Morphea: Introduction

|

Morphea is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by sclerosis of the skin. The term “localized scleroderma” is also used in an attempt to highlight the systemic features of morphea. This causes confusion with systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) often resulting in unnecessary evaluation and anxiety. It is the opinion of the authors this term should be avoided. Morphea itself has a spectrum of manifestations ranging from skin only to multiple organ involvement. Of note, organ involvement in morphea is distinctly different from systemic sclerosis (Box 64-1).

Most Likely

Consider

Always Rule Out

|

Epidemiology

Morphea has an estimated incidence of 2.7 per 100,000 with a female:male ratio of 2 to 3:1.1 Morphea is more common in Caucasians.2–5 The relative frequency of the different subtypes varies between studies. This is likely due to use of different classification systems. Twenty to thirty percent of morphea begins in childhood, but it can occur at any age.2–5 Linear morphea is the most common pediatric subtype (although all subtypes occur at any age).1,2,6 Twenty-five to eighty-seven percent of pediatric cases are linear morphea, with limb or trunk involvement in approximately 70%–80% and en coup de sabre (ECDS) or progressive facial hemiatrophy (PHA; formerly described as Parry–Rhomberg) in 22%–30%.1,2,4,5,7,8 In adults, circumscribed and generalized subtypes predominate. Deep morphea/morphea profunda is uncommon in both adults and children with a frequency of 2%–4%.1,2,4,7,8

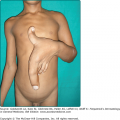

Periods of disease activity vary from 3 to 6 years, but reactivation after periods of remission occurs in 20%.2,8 (eFig. 64-0.1). Others have a chronic course persisting for decades. The prognostic markers for recurrent or chronic disease have yet to be determined.

eFigure 64-0.1

Chronicity and sequelae of morphea. Initial lesions began on the right leg at age 5 year of age, with new lesions on the abdomen at 16 years and on the right shoulder at 19 years of age. Note muscle atrophy, limb length discrepancy and pes planus foot deformity. (Reproduced with permission from Jacobe H: Morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults. In: UpToDate, edited by DS Basow. Waltham, MA, UpToDate, 2011. Copyright © 2011 UpToDate, Inc. For more information visit www.uptodate.com.)

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The etiology and pathogenesis of morphea is poorly understood. Most pathologic events ascribed to morphea are extrapolated from studies in systemic sclerosis (assuming the two disorders arise from the same etiology). Morphea probably arises from a genetic background that increases disease susceptibility, combined with other causative factors (infectious, environmental exposures) that modulate disease expression.

Like many autoimmune connective tissue diseases, morphea is likely a complex genetic disease. Familial clustering is rarely seen,5,9,10 and morphea is also associated with higher than expected rates of familial autoimmune disorders.5,11,12

Although there are no definitive associations, development of morphea lesions has been linked to local tissue trauma including radiation (eFig. 64-0.2), surgery, insect bites, and intramuscular injections.13 Although controversial, infectious agents have also been linked to lesion development.

eFigure 64-0.2

Morphea after breast reconstruction and irradiation. Biopsy to confirm that this lesion does not represent metastatic carcinoma of the breast is indicated. (Reproduced with permission from Jacobe H: Morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults. In: UpToDate, edited by DS Basow. Waltham, MA, UpToDate, 2011. Copyright © 2011 UpToDate, Inc. For more information visit www.uptodate.com.)

Increasing amounts of evidence support autoimmune-mediated inflammation early in the course of morphea.14 Early morphea lesions are characterized by the influx of large amounts of mononuclear lymphocytes (usually activated T lymphocytes), plasma cells, and eosinophils.15 This is likely the result of autoimmunity, as there is widespread autoimmune reactivity in morphea patients (elevated ANAs, cytokines, and adhesion molecules).5,12,16 Morphea patients also have concomitant autoimmune disease at higher expected frequency than a healthy population.5,11

