23 Management of patients with exfoliative disorders, epidermolysis bullosa, and TEN

Synopsis

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS), SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN can be considered as a continuum of the same disease spectrum, with increased total body surface area and mucosal involvement.

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS), SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN can be considered as a continuum of the same disease spectrum, with increased total body surface area and mucosal involvement.

These exfoliative skin disorders are drug-induced in more than 50% of patients.

These exfoliative skin disorders are drug-induced in more than 50% of patients.

Sulfonamides, anticonvulsants, some antibiotics as well as acetaminophen are some of the well-documented drugs associated with SJS and TEN.

Sulfonamides, anticonvulsants, some antibiotics as well as acetaminophen are some of the well-documented drugs associated with SJS and TEN.

Detailed history of recent medications is essential.

Detailed history of recent medications is essential.

These conditions may have significant morbidity and mortality if not managed aggressively and early.

These conditions may have significant morbidity and mortality if not managed aggressively and early.

The mainstay of management is early wound debridement, irrigation, and coverage with skin substitute.

The mainstay of management is early wound debridement, irrigation, and coverage with skin substitute.

Contractures and hypertrophic scarring are frequent long-term complications that may need revisions.

Contractures and hypertrophic scarring are frequent long-term complications that may need revisions.

Ocular complications are also very common and early involvement of ophthalmology is crucial.

Ocular complications are also very common and early involvement of ophthalmology is crucial.

Epidermolysis bullosa

Epidermolysis bullosa is a blistering skin condition resulting from defects in the anchoring system of epithelial tissue in the basement membrane.

Epidermolysis bullosa is a blistering skin condition resulting from defects in the anchoring system of epithelial tissue in the basement membrane.

It is characterized by the development of fluid-filled blisters secondary to trauma.

It is characterized by the development of fluid-filled blisters secondary to trauma.

Skin biopsies, electron as well as immunofluorescent microscopy are essential for diagnosis.

Skin biopsies, electron as well as immunofluorescent microscopy are essential for diagnosis.

Adequate nutritional support is important to facilitate wound healing.

Adequate nutritional support is important to facilitate wound healing.

Meticulous skin care is required to prevent further injuries to the skin.

Meticulous skin care is required to prevent further injuries to the skin.

These patients present to the plastic surgeon with chronic nonhealing wounds, scar contractures, or syndactalysed digits from repeated scarring.

These patients present to the plastic surgeon with chronic nonhealing wounds, scar contractures, or syndactalysed digits from repeated scarring.

Squamous cell carcinoma is a well-documented long-term complication in these patients with chronically healing wound.

Squamous cell carcinoma is a well-documented long-term complication in these patients with chronically healing wound.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis

Historical perspective

In 1956, Lyell1 reported his observations of four patients who developed an acute, febrile, and toxic illness characterized by epidermal necrosis, which proceeded to eventual detachment and slough of large sheets of epidermis. Lyell named this syndrome toxic epidermal necrolysis or TEN. TEN is the most extensive form of a group of exfoliative disorders of the skin that include erythema multiforme and SJS, both of which are characterized by detachment of the epidermis from the dermis.2–5

Historically, TEN was treated by dermatologists. However, plastic surgeons, especially those who routinely deal with patients who have sustained extensive skin loss from large burn injuries, are now frequently involved in the care of patients with TEN. As early as 1978, it was recognized that burn units provide expertise in the care of critically ill patients with large areas of skin loss and are ideally suited to care of patients with TEN.6–9 The authors’ regional adult burn center began to admit patients with TEN in 1995. To date, the center has treated over 40 patients with TEN, which represents one of the largest single-institution experiences with this disease entity in North America. The burn center originally became involved in the care of these patients because of the expertise of the nurses in dealing with large open wounds. Since then, a complete burn team approach to patients with TEN has evolved which includes standardized wound management, aggressive critical care support, nutrition, rehabilitation therapy, family and social support, and prevention. It is firmly believed that TEN is best managed in a burn care facility led by surgeons who routinely deal with patients with large cutaneous burns. This chapter provides the reader with a complete review of the current concepts on TEN as well as an individualized approach to the care of patients with this complex and challenging disease.

