Modified Radical Mastectomy and Total (Simple) Mastectomy

Kirby I. Bland

In 1867, Charles H. Moore (1) stated the following: “Sometimes the tumor only is removed; sometimes the segment of the breast (where the tumor lies) is taken away…; sometimes… the entire mamma. Mammary cancer requires the careful extirpation of the entire organ.”

Introduction

Historical Aspects and Development of the Modified Radical Mastectomy

Modified radical mastectomy has evolved in American surgery as one of the most common surgical procedures completed by general surgeons and surgical oncologists. This procedure followed by some 60 years the development by William Stewart Halsted (2) and Willie Meyer (3) both of whom independently reported, in 1894, the successful therapy of advanced breast carcinoma with radical mastectomy. The synthesis of mastectomy techniques by Halsted and Meyer’s predecessors in surgery and pathology, therefore, allowed them to achieve unprecedented success to obtain this objective without the availability of irradiation or chemotherapy. These techniques for the Halsted radical mastectomy provided evolution of modified radical techniques that allowed varying degrees of breast extirpation and lymphatic dissection (Table 19.1). The modified radical mastectomy has clearly defined complete breast removal, inclusion of the tumor and its overlying skin, and regional axillary lymphatics, with preservation of the pectoralis major muscle. Unequivocally, preservation of this muscle has provided better cosmesis of the chest wall and has variable outcomes to enhance motor function of the shoulder when pectoralis major preservation and neurovascular innervation is ensured (4).

Table 19.1 Historical Development of Modified Radical Mastectomy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Of historical interest are the following:

The modified radical mastectomy represents the most common operation done in general surgery as an ablative technique for cancer. This procedure entails

en bloc resection of the breast, which is inclusive of the nipple–areolar complex, axillary lymphatics, and the overlying skin surrounding the tumor and

primary closure, which may include reconstruction methods.

The variations of the technique were originally described by Auchincloss (15), Hanley (16), and Madden (17) and preserve the pectoralis major and minor muscles protecting their neurovascular innervation, with incomplete clearance of level III nodes that are medial and caudal to the axillary vein. The surgeon should ensure preservation of the medial pectoral neurovascular bundle, as this neurovascular complex commonly penetrates the pectoralis minor muscle with innervation of the pectoralis major.

The Patey technique involves removal of the pectoralis minor muscle to allow clearance of level III (medial–caudal) nodal group to ensure complete axillary node dissection (18,19). While the modified radical technique attempts to spare the medial and lateral pectoral nerves, the more extended nodal removal (to level III apical group) synchronous with resection of the pectoralis minor muscle makes pectoral nerve preservation more difficult to accomplish. Proportional loss of nerve innervation to the pectoralis major will induce atrophy of this muscle group.

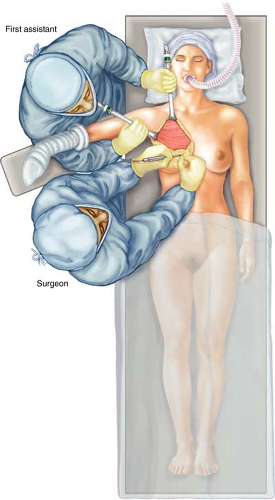

Anesthesia and positioning (Fig. 19.1): The modified radical technique requires supine positioning prior to induction with general endotracheal anesthesia. Preferably,

the patient’s hip and shoulder should be aligned with the edge of the operating table to allow simple access to the operating field without undue traction on muscle groups and to avoid stretch-injury to the brachial plexus. Further protection of the brachial plexus from shoulder retraction should be achieved by placing the ipsilateral arm onto a padded arm board with slight elevation of the ipsilateral hemithorax to allow complete rotation and movement of the relaxed shoulder in the operating field.

Preparation of the skin: Prior to draping, the ipsilateral breast, neck, hemithorax, shoulder, axilla, and arm are prepped with standard povidone–iodine solution. In the case of iodine allergies, alternative sterile prep solutions are recommended. The prep should extend across the midline, inclusive of the complete circumferential prep of the ipsilateral shoulder, arm, and hand. We prefer isolation of the ipsilateral forearm and hand with Stockinette® dressing secured by Kling® or Kerlex® cotton rolls. Sterile drapes are placed to provide a wide operative field and are secured to the skin,

preferably with staples. The first assistant is positioned craniad to the shoulder of the ipsilateral breast to provide retraction and arm mobilization without undue stretch traction on the brachial plexus. Following positioning and preparation, adequate mobility of the ipsilateral shoulder and arm should be confirmed prior to surgical incision (Fig. 19.2).

Skin Incision and Topographical Limits of Dissection

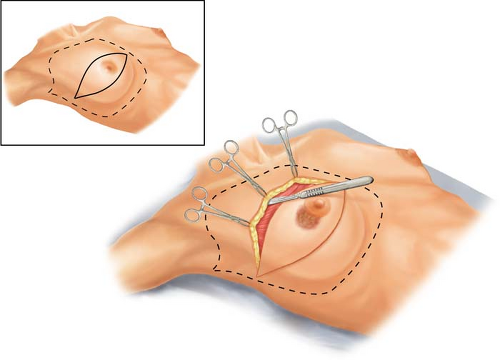

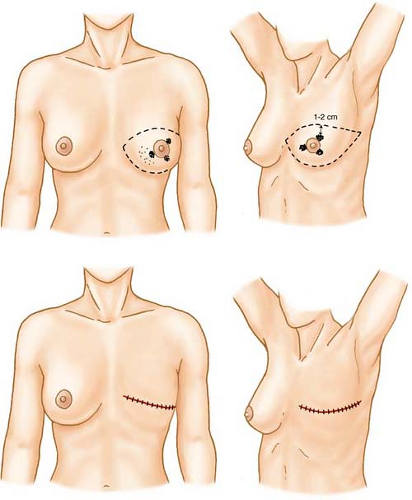

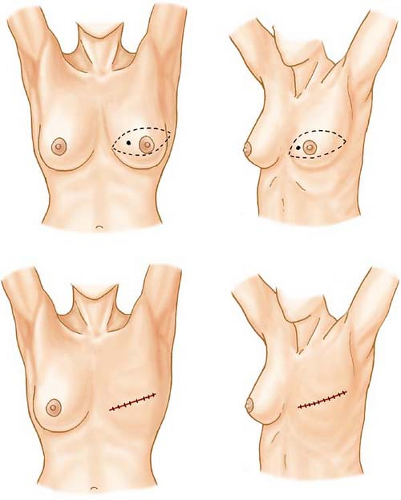

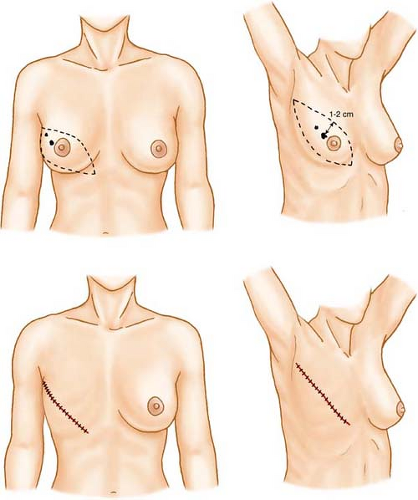

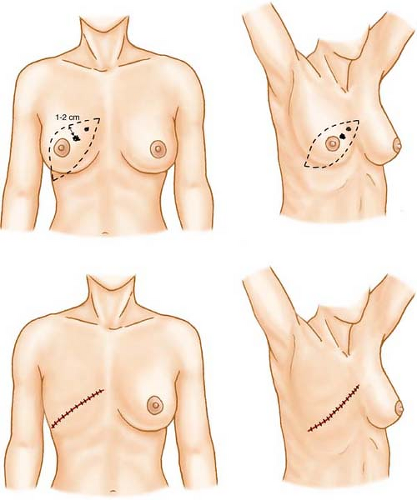

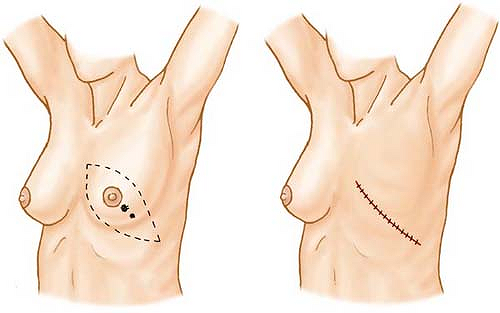

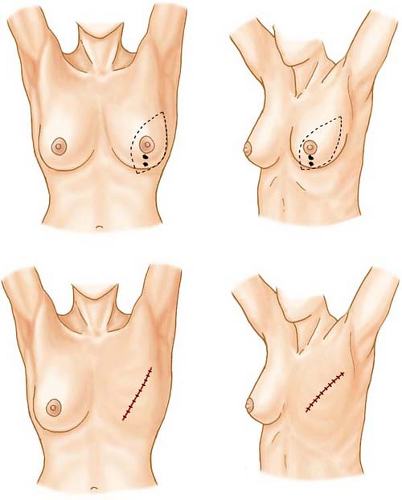

Figures 19.3 through 19.9 confirm the various locations of breast primaries in which adequate therapy with and without irradiation or chemotherapy necessitates total mastectomy. These incisions are planned when conventional techniques are to be utilized without planned immediate reconstruction. While previously recommended wide (radical) skin margins of greater than 5 cm were considered essential for local–regional control, current data would suggest that skin margins of 1 to 2 cm from the gross margin of the index tumor are necessary and adequate to ensure final pathology-free margins. Margins in excess of 2 cm are technically feasible for the majority of total mastectomies in which reconstruction (early or delayed) will not be completed. Clearly, preoperative planning and consideration of the types of incisions are essential for the general surgical oncologist. Preoperative consideration should be given to the skin-sparing technique when the patient desires reconstruction. The most commonly applied elliptical excision for central and subareolar breast primaries is the classical Stewart incision

(Fig. 19.3) or the modification of the Stewart incision of the inner lower quadrant of the breast. For lesions in the upper outer quadrant, the classical Orr incision is preferred.

(Fig. 19.3) or the modification of the Stewart incision of the inner lower quadrant of the breast. For lesions in the upper outer quadrant, the classical Orr incision is preferred.

Limits of the modified radical procedure are as follows:

delineated laterally by the anterior margin of the latissimus dorsi muscle,

delineated medially by the sterno–caudal junction border,

delineated superiorly by the subclavius muscle, and

delineated inferiorly by the caudal extension of the breast to approximately 2 to 3 cm below the inframammary fold.

Skin incisions are planned perpendicularly to the subcutaneous plane; retraction hooks or towel clips are placed on skin margins to provide adequate perpendicular retraction to the plane of dissection. Retraction should be achieved with constant tension on the periphery of the elevated skin margin at right angles to the chest wall. An essential technique is that of “countertraction” of the operating surgeon against the assistant’s retraction to maintain constant flap thickness and improve visualization within the operative field. Skin flap thickness will vary on the basis of patient body habitus, but it is ideally between

6 and 8 mm. The interface for flap elevation is developed deep to the cutaneous vasculature with avoidance of the parenchymal vasculature and should be maintained evenly to achieve constant thickness, which will abrogate devascularization of tissue planes.

6 and 8 mm. The interface for flap elevation is developed deep to the cutaneous vasculature with avoidance of the parenchymal vasculature and should be maintained evenly to achieve constant thickness, which will abrogate devascularization of tissue planes.

Topographical Anatomy

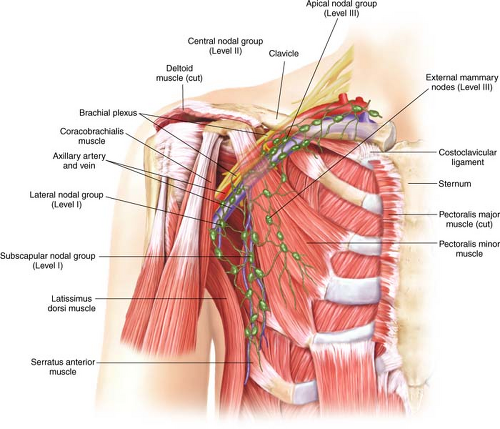

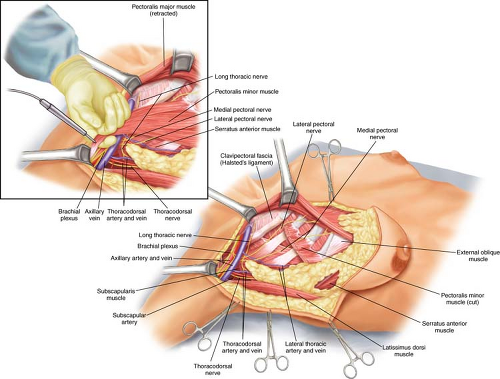

Figure 19.10 represents the topographical anatomy of levels I, II, and III of the axillary contents relative to the neurovascular bundle, pectoralis minor, latissimus dorsi, and

posterior axillary space relative to the chest wall. Level I nodes comprise three principal groups of axillary nodes: the external mammary group, the subscapular group, and the axillary vein (lateral group). Level II, the central nodal group, is centrally placed upon and immediately beneath the pectoralis minor muscle and overlies the exposed axillary vein. The subclavicular (apical) group is designated level III nodes and represents that group of nodes cephalomedial to the pectoralis minor.

posterior axillary space relative to the chest wall. Level I nodes comprise three principal groups of axillary nodes: the external mammary group, the subscapular group, and the axillary vein (lateral group). Level II, the central nodal group, is centrally placed upon and immediately beneath the pectoralis minor muscle and overlies the exposed axillary vein. The subclavicular (apical) group is designated level III nodes and represents that group of nodes cephalomedial to the pectoralis minor.

Figure 19.6 Variation of the Orr incision for lower inner and vertically placed (6 o’clock) lesions of the breast. The design of the skin incision is identical to that of Figure 20.4, with attention directed to margins of 1 to 2 cm. |

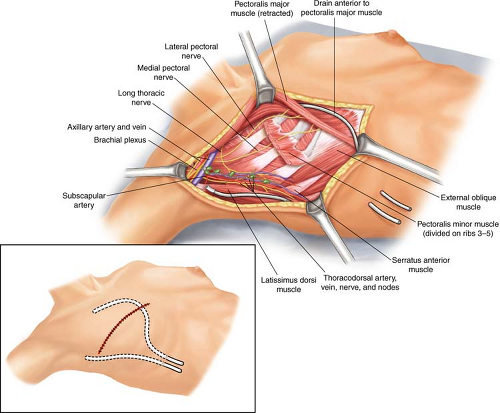

The conduct of the modified radical mastectomy, in contemporary terms, utilizes a dissection of level I and II nodes and spares the pectoralis major and minor muscles as

formerly described by Patey (Fig. 19.11). Removal of the breast is completed from cephalad to caudad with the inclusion of the pectoralis major fascia, as well as portional resection of the pectoralis major when tumor extension into the muscle is recognized clinically or radiographically. The pectoralis major fascia is dissected from the musculature in a plane parallel to the course of the muscle fibers. This technique avoids entry and exposure of muscle perforators and ensures minimal blood loss. The operator applies constant inferior traction on the breast and the fascia. Multiple perforated vessels will be encountered from

the lateral thoracic or anterior intercostals arteries that supply the pectoralis muscles. These perforators must be identified, clamped, divided, and ligated or clipped.

formerly described by Patey (Fig. 19.11). Removal of the breast is completed from cephalad to caudad with the inclusion of the pectoralis major fascia, as well as portional resection of the pectoralis major when tumor extension into the muscle is recognized clinically or radiographically. The pectoralis major fascia is dissected from the musculature in a plane parallel to the course of the muscle fibers. This technique avoids entry and exposure of muscle perforators and ensures minimal blood loss. The operator applies constant inferior traction on the breast and the fascia. Multiple perforated vessels will be encountered from

the lateral thoracic or anterior intercostals arteries that supply the pectoralis muscles. These perforators must be identified, clamped, divided, and ligated or clipped.

Resection of the pectoralis minor muscle is not necessary except for planned resection of clinically positive level III nodes. When such exposure is essential for planned resection of the pectoralis minor, the latter dissection begins with proper positioning such that the shoulder of the ipsilateral arm is abducted in the field. Figure 19.1 confirms the assistant holding the arm for relief of the brachial plexus. The borders of the pectoralis minor are digitally delineated and retracted to visualize the insertion of the pectoralis minor on the coracoid process where it can be divided with electrocautery (inset of Fig. 19.11). Care must be taken to identify and preserve the medial and lateral pectoral nerves as they penetrate the pectoralis minor in their course for neuronal innervation of the muscle groups. These nerves may be sacrificed if the pectoralis minor resection is planned. Following resection of the pectoralis minor muscle, superior visualization of level III nodes is ensured following resection of the insertion of this muscle on ribs 2 to 5. Protection of the full extent of the pectoralis vein as it courses beneath the pectoralis minor en route to entry between ribs 1 to 2 is essential to avoid venous

injury. Retraction of all nodal groups from the inferior and ventral surface of the axillary vein at the apical-most extent of the nodes ensures complete resection of level III. When level III dissection is necessary, this level should be tagged or clipped to indicate the highest resection level.

injury. Retraction of all nodal groups from the inferior and ventral surface of the axillary vein at the apical-most extent of the nodes ensures complete resection of level III. When level III dissection is necessary, this level should be tagged or clipped to indicate the highest resection level.

Contemporary therapeutic principles require planned resection of only levels I and II; thus resection of the pectoralis major and minor in most circumstances can be avoided, except with clinically positive or radiographically evident nodal disease at level III.

Dissection of Axillary Lymph Nodes

Dissection of axillary nodes (Fig. 19.12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree