IN THIS CHAPTER

- •

Introduction 217

- •

Patient selection 217

- •

Preoperative history and considerations 222

- •

Operative approach 223

- •

Postoperative care 224

Pre-existing abdominal scars can have a significant impact on the safety and final result of abdominoplasty and abdominal contouring procedures. These scars should be judiciously taken into account during the evaluation and planning process. Although safety is the primary focus, pre-existing abdominal scars are not an absolute contraindication to abdominoplasty when the procedure is properly planned and designed. With proper design modification, good aesthetic results can be safely achieved in patients with pre-existing abdominal scars.

Introduction

Abdominal incisions are commonly used for the majority of general, gynecologic, oncologic, urologic, and other surgical operations. Because of this, abdominal scars are frequently encountered in patients presenting for abdominoplasty and abdominal body contouring. Although laparoscopic surgery has reduced the length of the scars associated with many of these common procedures, large surgical scars across important soft-tissue vascular territories are often still encountered. Fortunately, many of these pre-existing scars fall within the area of resection for standard abdominoplasty procedures.

Large scars that do not fall within the abdominoplasty resection segment require careful evaluation and modification of the standard abdominoplasty design. The presence of such scars should not serve as an absolute contraindication to abdominoplasty and abdominal contouring procedures: instead, thoughtful planning should allow a modified design to be tailored to each individual patient so as to reduce the incidence of complications, particularly ischemia and necrosis, and safely achieve the best possible aesthetic result.

Introduction

Abdominal incisions are commonly used for the majority of general, gynecologic, oncologic, urologic, and other surgical operations. Because of this, abdominal scars are frequently encountered in patients presenting for abdominoplasty and abdominal body contouring. Although laparoscopic surgery has reduced the length of the scars associated with many of these common procedures, large surgical scars across important soft-tissue vascular territories are often still encountered. Fortunately, many of these pre-existing scars fall within the area of resection for standard abdominoplasty procedures.

Large scars that do not fall within the abdominoplasty resection segment require careful evaluation and modification of the standard abdominoplasty design. The presence of such scars should not serve as an absolute contraindication to abdominoplasty and abdominal contouring procedures: instead, thoughtful planning should allow a modified design to be tailored to each individual patient so as to reduce the incidence of complications, particularly ischemia and necrosis, and safely achieve the best possible aesthetic result.

Patient Selection

Patients seeking abdominal contouring procedures can present with a variety of existing abdominal scars. The significance of these is based on many factors, including size and location of the scar, the amount of abdominal soft-tissue laxity, and the desired aesthetic goal. To simplify the evaluation process as well as selection of the appropriate abdominoplasty procedure, we have categorized those patients whose scars require little modification of the abdominoplasty design as category I, and those that require fundamental design alteration as category II ( Table 14.1 ). As with most categorizations, some patients fall somewhere in between the groups. Nevertheless, this is an initial step in the evaluation and management of these patients and aids efficient communication among surgeons.

| Category | Scar location/Impact on the abdominoplasty design |

|---|---|

| I | The scar generally falls within the soft-tissue segment that is resected during a standard abdominoplasty (midline, Pfannensteil, or right/left lower quadrants). Little or no modification of the standard technique is needed |

| IIA | The subcostal scar (unilateral or bilateral) is near the costal margin. Traditional full abdominoplasty techniques will risk ischemia of the tissue immediately caudal to the scar(s). A reverse abdominoplasty or a lower abdominoplasty (or a staged procedure with both a reverse abdominoplasty and a lower abdominoplasty) can safely be used to resect excess soft-tissue laxity |

| IIB | The subcostal scar is some distance below the costal margin, either by original design or secondary to soft-tissue descent. Neither a reverse abdominoplasty nor a traditional abdominoplasty can incorporate this scar. A full or circumferential abdominoplasty with a vertical or oblique segment can be used to remove the tissue medial and caudal to the scar that is at highest risk for ischemia. This procedure design is not a safe option for patients in this category who have bilateral subcostal (chevron) scars. A reverse abdominoplasty, either alone or staged with a lower abdominoplasty, is recommended, accepting the fact that the final scar will near the mid-abdomen at the level of the previous scar. |

The most common abdominal scars seen are those following laparoscopic surgery. These are usually between three and five in number, between 2 and 4 cm in length, and do not significantly affect the vascular perfusion of the abdominal skin. The traditional ‘open’ surgical approaches to the abdomen have a greater potential to negatively affect the safety and/or final result of an abdominoplasty procedure. Fortunately, the more common ‘open’ procedures usually result in a scar in the lower abdomen. These include the traditional right lower quadrant appendectomy approach, infraumbilical midline laparotomy, and the suprapubic Pfannensteil incision ( Fig. 14.1 ). Although some caution is warranted in these cases owing to the potential presence of excess scar tissue and abdominal wall incisional hernia, little modification of the standard abdominoplasty technique is usually needed, as these scars usually fall within the soft-tissue segment that is resected. A similar group of patients are those with pre-existing supraumbilical midline scars ( Fig. 14.2 ). Because these scars are in the watershed area of the left and right intercostal and subcostal perforators, they are often easily incorporated into standard abdominoplasty techniques. A simple scar revision may be necessary if there is a scar band contracture, or a more sizeable vertical resection can be added if deemed beneficial to the final aesthetic result ( Fig. 14.3 ). Patients presenting with these types of scars are classified as category I, as little modification of the standard abdominoplasty procedure is needed.