Basic science/disease process

Whereas the exact pathogenesis of SJS and TEN remains unknown, evidence has accumulated to suggest that the patients who develop SJS or TEN have aberrant metabolism of the culprit drug and altered detoxification of reactive drug metabolites. This has been most extensively studied in patients who developed TEN from sulfonamides or anticonvulsants.10–15 It is believed that reactive drug metabolites then induce a cell-mediated cytotoxic immune response against the epidermis.16–19 CD8+ T lymphocytes and macrophages appear within the epidermis16–19 and are believed to mediate this autoimmune response. Cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (which has been found in TEN blister fluid) probably contribute to epidermal cell injury as well.4,20 Apoptosis, which is essentially an activation of a genetic program that leads to cell death, appears to be the final common pathway of keratinocyte death in TEN and SJS–TEN overlap.21 The keratinocyte apoptosis in TEN appears to be activated by an interaction between the death receptor Fas (CD95), normally found on keratinocytes, and active Fas ligand (FasL or CD95L), abnormally produced by keratinocytes in patients with TEN.22 This is a particularly exciting finding because the Fas–FasL interaction can be blocked by antibodies found in intravenous immune globulin,22 leading to a potential therapeutic intervention for TEN.22 In early SJS and TEN, patchy necrosis of keratinocytes is seen at the dermal–epidermal junction. Later, the necrosis extends throughout the epidermis, and detachment of the epidermis from the dermis is noted. The underlying dermis is essentially normal with only sparse dermal infiltrate of helper T lymphocytes.20,23

Patient presentation/diagnosis

Erythema multiforme is a cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction usually associated with an infection, such as recurrent herpes simplex or Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection.23,24 Erythema multiforme is subclassified as minor or major. Erythema multiforme minor is characterized by the appearance of dusky, erythematous “target” or “iris” lesions, sometimes with blisters or bullae, symmetrically distributed on the extensor surfaces of the limbs and on the palms and soles.23,24 Erythema multiforme major features are a similar picture, but mucosal surfaces, usually the mouth, are involved with erosions as well.24

SJS was originally described in two children who presented with aggressive disseminated cutaneous eruptions, severe stomatitis, and conjunctivitis.25 As a result of the apparent similarity with erythema multiforme major, SJS was thought to be a variant of it. However, SJS is distinct from erythema multiforme major and should be classified separately. Erythema multiforme major is caused by an infection, features characteristic target-like lesions in a symmetric acral distribution, and has low morbidity and no associated mortality. SJS is drug-induced, features more widespread and central areas of skin involvement with epidermal detachment, and has high morbidity and occasional mortality.20

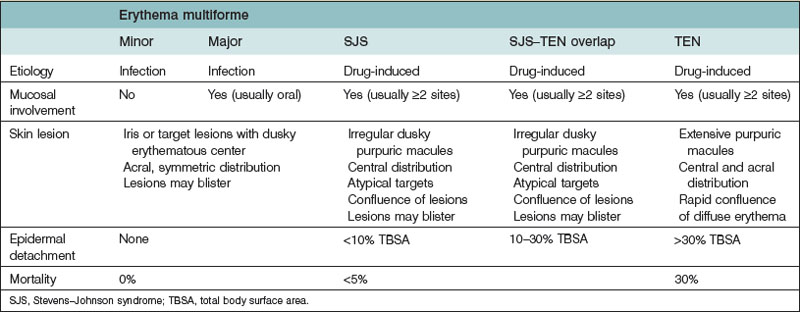

TEN, like SJS, features mucosal involvement and is a severe drug-induced exfoliative disorder of the skin. Currently, SJS and TEN are considered to be variants of the same drug-induced process and probably exist on a spectrum, with TEN being the more severe form of the same process.4,20,26,27 The current consensus is that the diagnosis of SJS is given to patients with mucosal involvement, widespread purpuric macules, and epidermal detachment involving less than 10% of the total body surface area. SJS–TEN overlap applies to patients with mucosal involvement, widespread purpuric macules, and epidermal detachment involving 10–30% of the total body surface area. The diagnosis of TEN is applied to those patients with widespread purpuric macules, mucosal involvement, and epidermal detachment involving more than 30% of the total body surface area (Table 23.1).4,20,24,28

Patients with SJS, SJS–TEN, and TEN are relatively rare. The incidence of SJS ranges from 1.2 to 6 patients per million per year.4 The incidence of TEN is estimated to range from 0.4 to 1.9 patients per million per year.29–33 However, it is recognized that TEN is probably an underreported disease entity. SJS and TEN have been observed worldwide in all human populations.13 Whereas SJS is considered to be a drug-induced reaction, a causative drug is found in only about 50% of those patients with the disease.4 This probably reflects erroneous diagnosis of SJS as erythema multiforme major. In TEN, a causative drug is identified in approximately 80% of patients, and less than 5% have no associated drug use.34,35

The drugs most commonly implicated in SJS and TEN are the sulfonamides (co-trimoxazole), the anticonvulsants (phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine), some antibiotics (aminopenicillins, quinolones, cephalosporins), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and allopurinol.36 However, many other drugs have been associated with the onset of SJS and TEN, including common antipyretics such as acetaminophen and acetylsalicylic acid.26 Although no reliable test exists to prove the association between a specific drug and the onset of TEN,26,37 the lymphocyte toxicity assay (LTA) shows promise. The LTA is based on the concept that reactive metabolites of certain drugs are implicated in TEN.10 The LTA exposes the patient’s lymphocytes in vitro to a drug in the presence of a metabolizing system. Cytotoxic effect is used as evidence of increased sensitivity to newly formed toxic metabolites from the drug.38–40 The LTA has been used to confirm sensitivity to anticonvulsants in a patient with TEN treated at the authors’ facility who had been receiving both anticonvulsants and cephalosporins.41 The LTA has the potential to test not only the patient but also first-degree relatives of the patient for the likelihood of a similar adverse drug reaction. Hence, the LTA offers enormous possibilities in prevention of the disease in patients and their families. It has been shown that there is a very strong association of SJS–TEN with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B 5801 and allupurinol as well as HLA-B 1502 and carbamazepine in the Chinese population. This association was not as strong in the European population. The Food and Drug Administration has recommended genotyping all Asian Patients for HLA-B 1502 before starting carbamazepine.42,43 However, at present, implication of a drug in the pathogenesis of SJS or TEN relies on obtaining a careful history of the patient’s drug use with the recognition that most instances of TEN arise within 1–3 weeks of starting the causative drug.20,44,45 Nonetheless, TEN may develop with use of a drug outside this range. For example, SJS and TEN have been significantly associated with up to 8 weeks of use of phenytoin, phenobarbital, and carbamazepine.46 Some medical conditions may be associated with an increased risk of TEN. These include systemic lupus erythematosus,31 recent bone marrow transplantation,47,48 and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.49–52 TEN is more common in the elderly, but this may only reflect greater use of medications in this group.3,23

The cutaneous manifestations of TEN are typically preceded by a 2–3-day prodrome of what appears to be influenza or an upper respiratory tract infection. Patients initially have fever and malaise, and they experience pharyngitis or conjunctivitis. The skin may become pruritic. After this prodrome, dusky erythematous macules appear on the skin, usually on the trunk and face initially and then spreading to the extremities. These macules may be target-like but more often are irregular and ill defined. Blisters or bullae may appear within these macules. Within 3 or 4 days (but occasionally within hours) of the onset of these skin lesions, confluence of the macules into diffuse erythema develops, large bullae appear, and extensive sheets of epidermis begin to detach (Fig. 23.1), leaving raw areas of glistening bright red dermis exposed (Fig. 23.2). The Nikolsky sign, although nonspecific, is present in the spectrum of SJS and TEN (Fig. 23.3). This sign refers to the immediate detachment of the epidermis with lateral digital pressure on the skin in the areas where confluent erythema is present. Mucosal involvement is usually advanced by this stage and involves blistering, slough, and erosion of mucosal surfaces (Fig. 23.4). The lips and oral pharynx are most commonly involved, followed by the conjunctiva, genital mucosa, and anorectal mucosa. Mucosal sloughing may also involve the esophagus, the remainder of the gastrointestinal tract, and the tracheobronchial surfaces.53,54

Involvement of the lips and oropharynx can be particularly aggressive, with severe pain, dysphagia, odynophagia, and bleeding. The lips typically become crusted. Similarly, ocular involvement is also usually severe. Pseudomembranous conjunctival erosions may result in the formation of synechiae between the lids or between the conjunctiva and the eyelids.8,45

