Lower Facial Rejuvenation

Samuel M. Lam

Edwin F. Williams III

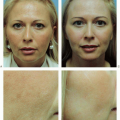

The rhytidectomy, or facelift, procedure has remained synonymous with facial rejuvenation in the lay public’s mind. The term “facelift” entered the lexicon to signify any reparative endeavor (“The dilapidated edifice underwent a much-needed facelift”). In the past, a cervico-facial rhytidectomy represented the principal, if not sole, method by which the facial plastic surgeon could achieve global restoration for the aging face. The midface was uncharted terrain; and traditional options for brow rejuvenation often were judged too invasive to merit routine implementation. For these reasons, the facelift was (and often still is) undertaken to lift the midface and temporal brow region in an effort to provide a complete full facial rejuvenation through one procedure. This ambitious surgical enterprise may not always bear the best aesthetic result because of unnatural vectors of suspension and violation of the temporal hair tuft, a stigma of aging and surgical manipulation. Furthermore, the overly pulled (so-called “windswept” look) of a poorly executed facelift has traumatized the public psyche and dispirited many prospective patients from venturing any further into the realm of cosmetic surgery.

Another obstacle that has potentially hampered public enthusiasm concerns the confusing array of facelift types that are advocated, including the tri-plane facelift, the deep-plane facelift, the composite facelift, the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) lift, the subperiosteal lift, the endoscopic facelift, the S-lift, the vertical facelift, the “weekend” facelift, the “lunch-time” facelift, and so on in endless thematic permutations. Clearly, some of these surgical techniques reflect ensconced ideologies based on empiricism and scientific inquiry, whereas others testify to unrepentant marketing strategies. Unfortunately, the public is often at the mercy of the Internet and other prejudicial mass media resources and unable to distinguish between sham and untrammeled science.

This chapter does not purport to offer a wholly impartial perspective on lower facial rejuvenation but rather espouses a philosophy and strategy that have emerged from significant clinical experience. Although deeper-tissue (sub-SMAS, extended sub-SMAS, deep-plane, and composite) rhytidectomy procedures have their proponents, the authors have noted a trend toward more conservative restorative modalities in the United States.1 The protracted healing time and potential for higher morbidity may not always translate into a notable clinical improvement; an opinion that has been borne out by the authors’ clinical experience.2,3 Further, the authors contend that this return to a more conservative operative technique represents a paradigm shift that matches the present minimal-invasive Zeitgeist. Nevertheless, this controversy undoubtedly will be sustained for quite some time as advocates of deep-plane and SMAS techniques continue to debate the issue.

This chapter offers the reader a systematic appraisal of the aging lower face and a host of therapeutic options. For instance, the younger patient who presents with exclusive submental adipose accumulation without notable platysmal diastasis requires only a localized liposuction or lipectomy. These diagnostic deliberations are explored in more depth in the section on preoperative considerations. The reader is reminded that not all techniques for lower facial rejuvenation are reviewed in this chapter (e.g., collagen injection and alloplast implantation, for which a chapter dedicated to adjunctive procedures has been allocated). These less invasive procedures may be used in conjunction with or independent of the procedures described in this chapter in a strategy for global facial rejuvenation. Accordingly, these adjunctive procedures are reviewed in the section on preoperative considerations so that the surgeon can determine when and how these procedures can be implemented or combined. However, operative detail may be found in Chapter 8. Thoughtful reflection and open dialog will ensure that the surgeon and patient arrive at the optimal tactical treatment plan.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS: PATIENT SELECTION AND RELEVANT ANATOMY

As stressed in the preceding and elsewhere, the surgeon must venture to grasp the aesthetic flaw that concerns the patient before the surgeon proffers his or her own independent management agenda. After the patient has declared the specific locus or loci of concern, the surgeon must determine whether the patient desires a more limited, targeted approach (adjunctive procedures such as collagen, botulinum toxin, etc.) or a more extensive rejuvenative protocol (e.g., submentoplasty, chin augmentation, rhytidectomy, etc.). However, patients often look toward the surgeon for his or her informed and educated opinion, and the surgeon should help

organize for the patient the procedures that will offer the most return on investment. For example, the surgeon can proclaim, “If you could only do one thing, this would give you the most bang for your buck (pardon the colloquialism); and two things I recommend, etc.” Obviously, the surgeon should recommend only those procedures that are in alignment with the patient’s declared interest; that is, the surgeon should not dwell on a perceived correctable nasal flaw if the patient presents for neck rejuvenation. The reader is advised to review the section on the dynamics of an effective consultation in Chapter 3 for more cogent remarks. The remainder of this section outlines a systematic approach the surgeon can apply when contemplating the optimal treatment strategy for the patient. The two principal areas that are discussed are the lower face (dependent jowl as well as prominent labiomandibular and nasolabial folds) and the neck region (platysmal banding, excessive submental adipose, redundant skin, and underprojected chin). Because these two regions are confluent and overlap, certain topics are covered in both sections by necessity. In addition, the revision or “tuck-up” rhytidectomy patient deserves special consideration during the preoperative evaluation. Although the lip constitutes part of the lower face, this particular specialized anatomic region is thoroughly investigated in Chapters 8 and 9 and is not repeated here.

organize for the patient the procedures that will offer the most return on investment. For example, the surgeon can proclaim, “If you could only do one thing, this would give you the most bang for your buck (pardon the colloquialism); and two things I recommend, etc.” Obviously, the surgeon should recommend only those procedures that are in alignment with the patient’s declared interest; that is, the surgeon should not dwell on a perceived correctable nasal flaw if the patient presents for neck rejuvenation. The reader is advised to review the section on the dynamics of an effective consultation in Chapter 3 for more cogent remarks. The remainder of this section outlines a systematic approach the surgeon can apply when contemplating the optimal treatment strategy for the patient. The two principal areas that are discussed are the lower face (dependent jowl as well as prominent labiomandibular and nasolabial folds) and the neck region (platysmal banding, excessive submental adipose, redundant skin, and underprojected chin). Because these two regions are confluent and overlap, certain topics are covered in both sections by necessity. In addition, the revision or “tuck-up” rhytidectomy patient deserves special consideration during the preoperative evaluation. Although the lip constitutes part of the lower face, this particular specialized anatomic region is thoroughly investigated in Chapters 8 and 9 and is not repeated here.