Abdominal scars that cross important vascular territories and that cannot be incorporated into the resected soft-tissue segment are of greater concern. These include unilateral subcostal incisions (Kocher) or bilateral subcostal incisions connected in the midline (chevron). Patients with these types of scar are classified as category II, as they require significant alteration of the standard abdominoplasty design in order to prevent ischemic complications. These patients can be further subclassified according to the position of the scar relative to the costal margin, because this will in part determine the type of abdominoplasty modification needed. Category IIA patients have subcostal scars that are very close to the costal margins, whereas category IIB patients have subcostal scars some distance below the costal margin, either by design or as a result of caudal migration secondary to increasing soft-tissue laxity. This distinction is important, because the abdominoplasty procedures best suited for each of these subgroups are fundamentally different ( Table 14.1 ).

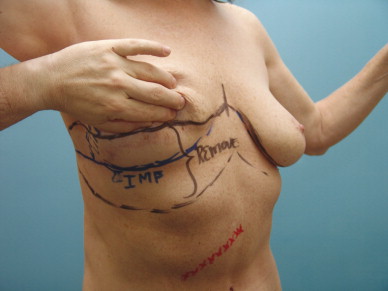

Category IIA patients (subcostal scar(s) at or near the costal margin) are at significant risk for ischemia of the abdominal soft tissue immediately distal to the scar ( Fig. 14.4 ). The two general options to remove excess soft-tissue laxity in these patients are either a lower abdominoplasty with limited undermining or a reverse abdominoplasty. A lower abdominoplasty is ideally suited for patients with isolated lower abdominal soft-tissue excess. An example of this is the mini abdominoplasty patient (see Chapter 5 , Mini Abdominoplasty). The superficial circumflex vessels and the perforators from the deep epigastric arcade above the umbilicus can be preserved to provide perfusion to the soft-tissue segment immediately caudal to the subcostal scar (see Chapter 2 , Anatomic Considerations in Abdominal Contouring). Limited undermining to preserve perforators medial to the existing scar is also recommended to maintain the viability of the abdominal flap. Similarly, a reverse abdominoplasty can be performed for category IIA patients to remove some of the upper abdominal soft-tissue laxity ( Fig. 14.5 ). Depending on the amount of laxity and the distance of the scar from the inframammary fold, the resection segment of a reverse abdominoplasty may incorporate the subcostal scar.

It is important to note that with a standard reverse abdominoplasty procedure the final scar should ideally be at the inframammary fold ( Fig. 14.6 ). Although this is also the goal of reverse abdominoplasty in category IIA patients, it may be harder to accomplish because the final location of the scar is in part determined by the location of the existing scar. If there is insufficient soft-tissue laxity to enable the skin between the subcostal scar and the inframammary fold to be removed, the final abdominoplasty scar will be placed below the inframammary fold, and this must be pointed out to the patient. Thorough discussion with the patient about these issues will permit them to make an informed decision about the type of abdominal contouring procedure and the type of scar they would prefer to have.

Both the lower and the reverse abdominoplasty procedures individually will help to correct a moderate amount of soft-tissue laxity. For category IIA patients who have more significant soft-tissue laxity, a lower abdominoplasty and a reverse abdominoplasty may be performed in staged fashion to accomplish the desired aesthetic goal safely. The decision to stage these patients is determined largely by the amount of soft-tissue laxity and the amount of correction desired.

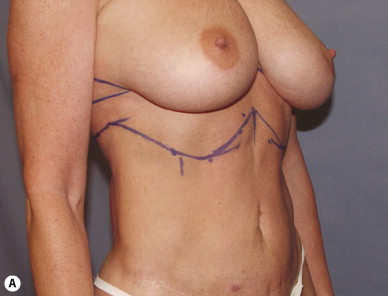

Category IIB patients (subcostal scar(s) an appreciable distance caudal to the costal margin) may not be good candidates for either lower or reverse abdominoplasty ( Fig. 14.7 ). Both of these options often affect only a small portion of the abdominal soft-tissue excess and leave a very poorly positioned scar (positioned too high with lower abdominoplasty, and too low with reverse abdominoplasty). The scars, however, are highly amenable to a formal abdominoplasty with the vertical resection encompassing the scar and tissue medial to it, with minimal risk of ischemia and/or necrosis.

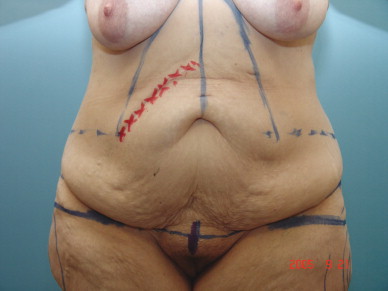

Most category IIB patients have caudally located subcostal scars because of gravitational migration secondary to significant soft-tissue laxity. When significant soft-tissue laxity is present in category IIB patients, the addition of a vertical or oblique elliptical resection to a standard abdominoplasty should be strongly considered, as this will allow the scar and the tissue medial to the scar, at risk for ischemia, to be incorporated within the vertical resection. The goal is to remove all of the excess soft-tissue laxity medial to the subcostal scar. If there is significant laxity the subcostal scar can be incorporated in the resection segment and the vertical final scar can still be placed at or near the midline ( Fig. 14.8 ). In some patients, however, the size and location of the scar as well as the amount of soft-tissue laxity makes this difficult to accomplish safely. Instead, the dissection and resection are performed asymmetrically to preserve more perforators on the side of the existing scar. This results in a final ‘vertical’ scar that is oblique, with a position inferior to and sometimes paralleling the path of the previous subcostal scar ( Fig. 14.9 ).