IN THIS CHAPTER

- •

Introduction 229

- •

Seroma 229

- •

Hematoma 232

- •

Cellulitis 232

- •

Pseudo-Bursa 233

- •

Dog-Ears 234

- •

Scar placement 236

- •

Umbilical complications 237

- •

Ischemia 237

- •

Necrosis 238

- •

Infection 239

- •

Suture extrusion 240

- •

DVT/PE 240

Complications of abdominoplasty are usually minor and may include poor scars, lateral dog-ears, or suture extrusions. More significant complications may include persistent seroma, pseudo-bursae, and small areas of ischemia and wound healing problems. The most worrisome complications are those that are life-threatening or that severely affect the final aesthetic result. These may include large hematomas, significant infection, necrosis, and DVT/PE. The primary goal with all potential complications is to take the proper steps to prevent them. When complications do occur, however, it is important for the surgeon to diagnose the problem accurately and institute the necessary measures to minimize the deleterious effect of the complication and allow the patient to return to the path of healing.

Introduction

Reducing the incidence of complications is an important focus for all surgical procedures. This is especially the case with cosmetic procedures, where relatively healthy and functionally normal patients undergo elective surgery to improve their appearance. Patient selection, preoperative screening, selection of the appropriate surgical procedure, and good surgical technique are all important in avoiding or reducing the incidence of complications. Equally important for overall patient satisfaction, safety, and the final aesthetic result is the proper diagnosis and management of complications when they do occur. As with all problem-solving situations, identifying the existence of the problem, correct diagnosis, and appropriate treatment are all necessary to accomplish this.

For both the surgeon and the patient, the magnitude of complications can range from simple nuisance to potentially lethal. This chapter will address the more common as well as the more significant complications that can occur with abdominoplasty and abdominal contouring procedures. The intention is to provide information that will be useful for the surgeon performing the procedures discussed in this book.

Introduction

Reducing the incidence of complications is an important focus for all surgical procedures. This is especially the case with cosmetic procedures, where relatively healthy and functionally normal patients undergo elective surgery to improve their appearance. Patient selection, preoperative screening, selection of the appropriate surgical procedure, and good surgical technique are all important in avoiding or reducing the incidence of complications. Equally important for overall patient satisfaction, safety, and the final aesthetic result is the proper diagnosis and management of complications when they do occur. As with all problem-solving situations, identifying the existence of the problem, correct diagnosis, and appropriate treatment are all necessary to accomplish this.

For both the surgeon and the patient, the magnitude of complications can range from simple nuisance to potentially lethal. This chapter will address the more common as well as the more significant complications that can occur with abdominoplasty and abdominal contouring procedures. The intention is to provide information that will be useful for the surgeon performing the procedures discussed in this book.

Seroma ( Box 15.1 )

Technically speaking, ‘seroma’ formation is an inherent part of the healing process following abdominoplasty procedures. Seroma as a complication is more accurately defined as any collection of fluid that requires repeated percutaneous drainage, is clinically detectable, and/or affects the final aesthetic result. Many factors have been theoretically attributed to an increased incidence of seroma. In essence, any factor that increases or prolongs the postoperative inflammatory process theoretically increases the chance of seroma. Examples include intraoperative bleeding, excess use of electrocautery, and additional soft-tissue trauma due to concurrent liposuction. Many factors play a role in seroma formation of which we are unaware or cannot confidently identify. Some of these may be patient specific and related to anatomy, physiology, or the presence of certain comorbid conditions.

- •

The formation of seroma fluid is an inherent part of the healing process following an abdominoplasty

- •

Seroma as a complication is better defined as any clinically detectable fluid that requires repeated or continuous drainage

- •

The most common site for seroma fluid accumulation is in the midline below the umbilicus, and there may be fullness or a noticeable fluid wave on examination

- •

Percutaneous aspiration under sterile conditions should be performed at least twice weekly until fluid accumulation ceases. The abdominal binder should be worn continuously (day and night) during this time

- •

The aspirate should be sent for culture if there is any suspicion of infection

Minimizing soft-tissue trauma is an important component of seroma prevention. Meticulous surgical technique and proper dissection using an electrocautery setting that is low yet efficient will help minimize the extent of soft-tissue damage. The additional thermal damage to the surrounding soft tissue that occurs with high electrocautery settings is unnecessary and one potential source of increased seroma formation.

Concurrent use of liposuction during abdominoplasty to thin the abdominal soft-tissue apron is common (see Chapter 3 , Liposuction in Abdominal Contouring). Although this is a highly useful adjunct in patients with excess adiposity, it does result in a larger surgical surface area. The additional soft-tissue trauma created by the liposuction cannula, as well as the residual tumescent fluid that remains at the end of the procedure, may explain the increased incidence of seroma formation in abdominoplasty procedures when concurrent liposuction is used. The use of smaller-diameter cannulas and proper tumescent infiltration can help minimize the additional trauma.

Proper removal of residual tumescent fluid in the immediate postoperative period is helpful in allowing the process of soft-tissue adherence to begin. Connecting the drains to high-vacuum suction during the early postoperative period evacuates any fluid present and promotes soft-tissue adherence to the underlying abdominal wall ( Fig. 15.1 ). The drainage is expected to be significant initially and then to taper off within the first few hours. The drains can be connected to regular drainage bulbs at this time.

An abdominal binder placed at the completion of the procedure also facilitates fluid removal through the drains and promotes the compression of the fluid-filled soft tissue. The binder is an essential part of postoperative seroma management, as it maximizes the efficacy of the drain(s) and promotes adherence of the soft-tissue flap to the underlying abdominal wall fascia.

Re-evaluation of the position and tightness of the abdominal binder during the immediate perioperative period is very important. A binder that is too high or too loose will not compress the soft-tissue apron properly. On the other hand, a binder that is too tight or which applies uneven pressure endangers the blood supply and perfusion to the underlying flap. Careful inspection and discussion with caregivers regarding folds or creases in the binder, as well as the inadvertent presence of a drain tube between the binder and the abdomen, is very important.

Evaluating the capillary refill of the lower portion of the abdominal flap near the midline is a good way to assure that there is adequate soft-tissue perfusion and that the binder is not too tight ( Fig. 15.2 ). The binder should be maintained snug but not overly tight until the first postoperative visit, at which time soft-tissue perfusion and drainage are reassessed. The garment can then be worn more tightly during the subsequent days to further promote flap adherence. The drain(s) are removed when the drainage amount is less than 30–50 mL over a 24-hour period.

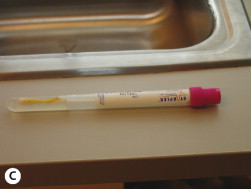

Should a seroma be detected following drain removal, percutaneous aspiration should be performed at least twice weekly until the accumulation ceases. During this time we recommend that the abdominal binder be worn continuously day and night. The lower central abdomen superior to the incision is usually a good place to aspirate a seroma because this area is frequently insensate and the fluid is most likely to pool here ( Fig. 15.3 ). A Betadine preparation will reduce the risk of introducing bacteria and producing a seroma infection. If the seroma fluid becomes turbid at any point, or there are any signs of infection, culture of the fluid should be considered ( Fig. 15.4 ).

Continuous drainage may be indicated for an unusually large or persistent seroma. A percutaneous catheter is placed using sterile technique in the office. It is secured to the skin via suture or tape and connected to an aspiration bulb. A Seromacath or a Jackson Pratt or comparable drain can be used. For seromas that remain recalcitrant despite drain replacement, the incision can be opened and a wick drain, such as a Penrose, can be placed to permit continuous drainage. This will allow the seroma pocket to close from the inside out and reduce the incidence of pseudo-bursa formation.

Hematoma ( Box 15.2 )

The large undermined area associated with abdominoplasty procedures, as well as the division of multiple perforators, is a good recipe for the creation of a hematoma. It is fortunate – and impressive – that the actual incidence of hematoma in abdominoplasty is quite low. It is a credit to the skill of plastic surgeons, the use of meticulous surgical technique, knowledge of the vascular anatomy of the abdominal soft tissue, and appropriate control of the transected perforators that an inherently ‘hematoma-prone’ procedure can be performed with little blood loss and with a very low incidence of hematoma.

- •

Despite the large surgical surface area and the release of many perforators, the incidence of hematoma following abdominoplasty is fairly low

- •

Patients with hematoma will often present within the first or second postoperative day

- •

Rapid swelling, discomfort, and ecchymosis are indicators of a hematoma

- •

The quality and quantity of the drain output may also support the diagnosis. The output can also be unremarkable, as the drains easily clog with clot

- •

Formal operative exploration and evacuation of the hematoma is the safest course of action. This will also expedite the healing process and offer the best aesthetic result

- •

Although any of the perforators can be a source of postoperative bleeding, we have found that the superficial inferior epigastric and the superficial circumflex vessels are the most frequent culprits

Most abdominoplasty patients presenting with hematoma do so within the first postoperative day ( Fig. 15.5 ). Any of the transected perforators can be the source of the hematoma, but most often the bleeding is from the superficial inferior epigastric or the superficial circumflex vessels. This is why we recommend ligutron or precise electrocautery of these vessels. The reason for this is twofold: first, the midline abdomen where the deep epigastric perforators are found is involved in myofascial plication. The process of myofascial plication invaginates this midline tissue and compresses the cauterized ends of the perforators from the deep epigastric arcade. Nearby perforators from the deep epigastric arcade that are not included in the plicated tissue are likely to be stretched by the plication process, potentially occluding them as well. Second, the source of the superficial inferior epigastric and superficial circumflex perforators maybe outside the boundary of the abdominal binder. The absence of the abdominal binder pressure makes these perforators more prone to postoperative bleeding if not properly controlled.

When hematomas do occur they are often clinically large enough to result in discomfort and contour irregularity. The course of action can be individualized, but it is best to return the patient to the operating room and evacuate the hematoma. Thorough removal of the hematoma fluid and irrigation of the abdominoplasty site should be performed ( Fig. 15.6 ). Occasionally the hematoma has solidified to the extent that a sizeable component of the incision needs to be opened in order to physically remove the clot.

Cellulitis ( Box 15.3 )

Cellulitis must be differentiated from skin hyperemia. Hyperemia is usually seen early during the first few postoperative days and is a normal physiologic reaction to the abdominoplasty procedure. Cellulitis, on the other hand, is unusual in the first few days after surgery: it is more commonly seen in the later part of the first or in the early part of the second postoperative week, usually after the drain(s) has been removed and the prophylactic antibiotics stopped.

- •

Cellulitis following abdominoplasty is most commonly seen by the end of the first postoperative week. Often, the drain(s) has been removed and the oral antibiotics have been stopped by this time

- •

Cellulitis is most frequently seen in the midline, just above the transverse incision

- •

This area is more likely to accumulate seroma fluid and is furthest from the vascular supply

- •

Initial management of simple cellulitis includes resumption of oral antibiotics, frequent follow-up evaluations, and attempts to aspirate any potential seroma fluid

Early cellulitis is often associated with increased skin temperature, erythema, localized discomfort, and increased edema of the skin and underlying soft tissue. The most common location for cellulitis is in the midline just above the transverse incision ( Fig. 15.7 ), which is the most prone to fluid accumulation and by design is the furthest away from the vascular supply of the abdominal soft-tissue apron. There may be no pain associated with the cellulitic area, as it is usually insensate. The initial management of early cellulitis is conservative and includes outlining the extent of the erythema, more frequent follow-up evaluations, and restarting or continuing standard oral antibiotics.