Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Introduction

|

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an increasingly common neuroendocrine skin cancer that is associated with ultraviolet (UV)-light exposure, advanced age, immune suppression and a recently discovered polyomavirus. The reported incidence of MCC has more than tripled in the past 20 years1 to approximately 1,500 US cases/year2 and is expected to grow with the aging population. Although it is 40 times less common than malignant melanoma, it carries a markedly poorer prognosis, with disease-associated mortality at 5 years of 46%3 as compared with 9% for invasive melanoma.4 Management of MCC is challenging and optimal therapy is controversial, at least in part due to a lack of prospective or randomized data on which to base treatment decisions.

MCC is a relatively recently described entity, although the Merkel cell was identified more than 100 years ago. In 1875, human Merkel cells were first described by Friedrich S. Merkel (1845–1919). He named these cells Tastzellen (touch cells) assuming that they had a sensory touch function within the skin due to their association with nerves. In 2009, a series of studies using elegant mouse models resolved several long-standing debates by conclusively establishing that (1) Merkel cells are essential for light touch responses,5 (2) Merkel cells have an epidermal origin,5,6 and (3) Merkel cells do not divide, but are renewed by a reservoir of epidermal progenitor cells.6

In terms of what we now call Merkel cell carcinoma, in 1972, Toker described five cases of “trabecular cell carcinoma of the skin.” In 1978, Tang and Toker found that cells from these tumors contained dense core granules on electron microscopy that were typical of Merkel cells and other neuroendocrine cells. In 1980, the name Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) was first applied to this tumor because of the characteristic ultrastructural features it shares with normal Merkel cells. In 1992, it was found that antibodies to cytokeratin-20 stain normal skin Merkel cells as well as the vast majority of MCC tumors. This critical finding allows specific and relatively easy diagnosis of MCC to be made through immunohistochemistry. Since that time, electron microscopy is no longer used to make this diagnosis.

Epidemiology

Over the 20-year period between 1986 and 2006, the reported incidence of MCC quadrupled from 0.15 per 100,0001 to 0.6 per 100,000.7 There are likely two factors that contribute to this increase in reported incidence that is more rapid than that of any other type of skin cancer. One factor is an increase in the accurate diagnosis of this malignancy through the routine use of cytokeratin-20 immunohistochemistry and the improved recognition of this malignancy by dermatopathologists. In the past, MCCs were often mischaracterized as lymphoma, melanoma, or undifferentiated carcinoma in the era before immunohistochemistry. A second likely reason is an increase in the number of people over age 65 years with extensive sun exposure history and people living with prolonged immune suppression. Each of these factors is a known risk factor for MCC and several are discussed in Section “Etiology and Pathogenesis.”

As of 2008, there are approximately 1,500 MCC cases per year in the US.2 This cancer is far more common in whites than in blacks, consistent with a known role for UV radiation in MCC pathogenesis. Specifically, the rates in whites have been reported as 0.23 per 100,000 as compared to 0.01 per 100,000 for blacks.8 Although not specifically reported, rates in Hispanics and Asians are likely intermediate between those in blacks and whites. MCC tends to be more common in men than in women (2:1 in ratio).9 Furthermore, men also tend to have a worse prognosis than women, with reported 10-year disease-associated survival rates of 51% for men and 65% for women.7

Etiology and Pathogenesis

There are several known risk factors for MCC that will likely continue to lead to an increase in the incidence of this disease.

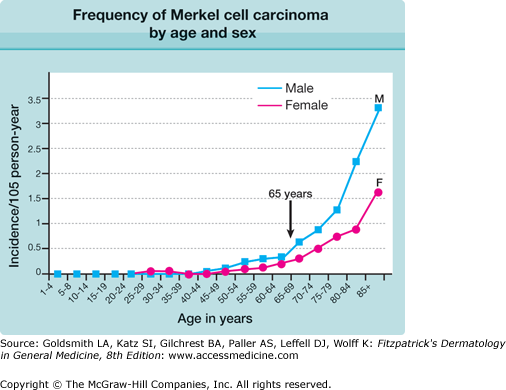

The median age for diagnosis of MCC is 70 years, and there is a five- to tenfold increase in incidence after age 70 as compared with age less than 60 years, as shown in Fig. 120-1. Indeed, only about 10% of MCC cases present in patients under age 50 and it is extremely rare in childhood.10

Figure 120-1

Frequency of Merkel cell carcinoma by age and sex. The most significant risk factor for Merkel cell carcinoma is age. M, male (▪); F, female (•). (Reprinted from Agelli M, Clegg LX: Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol 49:832, 2003, with permission.)

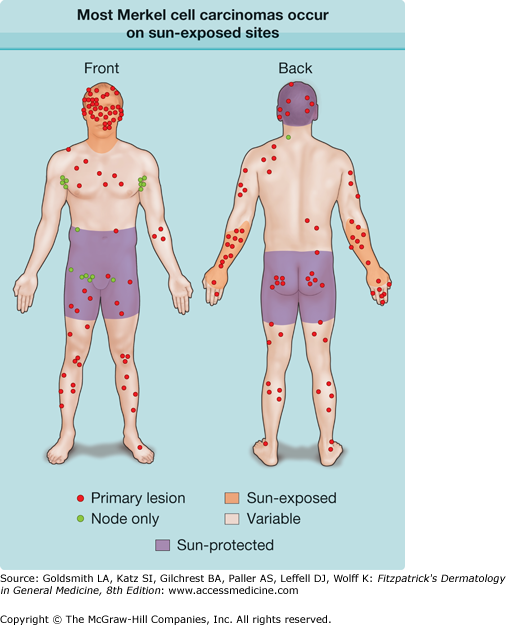

Sunlight, prolonged UV exposure, and photochemotherapy are all associated with an increased risk of MCC. As seen in Fig. 120-2, the vast majority (81%) of MCC tumors present on sun-exposed skin.10 However, it is clear that sun is not required for MCC to develop. MCC cases can occur on sun-protected skin, including buttocks and vulva as well as portions of the scalp that are covered by hair.

Figure 120-2

Most Merkel cell carcinomas (MCCs) occur on sun-exposed sites. This diagram shows the locations of tumor presentation for 195 MCC patients. For 168 patients, the site of the primary skin tumor is shown (red circles). The remaining 27 patients had no known primary and instead presented with nodal metastasis (green circles). The majority of patients (81%) presented with a primary tumor located on the heavily sun exposed face, neck, or dorsal forearm (brown shading). Five percent of patients presented with tumors in completely sun protected skin areas (purple shading), and 14% of patients presented with MCC in partially sun-protected skin (skin tone). (Adapted from Heath M et al: Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: The AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol 58:375-81, 2008.)

As compared to most cancers, MCC is strongly linked to immune suppression. Indeed, 7.8% of MCC patients are profoundly immune suppressed, a 16-fold overrepresentation compared with expected.10 Multiple forms of immune suppression are associated with an increase in MCC risk. These include HIV/AIDS,11 chronic lymphocytic leukemia,10 and the immune suppressive regimens associated with solid organ transplant.9 Additionally, there are 19 reported cases of complete spontaneous regression in the MCC literature, a far greater number than expected for its rarity, perhaps suggesting a sudden immune recognition and clearance of MCC.8,12

In 2008, a new polyomavirus, the Merkel cell polyomavirus (abbreviated MCV or MCPyV), was discovered by extensive sequencing of MCC tumor RNA. MCPyV was reported to be present in 80% of MCC tumors compared to only 7% of skin controls.13 Numerous groups across several continents (over 25 literature citations) have verified the association between MCPyV and MCC, and all groups observed that the virus is strongly associated with MCC. MCPyV is a small, circular, double-stranded DNA virus related to other known polyomaviruses (SV40, BK, JC, KI, WU). MCPyV is unique among the human polyomaviruses as it is the only one proven to integrate into a human cancer. Monoclonal integration of MCPyV into MCC tumors suggests that the virus is present prior to or very early in tumorigenesis.

A large fraction of the population has been infected with MCPyV. By the age of 5, prevalence of antibodies is about 35%, but increases to 50% by the age of 15.14 Interestingly, among MCC patients, the prevalence is significantly higher (88%) than age and sex-matched controls (53%).15 Importantly, despite how common exposure is to this virus in the general population, the incidence of MCC is very low. Therefore, viral infection alone is clearly insufficient for the development of this cancer.

Clinical Presentation of Merkel Cell Carcinoma

A systematic analysis of 195 MCC patients characterized clinical features that may serve as clues in the diagnosis of MCC.10 The most significant features can be summarized in an acronym: “AEIOU” (Table 120-1). This study found that 89% of 62 MCC cases exhibited at least three of the five features listed below. If a lesion exhibits at least three of these features, suspicion of MCC should increase and biopsy be considered. In particular, a lesion that is red or purple, rapidly growing, but nontender should be of concern. Strikingly, the clinician listed as clinical impression a benign diagnosis in over one half of cases. In particular, a cyst or acneiform lesion was the single most common of these (Box 120-1 and Figs. 120-3A and 120-3B) and nonmelanoma skin cancer was also relatively frequent as a presumptive diagnosis (Fig. 120-3C).

Asymptomatic (non-tender, firm, red, purple, or skin-colored papule or nodule; ulceration is rare; see Figs. 120-3A and 120-3B) |

Expanding rapidly (significant growth noted within 1–3 months of diagnosis, but most lesions are <2 cm at time of diagnosis) |

Immune suppression (e.g., HIV/AIDS, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, solid organ transplant) |

Older than 50 years |

| Ultraviolet-exposed site on a person with fair skin (most likely presentation, but can also occur in sun-protected areas; Fig. 120-2) |

Most Likely

|

Consider

|

Figure 120-3

Clinical appearance of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). A. MCC frequently has a “cyst-like” appearance. This is reflected in the differential diagnoses given by clinicians at the time of the biopsy, with cyst/acneiform lesion being the most common clinical impression. B. MCC on the knee of a 70-year-old woman with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. For 6 months this lesion was thought to be a “cyst”; consequently, diagnosis and treatment were delayed. Pen marks indicate palpable satellite metastases that developed several months after the primary lesion, presumably tracking via lymphatics. C. MCC on the ear of an 87-year-old woman. The lesion grew rapidly and was nontender. After approximately 3 months, it was biopsied by a clinician who listed squamous cell carcinoma as the presumptive diagnosis.

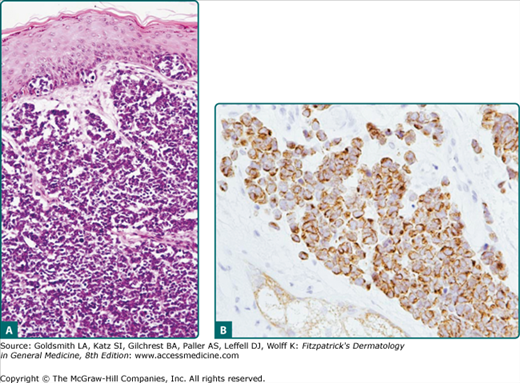

Pathology

As shown in Fig. 120-4A, the classic histologic features of MCC include sheets of small basophilic cells with scant cytoplasm, fine chromatin, and no nucleoli. There are numerous mitotic figures and occasional individual necrotic cells. Lymphovascular invasion is a very common feature and often can be found when it is specifically searched for even in a “negative” margin. This helps to explain the high local recurrence rate in MCC for narrow or even relatively wide margin excision when adjuvant radiation therapy is not given.

Figure 120-4

Merkel cell carcinoma pathology. A. Hematoxylin and eosin. There is diffuse dermal as well as intraepidermal involvement with Merkel cell carcinoma. This case was seen in consultation, with an initial diagnosis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. B. Cytokeratin-20. Showing the pathognomonic “perinuclear pattern” of cytokeratins (CAM5.2). [Reprinted from Nghiem P, Mckee P, Haynes H: Merkel cell (cutaneous neuroendocrine) carcinoma. In: Skin Cancer, Atlas of Clinical Oncology, edited by A Sober, F Haluska, American Cancer Society, 2001, with permission.]