Laboratory abnormalities on presentation may include anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and abnormal indices of renal and hepatic functions.45 As a consequence of extensive areas of skin loss, the patient may develop problems related to fluid loss, hypothermia, and invasive infection. Prerenal azotemia, urosepsis, bronchopneumonia, and sepsis commonly occur.9,23,45,55–58 The most common infective organisms appear to be Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas species, and Acinetobacter species.20,37,59 Mortality is most commonly the result of sepsis and multiple organ failure.9,55,57–61

Assuming the patient survives and the dermis is not secondarily injured by desiccation, infection, or mechanical trauma (e.g., pressure), re-epithelialization proceeds within a few days and is complete within 3 weeks.8,20 Mucosal surfaces may remain eroded and crusted for several more weeks.

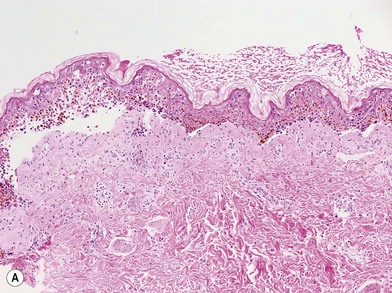

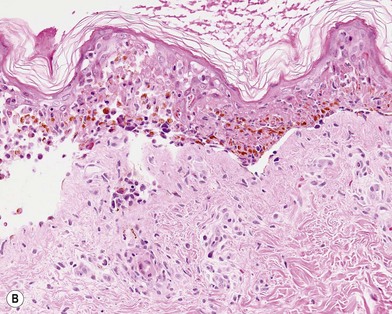

Although the diagnosis of SJS–TEN is usually clear, a biopsy should be performed to confirm the diagnosis (Fig. 23.5).20,23,62 Important exfoliative disease entities to be distinguished from TEN include staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome, pemphigus, pemphigoid, scarlet fever, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, toxic shock syndrome, and unrecognized scald injuries in comatose patients.4,20,23

Staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome is probably the most common condition to masquerade as TEN. It is of interest that Lyell’s 1956 description of TEN probably included a patient with staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome.1,20,62 Staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome usually occurs in children and never has target lesions, and oropharyngeal involvement is uncommon. A biopsy easily differentiates the intraepidermal split within the granular layer in staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome from the dermal–epidermal split in TEN.62

Patient selection

General

Burn units are ideally suited to the care of patients with large areas of skin loss. Thus, whereas patients with erythema multiforme or SJS may not qualify, those with more severe SJS–TEN overlap or TEN should be referred to a burn center.6–9,55,59,60 Familiarity with the care of large open wounds, nursing expertise, and aggressive critical care are important advantages that a burn treatment facility can offer to a patient with TEN. Early referral to a burn center (i.e., within 3–7 days of onset of skin slough) has been found to reduce mortality and hospital length of stay in patients with TEN.9,57–60,63

Treatment/surgical technique

ABCs

In a prospective study of pulmonary complications in SJS–TEN overlap and TEN patients, significant involvement of the respiratory system at presentation was noted in 24% of patients.64 Patients may be at risk for acute upper airway obstruction from excessive secretions, bleeding, or edema.64,65 Alternatively, the patient may present with severe dyspnea or hypoxemia from bronchopulmonary desquamation, established bronchopneumonia, or evolving acute respiratory distress syndrome.2,64 Therefore, careful consideration should be given to the need for intubation and mechanical ventilatory support. This must be counterbalanced with the recognition of the potential risk for ventilator-associated pneumonia in this group of patients.

Intubation of these patients may be extremely difficult because of mucosal sloughing, swelling, and bleeding in the upper airway. Intubation should be done by a physician experienced in dealing with the difficult airway. The airway is best secured with ties around the neck or by wiring the endotracheal tube to the dentition. Adhesive tape should not be used because it will not securely stick to the skin and may peel off facial and neck epidermis. If the endotracheal tube is wired, wire cutters must be immediately available at the bedside. It is recommended that TEN patients who are intubated undergo immediate fiberoptic bronchoscopy. This is done to assess the state of the tracheobronchial mucosa and to obtain bronchoalveolar lavage specimens for immediate Gram stain and then culture and sensitivity testing. Bronchial mucosal detachment identified at early fiberoptic bronchoscopy appears to indicate a poor prognosis.64

Although patients with TEN do not experience the massive fluid shifts that would occur in a patient with comparable second-degree burns, early attention must also be given to fluid and hemodynamic support. Peripheral intravenous access is preferred to avoid the infective risks associated with central access. However, the difficulty in finding and then securing a peripheral intravenous site in a patient with widespread exfoliation often necessitates a central line. Crystalloid fluid replacement may be necessary to reverse dehydration from inadequate oral intake due to severe stomatitis or from insensible fluid losses from open wounds. Some patients may present with established sepsis and may require more aggressive fluid and vasopressor support58 and invasive monitoring.

Wound care

Dermal protection is the primary goal in the care of the wounds that result from exfoliation of the epidermis and is exactly analogous to the care of a superficial partial-thickness burn. Unimpeded re-epithelialization will occur as long as this goal is achieved. Desiccation, shear, pressure, and infection must be avoided. An early surgical approach is advocated in which the sloughing sheets of epidermis are removed, the raw dermal wounds are cleaned and irrigated, and the wound is covered with a temporary biologic or biosynthetic dressing.8,9,55,57–60 Areas not involved with slough or imminent slough are left intact until such time as confluent epidermal detachment develops. During wound irrigation and debridement, caustic detergents should be avoided. Tap water from a hydrotherapy shower cart combined with chlorhexidine soap or, occasionally, bacitracin solution may be used. The choice of temporary skin substitute varies among institutions. In a multicenter survey of burn units that treat TEN patients,57 Biobrane (Dow B Hickam, Sugarland, TX) was the most commonly used skin substitute, followed by porcine xenograft and cadaveric allograft.

Application of a skin substitute to the raw dermis provides protection, minimizes fluid electrolyte and heat loss from the wound, reduces exogenous bacterial invasion of the wound, reduces pain, and facilitates movement of the underlying parts (Fig. 23.6). Regardless of the choice of substitute, the key principle is meticulous removal of the epidermis, irrigation and cleaning of the wound, and fixation of the substitute with sutures or staples. The substitute of choice is Biobrane.66,67 Biobrane is preferable because it is inert, relatively inexpensive, available off the shelf, and transparent, which allows inspection of the wound through the material. Involved skin areas that have not yet begun to slough are treated with a nonadherent tulle gauze layer, covered with gauzes soaked in a topical antimicrobial solution, changed twice a day. Effective antimicrobial solutions include silver nitrate,2,3,68 chlorhexidine gluconate solution,3 and polymyxin-bacitracin.69 Topical 5% mafenide acetate (Sulfamylon) and topical silver sulfadiazine cream (SSD) have been used,57 but the unknown risk of sulfonamide cross-reactivity in a TEN patient makes the use of silver sulfadiazine cream a less suitable choice. A 5% mafenide acetate solution is preferred because it is clear and colorless and because of its broad-spectrum coverage abilities.

Drug withdrawal and the issue of corticosteroids

When the drug causing SJS or TEN is known, it should be immediately withdrawn. Evidence from a retrospective study involving 113 patients with SJS or TEN suggests that prognosis is improved by earlier withdrawal of the causative drug.70

The issue of corticosteroid therapy remains highly controversial. Use of corticosteroids has been recommended early in the course of the disease71,72 in an effort to reverse inflammation and progression to skin sloughing. However, the effectiveness of this strategy has never been demonstrated in a clinical trial. TEN has developed in patients already receiving corticosteroids for other diseases,73 suggesting that corticosteroids do not prevent or limit progression of TEN. A multicenter survey of TEN treated in US burn centers found that treatment with steroids before admission did not improve survival.57 Retrospective data involving patients with SJS and TEN treated in burn centers revealed that survival rates were significantly lower in patients who received high-dose corticosteroids.9,68 Although all of the evidence is retrospective, steroids do not appear to improve prognosis in SJS and TEN and may actually worsen morbidity and mortality. Hence, their use is not recommended, especially in patients who have significant skin slough (SJS–TEN overlap and TEN). A careful drug use history should be obtained and the suspected inciting drugs should be immediately withdrawn. This may require substitution with an alternative drug, for example, when an anticonvulsant is implicated. If corticosteroids were started before admission, these should be stopped or rapidly tapered over 48–72 hours.