The Neck and Chin Region

The central neck region is the area of principal concern for most patients. In this area, platysmal banding, submental adipose, and redundant skin can be readily apparent. A hypoplastic mentum can exacerbate these conditions and make surgical intervention less successful. As mentioned, submental adipose tissue may be an unsightly feature that appears even in early age, particularly in the White race. Submental fullness is usually more a problem only in the mature Asian patient. Conversely, platysmal diastasis is twice as prevalent in the White than the Asian race (60% versus 30%).4 Nevertheless, individual variations mandate that the surgeon tailor the specific surgical plan according to each patient’s anatomy.

The younger patient (in the thirties) often presents with submental fullness caused by adipose accumulation at times disproportionately greater than the corporal distribution (e.g., thighs and abdomen). Fortunately, a full rhytidectomy is a premature and unwarranted procedure, because redundant skin and platysmal definition have yet to occur. In addition, the favorable fibrosis induced by cervical dissection permits contraction of the overlying skin sleeve, which is still relatively elastic in the younger patient. An augmentation mentoplasty may enhance the surgical outcome by better defining the cervico-mental angle. A profile view taken in the correct Frankfort horizontal plane with appropriate preoperative and postoperative digital manipulation often is a helpful adjunct in convincing the patient of the projected improvement. Satisfaction among younger patients with confined submental adipose tissue who have undergone targeted liposuction has been uniformly high.

Augmentation mentoplasty is a marvelous adjunct to lower facial rejuvenation for several reasons. First because mentioned, when combined with submental liposuction, cervico-mental definition is increased. Second, an extended alloplast that traverses the prejowl region can diminish a heavy jowl appearance, especially when combined with a rhytidectomy. Accordingly, success of a rhytidectomy is partly contingent on the presence of a bony, angular face: The more projected mentum serves as a focal point over which the SMAS may be suspended and the skin redraped. Third, some bony resorption of the mentum occurs as a patient matures, which contributes in part to the loss of structural support and consequent platysmal separation. Alloplastic augmentation restores the more youthful prominence of the chin. Fortunately, added dissection time is minimized when combined with a submental liposuction or platysmal approximation because the same incision is used for all the preceding procedures. A sliding-type osseous genioplasty is a viable alternative for augmentation mentoplasty and is particularly versatile in that the chin may be augmented, reduced, vertically shortened, or laterally repositioned.5 However, the authors have less extensive experience with this technique and do not elaborate on the technical specificities entailed with this procedure.

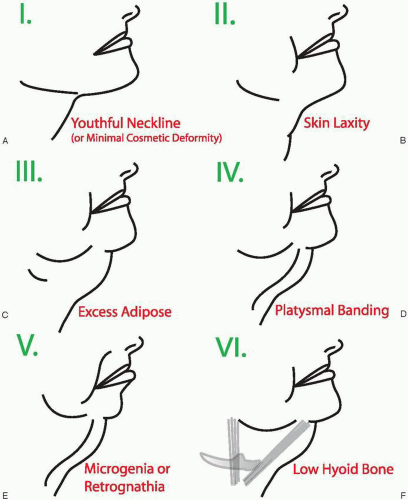

Dedo’s renowned thesis on neck classification is worthy of review, because distinctive anatomic configurations and dispositions dictate surgical intervention and potentially limit surgical success—a fact that must be conveyed to the patient during the preoperative phase (Fig. 5-1).6 A class I deformity exhibits only minimal cosmetic deficiency that may or may not warrant surgical intervention. A class II deformity presents with only skin laxity. This condition is usually quite rare because concomitant submental fat accumulation and platysmal diastasis are usually present to a varying extent. Submental liposuction alone may induce sufficient favorable skin contraction if minimal skin laxity is present. Alternatively, a limited rhytidectomy incision that only extends under the ear lobule in a lazy S configuration may provide enough exposure for dissection and adequate skin excision. However, cervical skin redundancy usually requires the standard postauricular incision for proper adjustment (vide infra). A class III deformity refers to excessive submandibular and submental adipose, surgical correction of which has been described above. A class IV deformity refers to anterior banding of the platysma, which is addressed in the following paragraph. Class V deformity describes the condition of retrognathia or microgenia* that can be improved with alloplastic

implantation, as outlined in the preceding. Finally, a class VI deformity describes a low-residing hyoid bone that can interfere with optimal cervical rejuvenation. Ideally, the hyoid should be situated at the fourth vertebra, near the cervical-mental interface. Although not included in the original classification schema, a ptotic submandibular gland should be carefully observed in the preoperative evaluation because this condition may limit improvement with a rhytidectomy; further correction should not be indicated for an aesthetic objective alone.

implantation, as outlined in the preceding. Finally, a class VI deformity describes a low-residing hyoid bone that can interfere with optimal cervical rejuvenation. Ideally, the hyoid should be situated at the fourth vertebra, near the cervical-mental interface. Although not included in the original classification schema, a ptotic submandibular gland should be carefully observed in the preoperative evaluation because this condition may limit improvement with a rhytidectomy; further correction should not be indicated for an aesthetic objective alone.

The anterior platysmal border becomes more accentuated over time because of loss of skeletal support and atrophy of the muscle. The anterior platysmal fibers insert into the mandibular periosteum and demonstrate the greatest variability in distribution. Posteriorly, the muscle fibers blend with the risorius muscle and the SMAS. Therefore, the combination

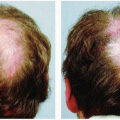

of suturing the anterior platysmal bands with suspension of the posterior platysma and SMAS affects a hammocklike sling that restores definition to the neck. At times, men seek the most expedient remedy for anterior platysmal banding while refusing a rhytidectomy at all costs because of societal stigma and desire for limited surgery. Jowling and lower facial descent are of secondary concern to many men. If the male patient cannot be convinced that a rhytidectomy is the preferred route, the alternative of direct skin excision, open lipectomy, and platysma suturing can be entertained.7 The major drawback, of course, with this approach is a noticeable incision in the midline of the neck, which can be camouflaged with multiple cutaneous z-plasties or geometric broken-line repair. The former type of repair is favored because of the alacrity of this closure and minimization of scar contracture. If the patient understands this potential (but low) risk, then a direct excision can be undertaken.

of suturing the anterior platysmal bands with suspension of the posterior platysma and SMAS affects a hammocklike sling that restores definition to the neck. At times, men seek the most expedient remedy for anterior platysmal banding while refusing a rhytidectomy at all costs because of societal stigma and desire for limited surgery. Jowling and lower facial descent are of secondary concern to many men. If the male patient cannot be convinced that a rhytidectomy is the preferred route, the alternative of direct skin excision, open lipectomy, and platysma suturing can be entertained.7 The major drawback, of course, with this approach is a noticeable incision in the midline of the neck, which can be camouflaged with multiple cutaneous z-plasties or geometric broken-line repair. The former type of repair is favored because of the alacrity of this closure and minimization of scar contracture. If the patient understands this potential (but low) risk, then a direct excision can be undertaken.

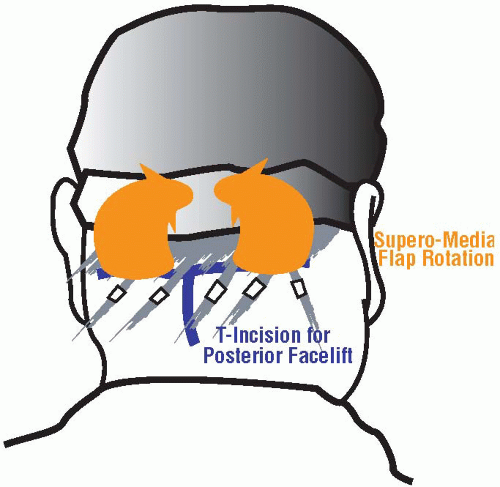

Skin redundancy of the neck can be effectively eliminated by a standard rhytidectomy in most cases. The described technique of direct excision is an alternative method in the select patient. The severity of cervical skin excess may mandate an adjunctive posterior neck lift in rare circumstances.8 This procedure employs a T-shaped incision in which the horizontal limb resides just within the hair-bearing area near the hair-hairless interface and in which the vertical limb falls principally in the non-hair bearing area (Fig. 5-2). Therefore, the patient must be aware that a vertical scar in the occipital midline may be evident postoperatively. Dissection is carried in the subcutaneous, supramuscular plane until adequate elevation permits sufficient skin redraping. Often, dissection must be carried out near the cervical rhytids to achieve enough skin mobility for complete effacement of the rhytidosis. Redundant skin is excised and the wound edges approximated to each other and tacked to the underlying occipital musculature. A posterior neck lift should be undertaken at a minimum of several months after initial rhytidectomy in order to determine accurately whether this procedure is needed and how much skin excision is required, as well as to minimize the risk of flap necrosis. It should be emphasized again that this procedure is only rarely indicated. Of note, any skin resurfacing in the neck region should be undertaken with great caution because the pilosebaceous density is markedly attenuated compared with that of the face (see Chapter 9). Clearly, cervical flap elevation should delay any resurfacing for a minimum of 6 months, at which time resurfacing should be carried out with even greater conservatism.

The Lower Facial Region

The component regions of the lower face embrace the jowl, which continues upward as the labiomandibular fold (or marionette line), and the nasolabial fold (or smile line). The lower face can be only partly (and somewhat arbitrarily) delineated from the neck region, but is done so herein in order to provide a rational framework for the reader’s preoperative assessment. Although the jowl may be conceived of as an extension of the labiomandibular fold, this structure represents a unique surgical entity. Unlike the upper aspect of the labiomandibular fold that requires a soft-tissue filler, the jowl region can be effectively effaced only with a cervico-facial rhytidectomy. In fact, if the patient is principally concerned with the labiomandibular and nasolabial depressions, then he or she should be dissuaded from rhytidectomy. Instead, soft-tissue augmentation may provide the best solution to address the patient’s concerns.

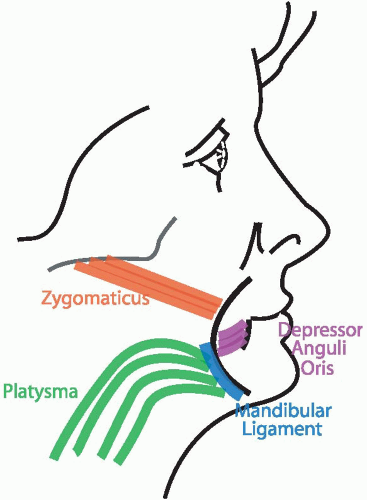

The labiomandibular fold is defined superiorly by the cutaneous insertion of the depressor anguli oris muscle. At rest, the labiomandibular fold is only visible along the upper one third to one half of its distance by virtue of the action of the depressor anguli oris muscle on the overlying skin. The fold is tethered specifically at two points: the aforementioned depressor muscle superiorly and the mandibular ligament along its entire length (Fig. 5-3).9 During animation, the zygomaticus and platysma muscles exert their pull at these two points of fixation, thereby causing a bowstring effect and forming a continuous fold. These unique properties of the labiomandibular fold inform the most suitable course of labiomandibular effacement. Because the inferior aspect of the crease is absent at rest, the surgeon is advised to concentrate his or her efforts at soft-tissue augmentation only along the superior aspect of the fold. Soft-tissue injectables (temporary)

or solid implants (permanent) are both acceptable methods of augmenting the superior labiomandibular fold. For a more detailed description of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative management of the nasolabial and labiomandibular folds, the reader is directed to Chapter 8. As mentioned, the inferior portion of the labiomandibular fold that is accentuated by the jowl should be addressed with a rhytidectomy rather than augmentation materials.

or solid implants (permanent) are both acceptable methods of augmenting the superior labiomandibular fold. For a more detailed description of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative management of the nasolabial and labiomandibular folds, the reader is directed to Chapter 8. As mentioned, the inferior portion of the labiomandibular fold that is accentuated by the jowl should be addressed with a rhytidectomy rather than augmentation materials.

The nasolabial fold is defined by the cutaneous insertion of four principal muscles: the two levator muscles (anguli oris and alaeque nasi) as well as the paired zygomaticus muscles (major and minor).** Unlike the labiomandibular fold, the nasolabial fold may be apparent along its entire length at rest and during animation. The nasolabial fold may be thought of as a lateral mountain and a medial valley, the latter of which should be elevated with augmentation materials to soften the transition between the two areas. Some authors have also advocated direct, transcutaneous microliposuction of the lateral raised aspect to soften the transition further. However, liposuction in this area may be less forgiving than in the cervical region. If a concomitant rhytidectomy is planned, the SMAS may be excised before imbrication and used as soft-tissue filler. Unfortunately, the nasolabial and labiomandibular folds are recalcitrant to effacement via traditional rhytidectomy, regardless of whether a deep-plane or SMAS technique is undertaken.2

The Revision Rhytidectomy Patient

When a patient inquires in the preoperative period whether a facelift will endure for perpetuity, the surgeon can respond affirmatively. The surgical result will persist; however, the patient will continue to be subjected to both extrinsic (smoking, diet, exercise, stress, sun exposure, etc.) and intrinsic (continued aging and a genetic predisposition toward aging) forces that will slowly erode the once-stellar outcome. An example often illuminates the situation in a more concrete fashion for the patient: If the patient had a twin sibling, the patient would always appear younger than his or her twin if all extrinsic factors were negated. Based on multiple variables, the patient may return as soon as 3 years after the initial surgery for a tuck-up procedure or even a decade or more later. It may be worthwhile to introduce to the patient that a tuck-up facelift may be needed at some later interval, even as short as 2 years, so that the patient will be more accepting of this need when the time comes.

What constitutes the difference between a tuck-up and a revision facelift? A tuck-up procedure is one in which the surgeon is revisiting his or her own work, and revision surgery entails that the surgeon is operating on his or her colleague’s previous surgery. Although this distinction is meant to be facetious to a certain extent, it accurately encapsulates a notable truism. When a surgeon must reoperate on another surgeon’s facelift, he or she encounters a potential host of problems. First and foremost, the type of incisions that the other surgeon elected to undertake often does not parallel one’s own choices. Therefore, when very little redundant skin is already present (a fact that is discussed in greater detail in the intraoperative section), the surgeon must make deliberate choices as to where he or she should create the new incisions. These incisions, which are often less than ideal in terms of exuberant scarring and location, mandate excision of the existing incision and relocation (if possible) to a more favorable site. In addition, if the facelift result is suboptimal, the surgeon must aim to correct his or her colleague’s work. All of these factors often make “revision” surgery more arduous than a “tuck-up” of one’s own work. Furthermore, this semantic distinction offers the surgeon a favorable language in which to couch the new surgical enterprise.

At times, a secondary rhytidectomy may prove difficult for another reason: The patient may have unrealistic expectations of the rejuvenative potential because the degree of improvement may be more limited than in the primary setting. In the rare circumstance in which the patient demands further neck tightening than the surgeon can realistically achieve with a conventional tuck-up procedure, a rhytidectomy with an expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) or Gore-Tex (W.L. Gore and Associates, Inc., Flagstaff, AZ) sling may be indicated. However, the authors tend to be reluctant to use alloplasts on a frequent basis for the attendant problems that may arise with foreign materials. In addition, the patient should be counseled that the implant may be palpable and require adjustment if it feels too constrictive. The ePTFE sling should be offered as a surgical option only to the most fastidious patient who already has an established rapport with the surgeon. Therefore, the ePTFE sling should almost never be performed in the primary setting according to the senior author’s experience. It should be reiterated that only a very select patient qualifies for placement of an ePTFE sling.

Psychological Aspects of the Facelift Patient

Apart from the anatomic considerations already elaborated, the surgeon always should be mindful of the psychological dynamics that inform the patient’s motivation for facelift surgery.10 Edgerton classified four subtypes of patients who seek facial rejuvenation by age and sex.11,12 The first three categories refer to women; the fourth category is reserved for men. The first category concerns the woman aged 29 to 39 who desires surgical rejuvenation: She is viewed as an emotionally dependent personality who seeks constant approbation from her spouse and may not have fully transitioned from adolescence to adulthood in terms of psychological maturity. Given the little adjunctive procedures (e.g., collagen, botulinum toxin, chemical peels, etc.) that are available today, this categorization may be a bit outdated. The second category is defined by the woman aged 40 to 50 (“the worker group”) who desires to maintain her productivity in the workplace and wishes a countenance to match her energetic lifestyle. Often, these patients only seek one to two procedures that can improve their look. The third category refers to the woman over 50 years old (“the grief group”) who has lost support from her spouse either through divorce or death and is looking for a major lifestyle change through cosmetic surgery. These patients tend to pursue plastic surgical intervention with sustained fervor, demanding additional procedures but infrequently being fully satisfied with the outcome. The final, and fourth, group describes the male facelift patient and is further subdivided into two types. One subcategory refers to the male patient over 50 who is secure in his occupation and is happily married but desires to remain competitive at work: He believes that a facelift may offer him a competitive advantage in a work environment increasingly populated by younger faces. The second type of male facelift patient is the man who is recently widowed or divorced and maintains a relationship with a much younger partner: He desperately wants to retain approbation from his more junior companion and believes that a facelift may narrow the age difference. Clearly, these broad categories are not universally applicable to all patients but are only intended to serve as a framework by which the surgeon may evaluate the prospective rhytidectomy patient in a systematic fashion.

INTRAOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS: TECHNIQUE AND SALIENT TECHNICAL POINTS

Submentoplasty with Liposuction

A submentoplasty may be effectively combined with a rhytidectomy or chin augmentation for the optimal aesthetic result. It consists of two principal components: submental liposuction and anterior platysmaplasty. The former may be all that is required for a younger patient, whereas both elements may be necessary for the more mature patient as part of a rhytidectomy. The submentoplasty is always performed at the outset before a rhytidectomy, because the approximated anterior border of the platysma is difficult to unite after the lateral pull of the rhytidectomy has been completed. Similarly, submental liposuction always precedes anterior platysmaplasty because the removal of adipose and concomitant undermining permit visualization of the skeletonized platysma. Chin augmentation should always follow a submentoplasty but precede a facelift because the submentoplasty incision is used as the point of entry for chin implantation. Further, vigorous submentoplasty may disturb the position of the implant if performed after implant insertion.

Submentoplasty should be considered practically part of a complete rhytidectomy but is discussed herein as a separate procedure for the sake of clarity and to emphasize the versatility of it as an independent procedure (Fig. 5-4). Submental dissection should precede a rhytidectomy in most circumstances, even in the leanest necks that may not otherwise appear by intuition to warrant this intervention. Uniform submental or submandibular flap undermining promotes favorable skin contraction that largely enhances a rhytidectomy result. Undoubtedly, aggressive liposuction should be avoided in a very thin neck for risk of producing an overskeletonized appearance. Instead, sharp scissor dissection only (i.e., undermining alone) may be sufficient in these circumstances. Similarly, a platysmaplasty is justified in most cases when a rhytidectomy is also planned because the combined effect can be beneficial for the neck contour. However, if a patient presents with only minimal jowl formation correctable with an S-lift, or short-incision, rhytidectomy, then a submentoplasty of any kind may not be a requisite step.

The submentoplasty begins with a straight incision about 1 mm posterior to the submental crease that extends typically

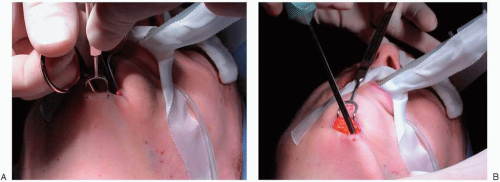

about 2 cm in breadth. The incision always should fall slightly posterior to the submental crease because placement of the incision directly in the crease will deepen over time so that the line will become lamentably conspicuous. After the initial incision through the skin to the underlying subcutaneous adipose is accomplished, wide double-hooked retractors are placed into the superior and inferior aspects of the wound for proper tension and retraction: The assistant retracts the superior flap while the surgeon retracts the inferior flap. The surgeon then performs wide undermining of the flap from just inferior to the jaw line (1 to 2 cm below) across the submental region to the contralateral jaw line using a pair of Metzenbaum scissors in the subcutaneous plane (Fig. 5-5A). Dissection should not pass directly over the jaw line in order to minimize risk of marginal mandibular nerve injury. Although the nerve should be protected under the platysma in most cases, an attenuated or dehiscent platysmal layer may predispose the nerve to inadvertent harm. Furthermore, dissection with a pair of Metzenbaum scissors is preferred to blunt tunneling dissection with the liposuction cannula because the former permits a more uniform undermining and thereby reduces the chance of uneven contour to the skin. The depth of dissection should leave approximately a 3- to 4-mm thick skin subcutaneous flap so as to avoid an uneven contour that may develop after liposuctioning and ensure vascularity to the overlying skin flap.

about 2 cm in breadth. The incision always should fall slightly posterior to the submental crease because placement of the incision directly in the crease will deepen over time so that the line will become lamentably conspicuous. After the initial incision through the skin to the underlying subcutaneous adipose is accomplished, wide double-hooked retractors are placed into the superior and inferior aspects of the wound for proper tension and retraction: The assistant retracts the superior flap while the surgeon retracts the inferior flap. The surgeon then performs wide undermining of the flap from just inferior to the jaw line (1 to 2 cm below) across the submental region to the contralateral jaw line using a pair of Metzenbaum scissors in the subcutaneous plane (Fig. 5-5A). Dissection should not pass directly over the jaw line in order to minimize risk of marginal mandibular nerve injury. Although the nerve should be protected under the platysma in most cases, an attenuated or dehiscent platysmal layer may predispose the nerve to inadvertent harm. Furthermore, dissection with a pair of Metzenbaum scissors is preferred to blunt tunneling dissection with the liposuction cannula because the former permits a more uniform undermining and thereby reduces the chance of uneven contour to the skin. The depth of dissection should leave approximately a 3- to 4-mm thick skin subcutaneous flap so as to avoid an uneven contour that may develop after liposuctioning and ensure vascularity to the overlying skin flap.

Instrumentation and Equipment for Submentoplasty and Rhytidectomy

Prep Stand:

Nonsterile gloves

10-cc syringe (2), 27-gauge (11/4-inch long) needle (2) with lidocaine 1% and 1:100,000 epinephrine

Surgical marking pen

Instruments:

Basic soft-tissue instrument set (Chapter 4)

Bovie hand piece and tip

Sutures:

2-0 Silk FS (C-15, CE-6) [C8] <ED-3> needle (to retract the ear)

CV-3 Gore-Tex† Th-26 needle (for SMAS suspension) 5-0 chromic P-3 (P-13, PRE-2) <RE-3> needle (2) (for postauricular skin closure)

6-0 polypropylene P-3 (PRE-2, P-13) <RE-3> needle (2) (for preauricular and submental skin closure)

5-0 Nylon P-3 (PRE-2, P-13) <RE-3> needle (for closure of temporal skin area)

4-0 polydioxanone PS-3 (P-11, PRE-3) [PC-34] <RE-6>‡ (for approximation of platysmal bands)

CV-4 Gore-Tex, PT-17 needle (only to suture an ePTFE sling into place for revision cases)

Other Supplies:

Skin stapler

Laparotomy pads

Earplugs

Two 8-French red rubber catheters (as postauricular drains)

Wall suction, suction tubing, liposuction cannula (for submentoplasty)

10-cc syringe (2), 27-gauge (11/4-inch long) needle (2) with lidocaine 1% and 1:100,000 epinephrine

Dressing:

4  4 gauze, two of which should have a partial curvilinear incision to accommodate the shape of the ear

4 gauze, two of which should have a partial curvilinear incision to accommodate the shape of the ear

4 gauze, two of which should have a partial curvilinear incision to accommodate the shape of the ear

4 gauze, two of which should have a partial curvilinear incision to accommodate the shape of the ear3″ Conforming gauze bandage, or Kling (3)

Cotton padding

Bacitracin ointment in 5-cc syringe

1″ clear tape

Heavy Scissors

After the submental region has been widely undermined, a liposuction cannula can be introduced with the aperture always facing deep, away from the flap (Fig. 5-5B). The aperture of the cannula should be directed away from the flap in order to avoid the development of an irregular skin contour from suctioning the overlying flap. Furthermore, the vascular supply of the flap emanates from its deep surface, and liposuction under the flap may lead to vascular compromise. The liposuction canister pressure should match the ideal setting of 29” Hg before beginning the procedure. The surgeon should ensure that the instrument is evenly passed over the entire expanse of the undermined submental region, with perhaps additional treatment centrally where a greater adipose

deposit may be observed. The authors discourage routine use of open lipectomy only because direct excision alone tends to be limited to the midline of the neck, leading to an uneven cervical contour, or worse yet a “cobra” deformity. Certainly, a cobra deformity may arise after liposuction (like lipectomy) of the neck if it is conducted in an aggressive fashion only in the central cervical compartment. A cobralike deformity may be further accentuated if the anterior platysmal bands are not united after a central lipectomy.13 However, a central lipectomy may be a useful adjunct in select cases. First, a central lipectomy may be conducted to remove discrete adipose pockets that remain in the midline after a broad liposuction has been carried out. Second, a central lipectomy may be required in order to visualize the anterior platysmal bands obscured by exuberant fat deposition. In select cases, a central lipectomy alone is justified (e.g., a patient who exhibits a discrete submental fat pad), but this task should be carried out in a conservative fashion.

deposit may be observed. The authors discourage routine use of open lipectomy only because direct excision alone tends to be limited to the midline of the neck, leading to an uneven cervical contour, or worse yet a “cobra” deformity. Certainly, a cobra deformity may arise after liposuction (like lipectomy) of the neck if it is conducted in an aggressive fashion only in the central cervical compartment. A cobralike deformity may be further accentuated if the anterior platysmal bands are not united after a central lipectomy.13 However, a central lipectomy may be a useful adjunct in select cases. First, a central lipectomy may be conducted to remove discrete adipose pockets that remain in the midline after a broad liposuction has been carried out. Second, a central lipectomy may be required in order to visualize the anterior platysmal bands obscured by exuberant fat deposition. In select cases, a central lipectomy alone is justified (e.g., a patient who exhibits a discrete submental fat pad), but this task should be carried out in a conservative fashion.

The authors would like to stress a few more remarkable operative considerations concerning liposuction technique. Because the submental incision has already been made and the submental or cervical region undermined before liposuction is begun, it should be noted that “open” versus “closed” liposuction is a superfluous technical distinction. The liposuction aperture is in direct apposition to the adipose bed, thereby forming a sealed, or closed, environment despite the open nature of the wound at the time of liposuction. Recent reports have suggested that other liposuction techniques (e.g., tumescent, liposhaving, ultrasound assisted), may be superior to traditional liposuction. Tumescent technique, which has been applied with success for body liposuction, is less than ideal for the cervico-facial region because the distortion

engendered renders assessment difficult and the persistent edema that arises an unwarranted drawback. The risk of third-space volume shifts further compounds the problem with the tumescent method. Although safety with the liposhaver has been documented in a multi-institutional review,14 the hazard of higher seroma and hematoma rate has not been disproved entirely. The ultrasound method suffers from the attendant risk of increased thermal injury (if internally applied) and neural and cutaneous flap injury. These adverse outcomes are not definitively established because no controlled studies exist, but they remain of concern nevertheless. In all surgical endeavors, the authors advocate that the surgeon strive to undertake the procedure with the most straightforward, yet safest, technique without the crutch of unneeded gadgetry, which may in fact encumber the surgeon and unnecessarily add to overhead cost and intraoperative labor.

engendered renders assessment difficult and the persistent edema that arises an unwarranted drawback. The risk of third-space volume shifts further compounds the problem with the tumescent method. Although safety with the liposhaver has been documented in a multi-institutional review,14 the hazard of higher seroma and hematoma rate has not been disproved entirely. The ultrasound method suffers from the attendant risk of increased thermal injury (if internally applied) and neural and cutaneous flap injury. These adverse outcomes are not definitively established because no controlled studies exist, but they remain of concern nevertheless. In all surgical endeavors, the authors advocate that the surgeon strive to undertake the procedure with the most straightforward, yet safest, technique without the crutch of unneeded gadgetry, which may in fact encumber the surgeon and unnecessarily add to overhead cost and intraoperative labor.

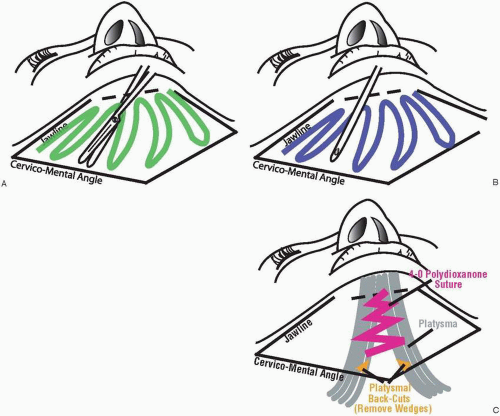

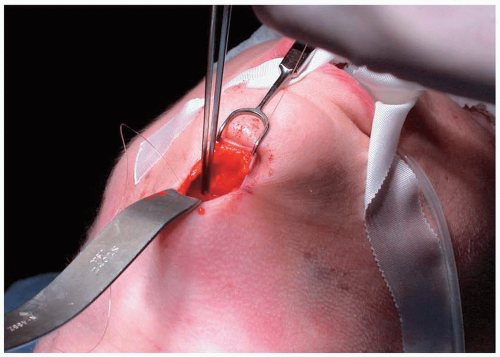

The platysmaplasty may be undertaken after the liposuction has exposed the anterior platysmal border (Fig. 5-6). With headlight illumination and a Converse retractor, the surgeon should properly visualize the anterior terminal fibers of the platysma. If the platysma appears obscured by a wealth of overlying adipose, the surgeon can perform a selective lipectomy with scissor dissection or with the liposuction cannula, as mentioned. The surgeon may elect to resect a narrow strip along the anterior border of the platysma to promote better adherence. Although the efficacy of this step has not been rigorously validated, the authors routinely undertake it unless the platysma is determined to be minimally redundant and the consequent tension of closure would be too great if additional platysmal resection is performed. If the platysmal borders appear widely separated, which would preclude a relaxed closure, then sufficient undermining is carried out to facilitate closure. However, significant subplatysmal dissection increases both the likelihood of poorly controlled and visualized hemorrhage and the risk to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve. Before the platysma may be approximated, the inferior extent of the platysmal closure should be identified (the cervico-mental angle, typically located at the thyroid notch). Small (1- to 2-cm) back cuts with Metzenbaum scissors into each side of the platysma at this level are executed for two reasons: (a) Tension of the closure may effectively be reduced; and (b) the neck profile appears more natural with a graduated break at the cervico-mental angle. The reader is reminded that any platysmal dissection, resection, or transection will lead to some hemorrhage, which should be managed with bipolar cautery at the time the bleeding is encountered. If several areas of hemorrhage are allowed to propagate unabated before electrocautery control, the surgeon will encounter the dubious task of extinguishing these bleeding sites under limited visualization in the confined cervical space illuminated only by headlight. After the platysmal borders have been properly exposed and dissected, the task is then to approximate the anterior free edges with 4-0 polydioxanone (PDS, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ; Maxon, US Surgical/Davis & Geck, Norwalk, CT), or

equivalent, suture in a running, nonlocking fashion. The suture should not be tied very tightly to avoid the complication of a bunched appearance in this area after resolution of edema. To reiterate, the suture should be started approximately at the thyroid notch, or cervico-mental angle, immediately superior to the back cuts that were executed in that region. If a chin implant is not planned, then the submental skin incision is closed with a 6-0 running, locking polypropylene suture alone without the deeper 4-0 polydioxanone subcutaneous retention suture.

equivalent, suture in a running, nonlocking fashion. The suture should not be tied very tightly to avoid the complication of a bunched appearance in this area after resolution of edema. To reiterate, the suture should be started approximately at the thyroid notch, or cervico-mental angle, immediately superior to the back cuts that were executed in that region. If a chin implant is not planned, then the submental skin incision is closed with a 6-0 running, locking polypropylene suture alone without the deeper 4-0 polydioxanone subcutaneous retention suture.

As mentioned, chin augmentation should be carried out after submentoplasty and prior to rhytidectomy. The intended objective for mentoplasty should be kept in mind when deciding on the type of implant to be used. If a hypoplastic mentum requires projection, then a standard implant that is thicker in the middle should be employed. However, if the labiomandibular fold, or prejowl region, requires correction, then a longer implant that extends over the jowl with less central projection should be implemented. An ePTFE or silicone implant can be shaved in the central aspect in order to achieve this desired profile for the prejowl implant, whereas a proper Mersilene mesh implant (Ethicon) may be fashioned with a longer base segment and fewer shorter central segments (vide infra). Although many types of implants have been used successfully for augmentation mentoplasty, the authors have relied on either ePTFE or Mersilene mesh as the two major methods for alloplastic insertion. Both materials offer long-term stability, low morbidity, and a natural appearance. Decision as to which implant to employ is a matter of surgical preference. Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene exhibits the favorable qualities of good biocompatibility, especially in the chin region, ease of insertion and removal, and limited postoperative edema. Mersilene mesh is also very well tolerated, costs considerably less than ePTFE, and may be deemed more versatile as the surgeon can create different sizes of the implant at the time of surgery. However, Mersilene mesh requires additional preparatory time for creation of the implant both preoperatively and intraoperatively (vide infra), is more difficult to insert and remove, and shows more exuberant postoperative edema that resolves over a 1-to 2-week period. Because of these reasons, the authors have shifted away from Mersilene somewhat despite the added expense of ePTFE.

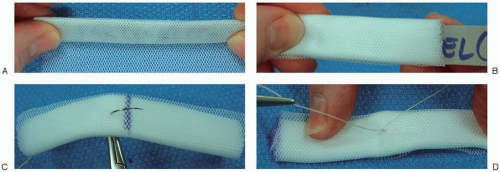

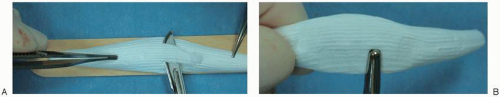

If an ePTFE, or silicone, implant is used, then no preliminary work need be done during the preoperative phase. On the other hand, a Mersilene mesh sheet must be rolled and sutured into precise, prescribed shapes before use. Dr. Perkin’s article provides an excellent defense and review of technique for Mersilene mesh chin augmentation, and the reader is referred there for more details about the background, rationale, safety, and surgical implementation.15 However, this book provides a summary of the major technical points in fabrication of a Mersilene mesh implant with some important modifications of the technique that have worked well for the senior author (Figs. 5-7 and 5-8). All the implants are derived from a single 30-  30-cm sheet of Mersilene mesh. A 10-

30-cm sheet of Mersilene mesh. A 10-  1-cm cardboard template is used to guide construction of the Mersilene-mesh implant: The sheet is rolled over the cardboard template nine times in order to obtain an implant that is 10 layers thick. The cardboard template is then removed from one end of the roll, and the roll is suture fixated together using a 4-0 polydioxanone suture. A smaller-size implant is created that measures 5-

1-cm cardboard template is used to guide construction of the Mersilene-mesh implant: The sheet is rolled over the cardboard template nine times in order to obtain an implant that is 10 layers thick. The cardboard template is then removed from one end of the roll, and the roll is suture fixated together using a 4-0 polydioxanone suture. A smaller-size implant is created that measures 5-  1-cm in dimensions using another cardboard template in the same fashion as in the preceding. The smaller 5-

1-cm in dimensions using another cardboard template in the same fashion as in the preceding. The smaller 5-  1-cm segment is suture fixated to the anterior, central aspect of the larger implant (10

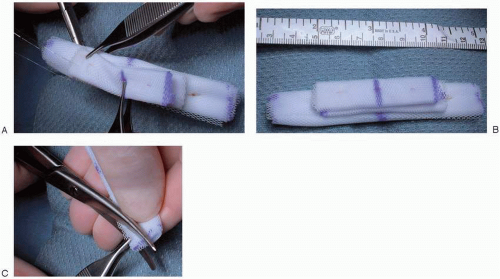

1-cm segment is suture fixated to the anterior, central aspect of the larger implant (10  1 cm) during surgery as needed. Before surgery, all of these individual rolls are packaged and sterilized for intraoperative use. During surgery, the size of augmentation is determined, and the number of tiers that are required to achieve proper chin projection is assessed. At the time of surgery, the segments are sutured together as a stack to achieve the desired height (Figs. 5-7 and 5-8) and the edges are tapered for ease of insertion (Fig. 5-8C). Generally speaking, a medium-sized

1 cm) during surgery as needed. Before surgery, all of these individual rolls are packaged and sterilized for intraoperative use. During surgery, the size of augmentation is determined, and the number of tiers that are required to achieve proper chin projection is assessed. At the time of surgery, the segments are sutured together as a stack to achieve the desired height (Figs. 5-7 and 5-8) and the edges are tapered for ease of insertion (Fig. 5-8C). Generally speaking, a medium-sized

implant that approximates the size of a medium-sized extended ePTFE chin implant requires one 5- 1-cm implant sutured atop a 10-

1-cm implant sutured atop a 10-  1-cm base segment. This configuration constitutes the most common clinical scenario. A larger implant can be made using two 5-

1-cm base segment. This configuration constitutes the most common clinical scenario. A larger implant can be made using two 5-  1-cm segments on top of a single 10-

1-cm segments on top of a single 10-  1-cm segment. However, this amount of augmentation is rarely indicated. Conversely, a smaller amount of augmentation can be achieved with a single 10-

1-cm segment. However, this amount of augmentation is rarely indicated. Conversely, a smaller amount of augmentation can be achieved with a single 10-  1-cm implant. Two 10-

1-cm implant. Two 10-  1-cm implants may be sutured together for increased lateral augmentation in patients with a very pointed chin. Again, this indication is infrequent. Further, insertion of two 10-

1-cm implants may be sutured together for increased lateral augmentation in patients with a very pointed chin. Again, this indication is infrequent. Further, insertion of two 10-  1-cm implants into the lateral, subperiosteal pockets may be quite difficult.

1-cm implants into the lateral, subperiosteal pockets may be quite difficult.

30-cm sheet of Mersilene mesh. A 10-

30-cm sheet of Mersilene mesh. A 10-  1-cm cardboard template is used to guide construction of the Mersilene-mesh implant: The sheet is rolled over the cardboard template nine times in order to obtain an implant that is 10 layers thick. The cardboard template is then removed from one end of the roll, and the roll is suture fixated together using a 4-0 polydioxanone suture. A smaller-size implant is created that measures 5-

1-cm cardboard template is used to guide construction of the Mersilene-mesh implant: The sheet is rolled over the cardboard template nine times in order to obtain an implant that is 10 layers thick. The cardboard template is then removed from one end of the roll, and the roll is suture fixated together using a 4-0 polydioxanone suture. A smaller-size implant is created that measures 5-  1-cm in dimensions using another cardboard template in the same fashion as in the preceding. The smaller 5-

1-cm in dimensions using another cardboard template in the same fashion as in the preceding. The smaller 5-  1-cm segment is suture fixated to the anterior, central aspect of the larger implant (10

1-cm segment is suture fixated to the anterior, central aspect of the larger implant (10  1 cm) during surgery as needed. Before surgery, all of these individual rolls are packaged and sterilized for intraoperative use. During surgery, the size of augmentation is determined, and the number of tiers that are required to achieve proper chin projection is assessed. At the time of surgery, the segments are sutured together as a stack to achieve the desired height (Figs. 5-7 and 5-8) and the edges are tapered for ease of insertion (Fig. 5-8C). Generally speaking, a medium-sized

1 cm) during surgery as needed. Before surgery, all of these individual rolls are packaged and sterilized for intraoperative use. During surgery, the size of augmentation is determined, and the number of tiers that are required to achieve proper chin projection is assessed. At the time of surgery, the segments are sutured together as a stack to achieve the desired height (Figs. 5-7 and 5-8) and the edges are tapered for ease of insertion (Fig. 5-8C). Generally speaking, a medium-sized implant that approximates the size of a medium-sized extended ePTFE chin implant requires one 5-

1-cm implant sutured atop a 10-

1-cm implant sutured atop a 10-  1-cm base segment. This configuration constitutes the most common clinical scenario. A larger implant can be made using two 5-

1-cm base segment. This configuration constitutes the most common clinical scenario. A larger implant can be made using two 5-  1-cm segments on top of a single 10-

1-cm segments on top of a single 10-  1-cm segment. However, this amount of augmentation is rarely indicated. Conversely, a smaller amount of augmentation can be achieved with a single 10-

1-cm segment. However, this amount of augmentation is rarely indicated. Conversely, a smaller amount of augmentation can be achieved with a single 10-  1-cm implant. Two 10-

1-cm implant. Two 10-  1-cm implants may be sutured together for increased lateral augmentation in patients with a very pointed chin. Again, this indication is infrequent. Further, insertion of two 10-

1-cm implants may be sutured together for increased lateral augmentation in patients with a very pointed chin. Again, this indication is infrequent. Further, insertion of two 10-  1-cm implants into the lateral, subperiosteal pockets may be quite difficult.

1-cm implants into the lateral, subperiosteal pockets may be quite difficult.As far as the ePTFE implant is concerned, the implant is typically manufactured in three extended sizes: small, medium, and large. In the great majority of cases (approximately

80%), a medium-sized implant is sufficient for adequate projection or to soften the prejowl fullness, whereas the remaining 20% of the time is equally divided between use of a small and large implant. The small implant is really designed for the minority of patients who only want very subtle augmentation. Because most patients who elect to undergo chin augmentation are willing to incur the extra expense, they typically desire a little more noticeable augmentation than can be afforded by a small-sized implant. In addition, the medium-sized implant is more versatile because it can be sculpted to be smaller in size: Carving the central aspect down with a No. 10 blade followed by crushing the implant with a needle holder along the central aspect can reduce the projection of the implant (Fig. 5-9A,B). Crushing the implant after carving also helps to soften the transition along the transected edge. With the large implant, the reader is reminded to assess the patient’s occlusion before electing to place this implant. Often, the patient who has a significant recession of the chin exhibits concomitant occlusal disharmony, usually a class II occlusion, or “overbite.” Obviously, placement of a large implant will do nothing for the occlusal problem, and the patient should be counseled about that fact.

80%), a medium-sized implant is sufficient for adequate projection or to soften the prejowl fullness, whereas the remaining 20% of the time is equally divided between use of a small and large implant. The small implant is really designed for the minority of patients who only want very subtle augmentation. Because most patients who elect to undergo chin augmentation are willing to incur the extra expense, they typically desire a little more noticeable augmentation than can be afforded by a small-sized implant. In addition, the medium-sized implant is more versatile because it can be sculpted to be smaller in size: Carving the central aspect down with a No. 10 blade followed by crushing the implant with a needle holder along the central aspect can reduce the projection of the implant (Fig. 5-9A,B). Crushing the implant after carving also helps to soften the transition along the transected edge. With the large implant, the reader is reminded to assess the patient’s occlusion before electing to place this implant. Often, the patient who has a significant recession of the chin exhibits concomitant occlusal disharmony, usually a class II occlusion, or “overbite.” Obviously, placement of a large implant will do nothing for the occlusal problem, and the patient should be counseled about that fact.

FIGURE 5-9. ePTFE Chin Implant Preparation (Intraoperative Sequence). A: A larger expanded polytetrafluoroethylene implant can be reduced in profile by shaving down the central prominence with a No. 10 blade. B: A needle holder can be used to compress the implant to assume an even flatter profile. Gently crushing the implant after shaving down the central aspect permits a smoother, less abrupt, transition at the interface of the cut edge. In addition, crushing the implant permits reducing the profile further without compromising the integrity of the implant that would occur if it were overly thinned by resection alone.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|