Vessel damage and upregulation of adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, VCAM 1, and E-selectin) occur related to the inflammatory cell infiltrate which facilitates local monocyte recruitment.17 These adhesion molecules are upregulated by cytokines classically associated with a Th2 immune response (Il-4, Il-1, and TNFs). Cytokines found in the sera and skin of morphea patients in increased concentration include IL-4, IL-6, and IL-8.18 These cytokines (especially IL-4) upregulate TGF-β, initiating a cascade of events resulting in increased production of collagen and other extracellular matrix components via induction of connective tissue growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, and matrix metalloproteinases. These cytokines and growth factors inhibit interferon-γ (a suppressor of collagen synthesis and Th1-related cytokine). Chimerism or nonself cells may play a role in the pathogenesis of morphea by initiating a local inflammatory reaction.19

Clinical Findings

Morphea is currently divided into five subtypes (Table 64-1).20 Superficial or deep disease (involving subcutis, fascia, or below) may occur with any subtype. Morphea lesions may also occur with overlying lichen sclerosus change (Fig. 64-1).

Morphea Subtype | Modifiers | Clinical |

|---|---|---|

Circumscribed | Superficial | Single or multiple oval/round lesions limited to epidermis and dermis |

Deep | Single or multiple oval/round lesions involving subcutaneous tissue, fascia, or muscle. | |

Linear | Trunk/Limbs | Linear lesions involving possible primary site of involvement in subcutaneous tissue without involvement of skin, dermis, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, or bone |

Head | En coup de sabre, progressive facial hemiatrophy, linear lesions of the face (may involve underlying bone) | |

Generalized | ||

1. Coalescent plaque | More than or equal to four plaques in at least two of seven anatomic sites (head–neck, right/left upper extremity, right/left lower extremity, anterior/posterior trunk); isomorphic pattern: coalescent plaques inframammary fold, waistline, lower abdomen, proximal thighs; symmetric pattern: symmetric plaques circumferential around breasts, umbilicus, arms, and legs | |

2. Pansclerotic | Circumferential involvement of majority of body surface area (sparing fingertips and toes), affecting skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle or bone; no internal organ involvement | |

3. Mixed | Combination of any above subtype: e.g., linear-circumscribed | |

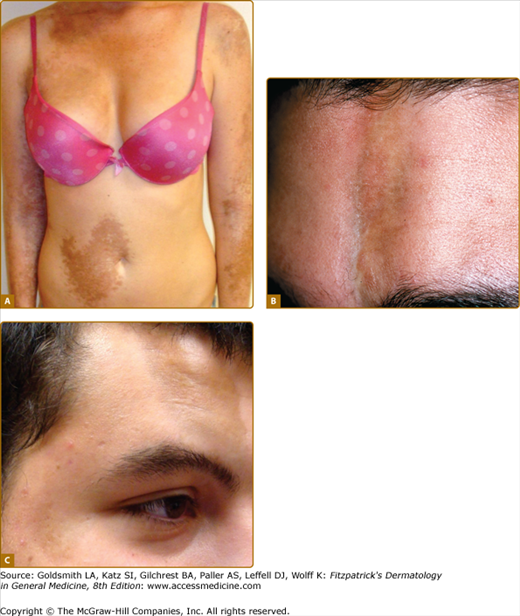

(Fig. 64-2).

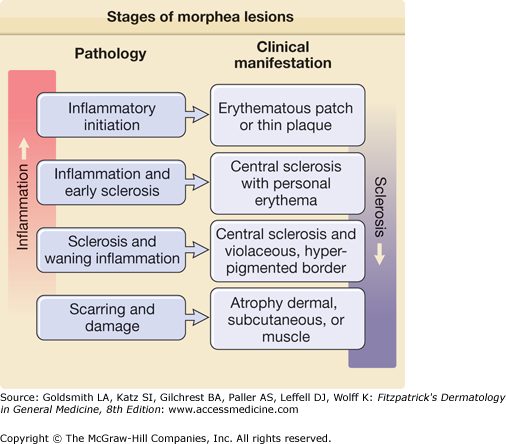

Morphea begins as erythematous plaques or patches, sometimes with a reticulated appearance. Later hypopigmented sclerotic plaques develop at the center of the lesion, surrounded by an erythematous or violaceous border (inflammatory stage) (Fig. 64-2A). Pain and/or itching can precede the initial skin findings. Sclerosis develops centrally, which turns into a shiny white color, as lesions expand with surrounding hyperpigmentation (sclerotic stage). There is loss of hair follicles, producing alopecia. Over months to years, the sclerotic plaque softens and becomes atrophic with hypo- or hyperpigmentation (atrophic stage) (Fig. 64-2B). The atrophic stage is associated with cigarette paper wrinkling (papillary dermis), cliff drop (dermal), or deep indentions (subcutis or deeper).

