IN THIS CHAPTER

- •

Introduction 47

- •

Patient selection 48

- •

Preoperative history and considerations 48

- •

Operative approach 48

- •

Postoperative Care 52

- •

Conclusion 52

Introduction

Many surgical techniques are currently available for abdominal contouring. Based on the individual characteristic of the patients’ anatomy and their goals, these abdominal contouring procedures include, liposuction, mini abdominoplasty, and full abdominoplasty. According to the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery’s 2004 Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank, during the previous 7 years the number of abdominoplasty procedures performed increased by 344%. In 2006, a survey study of randomly chosen members of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons evaluated the frequency of various abdominal contour techniques and complications. There were 497 respondents, and a total of 20 029 procedures reported. Regarding the types of abdominal contouring procedures performed, 35% (7010) were liposuction of the abdomen, 10% (2003) were limited abdominoplasties, and 55% (11 016) were full abdominoplasties.

The advent of liposuction dramatically altered the field of body contouring surgery and vastly improved our ability to contour the abdomen (see Chapter 3 ). There has been much debate about performing liposuction on an undermined abdominoplasty flap, the use of wetting solutions, and the safety of combining plastic surgery procedures with abdominal contouring surgery. Since the first publication on lipoplasty by Illouz in 1980, liposuction has increasingly been associated with abdominoplasty resections. Initially, liposuction was rarely performed at the same time as classic abdominoplasty, because of the fear of compromising blood supply to the flap, and also of accumulating fluids under the flap, thereby increasing seroma rates. Matarasso’s publication describing the safety areas for lipoplasty in the abdominal region – the epigastric and mesogastric areas – did not recommend lipoplasty at the same time as classic abdominoplasty. Hunstad and Stevens and others have used liposuction in these areas without ischemic consequences.

Because of these concerns, abdominoplasty and liposuction have often been performed together, albeit with a reduced skin resection superior to the mons or by limiting liposuction to the flank and dorsal areas. Unfortunately, these approaches have limitations, either because of inadequate skin resection, leaving residual laxity in the supraumbilical area, or as a result of limited or absent abdominal liposuction, leaving residual excessive central abdominal thickness.

The technique of ‘lipoabdominoplasty’ was described by Saldanha in 2003. This combines liposuction of the entire abdomen and flanks, reduced undermining, complete midline aponeurotic plication, and traditional abdominal skin flap resection. This new approach offers some advantages and may reduce the most common complications of ischemia and seroma seen with classic abdominoplasty. The wide undermining of the abdominal flap in traditional abdominoplasty is believed by some to be a cause of complications. Distal skin ischemia and necrosis can be reduced in lipoabdominoplasty by the limited skin flap undermining and by preserving most of the peri- and supraumbilical perforator vessels to the abdominal skin. The incidence and volume of seromas was also shown to be reduced because of the reduced undermining, and by using space-obliterating ‘quilting sutures’ between the undersurface of the elevated skin and fat and the abdominal wall. The supraumbilical flap undermining (tunnel), however, was made wide enough to allow for myofascial plication to correct rectus diastasis from the xiphoid to the mons. Closure was facilitated with quilting sutures described by Baroudi, and no suction drains are used.

Introduction

Many surgical techniques are currently available for abdominal contouring. Based on the individual characteristic of the patients’ anatomy and their goals, these abdominal contouring procedures include, liposuction, mini abdominoplasty, and full abdominoplasty. According to the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery’s 2004 Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank, during the previous 7 years the number of abdominoplasty procedures performed increased by 344%. In 2006, a survey study of randomly chosen members of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons evaluated the frequency of various abdominal contour techniques and complications. There were 497 respondents, and a total of 20 029 procedures reported. Regarding the types of abdominal contouring procedures performed, 35% (7010) were liposuction of the abdomen, 10% (2003) were limited abdominoplasties, and 55% (11 016) were full abdominoplasties.

The advent of liposuction dramatically altered the field of body contouring surgery and vastly improved our ability to contour the abdomen (see Chapter 3 ). There has been much debate about performing liposuction on an undermined abdominoplasty flap, the use of wetting solutions, and the safety of combining plastic surgery procedures with abdominal contouring surgery. Since the first publication on lipoplasty by Illouz in 1980, liposuction has increasingly been associated with abdominoplasty resections. Initially, liposuction was rarely performed at the same time as classic abdominoplasty, because of the fear of compromising blood supply to the flap, and also of accumulating fluids under the flap, thereby increasing seroma rates. Matarasso’s publication describing the safety areas for lipoplasty in the abdominal region – the epigastric and mesogastric areas – did not recommend lipoplasty at the same time as classic abdominoplasty. Hunstad and Stevens and others have used liposuction in these areas without ischemic consequences.

Because of these concerns, abdominoplasty and liposuction have often been performed together, albeit with a reduced skin resection superior to the mons or by limiting liposuction to the flank and dorsal areas. Unfortunately, these approaches have limitations, either because of inadequate skin resection, leaving residual laxity in the supraumbilical area, or as a result of limited or absent abdominal liposuction, leaving residual excessive central abdominal thickness.

The technique of ‘lipoabdominoplasty’ was described by Saldanha in 2003. This combines liposuction of the entire abdomen and flanks, reduced undermining, complete midline aponeurotic plication, and traditional abdominal skin flap resection. This new approach offers some advantages and may reduce the most common complications of ischemia and seroma seen with classic abdominoplasty. The wide undermining of the abdominal flap in traditional abdominoplasty is believed by some to be a cause of complications. Distal skin ischemia and necrosis can be reduced in lipoabdominoplasty by the limited skin flap undermining and by preserving most of the peri- and supraumbilical perforator vessels to the abdominal skin. The incidence and volume of seromas was also shown to be reduced because of the reduced undermining, and by using space-obliterating ‘quilting sutures’ between the undersurface of the elevated skin and fat and the abdominal wall. The supraumbilical flap undermining (tunnel), however, was made wide enough to allow for myofascial plication to correct rectus diastasis from the xiphoid to the mons. Closure was facilitated with quilting sutures described by Baroudi, and no suction drains are used.

Patient Selection

We select patients for this procedure based on the clinical classification of Bozola: type I, fat deposit, normal musculoaponeurotic layer and no skin excess; type II, mild skin excess, normal musculoaponeurotic layer, fat may or may not be in excess; type III, mild skin excess, laxity of the infraumbilical area of the musculoaponeurotic layer, fat may or may not be present; type IV, mild skin excess, laxity in the whole extension of the musculoaponeurotic layer, fat may or may not be in excess; and type V, large skin excess, laxity of the musculoaponeurotic layer with or without hernias, fat may or may not be in excess.

The procedure of lipoabdominoplasty with traditional abdominal flap resection is indicated for types III–V. Ideal candidates are those with indications for traditional abdominoplasty with rectus diastasis, skin laxity, and significant excess adiposity requiring liposuction, particularly in the supraumbilical area.

Preoperative History and Considerations

The preoperative considerations for lipoabdominoplasty are similar to those for full abdominoplasty (see Chapter 7 ). Because of the more limited undermining and preservation of important perforating vessels, the need for absolute smoking cessation is reduced. Preoperative history and physical examination are performed. A previous history of DVT/PE would require hematologic evaluation and work-up prior to surgery. Existing scars and the presence of any hernia should be evaluated. For a healthy patient taking no medications, basic preoperative laboratory analysis should be considered.

Operative Approach

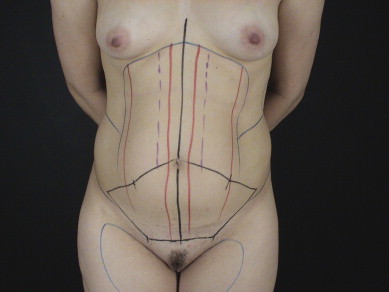

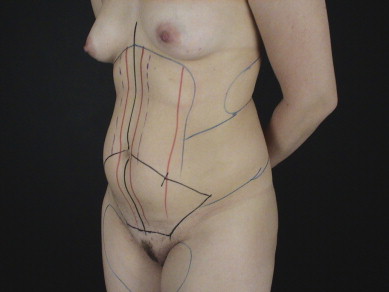

The skin is marked with the patient in the standing position. The midline and the proposed suprapubic incision line are marked. The lower incision line is extended laterally towards the anterior superior iliac spine. Existing scars and natural creases are used to place the incisions. ( Figs 6.1 and 6.2 ). The superior line is marked as a bicycle handlebar incision as described by Baroudi. The areas for liposuction are marked, including all of the upper abdomen to the level of the inframammary crease superiorly and laterally to the flanks ( Figs 6.1 and 6.2 ).

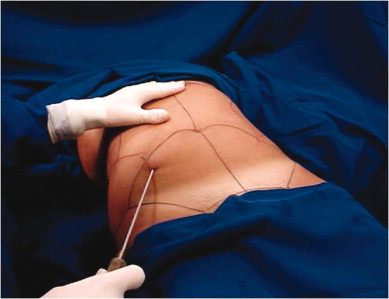

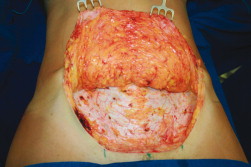

Intermittent compression stockings are worn prior to the beginning of surgery and continued until 6 hours afterwards. Epidural anesthesia is used for the majority of procedures, with some selected cases performed under general anesthesia. Infiltration for liposuction is performed using the superwet technique with an epinephrine concentration of 1:500 000; liposuction is performed with 3.0 and 3.5 mm cannulas, beginning initially in the deep subcutaneous layer and then superficially in the flanks and upper abdomen, except in the area superior to the umbilicus. Liposuction in the central supraumbilical area is performed only in the deep layer ( Fig. 6.3 ). When the liposuction is complete, the lower abdominal flap is undermined using electrocautery up to the umbilicus, the skin around it is incised, and the flap is split from the umbilicus inferiorly ( Figs 6.4 – 6.7 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree