Lymphedema: Diagnosis and Treatment

Steven M. Levine

David W. Chang

Babak J. Mehrara

INTRODUCTION

Lymphedema is the accumulation of protein-rich interstitial fluid in tissues and occurs when the transport capacity of the lymphatic system is exceeded (Figure 97.1). Lymphedema can occur secondary to congenital abnormalities of the lymphatic system (primary lymphedema) or as a result of an acquired condition in which lymphatic channels are injured or obstructed (secondary lymphedema). In Western countries, lymphedema occurs most commonly as a complication of cancer treatment after lymph node excision with breast cancer patients making up the largest number of patients in the United States. As many as 50% of patients who undergo axillary lymph node dissection, and 4% to 7% of patients who undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy, will develop lymphedema.1 Lymphedema is also a common complication of the treatment of other malignancies. A recent meta-analysis of 7,790 patients reported a 16% risk of lymphedema in patients treated for a variety of tumors, including sarcoma (30%), melanoma (16%), gynecological (20%), and genitourinary (10%) malignancies.2 Overall, it is estimated that 3 to 5 million Americans suffer from lymphedema and as many as 25 to 50,000 new cases are diagnosed annually. Severe lymphedema is associated with recurrent infections, disfigurement, pain, secondary malignancies, and decreased quality of life, in addition to the financial burden on the health care system.

Development of effective treatment strategies for lymphedema has been hampered by the fact that the etiology of this disorder remains largely unknown. Although recent studies have delineated the molecular mechanisms that regulate lymphatic repair and regeneration, it is still not clear why lymphadenectomy or lymphatic injury results in lymphedema in some patients and not in others. Similarly, we cannot accurately predict the disease course for individual patients, their response to various treatment strategies, or the effectiveness of preventative options. As a result, treatment for lymphedema is palliative with a goal of preventing disease progression and symptomatic relief.

TYPES OF LYMPHEDEMA

Lymphedema that arises from a developmental abnormality of the lymphatic system is termed primary lymphedema. These disorders can be present at birth, or more commonly develop later in life manifesting as unilateral or bilateral limb edema. Congenital lymphedema is clinically evident at birth and accounts for 10% to 25% of all primary lymphedemas. As with most forms of primary lymphedema, females are affected twice as often as males and the lower extremity is involved three times more commonly than the upper extremity.

A subset of congenital lymphedema patients demonstrates a familial, sex-linked pattern of inheritance (termed Milroy’s disease) and accounts for approximately 2% of patients with congenital lymphedema. Milroy described this hereditary disorder in 1892 when he traced a single patient’s lymphedema through six generations. The disease is characterized histologically by hypoplastic lymphatic channels and variable degrees of dermal and collecting lymphatic agenesis. Recent studies have demonstrated that Milroy’s disease is caused by loss of function mutations in the vascular endothelial growth factor-3 receptor, a key regulator of lymphatic development and regeneration.

Lymphedema praecox is the most common form of primary lymphedema accounting for 65% to 80% of all cases. Patients with lymphedema praecox usually present with unilateral (70%) limb edema beginning after birth and before 35 years of age as a result of lymphatics that are reduced in caliber and number. Presentation at puberty is the most common age and females are affected four times as frequently as males.

Lymphedema tarda is a primary form of lymphedema that manifests clinically after the age of 35 years and accounts for a relatively small number of cases of primary lymphedema (10%). Lymphedema tarda most commonly affects the lower extremity and occurs more commonly in women. The diagnosis is made by exclusion of other forms of lymphedema or causes of limb swelling and often occurs with a familial pattern. Loss of function mutations of the FOXC2 gene have been reported in some patients, and histological examination usually demonstrates hyperplastic, tortuous lymphatics of increased caliber and number and incompetent or absent lymphatic valves.

SECONDARY LYMPHEDEMA

Secondary lymphedema is the acquired dysfunction of otherwise normal lymphatics. Traumatic lymphedema occurs as a consequence of scarring or injury following trauma, cancer treatment, burn injury, or radiation exposure and is the most common cause of lymphedema in the United States. Traumatic lymphedema can also occur after extensive skin resection performed for a variety of conditions including massive weight loss. Infectious lymphedema is caused by invasion of the lymphatic vessels with a foreign organism. This is usually the filarial worm, Wuchereria bancrofti, but can also be other microorganisms such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Treponema pallidum, or other organisms including streptococci and fungi. With between 140 and 250 million cases worldwide, filariasis remains the most common cause of lymphedema outside of the developed world. Inflammation resulting from invasion of the lymphatic system by microorganisms leads to progressive fibrosis and lymphatic dysfunction resulting in lymphedema of massive proportions.

Infiltration and obstruction of the lymphatic system with malignant cells can result in malignant lymphedema. This condition should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients who present with lymphedema without an obvious cause. Post-venous thrombosis lymphedema can occur after ligation or thrombosis of a major extremity vein and is thought to occur as a result of increased venous pressure diminishing lymphatic return.

DIAGNOSIS OF LYMPHEDEMA

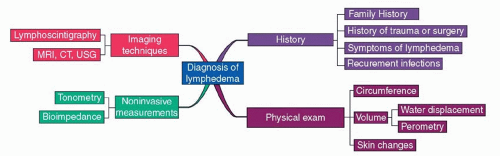

The diagnosis of lymphedema is usually made by clinical history and physical examination (Figure 97.2).3 Patients typically present with complaints of limb swelling; tightness in the skin; functional complaints such as heaviness, fatigue, and difficulty moving a joint; and a history of recurrent infections. Limb circumference or volume measurements can be performed to confirm limb swelling. A difference in limb measurement of greater than 2 cm or a 200 ml increase in volume when compared with the unaffected limb is generally considered clinically significant lymphedema. Most patients will also have a history of traumatic injury to the lymphatic system since secondary lymphedema is the most common form of lymphedema in the United States. Obesity, infections, and a history of radiation therapy increase the risk of lymphedema significantly after surgery. Patients with primary lymphedema may have a family history; however, sporadic forms of primary lymphedema also occur. In these situations, the diagnosis of primary lymphedema is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Rarely, patients with long-standing lymphedema will present with lymphangiosarcoma, an aggressive tumor with a 5-year survival of less than 10% (Figure 97.3). This complication was first reported by Stuart and Treves in 1948 in patients with postmastectomy lymphedema and is also referred to as Stuart-Treves syndrome. Patients present with red or purple nodules in the diseased tissues and are most commonly treated with amputation. Despite aggressive surgical management, however, the average survival after diagnosis is only 19 months.

FIGURE 97.2. Diagnosis of lymphedema. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography; USG, ultrasonography. |

The differential diagnosis of lymphedema includes deep vein thrombosis, congestive heart failure, malignancy, and infection. In some cases, additional tests may be required to diagnose lymphedema. Lymphoscintigraphy is performed by the injection of radiolabeled colloid into the region of interest and then its transport is followed using a gamma counter. Although lymphoscintigraphy is helpful in the diagnosis of lymphedema, the interpretation of these studies is not standardized making it difficult to compare findings between studies. The use of the lymphatic transport index has been suggested to standardize these findings but has not been widely accepted. Lymphoscintigraphy is differentiated from contrast lymphography, which involves the injection of radio-opaque dye directly into peripheral lymph vessels with radiological assessment of lymphatic flow. This test has largely been abandoned, however, due to technical difficulties and also because the contrast dye can injure the remaining lymphatic vessels resulting in worsening of lymphedema.

Lymphedema diagnosis and quantification can also be performed with a variety of noninvasive methods, including perometry, tissue tonometry, bioimpedance spectroscopy, and radiologic imaging techniques. Perometry is a method to calculate limb volumes and relies on the use of infrared scanning technology to estimate limb cross-sectional diameters at multiple intervals. Bioimpedance measures the rate of electrical current transmission through tissues and can estimate fluid content in a lymphedematous limb when compared with the normal limb. This technique is particularly helpful in early stage lymphedema. Finally, both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computerized axial tomography (CT) can be used to assess lymphedema. On both MRI and CT scan, lymphedema appears as a subcutaneous honeycomb pattern. Finally, ultrasound can be used to evaluate lymphedema by correlating the thickness of the subcutaneous tissue with the progression of lymphedema and fibrosis.

STAGING OF LYMPHEDEMA

Lymphedema can be classified based on its clinical features, changes in limb volumes, or changes in limb circumference. Several classification schemes exist, though no single system has gained universal acceptance. The International Society of Lymphology stages lymphedema based on changes in the tissues.4 Stage 0 (latent lymphedema) is defined as impaired fluid transport without evidence of swelling or edema. Stage I is the early accumulation of protein-rich interstitial fluid, resulting in measurable swelling with pitting of the skin that decreases after compression garment treatment. Stage II is characterized by limb swelling (non-pitting) that does not decrease with

compression due to fibrofatty tissue deposition. Stage III (lymphostatic elephantiasis) demonstrates severe swelling, fibrosis, adiposity, and skin changes (hyperkeratosis and acanthosis). Campisi et al. have proposed a similar staging scheme with stage I defined as initial or irregular edema, stage II as persistent lymphedema, stage III as persistent lymphedema with lymphangitis, stage IV as fibrolymphedema (“column” limb); and stage V as elephantiasis.5

compression due to fibrofatty tissue deposition. Stage III (lymphostatic elephantiasis) demonstrates severe swelling, fibrosis, adiposity, and skin changes (hyperkeratosis and acanthosis). Campisi et al. have proposed a similar staging scheme with stage I defined as initial or irregular edema, stage II as persistent lymphedema, stage III as persistent lymphedema with lymphangitis, stage IV as fibrolymphedema (“column” limb); and stage V as elephantiasis.5

FIGURE 97.3. Patient with lymphangiosarcoma of the right arm after long-standing lymphedema secondary to mastectomy and axillary lymph node dissection. |

Lymphedema can also be classified based on changes in limb circumference when compared with preoperative measures or in comparison to the unaffected limb. Increases of less than 2 cm are considered mild lymphedema, 2 to 4 cm moderate lymphedema, and greater than 4 cm severe lymphedema. Though easy to conceptualize, this classification system has two major flaws: the inter-examiner variability of measurements and the relative nature of the grading scheme (i.e., a 2 cm increase in a thin patient is more noticeable than a 2 cm increase in an obese patient). Furthermore, circumference measurements may vary significantly due to the use of compression garments or changes in patient activity.

NONSURGICAL TREATMENT OF LYMPHEDEMA

Complex Decongestive Therapy

Complex decongestive therapy (CDT) is the mainstay of lymphedema management and aims to decrease the amount of fluid in lymphedematous tissues.6,7 CDT is comprised of multiple therapies and is usually divided into two phases. Phase 1 is an intensive treatment regimen typically performed once or twice daily for 4 to 6 weeks. Patients are treated with manual lymphatic drainage (MLD), skin care, compression wraps with short-stretch bandages, and light exercises. MLD is a form of soft tissue massage performed with light strokes in a directional manner to increase lymphatic fluid flow away from damaged lymphatics. In phase 2, MLD use is decreased and patients are primarily treated with compressive garments and skin care administered indefinitely since lymphedema is a chronic disease. Some patients are given additional phase 1 treatments if there is evidence of relapse or progression of disease. In addition, some centers prescribe intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) in this phase.

CDT is effective in most patients; however, this therapy is time intensive, is expensive, and requires a high level of sophistication on the part of the patient and caregiver. Certified lymphedema therapists are sometimes difficult to find, and the costs of long-term care are not always covered by health insurance policies. These difficulties contribute to relatively high rates of patient noncompliance.

Compression Therapy

Compression therapy includes a wide range of treatments, including multilayer bandaging, self-adherent wraps, and custom-made pressure garments. The goal of these treatments is to restore hydrostatic pressure in the limb and improve lymph flow. It is important to note that wraps are performed with low-stretch bandages rather than high-stretch bandages (e.g., Ace bandage). This difference is important since short-stretch bandages maintain a constant pressure at rest but exert an increased pressure with exercise. In contrast, high-stretch bandages may exert high pressures at rest thereby causing circulatory compromise.

Intermittent Pneumatic Compression

The IPC device is a pneumatic cuff connected to a pump that simulates the natural pump effect of muscular contraction on the peripheral lymphatic system. IPC pumps typically cycle and have pressures in the range of 35 to 180 mm Hg applied either uniformly or sequentially. Although some studies have shown that IPC can be effective in patients with secondary lymphedema, particularly when combined with compression garments, there is currently no consensus on the use of these devices and costs of these devices are usually not covered by insurance plans.

Exercise

For many years, it was thought that patients with lymphedema or those at risk for developing lymphedema should refrain from vigorous exercise with the affected limb. This concept was based on the idea that exercise increased blood flow and hence lymphatic load. More recently, however, multiple prospective studies have demonstrated significant benefits in monitored exercise regimens. Although the exact mechanisms by which exercise improves lymphedema remain unknown, it is thought that activation of the muscular pump mechanism helps propel lymphatic fluid in the affected extremity. It is also possible that exercise improves lymphedema by promoting weight loss and maintenance of ideal body weight since these factors have also been shown to decrease the incidence and severity of lymphedema.

SURGICAL TREATMENT OF LYMPHEDEMA

Although the mainstay of lymphedema treatment is nonsurgical, a number of surgical options have been described. However, there is currently no consensus on patient selection, the type of procedure, timing of intervention, or postoperative management. In most cases, surgery is reserved for patients with significant symptoms and functional complaints who have failed conservative management. Some authors, however, describe their experience with patients who are simply dissatisfied with compression garments.

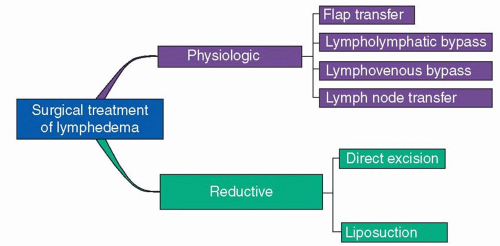

The surgical options available for lymphedema can be broadly divided into physiologic approaches and reductive techniques (Figure 97.4). Physiological treatments aim to restore lymphatic flow and include flap transposition, lymph node transfers, and lymphatic bypass procedures. Reductive

techniques, such as surgical excision or liposuction, simply aim to treat the consequences of sustained lymphatic fluid stasis by removing the fibrofatty tissues that has been pathologically generated.

techniques, such as surgical excision or liposuction, simply aim to treat the consequences of sustained lymphatic fluid stasis by removing the fibrofatty tissues that has been pathologically generated.

PHYSIOLOGICAL METHODS

Flap Transfer

The first reported case of flap transposition for the treatment of lymphedema is credited to Gilles who described a two-stage tubed flap transfer from the arm to the abdomen and ultimately the affected groin. He reported improvement in the patients’ chronic lymphedema and hypothesized that the skin flap provided a path for lymphatic fluid to bypass the damaged inguinal region. Goldsmith used this same concept and reported his experience with the use of pedicled omentum flap transpositions in a series of 22 patients (13 with lower extremity and 9 with upper extremity). Nearly half of the patients experienced good results; however, due to the high rates of complications, including adhesions, abdominal wall hernias with incarcerated bowel, pulmonary embolus, and wound healing complications, the procedure failed to gain widespread acceptance. With the advent of modern pedicled and free flap procedures, several case series and case reports have been published detailing improvements in lymphedema of the lower/upper extremity, genitalia, and head and neck after flap transfer. Unfortunately, the unpredictable outcomes associated with these procedures have precluded their widespread clinical application.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree