectomy

1995 Giampapa and Di Bernardo – Neck recontouring with suture suspension and liposuction

1996 Biggs – Excision of neck redundancy with single Z-plasty closure

1998 Knize – Limited incision submental lipectomy and platysmaplasty

1997 Connell and Shamoun – The significance of digastric muscle contouring

1997/2001 Baker – Short scar facelift

2002 Tonnard – Minimal access cranial suspension (MACS) lift

2005 Zins and Fardo – The anterior only approach to neck rejuvenation

2006 Sullivan et al. – Neck contouring with submandibular gland suspension

Anatomy and the effect of aging

The critical anatomical areas in the neck are the cervicomental angle, the submental/submandibular triangles and the gonial angles. The paired anterior bellies of the digastric muscles extend from the lesser cornu of the hyoid bone to the posterior surface of the mandible on each side of the symphysis. The motor innervation of the anterior belly of the digastric muscle is the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. The muscles act as weak depressors of the mandible. Excision produces no noticeable functional deficit but does cause retro-positioning of the hyoid bone and, therefore, a favorable deepening of the cervicomental angle.1

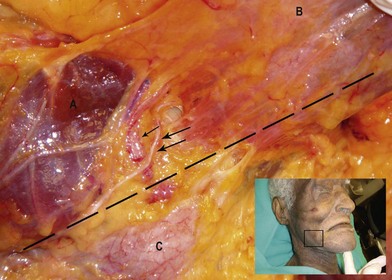

In the lower face, the marginal mandibular nerve exits from under the anterior-inferior portion of the parotid gland. In this location the course is deep to the parotid masseteric fascia. It runs horizontally along the lower border of the mandible passing from deep to the parotid masseteric fascia into the subSMAS cleavage plane and continuing superficial to the facial vessels to innervate the depressor anguli oris and mentalis muscles.2 This is the area most prone to marginal mandibular nerve injury during facelift surgery (Fig. 13.1). Both the lingual and hypoglossal nerves lie deep to the submandibular gland. Therefore, intracapsular resection of the gland minimizes the risk of bleeding and nerve injury.

Three important planes exist in the neck: the superficial plane between the skin and the platysma; the intermediate plane composed of the platysma and the interplatysmal fat; and the deep plane containing the subplatysmal fat, the anterior belly of the digastric muscles and the submandibular glands.3

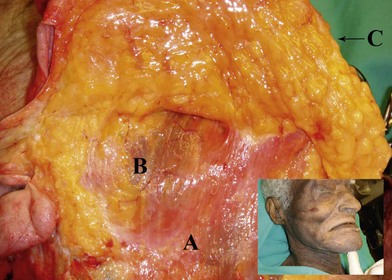

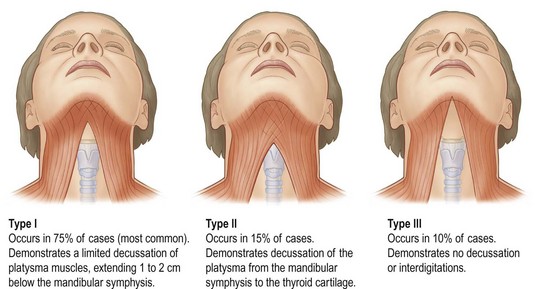

The platysma muscles are thin, bilateral structures that are continuous with the SMAS in the face.4,5 The platysma is vertically oriented in the neck extending from the clavicles inferiorly and predominantly horizontal in the lower face (Fig. 13.2). The platysma has osseous connections to the mandible as it ascends over the mandibular border. And while separate, the platysma is intimately related to the mandibular septum, both structures sending fibers to the mandibular border.6 Reece et al. recently described the mandibular septum. They suggest that the septum may act as a sling impeding fat descent below the mandible and hence lead to jowl formation.6 Because the platysma is continuous with the SMAS and has minimal bone contact, laxity in the SMAS is transmitted to the neck.2,4,5,7 There are three variations of platysmal anatomy in the submental region:

Type II (15%)

Interdigitation of the platysma muscles from the mandibular symphysis to the thyroid cartilage.

Type III (10%)

No interdigitation of the platysma muscles (Fig. 13.3).8

In addition to skin quality, soft tissue laxity and fat maldistribution, developmental variations of the bony anatomy, will have a decided effect on the aging process. Specifically, sagittal and vertical microgenia and/or a skeletal Class II appearance will have a negative impact on support of the lower face and neck. Similarly an obtuse gonial angle or mandibular plane will negatively affect lower facial aging. Conversely, correction of these skeletal deformities will have a decidedly positive effect on the facial aging process (Fig. 13.4).

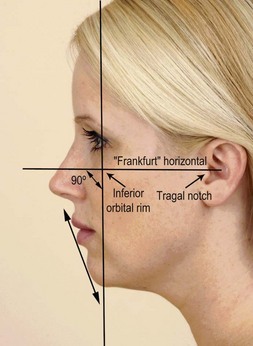

The hallmark of a youthful face is a well-contoured neck.9–12 Several criteria of a youthful neck have been defined including a curving or blunt cervicomental angle of 105–120°, a distinct inferior mandibular border, a slightly visible thyroid cartilage and a visible anterior sternocleidomastoid border (Fig. 13.5).13,14 Knize grades the degree of neck deformity on a I–IV scale. Grade I represents an ideal neck angle and increasing numbers indicate increasing deformity. Using this system, he documented consistent and significant long-term neck correction following anterior lipectomy and platysmaplasty.15,16 It is important to note, however, that an isolated necklift in the presence of significant jowling and descent of the neck–face junction will generally not produce a pleasing aesthetic result.3

Effects of aging/disease process

Aging in the lower face is due to varying degrees of laxity which develops in the skin, retinaculum cutis and cutaneous ligaments of the face. Which component is most responsible for facial aging dictates the type of face/necklift procedure chosen. The importance of laxity in the lower masseteric cutaneous ligaments as a major factor in the development of the jowl has been established for some time.17 More recently, this anatomy and its implications for aging have been further clarified by Mendelson.2 This information is thoroughly reviewed in Chapter 6. Mendelson’s “premasseteric space” overlies the lower one-half of the masseteric muscle. The roof of the space is the platysma, the posterior border of the masseter represents its posterior border, the inferior border of the mandible and mandibular septum its inferior border, the anterior border of the masseter and the lower masseteric-cutaneous ligaments its anterior border. Superiorly are the stout upper masseteric-cutaneous ligaments. This is a potential space in youth, but becomes a true space with facial aging, expanding and bulging onto the masseteric ligaments. This results in stretching and jowl formation.

In Chapter 11, facelift techniques are reviewed and authors present their preferred method to manipulate the deeper soft tissues of the face. Conceptually, techniques which involve the SMAS are based on the premise that a major component of facial aging is due to laxity in the SMAS and the cutaneous ligaments. Not only do the SMAS procedures correct this laxity, but the SMAS also acts as a vehicle for repositioning lower face and submental fat. Whether SMAS plication,18 SMAS excision and closure (lateral SMASectomy)19 or ligament release, SMAS advancement and reattachment (extended SMAS procedures)9–12,20–23 is superior, is open to question. Furthermore, certain techniques favor a vertical advancement of the SMAS,9–11,20–26 while others utilize an oblique vector.18,19

In Chapter 11, the MACS lift principle, originally described by Tonnard, was reviewed. In that technique, platysma tightening is accomplished along a mostly vertical vector utilizing purse-string sutures in the cheek. Fogli borrows on and extends this concept by relying on posterior-superior traction on the neck platysma rather than anterior (medial) platysma tightening. He believes that it is counterproductive to separate skin from platysma. He addresses the platysma with a vertically oblique vector, to Lore’s fascia (platysma auricular fascia, or parotid cutaneous ligaments). Higher in the cheek, he utilizes oblique vectors, suturing submalar fat to the malar bone and a running suture continues as an oblique vector ending at the anterior parotid fascia. His technique is predicated on the concept of addressing laxity where the laxity is greatest. Lax SMAS is sutured to immobile areas such as the malar bone and parotid fascia.7

While soft tissue changes associated with facial aging have received widespread attention, the effect of facial aging on the bony skeleton has not. Aside from the clear adverse effect of tooth loss on the lower vertical facial height on the maxilla and mandible, bony changes associated with facial aging have been limited to the correction of developmental abnormalities of the cheek and chin and infraorbital rim.27–30 However, certain dicta described in the orthognathic surgery literature should be applied to the aging lower face and neck.27,31–34 Rosen has demonstrated that just as expansion of the soft tissue envelope is desirable in the patient with facial aging, expansion of the bony envelope with augmentation techniques should be favored over reduction procedures in the aging face even when taken beyond normal cephalometric bounds.35,36

Horizontal advancement genioplasty tightens suprahyoid musculature, expands the skin envelope and improves the profile (Fig. 13.6), while chin reduction procedures lead to a relative excess of the skin envelope, chin ptosis and an adverse effect on the profile with aging.

Preoperative assessment

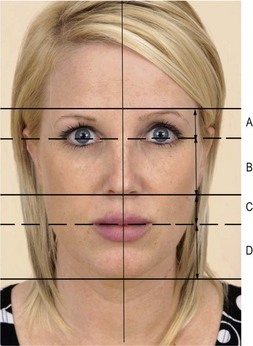

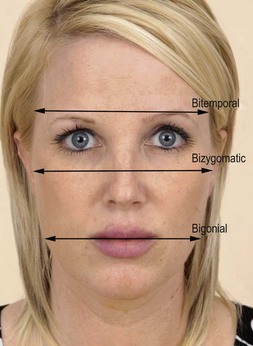

An analysis of facial proportions on the patient with facial aging is a good starting point for patient assessment from both a diagnostic and treatment standpoint. This can be done rapidly during the patient examination in the office, as well as from patient photographs after the initial interview. There are a number of good methods of both frontal and profile assessment. The analysis in Figure 13.7 depicts ideal frontal facial proportions, Figure 13.8, the ideal transverse and, Figure 13.9, the ideal proportions in profile. Facial aging is exacerbated by deficiencies in lower vertical facial height (Fig. 13.10) and by lower face sagittal deficiencies (Fig. 13.4). Vertical deficiency in the frontal plane is corrected at the time of facelift/necklift surgery by vertical lengthening genioplasty. Sagittal microgenia is corrected by horizontal genioplasty or alloplastic chin augmentation (Figs 13.4 and 13.6, respectively).

Fig. 13.10 (A) Preoperative frontal view demonstrates less than ideal facial proportions with eyebrow height significantly less than the vertical height of the upper lip (see Fig. 13.6). (B) The patient also demonstrates ptosis of the chin in preoperative profile view. (C) A 6-year postoperative frontal view demonstrates maintenance of corrected brow position following endoscopic browlift and extended SMAS facelift surgery. (D) A 6-year postoperative profile view demonstrates maintenance of soft tissue chin correction.

Midface weakness in the pyriform aperture area or the submalar area results in premature aging, deepening of the nasolabial folds and a relative excess of the soft tissue envelope. Expansion of the soft tissue envelope by soft tissue augmentation with fat injection or with a submalar implant has a beneficial effect on facial aging (Fig. 13.11).

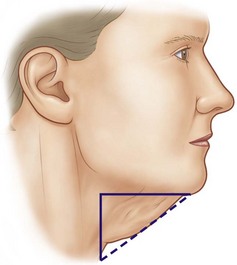

An attractive gonial angle may be masked by the fatty neck. Conversely defatting just posterior to the ramus of the mandible and inferior to the gonial angle will define and enhance the lower face. When defatting is combined with SMAS tightening the surgical result is significantly enhanced (Fig. 13.12).

In evaluating the neck proper, aging in the neck may be due to skin excess, fat accumulation, platysma laxity, digastric, submandibular gland abnormalities or anatomic variants such as a low hyoid bone (i.e., abnormalities in the superficial, intermediate or deep planes).3 Evaluation of the skin is relatively straightforward. Marked laxity or excess skin dictates the need for a pre and postauricular incision for proper skin redraping. Mild to moderate skin laxity may be treated by a short-scar facelift approach or submental incision and skin undermining through the submental approach. Numerous authors have stated that skin often need not be removed from the neck during face/neck rejuvenation.13–16,27,28,37–46 This is due to: (1) the unique ability of neck skin to contract once released from the platysma and (2) more, not less skin, is needed once the obtuse angle of the neck becomes more acute, i.e., the hypotenuse of a triangle is less than its two sides (Fig. 13.13).

Nonsurgical options

Some nonsurgical treatments have been advocated for neck rejuvenation. These include botulinum toxin,47 injectable fillers,48,49 lasers50 and intense pulse light.51 Although these alternatives have a role in the treatment of facial aging either as ancillary or stand-alone procedures, they do not exert the same impact on facial aging that is seen with face/necklift surgery.

Minimally invasive options

Threadlift in facial rejuvenation

A variety of internal sutures, anchored barbed sutures and threadlift techniques have been introduced as minimally invasive alternatives to traditional facelift surgery. These varieties include the Contour Threads (Surgical Specialties Corp., Reading, PA), the APTOS Threads (APTOS, Moscow, Russia) and the Isse Endo Progressive Facelift suture.52–54

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree