Neck

Introduction

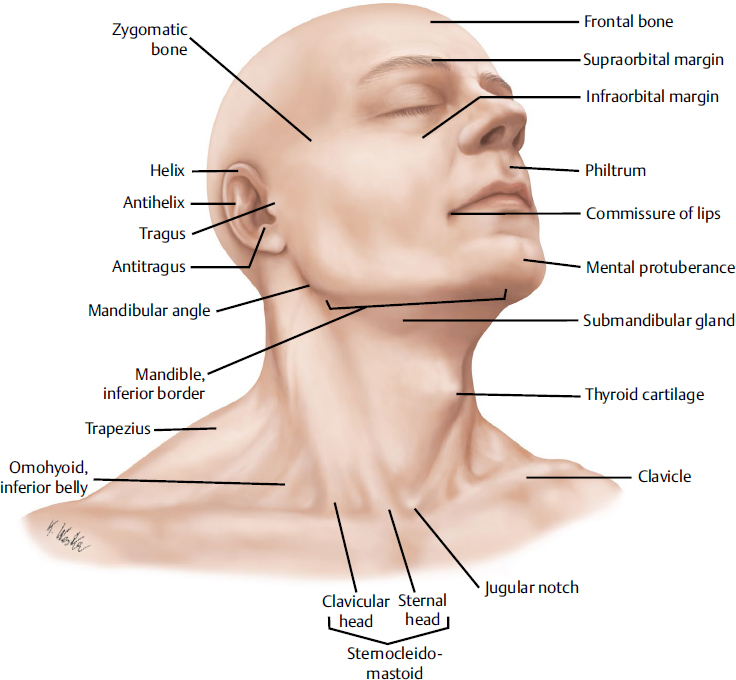

The neck is a cylindrical structure that extends from the base of the skull to the thoracic inlet (Fig. 21.1). The neck encloses many vital structures and acts as a conduit between the cranium superiorly and the thorax and upper limb inferiorly. Anatomically, the neck is organized into three basic compartments:

• Posterior compartment: musculoskeletal (support and movement of the head and neck)

• Anterior compartment: visceral (glandular, respiratory, and gastrointestinal)

• Lateral compartment: large blood vessels and nerves

Skeletal Support

Cervical Spine

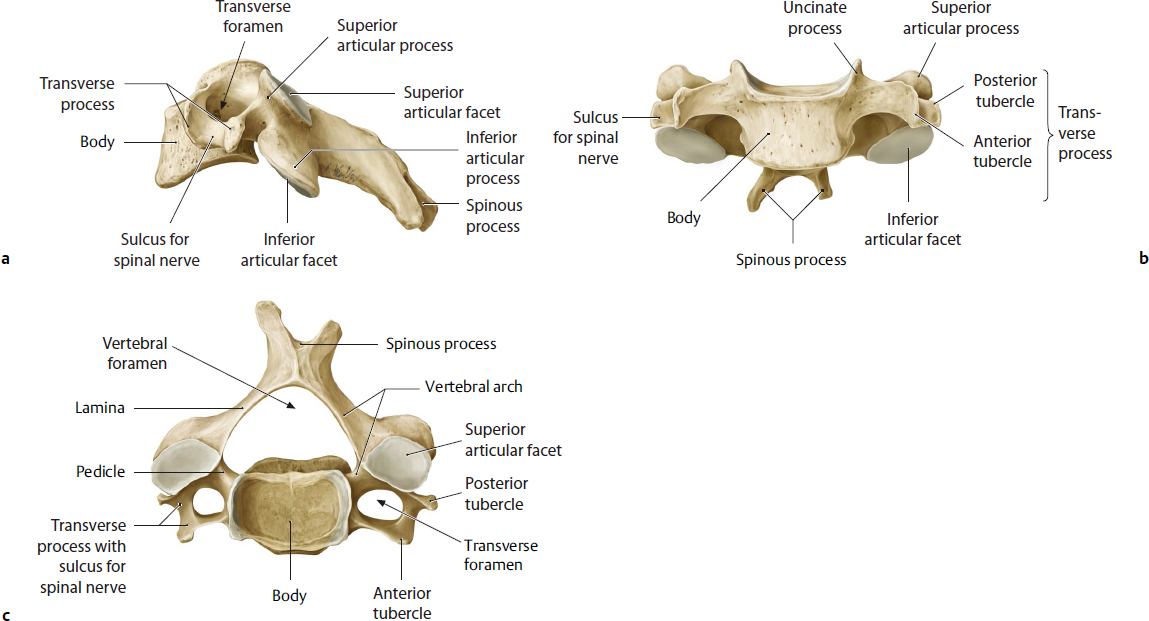

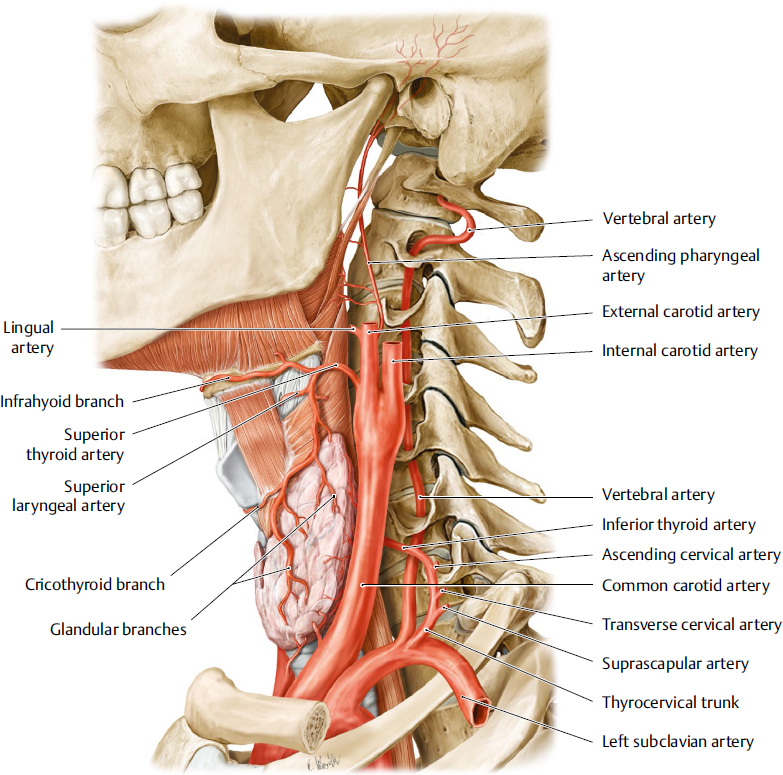

The cervical spine consists of seven vertebrae with some common characteristics and specific features for C1, C2, and C7 (Fig. 21.2). In the cervical region, the bodies of the vertebrae are relatively small, and wider transversely than anteroposteriorly, the pedicles are directed laterally and posteriorly, and the laminae are relatively narrow. The transverse processes are pierced by foramen transversaria, through which pass the vertebral artery from usually C1 to C6 vertebrae (Fig. 21.3).

The atlas (C1) is the uppermost of the vertebrae; it articulates with the base of the skull and allows anteroposterior movement. It does not have a vertebral body. The axis (C2) is the second vertebra and articulates with the atlas as a pivot that allows rotation. It has a characteristic odontoid process, rising perpendicular from the superior surface of the body. A strong transverse ligament completes the articulation between the atlas and the odontoid process posteriorly. C7 is known as the vertebra prominens and has a characteristic prominent spinous process that can be palpated; it represents the external landmark for the lower part of the cervical spine. In some individuals, C7 is associated with an abnormal extra rib (cervical rib), which can produce symptoms of compression of blood vessels at the root of the neck or of the brachial plexus. When symptomatic, it is referred to as thoracic outlet syndrome.

Surgical Annotation

In a number of genetic syndromes, including Down’s syndrome, after infections of the spine and in patients with a history of rheumatoid arthritis, the atlantoaxial joint can be unstable, and in hyperextension, it leads to compression of the spine, which may be fatal. Patients who have a history of rheumatoid or predisposing genetic syndromes are at greater risk for a general anesthetic as a result of the need to hyperextend the neck during intubation.

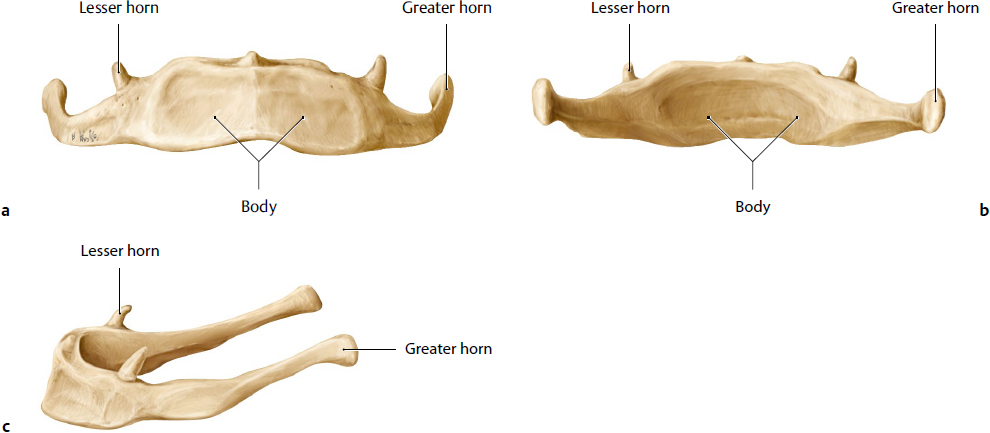

Hyoid Bone

The hyoid takes support only from the muscles and ligaments associated with mobility of the gastroesophageal and respiratory visceral structures in the neck and floor of mouth (Fig. 21.4). The bone has a U-shape contour and is divided into three com ponents: the body, positioned anterior and horizontally, and laterally paired projections, the greater and lesser horns or cornua. The greater horns project posteriorly and superiorly, and the lesser horns project superiorly. The hyoid bone provides attachment to muscles that move the tongue, depresses the mandible, and moves the larynx. The superior attachments are for the middle pharyngeal constrictor, hyoglossus, mylohyoid, geniohyoid, stylohyoid, and digastric muscles. The inferior attachments are for the thyrohyoid, stylohyoid, and omohyoid muscles.

Skin, Adipose Tissue, Fascia

Skin

The skin on the neck is thin and drapes along the contour of the deeper structures anteriorly. The skin on the posterior neck has thicker dermis, with stronger stabilizing fibrous septae, and has limited mobility. In the submental and submandibular areas, the skin is less adherent. In the postauricular and mastoid regions, it is closely attached to the underlying tissues.

Adipose Tissue

The adipose tissue in the neck is distributed in the supraplatysmal, interplatysmal, and subplatysmal planes (Fig. 21.5). The anatomical studies reveal that the fat in the subcutaneous plane ranges from 8.4 to 15 g (Fig. 21.5a). The total amount of fat in this region can vary in the presence of weight excess. The fat in the subplatysmal plane averages 3.7 g (Fig. 21.5b). In clinical settings, it appears to be less influenced by weight variations. The fat is compartmentalized in the submental region.1–3

Fig. 21.2 Typical cervical vertebra (C4). (a) Left lateral view. (b) Anterior view. (c) Superior view. (From THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, General Anatomy and Musculoskeltal System. © Thieme 2005, Illustrations by Karl Wesker.)

Fig. 21.4 The hyoid bone. (a) Anterior view. (b) Posterior view. (c) Left lateral view. (From THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, General Anatomy and Musculoskeltal System. © Thieme 2005, Illustrations by Karl Wesker.)

Surgical Annotation

The volume of the neck is determined by the extent of fat deposition, which in turn determines the girth of the neck. In the fatty neck, there is fat deposition in the superficial and the deeper layers, generating a less defined or even convex shape of the cervicomental angle. Volume reduction during neck contouring can incorporate volume reduction in all fat compartments of the anterior neck to reduce girth and to improve contours. In slim necks, there is minimal fat and the skin drapes over the platysma causing visible bands in older subjects.

Cervical Fascia

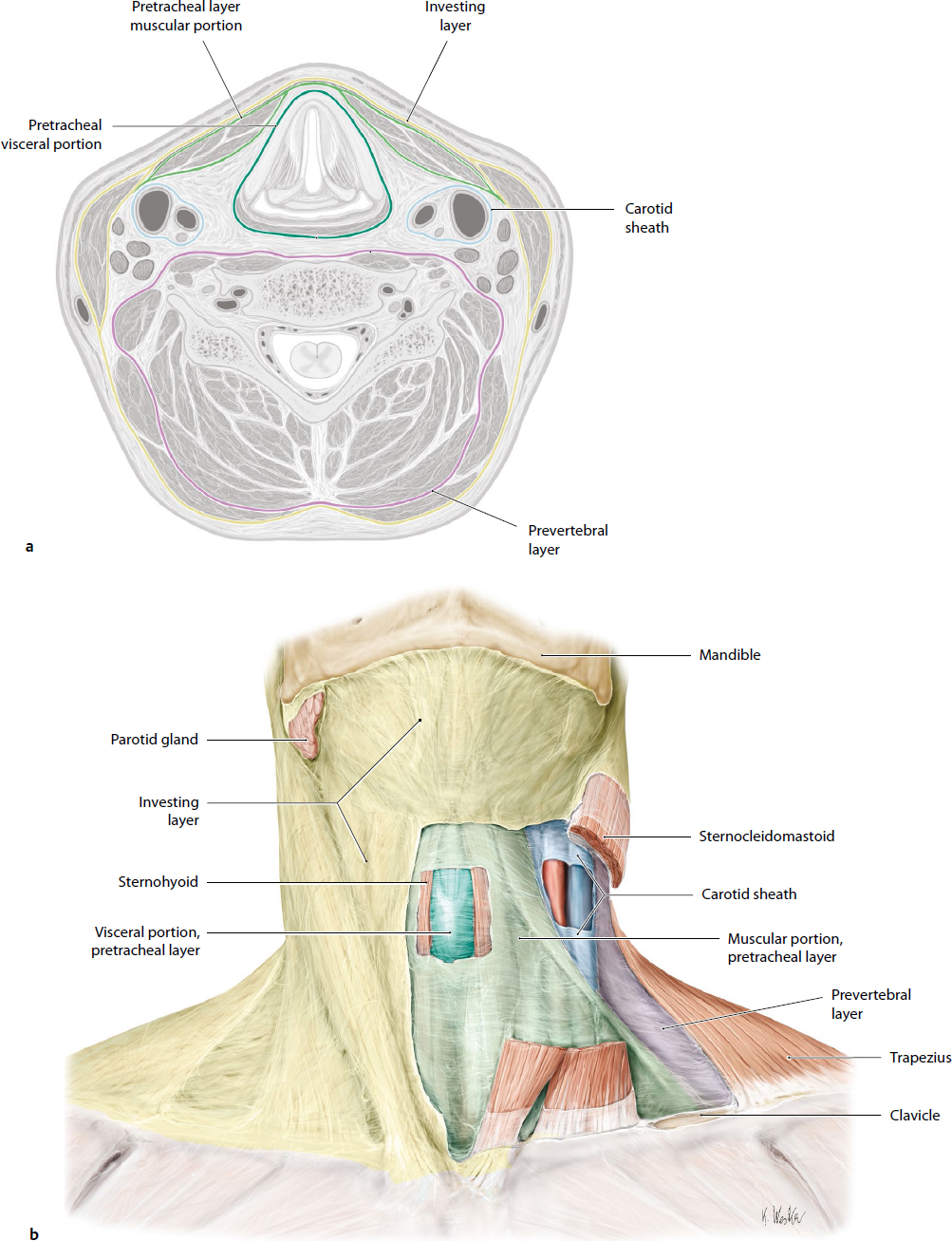

The cervical fascia is broadly divided into superficial and deep layers (Fig. 21.6).

Superficial Cervical Fascia

Superficial cervical fascia is the continuation of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS), also referred to as the SMAS layer. It contains cutaneous nerves, blood vessels, lymphatics, and variable amounts of fat. The platysma is found anterolaterally and is adherent to the skin via multiple connective tissues bands. It is a paired muscle found lateral to the midline.

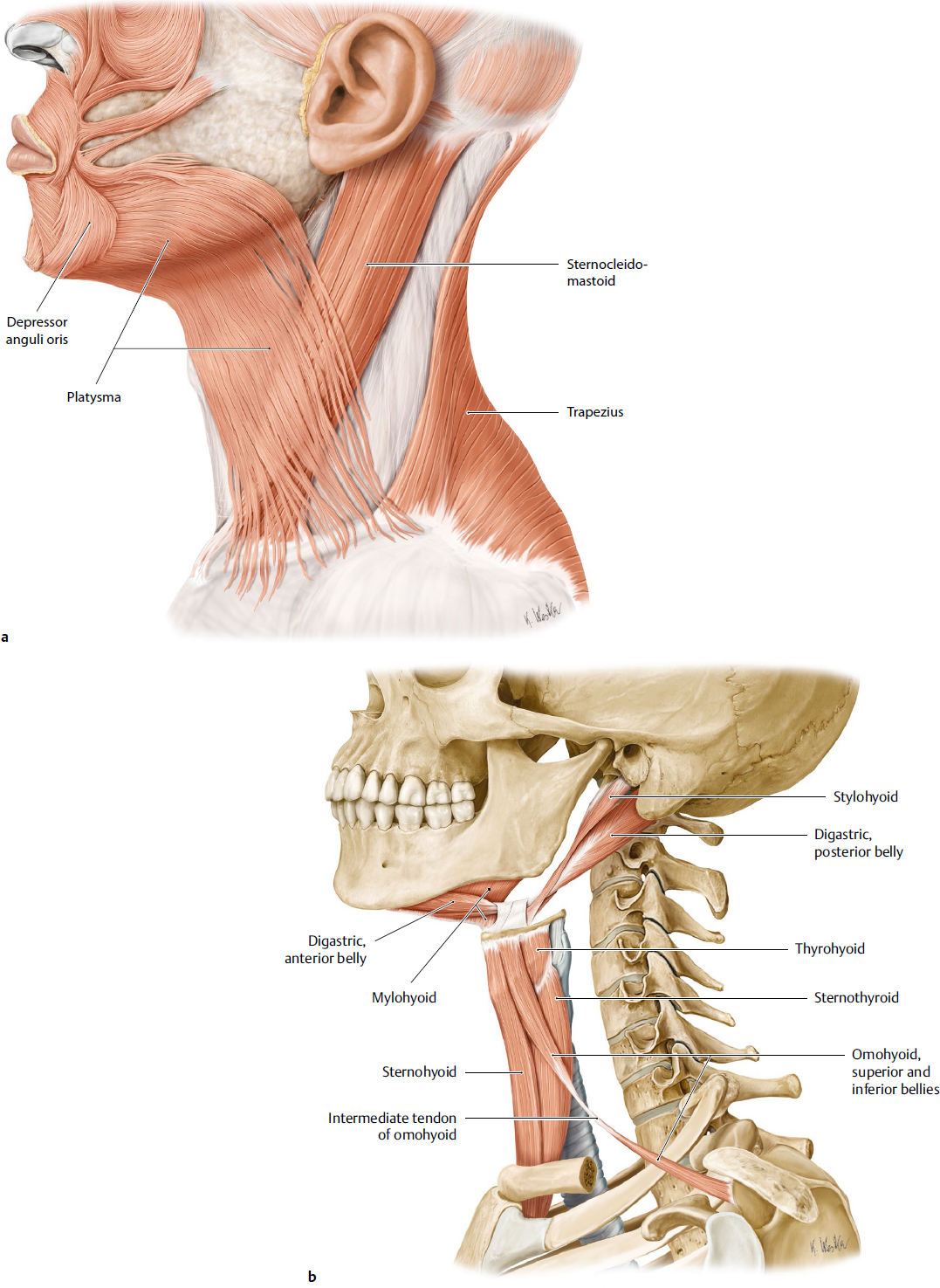

Platysma

The platysma muscle is a thin, wide superficial muscle, originating from the superficial fascia over the upper thorax (Fig. 21.7a). The muscle fibers fan out superiorly and inserted into the lower border of the mandible and skin and intermingle with the muscles of facial expression on the lower face. Its innervation is provided by the cervical branch of the facial nerve, and the blood supply is provided by the facial artery, superior thyroid artery, and branches of the posterior auricular and occipital arteries. Its main action in humans is as an accessory depressor of the oral commissure. The platysma muscle courses over the concave contours of the neck and does not have any retention ligaments or pulleys superficial to it. Its deep attachments, the cervical retaining ligaments, adherent to the superficial layer of the deep fascia, are responsible limiting the anterior displacement of the muscle belly during contraction. Later in life, the muscle is responsible for the appearance of vertical dynamic bands, labelled as platysma bands.

Surgical Annotation

The platysma is classified into three types, depending on the extent of decussation4:

• Type 1: Limited decussation of the platysma muscles, extending 1 to 2 cm below the mandibular symphysis (75%)

• Type 2: Decussation of the platysma from the mandibular symphysis to the thyroid cartilage (15%)

• Type 3: No decussation of the platysma muscles in the midline (10%)

Isolated platysmal bands associated with ageing can be successfully treated with neurotoxins. Correction of extensive laxity and divarication requires open procedures with interventions on the platysma muscles; plication, excision, and myotomy, and so forth.5–7 The superiorly and posteriorly based platysma muscle myocutaneous flaps are supplied primarily by the submental artery and secondarily by the superior thyroid, postauricular, and occipital arteries. The external jugular and submental veins provide the venous drainage. The platysma skin flap can be used to reconstruct defects in the orofacial region.8,9

Deep Cervical Fascia

The deep fascia can be divided into three layers: the investing layer of the deep cervical fascia, prevertebral fascia, and pretracheal fascia.

Investing Layer of the Deep Cervical Fascia

The investing layer completely encircles the neck and splits to enclose the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles. The investing layer of the deep cervical fascia is attached superiorly to the external occipital protuberance and superior nuchal line and inferiorly to the sternum, clavicle, and acromion of the scapula. The posterior attachments are on the spines of the cervical vertebrae and ligamentum nuchae, and the anterior attachments are on the mandibular midline, body of the hyoid, and manubrium sterni. The fascia splits to enclose the suprasternal space and the attachments of the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles.

In the mastoid region, the investing layer of the fascia is referred to as the parotid fascia, which splits into two layers to enclose the parotid gland. The parotid fascia is attached to the tip of the mastoid process, cartilaginous part of the external acoustic meatus, and lower border of the zygomatic arch. The deep layer extends along the base of the skull and merges with the carotid sheath. The fascia between the styloid process and the angle of the mandible forms the stylomandibular ligament.

Pretracheal Fascia

The pretracheal fascia extends from the hyoid to the thorax. The visceral layer envelops the trachea, esophagus, and thyroid gland and the muscular part encloses the infrathyroid muscles.

It is attached superiorly to the larynx, and inferiorly it extends along the superior mediastinum and merges with the fibrous pericardium.

Prevertebral Fascia

The prevetebral fascia encloses the cervical spine and the prevetebral and postvertebral muscles. It also forms the floor of the posterior triangle of the neck. The fascia extends superiorly to the skull base in front of the longus capitis and rectus capitis lateralis muscles and inferiorly into the thorax, where it merges with the anterior longitudinal ligament of the third thoracic vertebra. The fascia inserts posteriorly on the transverse and spinous processes of the cervical vertebrae and ligamentum nuchae. Inferiorly, the fascia covers the scalene muscles and extends laterally as axillary sheath.

Carotid Sheath

The carotid sheath receives contributions from prevetebral and pretracheal fasciae. It encloses the carotid artery, vagus nerve, lymph nodes, and internal jugular vein. The attachments of the carotid sheath are superiorly to the skull base, and inferiorly the fascia merges with the connective tissue surrounding the aortic arch.

Attachments

• Superior: Base of the skull

• Inferior: The fascia merges with the connective tissue around the arch of the aorta

Surgical Annotation

The arrangements of the fascial layers of the neck determine the spread of infection in the neck. They form important barriers to infection; once infection is established, the fascial layers play a part in directing its spread. The infection may travel through paths of least resistance from one space to another. The investing layer limits the spread of superficial infection. Deeper infections can spread to the thorax and retropharyngeal spaces.10,11

Fig. 21.7 Neck muscles. (a) The platysma muscle. (b) The superficial and middle layers of the muscle in the neck. (c) The deep muscle layers of the neck. (From THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, General Anatomy and Musculoskeltal System. ©Thieme 2005, Illustrations by Karl Wesker.)

Muscular Anatomy

Lateral Compartment

Sternocleidomastoid

This muscle is an important landmark of the neck as it defines the triangles of the neck and is closely related to the deeper neurovascular structures (Fig. 21.7b):

• Origin: It arises from two heads, tendinous (sternal) head from the manubrium sterni and muscular (clavicular) head from the upper surface of the medial third of the clavicle.

• Insertion: The muscle passes upward and outward and is inserted onto the mastoid process and the superior nuchal line.

• Blood supply: The blood supply is through the superior thyroid, occipital, posterior auricular, and suprascapular arteries.

• Nerve supply: The spinal accessory nerve is the nerve supply.

The muscle is sacrificed in radical neck dissection along with other structures of the neck.

Surgical Annotation

In congenital unilateral hypoplasia of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the muscle belly is shortened and tight, leading to a condition called torticollis. If left untreated, it leads to progressive mandibular and facial asymmetry through the growth period.

Anterior Compartment

Strap Muscles of the Neck

• Superficial layer: Omohyoid, sternohyoid

• Deep layer: Sternothyroid, thyrohyoid

• Nerve supply: Ansa cervicalis, thyrohyoid by the first cervical nerve

• Blood supply: Superior thyroid and lingual arteries

The omohyoid has superior and inferior bellies that are joined by an intermediate tendon. The superior belly is attached to the hyoid bone, and the inferior belly is attached to the scapula. The intermediate tendon is attached to the clavicle and first rib. The omohyoid depresses the hyoid bone from the elevated position. The sternohyoid and sternothyroid muscles originate from the posterior surface of the manubrium sterni. Sternohyoid has additional attachment on the clavicle and is inserted into the inferior border of the body of the hyoid bone. The sternothyroid is attached to the oblique line of the thyroid cartilage. The thyrohyoid muscle arises from the oblique line of the thyroid cartilage and is attached to the body and grater horn of the hyoid. The strap muscles act on the hyoid bone and larynx and assist in swallowing. The digastric, stylohyoid, mylohyoid, geniohyoid, hyoglossus, and genioglossus are classified together as muscles of the floor of the mouth.

Digastric Muscle

The digastric muscle consists of two bellies: the anterior belly and the posterior belly. Both bellies are connected by an intermediate tendon anchored to the hyoid.

Posterior Belly

• Origin: The mastoid notch is posterior to the mastoid process.

• The posterior belly of the digastric muscle runs forward and downward and passes through the stylohyoid muscle.

• Insertion: Insertion is to the greater horn of the hyoid bone by a fibrous loop.

• Blood supply: The blood supply is through the posterior auricular and occipital arteries.

• Nerve supply: The posterior belly is supplied by the facial nerve.

Anterior Belly

• Origin: The digastric fossa on the inferior border of the mandible is the origin.

• Insertion: The muscle runs downward and backward and is connected to the posterior belly via the intermediate tendon.

• Blood supply: Blood supply is through the submental branch of the fascial artery.

• Nerve supply: The mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve provides the nerve supply.

• Action: The digastric muscle helps to raise the hyoid bone and base of the tongue and assists in depressing and retracting the mandible.

Surgical Annotation

Excision of the anterior belly of digastric muscles is carried out as part of some neck dissections, as well as during some cosmetic interventions on the neck. The hypoglossal nerve courses deep to the anterior belly of the digastric muscle and mylohyoid muscles, transversely over the hypoglossus, and needs to be protected during surgery. Blunt dissection with hemostat clamps can be used to elevate the muscle belly from the underlying structures, and once the hypoglossal nerve has been visualized, superior and inferior transection of the muscle belly can be carried out safely.

Posterior Compartment

Posterior Neck Muscles: Trapezius

• Origin: External occipital protuberance, superior nuchal line, ligamentum nuchae, and the spine of the seventh cervical vertebra and spines of the all the thoracic vertebrae.

• Insertion: Spine and acromion of the scapula, lateral third of the clavicle

• Nerve supply: Accessory nerve, cervical plexus

• Blood supply: Superficial cervical, transverse cervical arteries

• Action: Elevates, rotates, and retracts the scapula with other muscles. When scapula is fixed, the trapezius moves the head backward and lateral.

Surgical Annotation

The trapezius myocutaneous flap is used for most of the head and neck reconstruction. It is classified as type V in the Mathes and Nahai classification and can be used as pedicled-islanded flap, free flap, and turnover flap. The flap is a popular choice for reconstruction of the defects over the occipital, parotid gland, cervical spine, and anterior neck. The superior fibers are designed mainly for head and neck reconstruction, but the arc of rotation is limited; however, it is possible to use the middle and inferior fibers of the trapezius for myocutaneous flaps.12,13

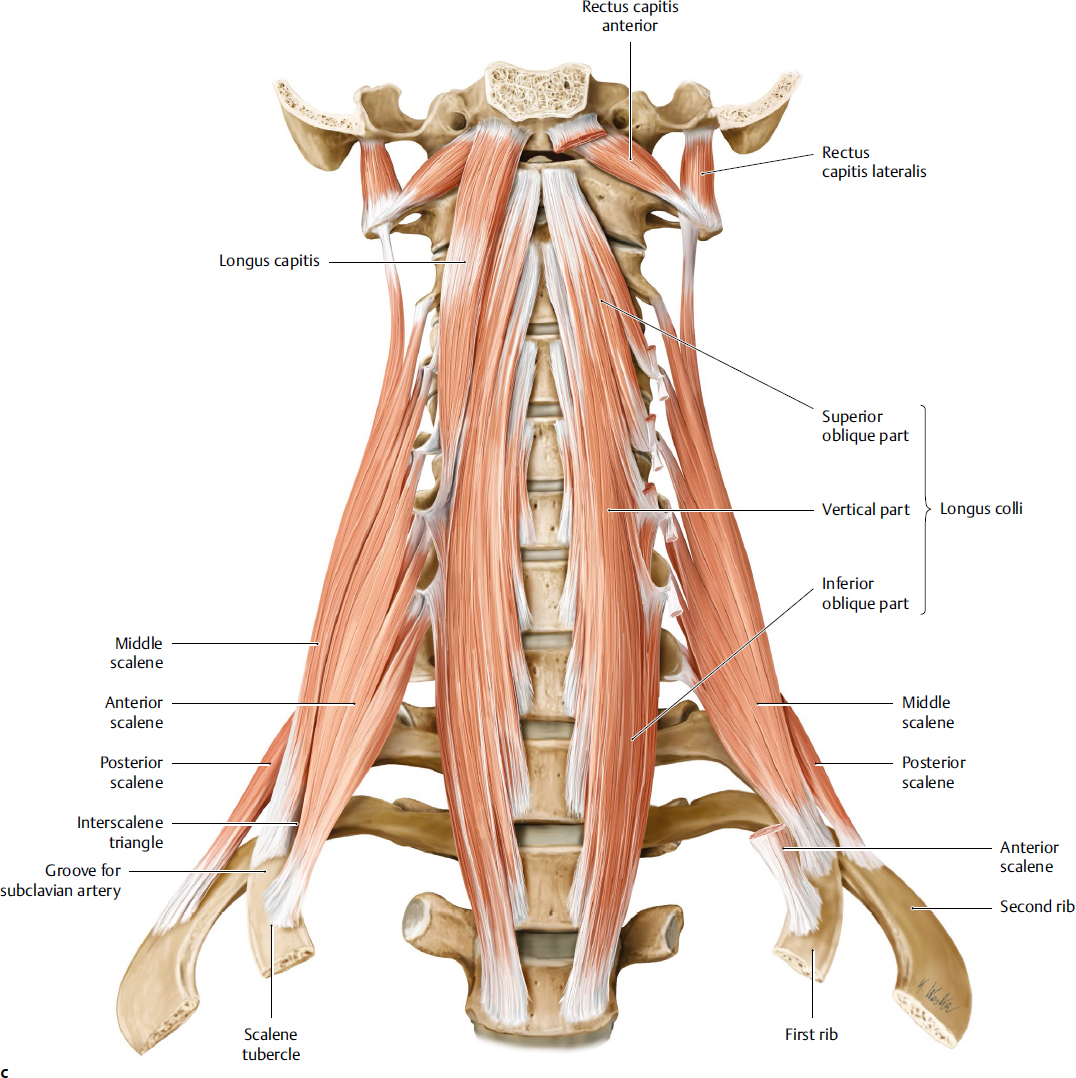

Paravertebral Muscles

The paravertebral muscles are located in front of the bodies of the cervical vertebrae, deep to the prevertebral fascia (Fig. 21.7c). The muscles are longus colli, longus capitis, rectus capitis anterior and lateralis, scalene muscles, and the levator scapulae.

• Blood supply: Vertebral arteries, ascending pharyngeal, and inferior thyroid arteries

• Nerve supply: Cervical spinal nerves

• Action: Scalene muscles are flexors and rotators of the vertebral column. The scalenus anterior and medius elevate the first rib and scalenus posterior elevates the second rib.

Postvertebral Muscles

The post vertebral muscles lie deep to the trapezius, behind the vertebral column, and are arranged in three layers: superficial layer (splenius cervicis and capitis muscles); middle layer (the erector spinae muscles); and deep layer (transversospinalis muscles). When acting on both sides of the splenius capitis, they cause extension of the head. The splenius cervicis is involved in the extension of the cervical spine. When acting on one side, they cause tilting of the head with slight rotation to one side.

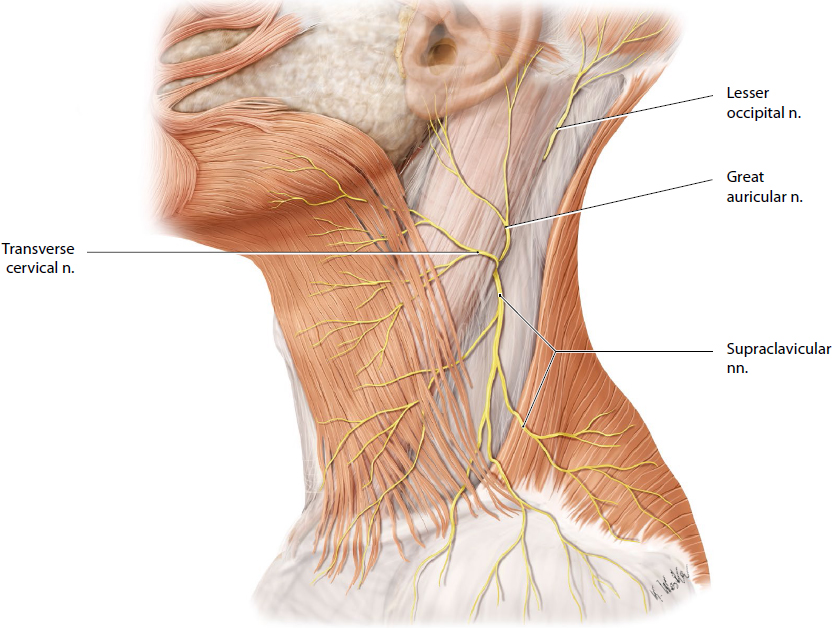

Peripheral Nerves of the Neck

The surface landmark of the great auricular nerve is referred to as the nerve point, located 6.5 cm inferior to the external auditory meatus. The nerve takes an oblique path toward the earlobe following the course of the external jugular vein. The vein lies about 0.5 cm medial to the nerve. Because the nerve is covered only by the SMAS superiorly, this layer should be identified to protect the nerve during dissection. Damage to the nerve leads to numbness of the lower two-thirds of the ear, preauricular skin, and postauricular skin and may result in neuroma formation.

Cervical Plexus

The cervical plexus is formed from the ventral rami of the first cervical nerves (C1–C4) and also receives anastomoses from the accessory nerve, hypoglossal nerve, and sympathetic trunk. Its cutaneous branches emerge from the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid approximately midpoint along the muscle; the motor divisions remain posterior to the sternocleidomastoid. The cutaneous branches of the cervical plexus include the lesser occipital nerve, greater auricular nerve, and the supraclavicular nerves (Fig 21.8). The motor branches are the ansa cervicalis and the segmental branches to the anterior and middle scalene nerves (Fig 21.9). The phrenic nerve arises from the cervical plexus and has both the sensory and motor components.

The dorsal rami of the first, sixth, seventh, and eighth cervical nerves have no cutaneous branches. The ansa cervicalis is part of cervical plexus, which mainly innervates the infrahyoid muscles. The brachial plexus is derived from the ventral rami of the cervical spinal nerves and lies deep in the posterior triangle of the neck. The cervical sympathetic trunk lies behind the carotid sheath on the prevertebral fascia. The main cutaneous branches of the cervical plexus are the lesser occipital, the great auricular, the transverse cervical, and the supraclavicular nerves. The lesser occipital nerve arises from the ventral ramus of the second and third cervical nerves and supplies the lateral part of the scalp. The greater occipital nerve is a branch of dorsal ramus of the second cervical nerve. This nerve is found in the suboccipital triangle; it pierces the trapezius and supplies the posterior scalp. The transverse cervical nerve arises from the second and third cervical nerves and passes across the sternocleidomastoid muscle to supply the skin on the anterior neck. The supraclavicular nerve receives fibers from the third and fourth cervical nerves. The nerve runs downward toward the clavicle and divides into three branches. These are the medial, intermediate, and lateral supraclavicular nerves, and they supply the skin over the lower neck and upper thorax.

The great auricular nerve arises from the second and third nerves of the cervical plexus and travels from a deep to superficial plane. The nerve reaches the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle at the junction of the superior and middle thirds of the muscle.14

Surgical Annotation

The phrenic nerves arise from C3, C4, and C5 and descend over the anterior scalene muscle deep to the prevertebral fascia.

The ventral and dorsal rami of the second and third cervical nerves innervate the anterior and posterior skin of the neck, respectively.

Cranial Nerves in the Neck

The cranial nerves in the neck are anatomically related to the carotid sheath. The vagus nerve runs within the carotid sheath, and the glossopharyngeal, accessory, and hypoglossal nerves are closely related to these structures.

The glossopharyngeal nerve exits the skull through the jugular foramen. The superior and inferior ganglia are found within the foramen. The nerve is found anterior to the vagus and accessory nerves and runs between the internal jugular vein and carotid artery. It winds around the stylopharyngeus muscle and passes between the superior and middle constrictors. The main branches include the tympanic, lesser petrosal, carotid, pharyngeal, tonsillar, lingual, and a branch to the stylopharyngeus muscle.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree