The goal of lower eyelid blepharoplasty is to rejuvenate the lower lid while maintaining a natural, unoperated appearance. Successful lower eyelid blepharoplasty depends on knowledge of the anatomy and surgical techniques, accurate preoperative analysis, and attention to detail. Common issues of the lower eyelid such as malar descent, tear trough deformity, pseudoherniated fat, lid laxity, and skin texture changes as well as dermatochalasis and festoons must be recognized. Specific techniques to address these include transcutaneous and transconjunctival approaches, fat excision, fat transposition, orbicularis suspension, lateral canthal tightening, malar suspension, and skin excision/resurfacing.

Key points

- •

Incisions and flap elevation should be performed in a manner to prevent postoperative lid malposition taking care to preserve the pretarsal orbicularis muscle sling.

- •

Fat excision should be conservative to avoid skeletonizing the eye. Volume can be restored to the lid/cheek by fat transposition, fat autografts, and injectable filler materials.

- •

Orbicularis, suborbicularis oculi fat, and other lateral suspension techniques can be used to correct aging changes in the lateral lid/cheek junction.

- •

Conservative skin excision via subciliary approach can correct lower lid dermatochalasis.

- •

Aging changes associated with the medial lower lid require different approaches than the lateral lower lid.

Introduction

Lower eyelid blepharoplasty involves a complex set of maneuvers to rejuvenate the lower lid/cheek complex. The choice of which techniques to use depends on an accurate analysis of each patient’s presenting problems. Ultimate success with the chosen techniques for a specific patient relies on knowledge of the relevant anatomy and meticulous execution of the surgical plan.

As we age, the brow descends and the distance from the brow/lid junction to the upper lid margin decreases, causing the eye to close in and present a tired and angry appearance. In the midface, the cheek descends and the distance from the lower lid margin to the lid/cheek junction increases resulting in a loss of the smooth transition from lid to cheek and isolation of these facial subunits. In lower lid blepharoplasty, the surgeon is attempting to reverse aging and gravitational changes in the lid/cheek complex with a goal to shorten that distance and suspend tissues, whereas in the upper lid the goal is to lengthen the distance from the brow to the lid margin, which decreases with time. Just as in upper eye rejuvenation the brow must be addressed, so in lower eye rejuvenation the cheek/malar area must be addressed. In both, volume restoration is critical to the overall rejuvenation plan. The skin texture changes that occur with age in the lower lid present an additional issue and these must be addressed as well. Smooth skin is as important as other factors in determining the perception of youthfulness and beauty. Although this article focuses on lower eyelid rejuvenation and it is convenient to divide it in this manner, the entire periorbital area including brow and midface must be viewed and addressed as a whole.

Introduction

Lower eyelid blepharoplasty involves a complex set of maneuvers to rejuvenate the lower lid/cheek complex. The choice of which techniques to use depends on an accurate analysis of each patient’s presenting problems. Ultimate success with the chosen techniques for a specific patient relies on knowledge of the relevant anatomy and meticulous execution of the surgical plan.

As we age, the brow descends and the distance from the brow/lid junction to the upper lid margin decreases, causing the eye to close in and present a tired and angry appearance. In the midface, the cheek descends and the distance from the lower lid margin to the lid/cheek junction increases resulting in a loss of the smooth transition from lid to cheek and isolation of these facial subunits. In lower lid blepharoplasty, the surgeon is attempting to reverse aging and gravitational changes in the lid/cheek complex with a goal to shorten that distance and suspend tissues, whereas in the upper lid the goal is to lengthen the distance from the brow to the lid margin, which decreases with time. Just as in upper eye rejuvenation the brow must be addressed, so in lower eye rejuvenation the cheek/malar area must be addressed. In both, volume restoration is critical to the overall rejuvenation plan. The skin texture changes that occur with age in the lower lid present an additional issue and these must be addressed as well. Smooth skin is as important as other factors in determining the perception of youthfulness and beauty. Although this article focuses on lower eyelid rejuvenation and it is convenient to divide it in this manner, the entire periorbital area including brow and midface must be viewed and addressed as a whole.

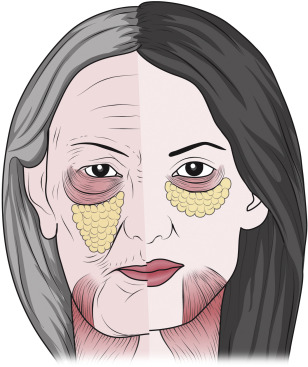

Aging changes of the lower lid and cheek

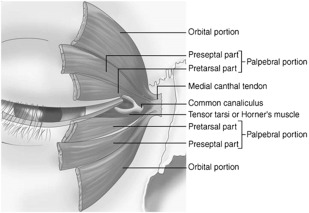

In youth, there is a smooth transition from the lid to the cheek with a full malar mound and a single convexity. There is no demarcation between the midface and lower lids and the skin is smooth. As we age, the changes that occur combine to create a vertically elongated lower eyelid, ptotic malar/cheek complex, a lax lower eyelid and protrusion of orbital fat. Each of these changes can be attributed to specific changes in the supporting ligaments and tissues of the face and eyes ( Fig. 1 ). The orbicularis oculi muscle (OOM) is composed of a palpebral portion, which consists of pretarsal and preseptal components and an orbital component. The pretarsal component lies just anterior to the tarsus, which in the lower lid measures approximately 4 mm. The preseptal component begins at the inferior border of the tarsus and transitions to the orbital component at the arcus marginalis or orbital rim ( Fig. 2 ). Medially, the tear trough or nasojugal groove is formed owing to the attachment of the orbicularis to the orbital bone just below the orbital rim without an intervening ligamentous structure ( Fig. 3 ). Laterally, the orbicularis is attached to the bone via the orbital retaining ligament.

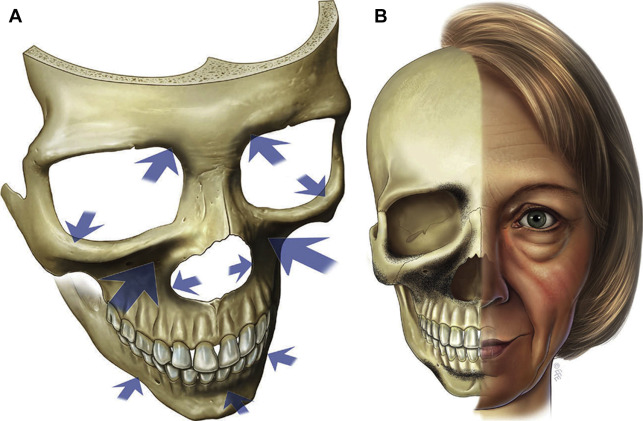

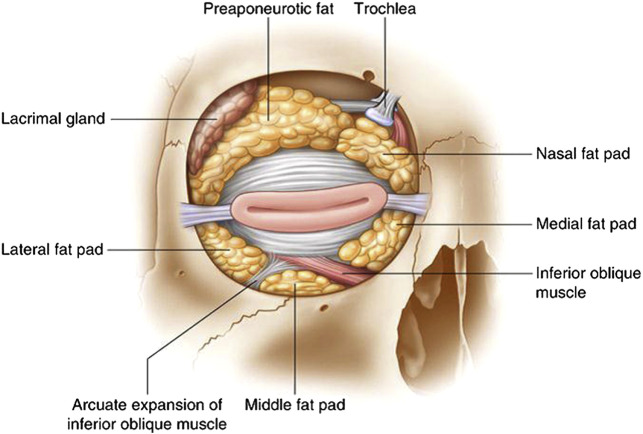

By measuring the lid length in individuals at every decade from their 20s to their 90s, Fezza and colleagues have shown that there is a steady linear increase in lid length as measured from the lid margin to the orbital rim. The greatest change was noted in patients in their 40s. Bone loss in the periorbital and malar regions contributes to the overall volume loss associated with aging and loss of projection of the orbital rim ( Fig. 4 ). The orbital septum weakens, orbicularis atrophies, and the skin becomes lax with time and allows orbital fat to pseudoherniate outside the bounds of the orbital rim. There is also evidence that the globe becomes downwardly displaced owing to loss of support exerting a downward pressure on the orbital fat and outward pressure on the orbital septum. This formed the basis of the approach to return the fat to the orbit by securing the capsulopalpebral fascia to the orbital rim periosteum. The medial and central fat pads are divided by the inferior oblique muscle and accentuate the tear trough or nasojugal groove. The lateral fat pad is responsible for the superior convexity and is separated from the central fat pad by the arcuate expansion ( Fig. 5 ). It has been shown that the lower intraorbital fat is actually a continuous body of fat, but it is helpful to visualize this as 3 compartments because this is how it is manipulated surgically. It was posited by Yousif and colleagues that the presence of the inferior oblique muscle medially and the arcuate expansion laterally divide the fat pads by exerting pressure on them as the herniate outward and engulf these structures. In their discussion of the anatomy of the transconjuctival approach, they also describe the presence of the suborbicularis oculi fat (SOOF). With age, the lateral canthal tendon relaxes as well and the lower lid lengthens and the lower lid tarsal support is diminished, thus predisposing to a postoperative lid malposition if unrecognized.

Approaches to lower lid rejuvenation

The earliest blepharoplasties were performed via a transcutaneous approach using either a skin or skin muscle flap through a subciliary incision. In doing so, the pretarsal OOM was violated, causing a loss of support to the tarsus and rounding at the lateral canthus with increased lateral scleral show. The next phase of lower lid rejuvenation involved the excision of orbital fat through a transconjuctival incision, which was described in 1973 by Tessier. In a large study of 400 incisions, this approach has been shown to be safe and effective with few complications. In a comparison of the transconjunctival approach to the transcutaneous approach, there was a 3% rate of permanent scleral show associated with the transconjuctival approach and a 28% rate of permanent scleral show with the transcutaneous approach. Initially, the transconjunctival approach was reserved typically for the younger patient with minimal dermatochalasis and texture change; however, it has gained wide acceptance in periorbital rejuvenation.

Surgeons should be cautious with overresection of the fat because this can produce a hollowed eye that is less youthful and more skeletonized. Moreover, this effect may not manifest itself in the early postoperative period. Manson and colleagues have shown that the globe is moved posteriorly by 2 mm and inferiorly by 1 mm for every 2.5 mL of fat removed. Currently, there is an emphasis on fat conservation with transposition for restoring contour medially and very conservative fat excision in the lateral compartment.

Excess skin is excised conservatively via a skin pinch or skin only flap that is elevated via subciliary incision. This is accompanied usually by a lateral suspension procedure, such as orbicularis suspension. Skin texture changes can also be improved with resurfacing such as laser or chemical peel.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree