Mastocytosis: Introduction

|

|

Epidemiology

Mastocytosis represents a group of disorders characterized by an abnormal accumulation of mast cells in one or more organs. While the true incidence of this disease is unknown, most cases are in children, with 60%–80% presenting within the first year of life. Congenital mastocytosis is less common, representing approximately 18%–31% of childhood cases.1,2 Adult-onset mastocytosis also occurs and is being more commonly recognized with newly established World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for this disease3 (Tables 149-1 and 149-2). This disorder has no gender preference, and it has been reported in all races.4 While most patients with mastocytosis have no family history, there are reports of familial cases, including monozygotic twins, some of which were discordant for this disease.4–6

Variant Term | Abbreviation | Subvariants | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

Cutaneous mastocytosis | CM | Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans (TMEP) | Urticaria pigmentosa Diffuse CM Mastocytoma of skin |

Indolent systemic mastocytosis | ISM | Smoldering SM Isolated bone marrow mastocytosis | SM-acute myelogenous leukemia SM-myelodysplastic syndrome SM-myeloproliferative disease SM-chronic myelomonocytic leukemia SM-non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

Systemic mastocytosis with an associated clonal hematologic nonmast cell lineage disease | SM-AHNMD | ||

Aggressive systemic mastocytosis Mast cell leukemia Mast cell sarcoma | ASM MCL MCS | ||

Extra-cutaneous mastocytoma | ECM |

Major Multifocal dense infiltrates of mast cells in bone marrow and/or other extracutaneous organs |

Minor More than 25% of the mast cells in bone marrow aspirate smears or tissue biopsy sections are spindle shaped or display atypical morphology. Detection of a codon 816 c-kit point mutation in blood, bone marrow, or lesional tissue. Mast cells in bone marrow, blood, or other lesional tissue expressing CD25 or CD2. Baseline total tryptase level greater than 20 ng/mL. |

Pathogenesis

Mast cells arise from the bone marrow as agranular, undifferentiated, CD34+, KIT+ (CD117) pluripotent progenitor cells. After migrating into tissues, immature mast cells assume their typical granular morphology.7 KIT is a type III tyrosine kinase receptor product of the proto-oncogene c-kit located on chromosome 4q12. This enzyme is expressed on mast cells, as well as melanocytes, primitive hematopoietic stem cells, primordial germ cells, and interstitial cells of Cajal. Cross-linking KIT by its ligand, stem cell factor (SCF), is essential for precursor cells to differentiate into mast cells. The gene for SCF is located on chromosome 12, and encodes a protein that localizes to the cell membrane.7,8 Membrane-bound and a soluble forms of SCF exist, both of which are capable of inducing KIT activation. Soluble KIT is thought to arise from chymase-induced cleavage of the membrane bound form.9 SCF is produced by bone marrow stromal cells, fibroblasts, keratinocytes, endothelial cells, as well as reproductive Sertoli and granulosa cells. Mature mast cells require SCF for survival.8,9 Other cytokines that appear important in regulating mast cell growth and differentiation include interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-4, IL-6, and IL-9 and IFN-γ. IL-3 shares a number of signal transduction pathways with SCF, but has minimal direct effects on human mast cell proliferation except in early cultures. IL-4 enhances mast cell function when added to mature cultures. IL-6 has been shown to increase mast cell mediator concentration,10 and IL-9 appears to increase the number of mast cells in culture.11 In developing mast cells, IFN-γ inhibits mast cell proliferation and influences mast cell phenotype and function.10

Mutations in c-kit appear to play a central role in some forms of mastocytosis. Somatic mutations in codon 816 of c-kit, leading to amino acid substitutions (D816V, D816Y, D816F, and D816H), cause constitutive activation of KIT and continued mast cell growth and development.12 Mutations in this codon are most common in adults with mastocytosis.3 An activating mutation in codon 560 (V560G) also has been characterized in some adult patients with mastocytosis, but appears to be much less common.6,13 Activating mutations in c-kit have been reported in children with mastocytosis as well. Among 50 children with this disorder, 42% had detectable mutations of codon 816 (exon 17), while another 42% had demonstrable activating mutations in the extracellular and transmembrane regions of KIT (exons 8–11). The remaining eight children reported in the study had no detectable c-kit mutations.14 There was no clear correlation between the extent of disease and the presence or absence of c-kit mutations among these patients. In another report of 22 children and adults with mastocytosis, 11 adult patients and 4 children had 816 activating mutations. Four other pediatric patients with typical lesions of urticaria pigmentosa (UP) lacked changes in this codon, and in three other children, an inactivating c-kit mutation (codon E839K) was detected.12

A transgenic mouse model of mastocytosis also has been reported using the human activating D816V c-kit mutation.15 The clinical expression of this disorder ranged from indolent mast cell hyperplasia to invasive mast cell tumors, despite the fact that genetically identical animals expressed the same D816V mutation. It appears from these clinical and investigative observations that c-kit activating mutations of codon 816 play an important role in the development of mastocytosis. However, the finding of a varied clinical expression of mastocytosis in an animal model along with that fact that some children with mastocytosis have no c-kit mutations or have inactivating c-kit mutations strongly suggests that other, yet to be defined, factors influence the full clinical expression of this disease.

Clinical Findings

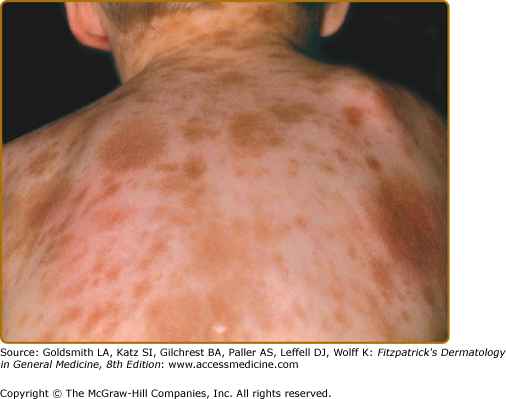

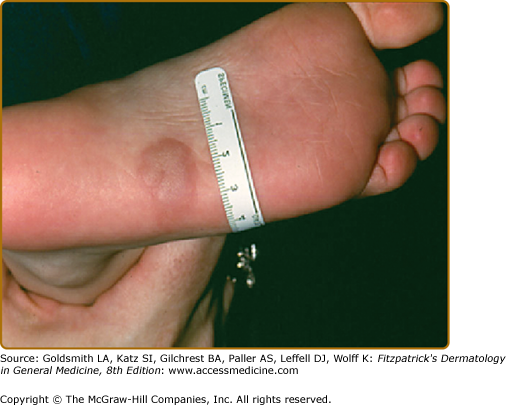

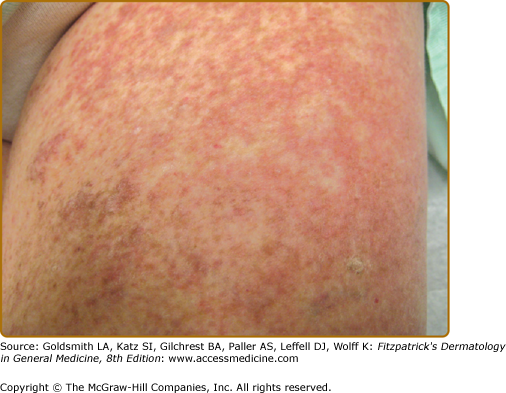

Mastocytosis represents a disease spectrum characterized by a diverse phenotypic expression, along with pathologic and genetic findings that affect prognosis. Table 149-1 represents the WHO classification of mastocytosis.3 Cutaneous mastocytosis (CM) and indolent SM (ISM) represent the majority of patients with this disease. Most children have CM, which is manifested as UP (Fig. 149-1) or less commonly as mastocytomas (Fig. 149-2) or diffuse CM (Fig. 149-3). SM occurs mostly in adults, and ISM is the most common form. Criteria for SM are listed in Table 149-2. Systemic mastocytosis with an associated clonal hematologic, nonmast cell lineage disease (SM-AHNMD) appears unique to adults. In this group, examination of the bone marrow and peripheral blood reveals a hematologic abnormality. Hematologic disorders associated with SM-AHNMD include myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic disorders such as polycythemia rubra vera, chronic myeloid leukemia, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, idiopathic myelofibrosis, chronic eosinophilic leukemia and the hypereosinophilic syndrome, acute and chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphoma. Patients with aggressive SM (ASM)16 frequently have evidence of impaired liver function, hypersplenism, and/or malabsorption, but they do not have a distinctive hematologic disorder or mast cell leukemia (MCL). Patients with ASM have rapidly increasing mast cell numbers and are difficult to manage medically. MCL is characterized by multiorgan failure, and in bone marrow smears mast cells represent greater than 20% of the nucleated cell population. Mast cells also account for 10% or more of peripheral blood nucleated cells.17,18 Mast cell sarcomas are rare; they have localized destructive growth, and distant spread is possible. Mast cells in these tumors are highly atypical and immature. Extracutaneous mastocytomas are extremely rare, usually localized to the lung, and consist of mature mast cells.3,19

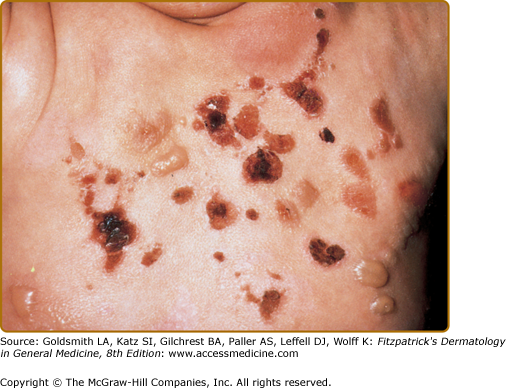

UP is the most common skin manifestation of CM; however, the morphology of UP lesions differs significantly between children and adults. UP lesions in children appear as tan to brown papules and less commonly as macules, ranging in size from 1.0 to 2.5 cm in diameter (Fig. 149-1). These lesions may be present at birth or arise during infancy. They frequently appear on the trunk and often spare the central face, scalp, palms, and soles. UP lesions in adults, on the other hand, are reddish-brown macules and papules, usually 0.5 cm or less in diameter (Fig. 149-4). On close lesion inspection, variable hyperpigmentation and fine telangiectasias are detectable. Adult UP lesions are most numerous on the trunk and proximal extremities and appear less frequently on the face, distal extremities, or palms and soles. While adult UP lesions appear and resolve over months in individual patients, their number usually increases over years.20 UP lesions are seen in most adults with ISM, but are much less common in patients with SM-AHNMD, ASM, or MCL.3,19,20

Solitary mastocytomas are tan-brown nodules that occur in approximately 10%–35% of children and frequently appear on the distal extremities (Fig. 149-2).11 Their onset is generally before 6 months of age.2 Trauma to mastocytomas has been associated with systemic symptoms such as flushing and hypotension (Fig. 149-1).2,20

Scratching or rubbing lesions of CM leads to urtication and erythema known as Darier’s sign. This reaction is readily demonstrated in childhood UP lesions and mastocytomas, but often is less apparent in adult UP lesions.20 This likely explanation is that mast cell concentrations in mastocytomas and childhood UP have been reported to be 150-fold and 40-fold greater than normal skin, respectively, whereas the mast cell content of lesional skin in adult mastocytosis patients was only eightfold greater than normal controls.21

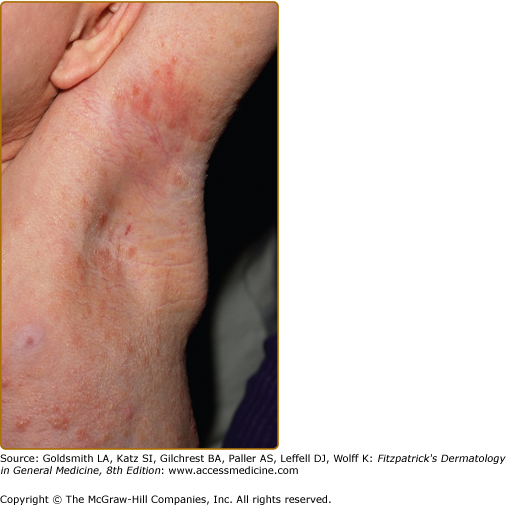

Diffuse CM (DCM) is seen almost exclusively in infants (Fig. 149-3), although it may persist into adult life. The skin may be thickened with a peau d’orange appearance and yellowish brown discoloration without discrete lesions. Dermographism with formation of hemorrhagic blisters frequently occurs in the first few years of life in patients with DCM, but these blisters often resolve within several years, even though the DCM may persist (Fig. 149-5).2,20 Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans is rare, and is seen almost exclusively in adults. It appears as telangiectatic macules with irregular borders (Fig. 149-6). Darier’s sign and pruritus is variable.20 Recently, nodular mastocytosis has been described in an adult patient with red–purple lesions infiltrating the axillae and inguinal areas. Mast cells in this rare variant of mastocytosis expressed the V560G c-kit mutation.22

Most children with CM and adults with ISM have few, if any, symptoms. When symptoms do occur, they are due to the release of mast cell mediators, such as histamine, eicosanoids, and cytokines (Table 149-3). Symptoms and signs of mastocytosis may range from pruritus and flushing to abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, palpitations, dizziness, and syncope. Of interest is the relative absence of pulmonary symptoms in mastocytosis patients. Complaints of fever, night sweats, malaise, weight loss, bone pain, epigastric distress, and problems with mentation (cognitive disorganization) often signal the presence of SM. Symptoms of mastocytosis can be exacerbated by exercise, heat, or local trauma to skin lesions (childhood UP and mastocytomas). In addition, alcohol, narcotics, salicylates, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), polymyxin B, anticholinergics, and some systemic anesthetic agents may induce mast cell mediator release.19,20,23 Deaths associated with extensive mast cell mediator release are rare.

Mediators | Biologic Effects | Possible Consequences |

|---|---|---|

Preformed | ||

Histamine | Vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, gastric hypersecretion, bronchoconstriction | Hypotension, flushing, urticaria, abdominal pain; (peptic, colic), nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, malabsorption |

Heparin | Anticoagulant, inhibition of platelet aggregation | Prolonged bleeding time |

Tryptase | Endothelial cell activation, fibrinogen cleavage, mitogenic for smooth muscle cells | Osteoporosis/osteopenia, disruption of cascade systems (clotting, etc.) |

Chymase | Converts angiotensin I to II, lipoprotein degradation Cleaves membrane bound stem cell factor | Hypertension Hyperpigmentation, Skin mast cell accumulation (?) |

Newly Synthesized | ||

Leukotrienes | Increased vascular permeability, bronchoconstriction, vasoconstriction | Bronchospasm, hypotension |

Prostaglandins | Vasodilatation, bronchoconstriction | Flushing, urticaria, hypotension |

Cytokines |