Figure 64-2

Stages of morphea lesions. A. Typical active morphea plaque in inflammatory stage, with violaceous border. B. Severe atrophy in patient with linear morphea (atrophic stage). (Reproduced with permission from Jacobe H: Morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults. In: UpToDate, edited by DS Basow. Waltham, MA, UpToDate, 2011. Copyright © 2011 UpToDate, Inc. For more information visit www.uptodate.com.)

Circumscribed morphea represents oval to round lesions undergoing the stages of activity described in the previous section that are not diffuse enough to meet criteria for generalized disease (Table 64-1). Patients with circumscribed morphea should be closely followed, as both linear and generalized morphea may begin with circumscribed lesions.

Atrophroderma of Pasini and Pierini are thought to be the residua of plaque-type morphea. The borders of the atrophoderma lesions have a “cliff-drop” appearance resembling “burnt-out” morphea lesions.

Generalized morphea is characterized by more than or equal to four lesions on at least two of seven different anatomic sites. There are likely three variants of generalized morphea: (1) isomorphic, (2) symmetric, and (3) pansclerotic (Table 64-1; Figs. 64-3 and 64-4).21,22 In direct contrast to systemic scleroderma, generalized morphea does not present with acrosclerosis or sclerodactyly. Instead, lesions frequently begin on the trunk and spread acrally, sparing the fingers and toes (Fig. 64-4).

Figure 64-3

Generalized morphea. A. Isomorphic plaques involving bra and waistband areas. B. Symmetric plaques on a patient with generalized morphea. (Reproduced with permission from Jacobe H: Morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults. In: UpToDate, edited by DS Basow. Waltham, MA, UpToDate, 2011. Copyright © 2011 UpToDate, Inc. For more information visit www.uptodate.com.)

Figure 64-4

Pansclerotic morphea: sclerosis encompassing majority of body surface area (A), characteristically sparing the fingertips (B). (Reproduced with permission from: Jacobe H: Morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults. In: UpToDate, edited by DS Basow. Waltham, MA, UpToDate, 2011. Copyright © 2011 UpToDate, Inc. For more information visit www.uptodate.com.)

Linear morphea usually affects the extremities and face, but it can occur on the trunk (where it is often misclassified as circumscribed) (Table 64-1, Fig. 64-5A). The presence of multiple linear lesions is not uncommon. A recent study suggests that linear morphea may follow Blaschko’s lines.23 Linear morphea may involve the dermis, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, or even underlying bone, causing significant deformities. Bone marrow inflammation has also been reported.24,25 ECDS “cut of the sword” may present as an atrophic band linear plaque on the forehead (Fig. 64-5B), extending to the scalp (where cicatricial alopecia occurs), brow, nose, and lip. Other linear lesions on the head and neck present on the temple or chin, and are generally hyperpigmented atrophic plaques (Fig. 64-5C). PHF is characterized by a slowly progressive, unilateral atrophy of skin, soft tissues, muscles, and/or bony structures. The atrophy may be accompanied by classic linear morphea lesions on the face or elsewhere.

Figure 64-5

A. Multiple linear lesions involving trunk and extremities. B. En coup de sabre. C. Multiple hyperpigmented linear morphea lesions on the face. (Reproduced with permission from: Jacobe H: Morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults. In: UpToDate, edited by DS Basow. Waltham, MA, UpToDate, 2011. Copyright © 2011 UpToDate, Inc. For more information visit www.uptodate.com.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree